Review Article - Journal of Finance and Marketing (2018) Volume 2, Issue 1

The role of taxation on resilient economy and development of Rwanda

Jean Bosco Harelimana*

Institute of Higher Education of Ruhengeri, Musanze, Rwanda

- *Corresponding Author:

- Jean Bosco Harelimana

Institute of Higher Education of Ruhengeri

P.O.B. 155 Musanze

Musanze, Rwanda

Tel: +250 783 460 627

E-mail: harelijordan@yahoo.fr

Accepted date: February 07, 2018

Citation: Harelimana JB. The role of taxation on resilient economy and development of Rwanda. J Fin Mark. 2018;2(1):28-39.

DOI: 10.35841/finance-marketing.2.1.28-39

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Finance and MarketingAbstract

The study entitled ‘the role of taxation on resilient economy and development of Rwanda was carried out under the period 2013-2016. The main objective of the study was to assess the role of taxation on economic development. The Methodology such as qualitative and quantitative was used in data collection where both primary and secondary data were collected. A questionnaire was designed to 90 sample sizes out of 920 total employees of RRA purposively selected and a documentary technique was used. After collection, data were analysed using SPSS where a correlation coefficient was determined to measure the relationship between variables. Based on the correlation coefficient r=0.790, we concluded that there is a significant relationship between taxation and Rwanda economic development. Thus 62% of Rwandan economic development should be addressed to taxation for enhancement purposes. It is in this regard RRA should develop goods description standards manual for verification purpose and data analysis and Carry out door to door field visits to identify potential traders to be registered.

Keywords

Taxation, Resilient economy, Revenue and economic development.

Introduction

In African countries, Taxation plays a key role in helping African countries to reach their Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). African governments aim to use taxation to Finance their social and physical infrastructure needs; Provide a stable and predictable fiscal environment to promote economic growth and investment; Promote good governance and accountability by strengthening the relationship between government and citizens; and Ensure that the costs and benefits of development are fairly shared [1]. The role of taxation goes further than promoting economic growth. Tax evasion and the siphoning of funds to tax havens deprive African countries of the fiscal benefits of growth. The development of effective tax responses to counter these challenges is also central to Africa‘s development agenda [2]. In Rwanda, the history indicates that the first tax legislation was inherited from colonial regimes. Such tax legislations include the Ordinance of August 1912 which established graduated tax and tax on real property. There was another Ordinance of 15th November 1925 adopting and putting into application the Order issued in Belgium Congo, on 1st June 1925 establishing a profit tax. The order was amended several times up to the Order of 25th March 1960, meant for Rwanda's development and cash inflow. After independence, the first tax legislation passed was that of 2nd June 1964 governing profit tax, which was repealed and replaced by Law No 8/97 of 26/06/1997 on the Code of Direct Taxes on Different Profits and Professional incomes [3]. This law was amended from time to time in order to keep pace with time and the changing economic environment. Such other legislative instruments include the 1973 law governing property tax, the tax on license to carry out trade and professional activities, the law N°. 29/91 of 28th June 1991 on sales tax /turnover tax (now repealed and replaced by the law N°. 06/2001 of 20/01/2001 on the Code of Value Added Tax (VAT). Other substantive Law governing Customs was enacted on 17th July 1968 accompanying Ministerial Order of 27th July 1968, putting into application the Customs Law [4]. In addition the administration and accountability of taxes and duties in Rwanda was initially under the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. In 1997, Rwanda Revenue Authority was established as an independent body by the law no 15/97 of 8/11/1997 to administer the various taxes and tax related laws and to assess, collect, administer, and account for Fiscal and Customs revenue collected to the Government through the Ministry of finance in accordance with established procedure [5]. In 1994 genocide alluded to left Rwanda with worst scar and near to total destruction of its social fabric. The period before this shows that right from the political setup, no power sharing mechanisms existed. It was characterized by exclusion and authoritarianism down to the economic setup where the meager national resources were in the hands of a few. At the peak of the genocide and its immediate aftermath, the destruction was at such epic proportions that debate was rife in the UN corridors on whether to place Rwanda under UN trusteeship as a failed state. Therefore, the situation required unconventional solutions, stamina and clear focus to reverse this. Clearly it was a fight for life, never mind prosperity. For all, survival was top on the agenda, therefore a common vision was agreed and everybody had to identify their role in this wider set up. Thus, was formed a sustainable partnership and by doing so, it was crucial that accountability be demanded of each other (state and citizens) for this vision to be realized. This scenario was even more profound for Rwanda during the reconstruction process since the need for resources was much greater than ever before.

Funds were needed to rebuild and improve the infrastructure, provide basic services, develop capacity of the citizens, return to the global scene, et cetera, all of which constitute state building. At the same time, the source and composition of these funds had to be predetermined for the long term development agenda. While dependence on aid was inevitable in the immediate term, it was agreed that due to its un-sustainability and inconsistency, it had to be a bridge to a more robust and constant flow of domestic resource mobilization [6]. It was immediately decided that more weight needed to be thrown behind domestically generated resources through taxation. According to research, Commissioner General in Rwanda Revenue Authority (RRA) Rwanda learnt that for her development agenda to be based on domestic resource mobilization (that is, achieve economic growth, lessen extreme inequalities, provide an exit from aid and fund the delivery of the MDGs, significantly improve the lives of all citizens) the establishment of a strong tax system drive to good governance and promote accountability. He said that Rwanda taxation was not merely a tool for raising funds for public expenditure, but also an instrument for building an effective state. Borrowing from other experiences, taxation is viewed as a core manifestation of the social contract between citizens and the state. History has shown that the formation of accountable and effective states has been closely bound up with the emergence of taxation systems. For instance in the developed world, bargaining between rulers and taxpayers helped to give governments an incentive to promote broad economic prosperity and improve public policies in ways that meet citizens’ demands [7]. Unfortunately, this has not been the case for the developing world where citizens were expected to contribute without making any demands on the state. This philosophy held true to Rwanda prior to 1994. Thus taxation reform was singled out as a key ingredient for good governance and state-building. External expertise was acquired with the support of partners with a similar vision for a tax administration such as DFID, and these showed that taxes raised (and spent) transparently would shape the government’s legitimacy as this would promote accountability to its citizens. This would further enhance good governance because to increase political efficiency, taxpayer consent was required. A competent bureaucracy was also necessary for effective resource mobilization and to drive the development agenda forward.

The Rwandan Revenue Authority (RRA) was formed in 1998 to spearhead all reforms in taxation in the country with a mandate to administer, collect and account for all tax and some non-tax revenues and to provide services aimed at promoting business growth. Therefore, Rwanda’s state-building approach through taxation, among other major reforms, was anchored around the establishment of this system (tax policy and its administration), which would strengthen the legitimacy of the state through five core principles political inclusion; accountability and transparency; perceived fairness; effectiveness; and political commitment to shared property (RRA, 2014). It is important to note that since 1998, our revenues have registered a 6.5 fold increment. In real terms, this covers about 78% out of government’s recurrent budget or 52% of the total budget say in 2009 up from a meagre 38% of the recurrent budget in 1998 [8].

The composition of these resources has also reversed within the same period with the larger portion coming from domestic taxes as opposed to the situation in early 2000 where the bulk was from trade taxes. Important to mention is improved revenue collections which has enabled government to undertake pro-poor programs including improvements in national health and reduction of child and maternal mortality, universal free primary education, free fertilizer distribution and progressive strides towards the attainment of MDGs. The tax to GDP ratio has also increased tremendously over the years from approximately 9% in 1998 to over 13% currently. The initial government target was to grow this ratio by at least 0.2% per annum. Due to the consistency and predictability of tax revenues and along with the strong consultative forums between the different stakeholders, Rwanda has been able to link tax revenues to fund the Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (EDPRS) Agenda. The EDPRS is Rwanda’s long term development strategy setting out three flagship programs aimed at enhancing public investment, securing growth and protection for Rwanda’s poorest and most vulnerable, and improving governance. The tax administration has witnessed considerable improvements in compliance levels especially among the large taxpayers (who contribute approximately 75% of the total taxes) which now stand at 97% [9]. To pull the country’s economy out of this situation, the government of Rwanda has had to devise several means including employing its taxation policy this is basically because it’s the main means to raise funds for financing public activities and reducing level of dependency on external fund. However, taxation currently faces a few challenges. For instance the taxpayers themselves are complaining that the tax rates are very high. Eventually, this has more than often resulted into tax evasion and avoidance. Rwandan should know that the government finances all public expenditure from their tax paid like health, education, justice, stability and food security, economic transformation, rural development, increasing productivity and youth employments. RRA introduced the use of Electronic Billing Machines (EBMs) in 2012 to facilitate businesses pay VAT and increase tax-payer compliance while reducing the tax collection/administration cost that has always been a factor of developing economies in Rwanda [10].

RRA collected Rwf 872.3 billion in both tax and non-tax revenues (excluding local government tax collection) during the financial year 2014-2015, representing a 12.7 percent increase compared to the previous fiscal year (RRA Report, 2016). Rwanda Government spends Rwf 1949.4 billion in the 2016-17 fiscal year, Rwf 140.6 billion higher than Rwf 1808.8 billion spent in 2015-2016. Government will finance 62.4% of its budget through domestic revenues amounting to Rwf 1216.4 billion, the remainder of the budget will be funded by external resources worth Rwf 733 billion (37.6% of total budget), with this regards government of Rwanda is reducing dependency on foreign aid where the government have introduced a program of self-reliance common known as Kwigira (MINECOFIN, 2016). According to above background, the researcher is motivated by this research for investigating on which kinds of taxes collected by RRA to stimulate economy? How is economy situation in Rwanda today? How taxes collected by RRA influence economic development of Rwanda? To answer these questions there is a need to carry out the role of taxation on Rwandan economy development by using RRA as a case study [11].

Objectives

The general objective of this study is to evaluate the role of taxation to the development of Rwandan economy specifically:

- To find out the evolution of revenues collected by RRA,

- To assess the determinant factors of resilient economy for economic development of Rwanda

- To establish the relationship between revenue collected by RRA and resilient economy for economic development of Rwanda

Literature Review

Taxation refers to compulsory or coercive money collection by a levying authority, usually a government. The term "taxation" applies to all types of involuntary levies, from income to capital gains to estate taxes. Though taxation can be a noun or verb, it is usually referred to as an act; the resulting revenue is usually called "taxes." Taxation is differentiated from other forms of payment, such as market exchanges, in that taxation does not require consent and is not directly tied to any services rendered. The government compels taxation through an implicit or explicit threat of force [12].

Economic development refers to the process by which GNP per capital increases qualitatively and quantitatively over a very long period of time in the country. It can be measured by the increase in real per capital income and the increase in factors which improve the quality of life of man. For instance, housing, medical care, food and others. The term development itself is wider than economic development or economic welfare or material wellbeing. The term goes further to include improvements in economic, social, and political aspect of the whole society, e.g. Social activities, political institution, security, culture. Therefore, economic development is bigger in context as compared to economic growth [13]. Economic growth can be defined as a quantitative increase in a country’s output. Economic growth is the increase of per capital gross domestic product (GDP) or other measure of aggregate income. It is often measured as the rate of change in GDP economic growth refers only to the quantity of goods and services produced. Economic development can be referred to as the qualitative increase in economic wealth of countries or regions. This concept supposes that legal and institutional adjustments are made to give incentives and motivation for innovation and investment so as to develop an efficient production and distribution system for goods and services. Alternatively, the term economic development can also be used to define a combination of economic growth and factors, which may bring about general cultural, social, educational, political and economic transformation of the district [14].

Researchers carried the study on taxation for investment and development: An overview of policy challenges in Africa. Taxation is central to the current economic development agenda. It provides a stable flow of revenue to finance development priorities, such as strengthening physical infrastructure, and is interwoven with numerous other policy areas, from good governance and formalizing the economy, to spurring growth [15]. Fundamentally, tax policy shapes the environment in which international trade and investment take place. Thus, a core challenge for African countries is finding the optimal balance between a tax regime that is business and investment friendly, and one which can leverage enough revenue for public service delivery to enhance the attractiveness of the economy. A significant share of the tax revenue increase in Africa stems from natural resource taxes, while non-resource-related revenue has increased by less than 1% of GDP over 25 years. This disparity becomes even more challenging against the backdrop of the global economic crisis (with economic growth in Africa expected to decline from 5.7% in 2008 to 2.8% in 2009) and the decrease in commodity prices. To achieve an optimal tax policy, African policymakers are challenged by the need to balance the following imperatives: Mobilizing domestic resources and broadening the tax base to secure steady revenue streams for development financing and to diversify the revenue sources, especially in a context of tariff liberalization that impacts strongly on tax revenue; Fighting Tax evasion, spurred by tax havens, regulatory weaknesses, and some corporate practices; Improving the investment climate for enterprise development, largely shaped by the tax regime; and Promoting good governance, underpinned by effective taxation that promotes the accountability of governments to citizens and the investment community. The OECD can support African countries in addressing these challenges in various ways, from leading global efforts to countering crossborder tax evasion, to working closely with the African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF). The OECD also encourages deeper dialogue with development agencies and donors to transform widespread recognition of the central importance of taxation into effective action [16].

Researchers studied the effects of Income Tax Changes on Economic Growth. This paper examines how changes to the individual income tax affect long-term economic growth. The structure and financing of a tax change are critical to achieving economic growth. Tax rate cuts may encourage individuals to work, save, and invest, but if the tax cuts are not financed by immediate spending cuts they will likely also result in an increased federal budget deficit, which in the longterm will reduce national saving and raise interest rates. The net impact on growth is uncertain, but many estimates suggest it is either small or negative. Base-broadening measures can eliminate the effect of tax rate cuts on budget deficits, but at the same time they also reduce the impact on labor supply, saving, and investment and thus reduce the direct impact on growth [17]. However, they also reallocate resources across sectors toward their highest-value economic use, resulting in increased efficiency and potentially raising the overall size of the economy. The results suggest that not all tax changes will have the same impact on growth. Reforms that improve incentives, reduce existing subsidies, avoid windfall gains, and avoid deficit financing will have more auspicious effects on the long-term size of the economy, but may also create trade-offs between equity and efficiency.

Scientists carried out the study on the impact of income tax rates (ITR) on the economic development of Botswana. Traditional schools of thought advocated the theory of low income tax rates’ influencing economic development, whereas modern schools of thought propagated the theory of higher income tax rates producing greater economic growth, especially for developed nations. In order to justify these thoughts an attempt was made taking Botswana as a case study to pin point the effect of low and high income tax rates on economic growth. In this study various parameters were taken into account including income tax rates, income tax revenue, total revenue and GDP of the country in the nominal and real value of the money. It was located that low income tax rates boosted the economic growth. Researcher carried out the study on Taxes and Economic Growth in Developing Countries: A Dynamic Panel Approach. This paper looks at the effects of taxes increase on economic growth of 47 developing countries. In developing countries, there is no magic tax strategy to encourage economic growth. Some countries with high tax burdens have high growth rates and some countries with low tax burdens have low growth rates. Despite much theoretical and empirical inquiry as well as political and policy controversy, no simple answer exists concerning the relationship of taxes on economic growth in developing countries [18].

The research takes an empirical approach to analyses the effects of four types of taxes namely taxes revenue, taxes on goods and services, taxes on income, profits, and capital gains and taxes on international trade on economic growth. Mobilizing a dynamic panel data over the period 2000–2012 and using the system GMM estimator to address endogenic issues, the econometric results yield that (i) there is a non-linear relationship between taxes revenue and economic growth, specifically, these taxes increase economic growth at short run and this effect then increases over time as these taxes increase (ii) there is a non-linear (U-shaped) relationship between taxes on income, profits and capital gains, taxes on international trade and economic growth, specifically, these taxes lower economic growth at short run and these effects then diminish over time as these taxes increase. Researchers investigated the effect of tax incentives on economic growth in Kenya. Taxation is the key source of revenue that the government of Kenya uses to provide public goods and services to its citizenry. Over the last decade, though revenue collections have increased, the revenues collected have not been sufficient to fund the budget proposals resulting into budget deficits. Raising adequate tax revenues remains a key objective of Kenya’s tax system and therefore, the government must strike a balance between the ever increasing competing development needs and the desire to encourage investments through tax incentives [19]. The budget deficit of a government is a form of a negative saving and a reduction in the deficit can positively influence the net national savings more than any feasible changes in tax policies and encourage savings within an economy which will then stimulate investments. It is therefore important for the government to raise adequate revenue through taxation in order to meet its development agenda.

The objective of the study was to establish the effect of tax incentives on economic growth in Kenya. To achieve this secondary data was used and it was analyzed using descriptive analysis, correlation analysis and regression analysis [20]. The findings showed that there was an inverse relationship between GDP growth rate and tax incentives and GDP growth rate and the stage of development while there was a positive relationship between GDP growth rate and investment levels, GDP growth rate and productive population levels and GDP growth rate and literacy levels. It was further found that the relationship between the GDP growth rate and global competitiveness index, GDP growth rate and level of investments, GDP growth rate and percentage of productive population and GDP growth rate and literacy levels was not statistically significant.

It was concluded that rationalization of the current tax incentive schemes is necessary to ensure that the government is able to enhance collection of revenues to enable it fund the ever increasing budgetary plans and fund its development plans to spur economic growth in the country. The tax incentive schemes in the available must be seen to be beneficial to the economy or support economic growth of the country and as such Kenya should not focus on giving up so as tax expenditures but should focus on optimal tax policies and measures that enhance economic growth. With introduction of e-filing in 2012 in Rwanda, it is believed that e-filing and e-payment will improve tax revenue and bridge the gap of the budget but still there are challenges associated with tax management system making it a problem to achieve their targeted budget. There is no academic research conducted on the use of taxation on development of economy in Rwanda as a gap, and this prompts the researcher to analyses the role of taxation on development of Rwandan economy using current information from RRA [21].

Methodology

This section seeks to examine and understand the methodology that was used to study the role of taxation in the development of Rwandan economy. Tools and techniques and methods had been used to achieve the stated objectives: both primary and secondary data were collected then analyzed so that the correlation and strength between variables can be determined. The study uses correlational as it shows the relationship between taxation and Rwandan economy.

Data analysis

The research is analytical and empirical in nature and makes use of both primary and secondary data. The population for the study is employees RRA. The data has been sourced from employees of RRA, published documents, reports, journals magazines, performance reports, and others documents related to public institutions. This was employed on most documents that could contain any relevant information on the study. The sample period undertaken for the objective is from the year 2013 to 2016.

The sample

The data was collected from 170 sample size out of 295 total populations selected using stratified random sampling techniques. The sample was calculated using Taro Yamane formula elaborated in 1982.

Research instruments

Primary data and secondary data collection had been used in order to achieve the research objectives. The primary data had been collected using questionnaire. The literature review bought about comprehensive review involving the collection of both academic theories and research directly related to the study.

Models and techniques

To find out the relationship between taxation and Rwandan economic, a Pearson correlation coefficient was determined for this purpose.

Results and Findings

In this section, findings and results are presented according to research objectives. During this study at RRA, we found that out of 90 respondents who participated in the study, majority were males. This is justified by the rate of 62.2% respondents who were males. Only 37.8% of respondents were females.

Analysis of revenues collected by RRA

During the study, we found that income taxes are paid out by anyone who earns an income by any means as confirmed on the rate of 92.2%. The income tax filings are due in Rwanda and anyone earning income needs. Income taxes are subject to deductions and tax credits; they are usually not paid by people under a certain income or who have special situations such as a disability.

Property Taxes collected by RRA to help fund in the budgets as confirmed by 92.2% respondents in RRA. More than 94.4% of respondents were confirming the consumptive taxes are paid in RRA from added to the purchase of goods in the stores. Majority of 92.2% respondents confirmed that Corporate Taxes are important when structuring a business as leading channel of Rwandan economy development. The majority of 92.2% respondents confirmed that payroll taxes are received by RRA from businesses before income is distributed to the individual in exchange. The majority of 92.2% respondents confirmed that capital gains taxes from stocks, bonds, and real estate are paid to RRA. More than 92.2% respondents confirmed that Inheritance or Estate Taxes are received in RRA to facilitate economy development.

Annually reports on the evolution of revenues collected by RRA

This report highlights the activities, the successes and the challenges faced by RRA during the past year. The 2015-2016 fiscal year was very successful for RRA. Total tax revenue collections amounted to Rwf 986.7 billion, an achievement rate of 104.3% and a surplus of Rwf 37.5 billion from our original target. This revenue is of vital importance to the country’s development, and through exceeding our target; RRA has been able to contribute even more towards the public spending and self-reliance of Rwanda. This report contains in-depth analysis of tax collections by tax type. It also details the important micro- and macro-economic factors currently affecting tax revenues within Rwanda. This report also details the various administrative measures that have been introduced and enacted to boost revenue collections and service delivery in the 2015-2016 fiscal year (Table 1).

| Real GDP Growth | Inflation | Nom. GDP Growth | Tax Buoyancy | Tax/GDP Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-2012 | 9.5% | 7.5% | 17.6% | 1.18 | 13.4% |

| 2012-2013 | 6.8% | 4.7% | 13.2% | 1.31 | 13.9% |

| 2013-2014 | 5.1% | 3.6% | 9.6% | 1.77 | 14.8% |

| 2014-2015 | 7.3% | 1.1% | 9.4% | 1.34 | 15.3% |

| 2015-2016 | 6.5% | 4.1% | 9.0% | 1.64 | 16.1% |

Table 1. Macroeconomic data by fiscal year, 2011-2016.

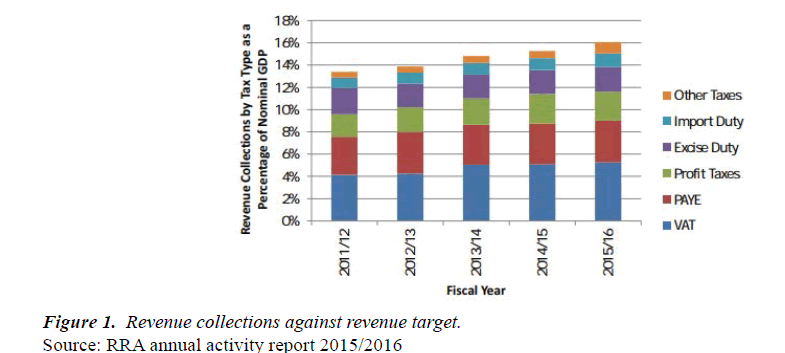

This table displays the contribution of each major tax type to the Tax/GDP ratio over the past five years. Microeconomic factors positively affecting revenue performance where PAYE: Strong growth of the ‘Construction’ and ‘Financial and Insurance Activities’ International Standard for Industrial Classification (ISIC).

PAYE due declared by the ‘Construction’ sector grew by 34.8% year-on-year, a nominal increase of Rwf 1.6 billion. PAYE due declared by the ‘Financial and Insurance Activities’ sector grew by 8.5% year-on-year, a nominal increase of Rwf 2.1 billion. VAT – Electronic Billing Machines (EBMs) are now owned by 11,436 taxpayers. Previous IGC research found that taxpayers using EBMs raised VAT payments by an average of 5.4%. Excise – An amicable agreement with Bralirwa resulted in Rwf 3.5 billion paid in arrears. Import duty – Increased demand for non-EAC imports, which grew by 11.5%, compared to EAC imports, which grew by 0.1%, contributed approximately Rwf 7.3 billion of the Rwf 12.1 billion total nominal increase year-on-year for import duty (Figure 1).

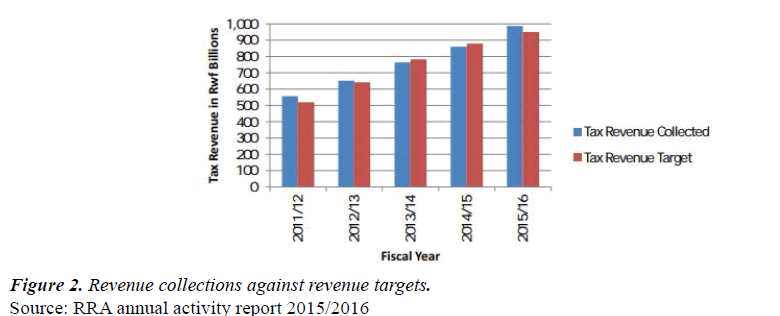

Pay as You Earn collections totaled Rwf 229.7 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This achieved 104.2% of the Rwf 220.5 billion target, a surplus of Rwf 9.2 billion. This represents a year-on-year growth of 11.8%, up from 10.5% growth in 2014-2015 (Figure 2).

In nominal terms, PAYE collections increased by Rwf 24.3 billion year on-year. In terms of declarations, 12,897 taxpayers made PAYE declarations during the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This is a year-on-year decline of 1.9% from the 13,152 taxpayers who declared in 2014-2015. The cause of the decline is the reduction of newly declaring taxpayers of 1,645 in 2015-2016, down from 1,847 in 2014-2015. The number of taxpayers who stopped declaring was comparable to previous years. At an aggregate level, the declarations show year-on-year growth in total employees of 1.5%. The average number of total employees declared each month is 302,550. This represents a nominal increase of 4,488 formal jobs year-on-year. Combined, these taxpayers were paid a total of Rwf 863.7 billion over the 2015-16 tax year period.

This is year-on-year growth of 6.0%. In total, PAYE due declared increased by 7.2% over the 2015-2016 fiscal year. However, PAYE collections are approximately Rwf 14.9 billion higher than PAYE due declared, of which only Rwf 3.5 billion is accounted for in arrears (Table 2).

| Tax Type | Actual 2015-2016 | Target 2015-2016 | Variance | Achievement | Actual 2014-2015 | Growth | Nominal Increase |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAYE | 229.7 | 220.5 | 9.2 | 104.2% | 205.4 | 11.8% | 24.3 |

| Profit Tax (CIT,PIT and WHT) |

159.3 | 167.3 | -7.9 | 95.3% | 150.7 | 5.8% | 8.7 |

| VAT | 323.2 | 305.0 | 18.2 | 106.0% | 286.2 | 12.9% | 37.0 |

| VAT Customs | 109.1 | 99.9 | 9.2 | 109.2% | 99.8 | 9.3% | 9.3 |

| VAT Domestic | 214.1 | 205.1 | 9.0 | 104.4% | 186.5 | 14.8% | 27.6 |

| Excise Duties | 138.1 | 135.5 | 2.6 | 101.9% | 120.6 | 14.4% | 17.4 |

| Excise Customs | 67.5 | 66.9 | 0.6 | 100.9% | 60.8 | 11.1% | 6.8 |

| Excise Domestic | 70.5 | 68.6 | 2.0 | 102.9% | 59.9 | 17.8% | 10.7 |

| Mining Royalties | 3.0 | 5.2 | -2.2 | 58.2% | 4.2 | -27.5% | -1.1 |

| Import Duties | 72.9 | 59.9 | 13.0 | 121.7% | 60.8 | 19.9% | 12.1 |

| Road Fund | 37.3 | 31.5 | 5.8 | 118.3% | 25.9 | 44.1% | 11.4 |

| SR Levy | 8.7 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 100.3% | 0.0 | 8.7 | |

| ID Levy | 8.8 | 10.6 | -1.8 | 82.6% | 0.0 | 8.8 | |

| Others Taxes | 5.74 | 5.13 | 0.61 | 112.0% | 5.35 | 7.4% | 0.39 |

| Total | 986.7 | 949.2 | 37.5 | 103.9% | 859.1 | 14.8% | 127.5 |

Table 2. Tax revenue collections by tax type, in Rwf billions.

Source:RRA Annual Activity Report 2015-2016.

Disaggregating by ISIC sections, the most notable performance comes from ‘Construction’ and ‘Financial and Insurance Activities’. Construction has only increased employees by 1.1% year-on-year in 2015-2016, but has increased remuneration by 30.5% leading to a total increase in PAYE due declared of 34.8%. In nominal terms, this has increased PAYE due declared by Rwf 1.6 billion year-on-year to a total PAYE due declared of Rwf 6.3 billion in the 2015- 2016 fiscal year.

The construction sector now accounts for 8.3% of all employees and 3.0% of total PAYE due. This strong performance has largely resulted from the current construction boom in Kigali. Notable taxpayers include ‘Summa Turizm Yatirimciligi Anonim Sirketi’, a new taxpayer who declared Rwf 0.6 billion PAYE due, as well as existing taxpayers ‘NPD Cotraco SARL’, ‘Horizon Construction’, ‘Real Contractors Ltd’ and ‘Roko Construction’ whose PAYE due declared increased year-on-year by Rwf 0.4 billion, Rwf 0.3 billion, Rwf 0.2 billion and Rwf 0.2 billion respectively. The financial and insurance sector has increased their employees by 5.3% year-on-year in 2015-2016, whilst remuneration has increased by 7.5% resulting in an increase in PAYE due declared of 8.5%. In nominal terms, this has increased PAYE due declared by Rwf 2.1 billion year-on-year to a total PAYE due declared of Rwf 27.3 billion in the 2015-2016 fisal year. The financial and insurance sector now accounts for 4.2% of all employees and 12.7% of total PAYE due declared. This strong performance has benefited from large bank bonuses to employees.

Profit taxes

Corporate income tax (CIT) and personal income tax (PIT): CIT and PIT collections totaled Rwf 63.2 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This achieved 97.9% of the Rwf 64.5 billion target, a shortfall of Rwf 1.4 billion. This represents a year-on-year growth of 8.2%, down from 22.2% growth in 2014-2015. In nominal terms, profit taxes collections increased by Rwf 4.8 billion year-on years. CIT and PIT can be declared as real regime, lump sum or flat amount depending upon the size of the business. Real regime includes the full, accounting format, details.

The main reason CIT and PIT trends may differ from VAT trends is because real regime CIT and PIT declarations take into account varying factors such as operating expenses, depreciation and investment allowances. In terms of declarations, the total number of taxpayers declaring CIT and PIT combined was 52,051. This is a year-on-year increase of 4.2% from the 49,941 taxpayers who declared in 2014-2015. Disaggregating by tax type, 25,678 taxpayers declared CIT in 2015-2016. This is an increase of 13.2% on the 22,689 who declared in 2014-2015. In contrast, 26,373 taxpayers declared PIT in 2015-2016. This is a decrease of -3.2% of the 27,252 who declared in 2014-2015. Combined, the business income (turnover) of PIT and CIT declarations totaled Rwf 4,285.6 billion for the 2015 calendar year. This represents year-on-year growth of 9.7% from the Rwf 3,907.9 billion declared for the 2014 calendar year. Furthermore, the CIT Payable and PIT Payable (including Annual Flat Tax Due) totaled Rwf 56.2 billion for the 2015 calendar year. This represents year-on-year growth of 10.4% from the Rwf 50.8 billion declared for the 2014 calendar year. Focusing on payments by taxpayer and disaggregating by ISIC sections, there are many notable aspects of performance. However, it is first important to clarify that Profit Taxes are acknowledged as a volatile tax type, year-to-year. This volatility is caused by significant variations in incomes, investment and depreciation year-to-year. Comparing 2015- 2016 and 2014-2015 payments, there are some significant falls in ‘Construction’ and ‘Transportation and Storage’. In particular, payments from the construction sector were Rwf 5.9 billion in 2015-2016, down Rwf 8.4 billion from the Rwf 14.3 billion paid in 2014-2015. Payments from the construction sector accounted for 9.8% of all profit tax payments in 2015-2016, down from 23.8% in 2014-2015. In addition, payments from the transportation and storage sector were Rwf 2.7 billion in 2015-2016, down Rwf 5.4 billion from the Rwf 8.1 billion paid in 2014-2015. Payments from the transportation and storage sector accounted for 4.6% of all profit tax payments in 2015-2016, down from 13.6% in 2014-2015 (RRA, 2015-2016). On the other hand, there were large increases in payments from the ‘Financial and Insurance Activities’, ‘Information and Communication’ and ‘Manufacturing’ sectors. Most importantly, payments from the financial and insurance sector were Rwf 15.3 billion in 2015-2016, up Rwf 10.3 billion from the Rwf 5.0 billion paid in 2014-2015. Payments from the financial and insurance sector accounted for 25.6% of all profit tax payments in 2015- 2016, up from 8.4% in 2014-2015. Moreover, payments from the information and communication were Rwf 6.7 billion in 2015-2016, up Rwf 6.5 billion from the Rwf 0.1 billion paid in 2014-2015. Payments from the information and communication sector accounted for 11.1% of all profit tax payments in 2015-2016, up from 0.2% in 2014-2015.

Lastly, payments from the manufacturing sector were Rwf 7.4 billion in 2015-2016, up Rwf 5.2 billion from the Rwf 2.1 billion paid in 2014-2015. Payments from the manufacturing sector accounted for 12.3% of all profit tax payments in 2015-2016, up from 3.6% in 2014-2015. Listing in descending order of total CIT and PIT payments (including prepayments), the top 100 highestpaying taxpayers accounted for 71.7% of total CIT and PIT payments in 2015-2016. This is diversified slightly from 73.3% for the similar statistic in the 2014-2015 fiscal year.

Withholding 15% (WHT 15%): Withholding 15% collections totaled Rwf 61.5 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This achieved 90.8% of the Rwf 67.7 billion target, a shortfall of Rwf 6.2 billion. This represents a year-onyear growth of 4.4%, down from 28.2% in 2014-2015. In nominal terms, WHT 15% collections increased by Rwf 2.6 billion year-on-year. This poor performance was mainly caused by low government spending. Disaggregating by ISIC section, payments from the ‘Public Administration and Defense; Compulsory Social Security’ section and including National Bank of Rwanda (BNR) were Rwf 26.1 billion in 2015-2016. This is down Rwf 0.7 billion from the Rwf 26.7 billion paid in 2014-2015. Payments from the ‘Public Administration and Defense; Compulsory Social Security’ section accounted for 42.3% of all WHT 15% payments in 2015-2016, down from 44.0% in 2014-2015. The other ISIC section that underperformed was ‘Wholesale and Retail Trade’. Payments from the wholesale and retail trade sector were Rwf 1.3 billion in 2015-2016. This is down Rwf 1.1 billion from the Rwf 2.4 billion paid in 2014-2015. Payments from the wholesale and retail trade sector accounted for 2.1% of all WHT 15% payments in 2015-2016, down from 3.9% in 2014-2015.

Withholding 3% (WHT 3%): Withholding 3% collections totaled Rwf 18.1 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This achieved 81.2% of the Rwf 22.3 billion target, a shortfall of Rwf 4.2 billion. This represents a year-on-year reduction of 11.0%, down from 17.5% increase in 2014-2015. In nominal terms, WHT 3% collections decreased by Rwf 2.2 billion year-on-year. As with Withholding 15%, this poor performance is largely caused by low government spending. Disaggregating by ISIC section, payments from the ‘Public Administration and Defense; Compulsory Social Security’ and including National Bank of Rwanda (BNR) were Rwf 11.0 billion in 2015-2016. This is down Rwf 2.0 billion from the Rwf 13.0 billion paid in 2014-2015. Payments from the ‘Public Administration and Defense; Compulsory Social Security’ section and BNR accounted for 60.7% of all WHT 3% payments in 2015-2016, down from 63.7% in 2014-2015.

Value added tax (VAT)

Value Added Tax collections are all reported net of refunds. This means that only 90% of the total collections are reported, as the remaining 10% is retained for allocating as VAT refunds. Value Added Tax collections totaled Rwf 323.2 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This achieved 106.0% of the Rwf 305.0 billion target, a surplus of Rwf 18.2 billion. This represents a year-on-year growth of 12.9%, up from 10.5% growth in 2014-2015. In nominal terms, VAT collections increased by Rwf 37.0 billion years-on-year.

VAT customs: VAT is collected on imports at customs, as well as domestically. Disaggregating at this level, VAT customs collections totaled Rwf 109.1 billion in the 2015- 2016 fiscal year. This achieved 109.2 % of the Rwf 99.9 billion target, a surplus of Rwf 9.2 billion. This represents a year-onyear growth of 9.3%, down from the 10.2% growth in 2014- 2015. In nominal terms, VAT customs collections increased by Rwf 9.3 billion year on-year. As the ‘International Trade Taxes’ analysis explains, VAT customs benefited from the significant exchange rate depreciation in 2015-2016. This is estimated to have contributed Rwf 7.2 billion to the Rwf 9.3 billion nominal increase year-on-year.

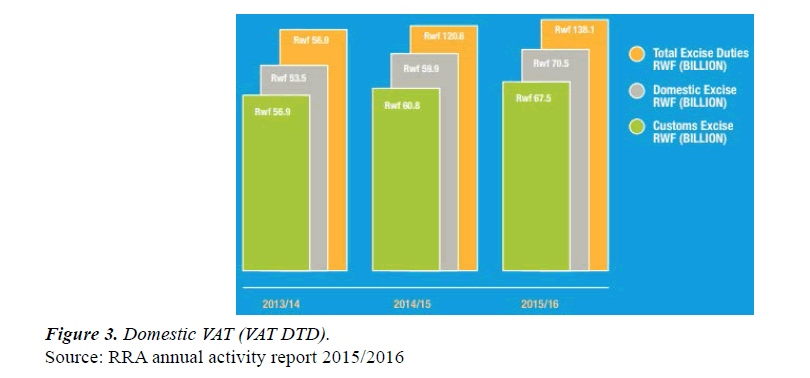

Domestic VAT (VAT DTD): In terms of the Domestic Taxes Department (DTD), VAT DTD collections totaled Rwf 214.1 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This achieved 104.4% of the Rwf 205.1 billion target, a surplus of Rwf 9.0 billion. This represents a year-on-year growth of 14.8%, up from the 10.6% growth in 2014-2015. In nominal terms, VAT DTD collections increased by Rwf 27.6 billion yearon- year. Firstly, analysis will focus on the VAT collected by the Domestic Taxes Department (DTD), which is made up of the Small and Medium Taxpayers Office (SMTO) and the Large Taxpayers Office (LTO). At the DTD level, in terms of declarations, 15,139 taxpayers made VAT declarations during the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This is a year-on-year growth of 15.3% from the 13,135 taxpayers who declared in 2014-2015. Of the 15,139 taxpayers who made VAT declarations during the 2015-2016 fiscal year, 2,729 taxpayers had not declared VAT in 2014-2015. In contrast, 725 taxpayers did not declare VAT in 2015-2016, which previously had in 2014-2015. At an aggregate level, the VAT declarations show year-on-year growth in turnover of 12.6%. The total turnover declared in 2015-2016 was Rwf 4,291.2 billion. Of this turnover, 37.0% was declared as non-taxable for VAT purposes, against 63.0% that was taxable. Of the non-taxable turnover, Rwf 1,283.4 billion was declared as exempt, 29.9% of turnover; Rwf 75.3 billion was declared as zero-rated, 1.8% of turnover; and Rwf 229.4 billion was declared as exports, 5.3% of turnover [22].

The total output VAT, VAT on taxable sales, was Rwf 486.6 billion in 2015-2016. This represents year-on-year growth of output VAT of 16.0% from the Rwf 419.5 billion declared in 2014-2015. Against this, the input VAT, VAT paid on inputs, was Rwf 306.0 billion. This represents yearon- year growth of input VAT of 14.3% from the Rwf 267.8 billion declared in 2014-2015. The input VAT in 2015-2016 is made up of 30.2% imports, whilst 69.8% is from domestic purchases. The total of VAT refunds claimed was Rwf 30.2 billion in 2015-2016. This represents year-on-year growth of 6.3% from the Rwf 28.4 billion that was claimed in 2014- 2015. Finally, the declarations calculate total VAT = VAT Due + VAT Withheld by Public Institutions (VAT WHT). Aggregating across all declarations, total VAT declared was Rwf 220.7 billion in 2015-2016. This represents year-onyear growth of 17.4% from the Rwf 188.0 billion declared in 2014-2015. The total VAT in 2015-2016 is made up of 74.6% VAT Due, whilst Rwf 25.4% is from VAT Withheld by Public Institutions. Disaggregating by ISIC sections, there are many notable aspects of performance. Firstly, the ‘Construction’ sector declared total VAT of Rwf 36.7 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year, up Rwf 10.9 billion from the Rwf 25.8 billion declared in 2014-2015. Total VAT declared from the construction sector accounted for 16.6% of total VAT declared in 2015-2016, up from 13.7% in 2014-2015. In addition, the ‘Wholesale and Retail Trade’ sector declared total VAT of Rwf 35.8 billion in 2015-2016, up Rwf 5.2 billion from the Rwf 30.6 billion declared in 2014-2015. Total VAT declared from the wholesale and retail trade sector accounted for 16.2% of the total VAT declared in 2015-2016, slightly down from 16.3% in 2014-2015. In contrast, the ‘Mining and Quarrying’ sector declared total VAT of Rwf 0.4 billion in 2015-2016, down Rwf 1.7 billion from the Rwf 2.1 billion declared in 2014-2015. Total VAT declared from the mining and quarrying sector accounted for 0.2% of the total VAT declared in 2015-2016, down from 1.1% in 2014- 2015. As will be discussed further in the mining royalties’ analysis, the global fall in mineral prices has harmed the mining and quarrying sector. However, the policy change of zero-rating minerals for VAT purposes would have affected VAT collections regardless. Also underperforming was the ‘Accommodation and Food Service Activities’ sector, which declared total VAT of Rwf 7.3 billion in 2015-2016, very slightly down from the Rwf 7.3 billion that was also collected in 2014-2015. This lack of growth meant that the total VAT declared from the accommodation and food service activities sector accounted for 3.3% of the total VAT declared in 2015- 2016, down from 3.9% in 2014-2015 (Figure 3).

Excise duties

In total, excise duty collections were Rwf 138.1 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This achieved 101.9% of the Rwf 135.5 billion target, a surplus of Rwf 2.6 billion. This represents year-on-year growth of 14.4%, up from 9.2% growth in 2014-2015. In nominal terms, excise duties collections increased by Rwf 17.4 billion year-on-year.

Excise customs: Customs excise collections were Rwf 67.5 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This achieved 100.9% of the Rwf 66.9 billion target, a surplus of Rwf 0.6 billion. This represents a year-on-year growth of 11.1%, up from 6.8% growth in 2014-2015. As the ‘International Trade Taxes’ analysis explains, customs excise benefited from the significant exchange rate depreciation. This is estimated to have contributed Rwf 3.3 billion to the Rwf 6.8 billion nominal increase year-on-year. The largest contributing product to customs excise collections is petroleum. Customs excise on petroleum product collections totaled customs collections. Table 3 below displays the increased volume of fuel imports in 2015-2016.

Excise domestic: As with VAT, excise duties are collected at customs as well as domestically. Domestic excise collections were Rwf 70.5 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This achieved Rwf 102.9% of the Rwf 68.6 billion target, a surplus of Rwf 2.0 billion. This represents year-onyear growth of 17.8%, up from 11.8% growth in 2014-2015. In nominal terms, domestic excise collections increased by Rwf 10.7 billion years-on-year. Domestic excise collections benefited from an amicable agreement with Bralirwa who paid Rwf 3.5 billion in arrears over September, October and November 2015. The largest contributing product to domestic excise collections is beer. Domestic excise on beer collections totaled Rwf 45.9 billion in 2015-2016. This is up Rwf 9.0 billion from the Rwf 36.9 billion collected in 2014- 2015. This includes the Rwf 3.5 billion paid by Bralirwa in arrears. Excluding the arrears, this represents year-on year growth of 14.9% in 2015-2016, up from 7.0% in 2014-2015. Domestic excise on beer accounts for 65.0% of domestic excise collections in 2015-2016, up from 61.7% in 2014- 2015 [23].

Excise tobacco: The only policy change affecting excise collections in 2015-2016 was for excise on tobacco. This affects both domestic and customs collections. This policy change approximately doubled the price of cigarettes in Rwanda. In total, excise tobacco collections totaled Rwf 7.7 billion in 2015-2016. This represents a year on-year growth of 44.8% from the Rwf 5.3 billion collected in 2014-2015. The policy change accounted for Rwf 1.4 billion of this increase, but far less than the Rwf 5.0 billion addition targeted.

Analysis of determinants of Rwandan economic development

The results were found confirming that the quality of natural resources available increase the level of output of goods that attained in Rwanda was confirmed on the rate of 94.4%. Availability of natural resources is the ability to bring them into use as growth of an economy was confirmed by 95.6% respondents during this study at RRA. Setting up of more factories equipped with machines and tools raise the productive capacity of the economy confirmed by 98.9% respondents at RRA. Capital formation is core of economic development in Rwanda was confirmed by 93.3% respondents during this study at RRA. Using advanced technology brings significant increase in per capita output was confirmed by 92.2% respondents during this study at RRA. The growing population increases the level of output was confirmed by 95.6% respondents during this study at RRA. Growing population means growing market for goods which facilitates the process of growth were confirmed on the rate of 94.4%. The Rwandan economy is based on the largely rain-fed agricultural production of small, semisubsistence, and increasingly fragmented farm was confirmed by 93.3% respondents during this study at RRA. The sustained economic growth has succeeded when reducing poverty rate of citizens was confirmed on the rate of 93.3%. A great number of new areas have become electrified through an expansion of infrastructure was confirmed by 90.0% respondents during this study at RRA [13].

Relationship between taxation and resilient economy of economic development of Rwanda

The results revealed Government of Rwanda uses taxes for building public infrastructures like roads, schools and hospitals was confirmed by 94.4% respondents during this study at RRA. Taxes collection facilities help Government of Rwanda to support public projects using their budgets was confirmed by 92.2% respondents during this study at RRA. Using taxes helps to stimulate Rwandan economy development was confirmed by 94.4%. This is justified by P-value which equals 0.000 less than Alpha (0.05). This is an indicator of relationship between revenue collected by RRA contributes on Rwandan economic development. The level of relationship is 0.790 from interval statistic 0.7 ≤ p < 0.9 categorized as High Correlation. Significant level is 0.05 (5%), the P-Value of 0.000 or (0%) which is less than 5% of Alpha. In other words, when taxation is effectively done, there is an increase of Rwandan economic development. This is correlated at a high level and this normal for social sciences whereby strong or perfect correlation is found in exact sciences. This helps to confirm that there is significant relationship between taxation and Rwandan economic development. Rwf 50.1 billion in 2015-2016. This is up Rwf 9.0 billion from the Rwf 41.1 billion collected in 2014-2015. This represents year-on-year growth of 22.1% in 2015-2016, up from 11.0% in 2014-2015. Customs excise on petroleum products accounts for 74.7 % of excise collections in 2015- 2016, up from 67.5% in 2014-2015. The decreasing global oil price has increased demand for petroleum products in Rwanda. As the excise duty is applied at a specific rate per liter, rather than ad valorem, this has benefited excise customs collections. Table 3 below displays the increased volume of fuel imports in 2015-2016.

| Fiscal Year | Million Liters of Fuel Imported | Year-on-Year Growth | Nominal Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-2012 | 218.6 | 17.5 | 32.6 |

| 2012-2013 | 233.5 | 6.8 | 14.9 |

| 2013-2014 | 254.1 | 8.8 | 20.5 |

| 2014-2015 | 264.5 | 4.1 | 10.4 |

| 2015-2016 | 326.2 | 23.3 | 61.7 |

Table 3. Volume of fuel imports, by fiscal year.

Excise domestic: As with VAT, excise duties are collected at customs as well as domestically. Domestic excise collections were Rwf 70.5 billion in the 2015-2016 fiscal year. This achieved Rwf 102.9% of the Rwf 68.6 billion target, a surplus of Rwf 2.0 billion. This represents year-onyear growth of 17.8%, up from 11.8% growth in 2014-2015. In nominal terms, domestic excise collections increased by Rwf 10.7 billion years-on-year. Domestic excise collections benefited from an amicable agreement with Bralirwa who paid Rwf 3.5 billion in arrears over September, October and November 2015. The largest contributing product to domestic excise collections is beer. Domestic excise on beer collections totaled Rwf 45.9 billion in 2015-2016. This is up Rwf 9.0 billion from the Rwf 36.9 billion collected in 2014- 2015. This includes the Rwf 3.5 billion paid by Bralirwa in arrears. Excluding the arrears, this represents year-on year growth of 14.9% in 2015-2016, up from 7.0% in 2014-2015. Domestic excise on beer accounts for 65.0% of domestic excise collections in 2015-2016, up from 61.7% in 2014- 2015 [23].

Excise tobacco: The only policy change