- Biomedical Research (2013) Volume 24, Issue 1

Time of PMSG administration: Effect on progesterone and estradiol concentration in synchronized ewes.

Noor Hashida Hashim1,*, Syafnir2, Meriksa Sembiring21Centre For Foundation Studies in Science, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

2Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Noor Hashida Hashim

Centre For Foundation Studies in Science

University of Malaya

50603 Kuala Lumpur

Malaysia

Accepted Date: October 03 2012

Abstract

The objective of this study was to observe the effect of Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotrophin (PMSG) administration time on progesterone (P4) and estradiol (E2) concentrations in synchronized ewes. The experimental animals used in this study were Cameroon hair sheep and Thai Long Tail wool sheep crossbreds. Controlled Internal Drug Release (CIDR) device was implanted intravaginally to 40 ewes for 11 and 13 days. Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotrophin (PMSG), 200 I.U. was administered at CIDR withdrawal and 24 hours prior to CIDR withdrawal. Blood samples were collected between 3 to 4 day intervals for 6 weeks after CIDR implantation. The P4 and E2 blood plasma concentrations were measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA). Ewes that received PMSG at CIDR withdrawal gave significantly higher P4 and E2 concentrations as compared to ewes that received PMSG at 24 hours prior to CIDR withdrawal in both 11 and 13 days CIDR implantation. In conclusion, PMSG administration at 24 hour prior to or at CIDR withdrawal would affect the concentrations of blood plasma P4 and E2 in synchronized ewes and subsequently would affect the reproductive performance in ewes.

Keywords

Progesterone, Estradiol, CIDR, PMSG, ewes

Introduction

In small ruminants, estrus synchronization was achieved either by extending the cycle with exogenous progesterone or its analog progestagen or reducing the length of the luteal phase of the estrus cycle with prostaglandin (F2α) [1]. These synchronization regimes were orally implanted or intravaginal sponges insertion. These devices would exert negative feedback on Luteinizing Hormone (LH) secretion that inhibited the endocrine events and lead to the maturation of preovulatory follicles and ovulation [2].

The most general synchronization technique in sheep was progestagen intravaginal devices which was implanted for 12 to14 days, followed by administration of equine chorionic gonadotrophin (eCG). This method would synchronize estrus in cyclic ewes or induced and synchronized estrus during the anestrus period in sheep. This method of intravaginal progestagen was the most practical for sheep reproductive management programs, but the fertility rates were highly variable [3]. Titi et al. [4] reported that a combination of progestagen sponge with Gonadotrophin Releasing Hormone (GnRH) administration was effective in estrus synchronization and increased fecundity in small ruminants. The administration of GnRH in estrus synchronization technique could facilitate synchronized ovulation or luteinization of most large dominant follicles and initiated follicular growth [5].

Yu et al. [6] recorded a high correlation between the development of follicles with serum progesterone (P4) and estradiol (E2) concentrations. Previous studies reported that progesterone concentration might affect the follicular size [7]. Estradiol concentration was also reported to have positive correlation with the number of large follicles during the estrus cycle [6].

Therefore, present study was conducted to observe either administration of PMSG 24 hours prior to CIDR sponge withdrawal or administration of PMSG at CIDR sponge withdrawal would result in better progesterone and estradiol concentrations. Also to test the efficiency of combined CIDR sponge implantation and time of PMSG administration to potentially facilitates fix timed artificial insemination (FTAI).

Materials and Methods

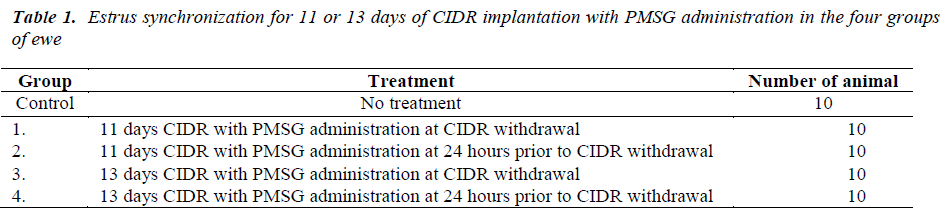

Cameroon hair sheep and Thai Long Tail wool sheep crossbreds were synchronized with CIDR device. This device was implanted intravaginally into 40 ewes for 11 and 13 days. Each treatment group was then received intramuscular injection of 200I.U. PMSG. Ewes were randomly assigned into 5 groups with 10 ewes for each group; G1 (control), G2 (CIDR implantation for 11 days with PMSG administration at CIDR withdrawal), G3 (CIDR implantation for 11 days with PMSG administration at 24 hours prior to CIDR withdrawal), G4 (CIDR implantation for 13 days with PMSG administration at CIDR withdrawal) and G5 (CIDR implantation for 13 days with PMSG administration at 24 hours prior to CIDR withdrawal) (Table 1).

After the CIDR implantation (day 0), a series of blood samples was collected between 3 to 4 day intervals for 6 weeks. Blood samples were obtained from a jugular vein using vacutainer vials and centrifuged immediately after collection at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4oC. The blood plasma was then stored at -20oC until assayed. The plasma progesterone (P4) concentration was measured by radioimmunoassay (RIA) (Coat-A-Count; Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, USA) with intra- and interassay coefficients of variation of 9.5 and 8.3%, respectively. The plasma estradiol (E2) concentration was measured by RIA (Coat-A-Count; Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, USA) with intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation of 5.8 and 5.4 %, respectively.

Statistical analyses on the concentration of estradiol and progesterone were performed on a microcomputer using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) programme (version 20.0). Data were analyzed through analysis of variance (ANOVA) with significant difference level of P<0.05.

Results

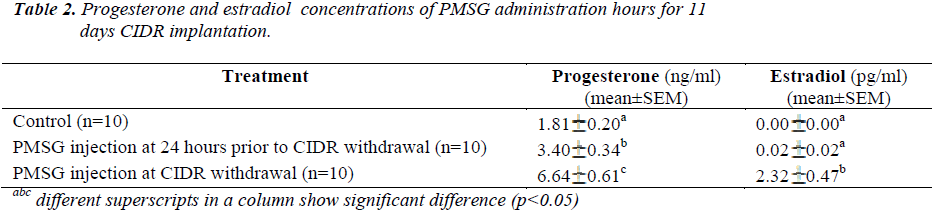

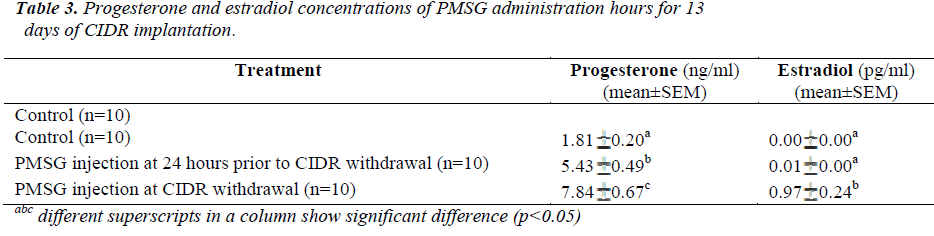

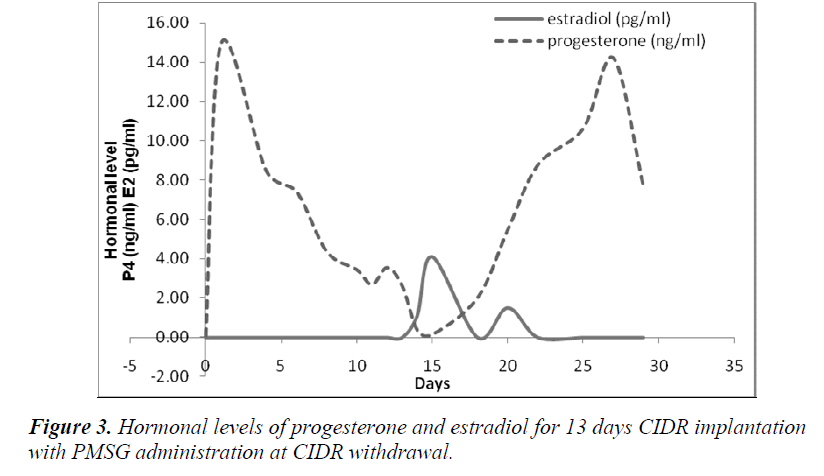

Present results showed that administration of PMSG at CIDR withdrawal for 11 days of CIDR implantation (G1G2) gave significantly higher P4 and E2 concentrations (6.64±0.61 ng/ml and 2.32±0.47 pg/ml, respectively) as compared to that observed in the control G1 and G2 G3 groups (p<0.05) (Table 2). Similarly, for 13 days of CIDR implantation, administration of PMSG at CIDR withdrawal (G3 G4) also gave significantly higher concentration of P4 and E2 (7.84 0.67 ng/ml and 0.97 0.24 pg/ml, respectively) as compared to the other two groups (Control G1 and G4 G5) (p<0.05) (Table 3).

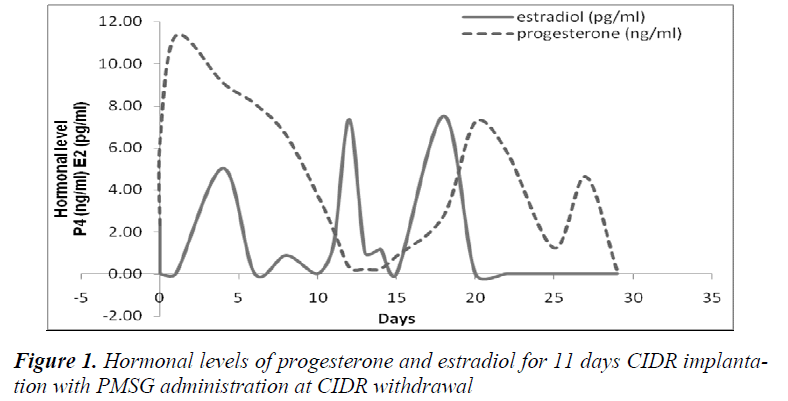

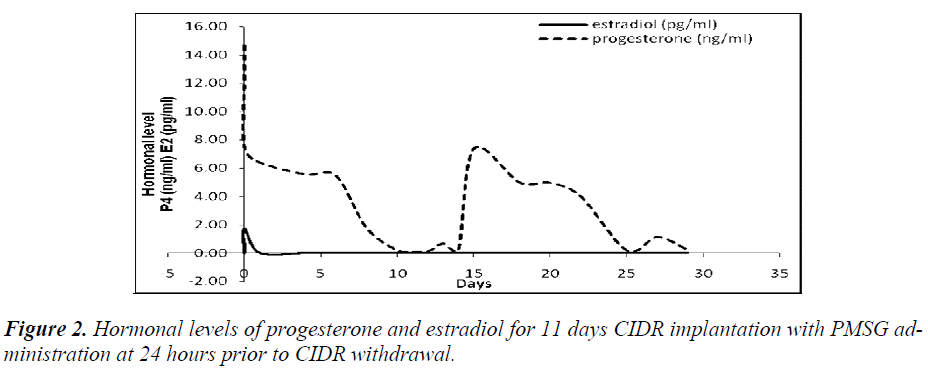

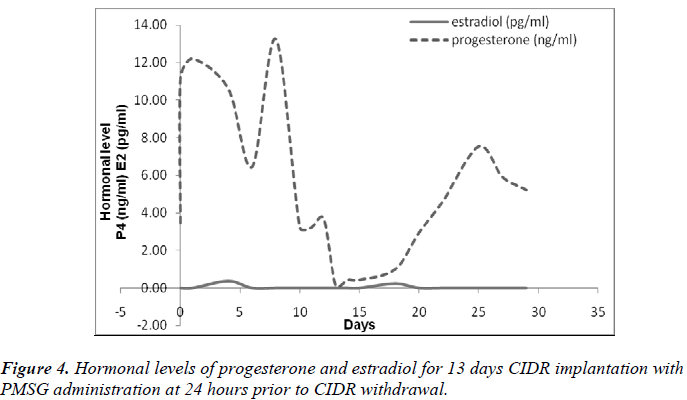

It was also observed that administration of PMSG in G2 G3 and G4 G5 (Figures 2 and 4, respectively) gave no response to E2 concentration which was contradicted to that observed in G1 G2 and G3 G4 (Figures 1 and 3, respectively).

It was observed that P4 started to increase at 72 hours after CIDR withdrawal in G1 G2 (Figure 1) and at 24 hours in G2 G3 (Figure 2). Progesterone (P4) started to increase at 48 hours after CIDR withdrawal in G3 G4 (Figure 3). However, in G4 G5 (Figure 4), P4 was observed to increase at CIDR withdrawal (0 hour). In contrary, E2 was observed to reach maximum level at 24 hours (Figure 1) and 48 hours (Figure 3) after CIDR withdrawal.

Discussion

Intravaginal devices with progesterone or progestagens are the most commonly used procedures which can be combined with gonadotrophin hormone to increase ovulatory efficiency and ovulation rate. Present study showed significantly higher concentrations of P4 and E2 in both 11 and 13 CIDR implantation for PMSG administration at CIDR withdrawal as compared to PMSG administration at 24 hours prior to CIDR withdrawal.

PMSG-intervet which was used in the present study contained 5000 I.U. serum gonadotrophin when reconstituted with solvent would give a solution containing 200 I.U. PMSG per ml. Pregnant Mare Serum Gonadotrophin (PMSG) can be substituted for both LH and Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) of the anterior pituitary gland which stimulate development of the ovarian follicle. Probably, administration of PMSG at 24 hours prior to CIDR withdrawal would block the ovarian steroidogenesis due to the presence of progesterone in the serum. High P4 concentration would inhibit FSH thus, prevent development of ovarian follicles, ovulation and estrus. Therefore, administration of PMSG at 24 hours prior to CIDR withdrawal would not give any response to E2 concentration.

It has been previously showed that eCG injection at 24 hours prior to the intravaginal sponge removal or at the time of removal had a desirable effect on lambing rate, multiple birth and fecundity rates of treated ewes compared to those received treatment at 24 hours after intravaginal sponge removal [8]. It has also been shown that a single dose of GnRH injection at 24 hours after CIDR removal could rise the number of embryos in multiple ovulation and embryo transfer (MOET) protocols [9,10]

In contrary, Mohammad Ali Sirjani et al. [11] reported that the lambing rate and litter size increased to ≥150% in ewes in which GnRH was treated at 48 hours after CIDR removal. Gonadotrophin Releasing Hormone (GnRH) injection may increase the number of ovulations and consequently, it leads to increase the lambing rate, litter size and multiple birth rates in synchronized ewes. However, there are the discrepancy results, which reported that GnRH administration at 36–48 h after intravaginal sponge removal did not increase the fertility and lambing rate in ewes [12,13]. It was reported that GnRH administration might induce a premature ovulation or less functional corpora lutea and with a subsequent reduced fertility [14]. However, Karaca et al. [15] found exogenous GnRH administration immediately prior to a short-term progestagen treatment (7 days) was able to increase the fertility rate, multiple births and litter size.

All treatment groups showed abrupt rise in P4 levels after CIDR implantation and sharp decline to basal values prior to CIDR withdrawal. Hussein and Ababneh [16] reported that this phenomenon would reset the hypothalamic- pituitary-ovarian to regress persistent follicles and recruit new healthy follicles. The E2 profiles recorded in the present work were characterized by 2 peaks. Such an increase in the E2 concentration during the early luteal phase has also been shown in a previous study [17]. In addition to the preovulatory peak in E2 concentration at the onset of estrus, a second peak of lower magnitude occurred 4–6 days later during the bovine and ovine ovulatory cycle [18,19]. Estradiol (E2) is considered as a good marker of follicular quality [20]. The number of large follicles and E2 concentrations were positively correlated during the estrus cycle.

In our opinion, time of PMSG administration would affect concentrations of P4 and E2 blood plasma and thus affect reproductive performance in ewes. More research should be carried out in this area to provide a better understanding in the endocrine aspects of reproduction in ewes. It is hoped that the results obtained from this current study will provide better understanding of the mechanism of hormonal control in ewes reproduction, thus enabling us to overcome many problems related to the abnormal reproductive status in sheep. Also, it may increase the success rate of animals undergoing advanced reproductive technology such as artificial insemination (AI), in vitro fertilization (IVF), embryo transfer (ET) and cloning.

Acknowledgement

The present study was supported by Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS), Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI). Project number FP008/2009.

Competing financial interest

The Authors declare that they do not have any competing financial interest.

References

- Jainudeen MR, Wahid H, Hafez ESE. Ovulation induction, embryo production and transfer. 7th. Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (Baltimore), New York 2000; 405-430.

- Hansel W, Convey EM. Physiology of estrus cycle. J. Anim Sci (suppl) 1983; 57: 104-412.

- Martemucci G, D’Alessandro AG. Strategies for improving reproductive efficiency in sheep. Pharmacological synchronization of estrus and ovulation. Agr Res 1999; 183: 3-18.

- Titi HH, Kridli RT, Alnimer MA. Estrus synchronization in sheep and goat using combinations of GnRH, progestagen and prostaglandin F2alpha. Reprod Domest Anim 2010; 45: 594-599.

- Twagiramungu H, Gullbault LA, Dufour JJ. Synchronization of ovarian follicular waves with a gonadotrophin- releasing hormone agonist to increase the precision of estrus in cattle: a review. J. Anim Sci 1995; 73: 3141-3151.

- Yu YS, Luo MJ, Han ZB, Li W, Sui HS, Tan JH. Serum and follicular fluid steroid levels as related to follicular development and granulose cell apoptosis during the estrus cycle of goats. Small Rumin Res 2005; 57: 57-65.

- Tenorio Filho F, Santos MHB, Carrazzoni PG, Paulo- Lopez FF, Neves JP, Bartolomeu CC, Lima PF, Oliveira MAI. Follicular dynamics in Anglo-Nubian goats using transrectal aqnd transvaginal ultrasound. Small Rumin Res 2007; 72: 51-56.

- Koyuncu M, Ozis Alticekic S. Effects of progestagen and PMSG on estrus synchronization and fertility in Kivircik ewes during natural breeding season. Asian- Aust J Anim Sci 2010; 23: 308-311.

- Menchaca A, Vilarino M, Pinczak A, Kmaid S, Saldana JM. Progesterone treatment FSH plus eCG, GnRH administration and day 0 protocol for MOET programs in sheep. Theriogenology 2009; 72: 477-483.

- Pawson AJ, McNeilly AS. The pituitary effects of GnRH. Anim Reprod Sci 2005; 88: 75-79.

- Mohammad Ali Sirjani, Hamid Kohram, Mohammad Hossein Shahir. Effects of eCG injection combined with FSH and GnRH treatment on the lambing rate in synchronized Afshari ewes. Small Rumin Res 2012; 106 (1): 59 -63.

- Reyna J, Thomson PC, Evans G, Maxwell WM. Synchrony of ovulation and follicular dynamics in merino ewes treated with GnRH in the breeding and nonbreeding seasons. Reprod Domest Anim 2007; 42 (4): 410-417.

- Jordan KM, Inskeep FK, Knights M. Use of gonadotrophin releasing hormone to improve reproductive responses of ewes introduced to rams during seasonal anestrus. Anim Reprod Sci 2009; 116: 254-264.

- Keisler DH, Keisler LW. Formation and function of GnRH-induced subnormal corpora lutea in cyclic ewes. J Reprod Fert 1989; 87: 265-273.

- Karaca F, Ataman MB, Coyan K. Synchronization of estrus with short- and long- term progestagen treatments and the use of GnRH prior to short-term progestagen treatment in ewes. Small Rumin Res 2009; 81: 185-188.

- Hussein MQ, Ababneh MM. A new strategy for superior reproductive performance of ewes bred out-ofseason utilizing progestagen supplement prior to withdrawal of intravaginal pessaries. Theriogenology 2008; 69: 376-383.

- Campbell BK, Mann GE, McNelly AS, Baird DT. The pattern of ovarian inhibin, estradiol and androstenedione secretion during the estrous cycle of the ewe. Endocrinology 1990; 127: 227-235.

- Badinga L, Driancourt MA, Savio JD, Wolfenson D, Drost M, de la Sota RL, Thatcher WW. Endocrine and ovarian responses associates with the first-wave dominant follicle in cattle. Biol Reprod 1992; 47: 871-883.

- Souza CLH, Bruce K, Campbell K, Baird DT. Follicular waves and concentration of steroids and inhibin A in ovarian venous blood during the luteal phase of the estrus cycle in ewes with an ovarian autotransplant. J Endocrinol 1998; 156: 563-572.

- Campbell BK, Scaramuzzi RJ, Webb R. Control of antral follicle development and selection in sheep and cattle. J Reprod Fertil 1995; 49: 335-350.