Case Report - Current Trends in Cardiology (2017) Volume 1, Issue 2

The mystery of a deadly recurrent constrictive pericarditis: TB or not TB?

- *Corresponding Author:

- Kenechukwu Mezue

Department of Medicine, Einstein Medical Center

Suite 303, Klein Building Philadelphia, PA 19141, USA

Tel: +1 323-786-3983

Fax: +1 215-456-792

E-mail: MezueKen@einstein.edu

Accepted March 29, 2017

Citation: Mezue K, Mostafavitoroghi S, Ram P, et al.. The mystery of a deadly recurrent constrictive pericarditis: TB or not TB?. Curr Trend Cardiol. 2017;1(1):31-33.

DOI: 10.35841/cardiology.1.2.31-33

Visit for more related articles at Current Trends in CardiologyAbstract

Constrictive pericarditis is characterized by scarring and loss of elasticity of the Pericardium, and subsequently, this leads to signs and symptoms of right heart failure. Common etiologies include previous cardiac surgery, repeated pericarditis, and Radiation therapy. However, less common causes include tuberculosis, neoplasms, and autoimmune disorders. Here we present a rare case of constrictive pericarditis of possible tuberculous etiology and review the diagnosis and management of the condition.

Introduction

Constrictive pericarditis is characterized by scarring and loss of elasticity of the pericardium, and subsequently, this leads to signs and symptoms of right heart failure. Common etiologies include previous cardiac surgery, repeated pericarditis, and radiation therapy. However, less common causes include tuberculosis, neoplasms, and autoimmune disorders. Here we present a rare case of constrictive pericarditis of possible tuberculous etiology and review the diagnosis and management of the condition.

Case

A 68-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension, immune thrombocytopenia, and early cervical cancer (who had been cured surgically with a hysterectomy) presented with worsening shortness of breath on exertion and leg swelling of four weeks duration. She also had an occasional cough productive of whitish sputum. She has a history of contact with active tuberculosis (her father), and she was diagnosed with latent tuberculosis (TB) infection at an early age but did not complete a course of treatment for latent TB. The patient denied having chest pain, fever, and chills, weight loss, night sweat, or malaise. Her physical exam was remarkable for jugular venous distension, positive Kussmaul sign, hepatomegaly, and bilateral lower extremities edema.

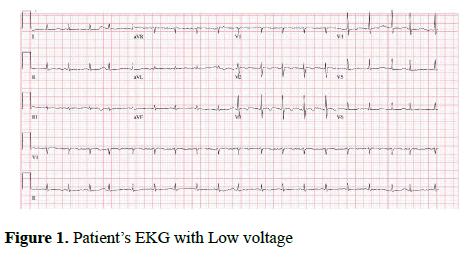

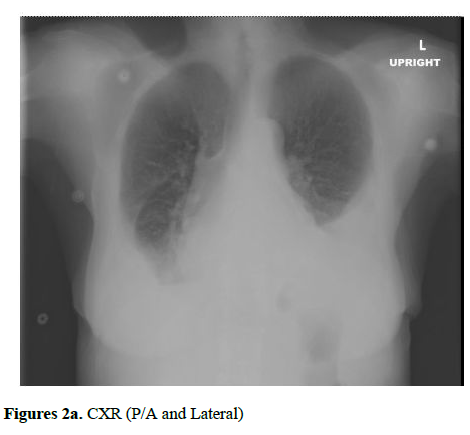

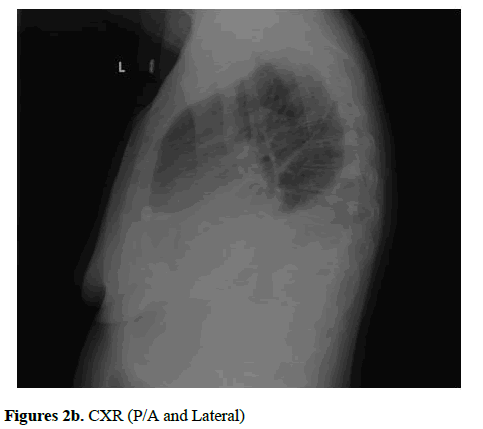

Initial labs were significant for thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 15 000/cm3, B-type natriuretic protein (BNP) 270, international normalized ratio (INR) 1.3, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 316, and total bilirubin 2.1 (direct bilirubin 1.1). Other lab values including haemoglobin levels, white blood cell count, renal function, and electrolytes were within normal limits. Her EKG showed low voltage QRS complexes in limb leads and T-wave inversion in anterior leads (Figure 1). HIV antibody screen and hepatitis panel were negative. PPD test was positive (15 mm) and chest X-ray showed bilateral pleural effusion and a calcified pericardium (Figures 2a and 2b).

A thoracentesis was exudative by Light’s criteria and negative for acid-fast bacilli and malignant cells. However, the drainage of the pleural fluid provided the patient with symptomatic relief. Two-dimensional echocardiogram showed prominent septal bounce suggestive of ventricular interdependence and an ejection fraction of 45-50% without segmental wall motion abnormality. The right ventricle appeared to have normal size but was compressed externally by a loculated structure leading to its moderate systolic dysfunction. Right and left heart catheterization was performed which showed significant diastolic equilibration of diastolic pressures consistent with constrictive pericarditis. No evidence of coronary artery disease was seen.

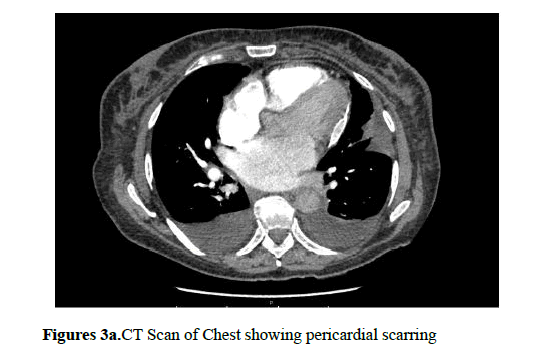

The cardiothoracic surgery team was consulted given the echocardiogram, and cardiac catheterization findings and a pericardiectomy was performed. Intra-operative observations showed an inflammatory process and fibrinous collections along the diaphragmatic surface of the heart, extending anteriorly onto the right ventricle and over the right atrium; along with extensive calcification of the diaphragmatic surface of the right ventricle and posteroinferior left ventricle. The pericardium was resected along with dissection of the calcified adhesions. Post-operative transthoracic echocardiogram (TEE) confirmed improved right ventricular function. The pericardial biopsy showed fibro connective tissue with dystrophic calcification, mixed acute and chronic inflammation and associated fibrin. However, the bilateral pleural effusions persisted, and a pleural biopsy was performed using videoassisted thoracoscopy, and this showed fibrosing pleuritis with fibrin deposition and granulation tissue, no AFB was seen. The patient was re-admitted due to similar symptoms two months later and developed a massive right pleural effusion, progressively worsening heart failure and eventually died of cardiogenic shock.

Discussion

In constrictive pericarditis (CP) a thickened, scarred, and often calcified pericardium limits the heart’s compliance and subsequently decreases diastolic filling [1]. This will in turn cause dissociation between intra-thoracic and intra-cardiac pressures, increased inter-ventricular dependence causing a right-to-left septal shift, and increased diastolic filling pressures with pressure equalization in all four cardiac chambers [2].

CP can be diagnosed via different modalities

Doppler echocardiography, in which pericardial thickening, septal bounce, the diminished collapse of the inferior vena cava (IVC), and reversal of flow in expiration in the hepatic veins are suggestive findings.

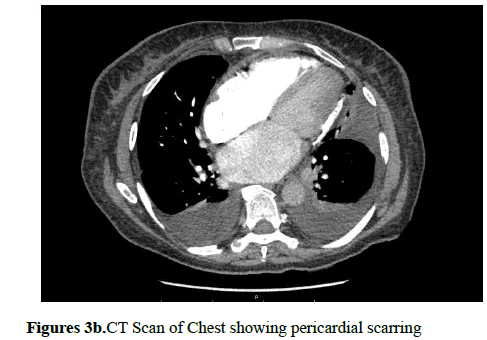

Cardiac MRI or cardiac CT is also useful in diagnosing CP as they can show pericardial thickening and calcification. These can particularly be helpful when echocardiographic findings are inconclusive (Figures 3a and 3b).

Hemodynamic assessment by cardiac catheterization which can be suggestive by showing equalization of diastolic pressures in four chambers and rapid early diastolic ventricular filling (dipand- plateau pattern) [3,4]. An endomyocardial or pericardial biopsy may be required in rare cases to distinguish a restrictive cardiomyopathy from constrictive pericarditis. The most common etiologies of constrictive pericarditis include post cardiac surgery, radiotherapy, connective tissue disorders, cancer and infections such as tuberculosis (TB) [1,4]. The condition can also rarely occur idiopathically and also in other rare conditions such as IgG4 disease and Whipple’s disease. Pericardial involvement due to cancer usually presents as pericardial effusion, mainly secondary to metastases arising from either solid tumors or leukemia. Although our case had a history of cervical cancer, this type of cancer is very uncommon among solid tumours causing metastatic CP while lung and breast cancer are highest on this list [4]. Additionally, she did not have a history of radiotherapy. While tuberculosis (TB) remains a common cause in developing countries and immunosuppressed patients; it is rare in non-endemic areas and immunocompetent patients [6]. Extra pulmonary TB occurs in 20% of patients. A life-threatening form of it is TB pericarditis, also known as Transkei heart, which can present as pericardial effusion (80%), constrictive pericarditis (5%), or a combination of both (15%) [3,5]. Mycobacterium tuberculosis spreads to pericardium via retrograde lymphatic or haematogenous route. The immune response to the protein antigens of the acid-fast bacilli and the delayed hypersensitivity responses, with eventual granuloma formation and fibrosis, is the responsible pathogenesis [6]. Mortality in TB pericarditis is as high as 90% without treatment whereas anti-TB therapy can reduce the mortality to fewer than 20-30%. The most serious sequel of TB pericarditis is constrictive pericarditis, and its management requires prompt initiation of anti-TB therapy [2].

In the present case, despite a history of incompletely treated LTBI; no active sign and symptom of active TB was found. Multiple negative AFB samples also argued against this diagnosis and resulted in a reluctance to initiate TB treatment. However, constrictive pericarditis can be seen in the later stages of a subtle TB pericarditis. In these cases, histological evidence of necrotizing granuloma is seen in a pericardial biopsy with negative microbiological evidence of the microorganism [7]. On the other hand, pericardial biopsy has a high false negative rate for TB [5]. This and the fact that all other possible differential diagnoses were unlikely led us to the diagnosis of TB constrictive pericarditis.

Severity and chronicity of symptoms in our patient warranted pericardectomy, which was appropriately done. However, she developed right heart failure again two months after the pericardiectomy which was thought to be secondary to recurrent constrictive pericarditis. Recurrent constrictive pericarditis after pericardiectomy has rarely been reported before [8] and can be due to several reasons including incomplete pericardiectomy, recurrent constriction which is unlikely in our case given the short time frame, or extension of the calcification into the myocardium.

References

- Hoit BD. Pathophysiology of the Pericardium. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2016.

- Tse G, Ali A, Alpendurada F, et al. Tuberculous Constrictive Pericarditis. Res Cardiovasc Med. 2015;4:e29614.

- Syed FF, Mayosi BM. A modern approach to tuberculous pericarditis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis.2007;50:218-36.

- Marta L, Alves M, Peres M, et al. Effusive-constrictive pericarditis as the manifestation of an unexpected diagnosis. Portuguese J Cardiol. 2015;34:69.e1-6.

- Denk A, Kobat MA, Balin SO, et al. Tuberculous pericarditis: a case report. Le infezioni in medicina : rivista periodica di eziologia, epidemiologia, diagnostica, clinica e terapia delle patologie infettive. 2016;24:337-9.

- Mayosi BM, Burgess LJ, Doubell AF. Tuberculous pericarditis. Circulation. 2005;112:3608-16.

- Butany J, El Demellawy D, Collins MJ, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: case presentation and a review of the literature. Can J Cardiol. 2004;20:1137-44.

- Ferreira R, Gonzaga A, Santos L, et al. Recurrent constrictive pericarditis: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Portuguese J Cardiol. 2015;34:421.e1-5.