Research Article - Biomedical Research (2016) Computational Life Sciences and Smarter Technological Advancement

The correlation of healthy skin thickness and echogenicity with age, anatomic site and gender by high-frequency ultrasound

Sili Ni, Hua Wang, Xiaoyan Luo, Chunhua Tan, Qi Tan, Liqiang Gan*Department of Dermatology, the Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Child Development and Disorders, Chongqing 400014, China

- *Corresponding Author:

- Liqiang Gan

Department of Dermatology

The Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University

China

Accepted date: March 25, 2016

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the correlation of healthy skin thickness and echogenicity with age, anatomic site and gender by high-frequency ultrasound.

Methods: A total of 82 Chinese children in our department were selected as subjects, whose healthy skin thickness and echogenicity was measured using high-frequency ultrasound (DermaLab Combo, Cortex, Denmark) to examine whether there was statistical difference in skin thickness among different ages, anatomic sites and genders.

Results: There was statistical difference in skin thickness and echogenicity among different anatomic sites and age groups (P<0.05); there was no statistical difference in skin thickness and echogenicity between different genders (t=0.49; P>0.05).

Conclusion: High-frequency ultrasound can accurately measure the healthy skin thickness and echogenicity in children. Skin thickness and skin echogenicity is correlated with anatomic site and age, but not correlated with gender.

Keywords

Twenty MHz Ultrasound, Chinese children, Skin thickness, Skin echogenicity.

Introduction

Ultrasound is a valuable diagnostic tool widely used in medicine. During the last three decades, this non-invasive skin imaging method has been extended to dermatology [1]. The clinical applications of high-frequency ultrasonography are quickly expanding. This dermatologic diagnostic technique provides a precise, sensitive, noninvasive and reproducible method of skin evaluation, which enables objective visualization in vivo providing information on the dynamics of the pathologic processes and skin reaction to therapy applied [2]. The measurement of skin thickness is one of the main applications for ultrasound imaging. Skin thickness changes may be due to acanthosis, atrophy, edema, collagen accumulation and its configuration, degree of hydration in the dermis or inflammatory cell infiltration [3]. Ultrasound of skin is non-invasive and therefore attractive to use in children, High-frequency ultrasound can provide a precise and reliable tool for assessment of the cutaneous and subcutaneous thickness in children [4]. However, little attention has been paid to the instrumental investigation of the structure of the children’s skin and there is no study for the Chinese children. The aim of our study was to evaluate skin thickness and echogenicity at different sites in Chinese subjects aged 0-12 years by 20 MHz Ultrasound. We now report one of the largest case series to date, that of 82 Chinese children assessed by 20- MHz Ultrasound, including our experience with their skin thickness and skin echogenicity.

Methods

From October 2012 to October 2015, the study was carried out on 82 healthy subjects, 20 of whom aged 0-1, 21 of whom aged 1-3, 20 of whom aged 3-6, and 21 of whom aged 6-12. The inclusion criteria included any kind of skin disease [5]. Twelve skin sites were studied: central forehead, cheek, neck, upper thorax, upper abdomen, waist, volar forearm, dorsal forearm, interscapular region, thigh, calf and dorsum pedis. This study was approved by the Committee of Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University.

Ultrasound imaging

Real-time high-resolution 20 MHz ultrasound imaging equipment (DermaLab Combo, Cortex, Denmark) was used and produces images representing a cross-section of the skin. A standard echographic gel was used as coupling medium between the probe and the skin surface. Minimal pressure was applied to preserve the thickness and echogenicity of the skin. The linear probe was held manually, maintained perpendicular to the skin surface and moved over the skin surface.

Statistics

Thickness and echogenicity measurements of each site were compared. The absolute value referring to the extension of homogeneous amplitude areas of a given image expressed in number of pixels was divided by the skin thickness value of the corresponding image (relative pixel values), in order to exclude variation related to differences in skin thickness, when comparing echogenicity. Means and standard deviations were calculated as basic statistics. The Student's t test and analysis of Variance for the correlation between different parameter values of the samples, as implemented in the SPSS statistical package was used to evaluate the differences between values referring to the skin of children. A p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Skin thickness

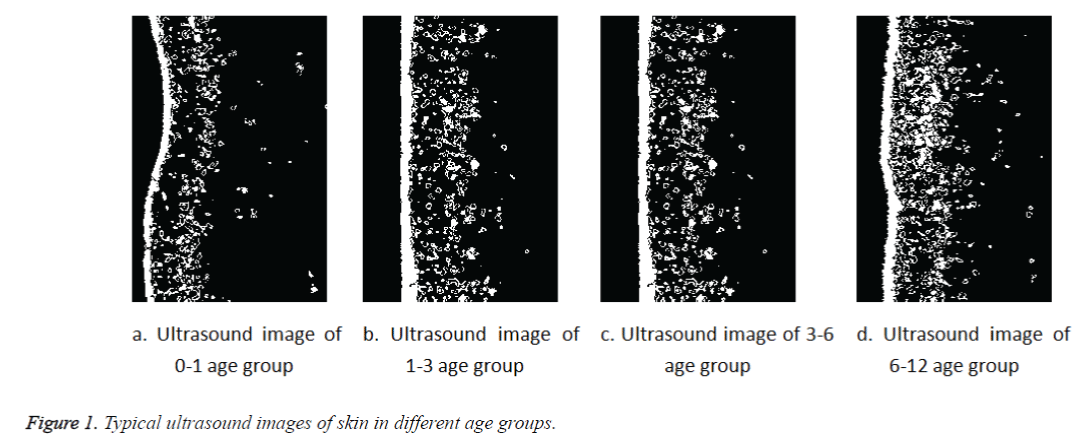

Table 1 shows the results of skin thickness measurements referring to the 4 subgroups of children. In children skin thickness showed a progressive increase with growing age and values referring to the whole group of the younger children were significantly lower with respect to the older children (Figure 1). Table 2 shows a significant statistical of skin thickness differences between all age subgroups, except the age 1-3 years group. Table 3 shows that there are no significant difference between boys and girls in skin thickness. Table 4 shows in Chinese children, the skin thickness of the neck far less than the skin thickness of other sites and the highest thickness values were measured at the interscapular.

| Age group | N | Mean ± SD | 95% Confidence Interval | Lower Value | Upper Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||

| <1 years | 20 | 846.20 ± 76.19 | 802.205 | 890.188 | 723.15 | 961.15 |

| 1-3 years | 21 | 871.25 ± 75.15 | 827.856 | 914.637 | 753.6 | 1054.85 |

| 3-6 years | 20 | 997.46 ± 76.56 | 953.261 | 1041.66 | 901.5 | 1106.6 |

| 6-12years | 21 | 1084.25 ± 95.20 | 1029.28 | 1139.21 | 941.13 | 1239.2 |

| summary | 82 | 949.794 ± 125.37 | 916.215 | 983.361 | 723.15 | 1239.2 |

Table 1. Statistical description of skin thickness (μm) in all age groups.

| <1 years | 1-3 years | 3-6 years | 6-12 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 years | 846.2 | P=0.42 | P=0.00** | P=0.00* |

| 1-3 years | P=0.42 | 871.25 | P=0.00 | P=0.00** |

| 3-6 years | P=0.00** | P=0.00* | 997.46 | P=0.01* |

| 6-12 years | P=0.00** | P=0.00** | P=0.01* | 1084.25 |

Significant statistical differences in all groups, except between the age <1 year group.the age 1-3 years group. *means p<0.05;**means p<0.01

Table 2. Comparison of skin thickness in all age subgroups.

| Gender | N | Mean ± SD | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | 40 | 934.94 ± 144.49 | ||

| Girls | 42 | 927.96 ± 144.49 | ||

| All | 82 | 933.45 ± 133.12 | 0.13 | 0.58 |

No significant differences were found between boys and girls (p>0.05)

Table 3. Comparison of thickness between boys and girls.

| Site | Age group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 years | 1-3 years | 3-6 years | 6-12 years | F | p | |

| Forehead | 845.65 ± 88.04 | 879.14 ± 62.41 | 865.25 ± 64.05 | 889.24 ± 56.11 | 2.81 | 0.3 |

| Cheek | 838.5 ± 102.61 | 819.71 ± 72.55 | 817.15 ± 66.74 | 825.52 ± 64.13 | 0.28 | 0.84 |

| Neck | 723.15 ± 103.84 | 727.24 ± 77.00 | 732.10 ± 72.96 | 749.90 ± 73.35 | 1.51 | 0.22 |

| Upper thorax | 918.25 ± 124.47 | 957.71 ± 98.16 | 836.58 ± 217.95 | 952.71 ± 110.97 | 3.03 | 0.34 |

| Upper abdomen | 989.60 ± 103.56 | 1083.09 ± 111.19 | 1104.75 ± 117.61 | 1179.81 ± 127.73 | 11.14 | 0.00** |

| Waist | 1023.6 ± 121.77 | 1052.38 ± 128.33 | 972.20 ± 160.83 | 1099.24 ± 108.24 | 3.41 | 0.02* |

| Volar forearm | 917.25 ± 143.85 | 840.14 ± 88.62 | 770.90 ± 96.65 | 843.57 ± 92.15 | 6.22 | 0.00** |

| Dorsal forearm | 965.75 ± 150.19 | 985.71±132.64 | 946.45 ± 101.24 | 953.52 ± 89.62 | 3.41 | 0.17 |

| Intersca-pular | 1192.85 ± 95.96 | 1188.95 ± 109.60 | 1167.90 ± 139.15 | 1275.43 ± 110.73 | 3.08 | 0.02* |

| Thigh | 973.80 ± 109.82 | 977.00 ± 130.67 | 906.60 ± 126.43 | 896.31 ± 203.18 | 1.17 | 0.00** |

| Calf | 980.05 ± 151.97 | 953.43 ± 112.47 | 905.8 ± 142.49 | 990.71 ± 132.49 | 1.95 | 0.2 |

| dorsum pedis | 802.15 ± 63.26 | 794.62 ± 58.12 | 801.50 ± 73.29 | 815.71 ± 74.57 | 11.67 | 0.19 |

Table 4. Statistical description of skin full-thickness(μm) in different sites (Upper abdomen, waist, volar forearm and Interscapular region have statistical differences in 4 age subgroups (P<0.05), other sites have no statistical differences in all age subgroups).

Skin thickness was lower in dorsum pedis and cheek areas than in areas of the waist and upper abdomen. Upper abdomen, waist, volar forearm and Interscapular region have statistical differences in 4 age subgroups

Skin echogenicity

Table 5 shows the results of skin echogenicity measurements referring to the 4 subgroups of children. In children skin echogenicity showed a progressive decrease with growing age and values referring to the whole group of the younger children were significantly higher with respect to the older children. Table 6 shows a significant statistical of skin echogenicity differences between all age subgroups, except the age 1-3 years group. Table 7 shows that there are no significant difference between boys and girls in skin echogenicity.

| N | Mean ± SD | 95% Confidence Interval | Lower Value | Upper Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||

| 0-1 years | 20 | 33.59 ± 5.29 | 30.22 | 36.95 | 29.23 | 47.57 |

| 1-3 years | 21 | 31.92 ± 4.99 | 28.74 | 35.09 | 26.4 | 45.02 |

| 3-6 years | 20 | 29.17 ± 3.66 | 26.84 | 31.5 | 24.59 | 38.89 |

| 6-12 years | 21 | 26.44±3.83 | 24.01 | 28.87 | 22.94 | 36.56 |

Table 5. Statistical description of skin echogenicity in all age groups.

| 0-1 years | 1-3 years | 3-6 years | 6-12 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 years | 33.59 | p=0.37 | p=0.02* | p=0.00** |

| 1-3 years | p=0.37 | 31.92 | p=0.14 | p=0.005** |

| 3-6 years | p=0.02* | p=0.14 | 29.17 | p=0.15 |

| 6-12 years | p=0.00** | p=0.005** | p=0.15 | 26.44 |

No statistical differences between 0-1 years group and 1-3 years old group, meanwhile no statistical differences between 1-3 years group and 3-6 years group, the remaining comparison in pairs had statistically different. * means p<0.05; * * means p<0.01.

Table 6. Comparison of skin echogenicity in all age subgroups.

| Gender | N | Mean ± SD | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | 40 | 31.08 ± 4.70 | ||

| Girls | 42 | 30.19 ± 4.29 | ||

| All | 82 | 30.64 ± 4.42 | 0.49 | 0.56 |

No significant differences were found of density between boys and girls(p>0.05)

Table 7. Comparison of echogenicity between boys and girls.

According to the mean echogenicity measurements, the younger children’s skin seems more echogenicity than that of the older children. In the younger children’s skin we observed lower hyporeflecting echo amplitude values and higher hyperechogenic ones, compared to the skin of the older children. And a positive correlation was noticed at these areas between mean echogenicity values and children’s age. In Chinese children, the skin of the forehead, the upper abdomen and the thigh reflects ultrasound far less than the skin of the Volar forearm (Table 8).

| Site | Age group | F | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-1 years | 1-3 years | 3-6 years | 6-12 years | |||

| Forehead | 30.69 ± 7.07 | 26.39 ± 6.59 | 25.07 ± 6.58 | 23.62 ± 4.77 | 2.049 | 0.005** |

| Cheek | 32.19 ± 10.23 | 27.53 ± 7.84 | 26.50 ± 6.13 | 23.91 ± 3.74 | 1.366 | 0.006** |

| Neck | 39.45 ± 9.38 | 34.40 ± 9.46 | 28.21 ± 6.78 | 22.94 ± 4.73 | 2.824 | 0.000** |

| Upper thorax | 38.34 ± 10.37 | 35.02 ± 10.31 | 30.75 ± 8.03 | 27.66 ± 8.01 | 13.196 | 0.003** |

| Upper abdomen | 30.79 ± 6.72 | 27.08 ± 9.62 | 24.59 ± 8.85 | 23.41 ± 4.06 | 0.238 | 0.016* |

| Waist | 37.65 ± 10.18 | 33.95 ± 8.24 | 30.60 ± 10.95 | 28.64 ± 11.34 | 7.124 | 0.036* |

| Volar forearm | 49.95 ± 12.79 | 45.02 ± 14.73 | 38.89 ± 10.39 | 36.55 ± 9.94 | 16.892 | 0.003** |

| Dorsal forearm | 32.60 ± 5.60 | 30.79 ± 6.54 | 27.80 ± 8.45 | 26.27 ± 6.79 | 2.263 | 0.024 |

| Interscapular region | 35.17 ± 7.09 | 29.96 ± 7.64 | 28.85 ± 8.93 | 29.52 ± 5.82 | 26.422 | 0.035* |

| Thigh | 30.70 ± 7.73 | 30.05 ± 6.99 | 29.76 ± 5.49 | 24.55 ± 6.69 | 10.643 | 0.019* |

| Calf | 33.78± 14.39 | 31.91 ± 7.56 | 29.76 ± 5.58 | 25.09 ± 6.93 | 16.175 | 0.025* |

| Dorsipedis | 31.88 ± 9.62 | 30.90± 8.04 | 29.24 ± 8.18 | 25.13± 4.50 | 1.535 | 0.040* |

(the results of skin echogenicity in all age groups were compared are statistical differences (p<0.01). *means p<0.05;**means p<0.01. )

Table 8. Statistical description of skin echogenicity in different sites.

Discussion

Ultrasound skin imaging is a diagnostic technique in which the physical properties of ultrasound are used to examine the skin and skin appendages [6]. It can also use for evaluating dermatoses, besides different skin tumors: morphea, psoriasis, lipodermatosclerosis, skin aging and photodamage, hypertrophic scars and wound healing processes [7-12]. Knowledge of the morphology, thickness and the ultrasound phenomena of healthy skin are always necessary before we can evaluate pathological changes [13].

This study on Chinese children shows that skin thickness and echogenicity is not affected by gender. It is generally believed that the mean skin thicknesses in women were lower than in men [14,15], but maybe some differences in children. Similar to our results, Hofman et al. showed no gender differences in the subcutis prior to puberty [16].

This study on Chinese children shows that skin thickness and echogenicity is affected by age. Our study shows that the skin in the younger children is thinner than in the older children and that variation in skin thickness according to different body sites parallel those of the older children. Moreover, Similar to our results, Stefania et al. showed skin thickness progressively increases with growing age [17]. The thickness of the dermis is primarily responsible for the regional and maturational variation in skin thickness and is mainly determined by its collagen content. A significant increase in total collagen synthesis occurs during the first 3-5 years after birth [18]. With aging, the skin collagen decrease is partly counterbalanced by the overall rearrangement of the dermal collagen network, the accumulation of elastotic material and the increase in water content [18]. The skin thickness values of the healthy Chinese children can help us to evaluate whether or not there are some pathological changes.

It is generally believed that the value referring to epidermis echogenicity in children were lower in respect to those of adults [19]. In this study on Chinese children, we also found that in children skin echogenicity showed a progressive decrease with growing age and values referring to the whole group of the younger children were significantly higher with respect to the older children. Whereas skin thickness shows a gradual increase from birth to adulthood, maturation of the skin leads to variations in the intensity of its echogenicity, depending on the different skin areas. Our observation supports other reports that showed that it appears lower in older children with respect to the younger children. The distribution of skin reflectivity also greatly varies in different phases of life. As we known, the dermis structure is based on the organization of the connective tissue into 2 major regions identified as papillary and reticular dermis. The papillary dermis is readily distinguished from the deeper reticular dermis by the comparatively small size of its collagen bundles and the increased cellularity and density of vascular elements. In the newborn, elastic fibers are located at the periphety of collagen bundles, as in adults, but are smaller and less mature structurally, and contain less elastin matrix [20]. It can explain why the values of skin echogenicity in children were lower than adults.

Our findings illustrate the variability of thickness sonographic findings in healthy skin in respect of anatomical site. This study shows in Chinese children, the skin thickness of the neck far less than the skin thickness of other sites and the highest thickness values were measured at the interscapular. Skin thickness was lower in dorsum pedis and cheek areas than in areas of the waist and upper abdomen. Upper abdomen, waist, volar forearm and Interscapular region have statistical differences in 4 age subgroups. Variations in the thickness of the dermis at different anatomical sites have been shown in numerous studies Similar to our findings.

Our findings also shows that the variability of echogenicity sonographic findings in healthy skin in respect of anatomical site. The intensity of the entry echo is complicated by the tension of the skin. Thus, reference scans in both younger and older subjects showed stronger echogenicity of entry echo and corium when greater tension was applied to the skin during measurement. This might be explained by the fact that the tension leads to a parallel orientation of the fibres and thus to increased reflectivity of individual structures in the skin [21]. So there were different values of echogenicity sonographic findings in healthy skin in respect of different anatomical sites. But we should remember that when ultrasound measurements are compared with the corresponding histological sections, the corium thicknesses determined by ultrasound are smaller. So the values of the skin echogenicity should be Just as a not accurate reference.

To summarize, it may be said that the thickness and echogenicity of the healthy skin can be identified and measured by means of 20 MHz ultrasound which is a painless, low-risk and non-invasive procedure that can easily be performed and provides real-time visual information about benign processes in the skin. In this study, we found that skin thickness and skin echogenicity is not correlated with gender . We also found that whereas skin thickness shows a gradual increase and skin echogenicity shows a gradual decrease with growing age, maturation of the skin leads to variations in the intensity of its echogenicity, depending on the different skin areas. Although this study was conducted in Chinese children, we believe our data may be extrapolated to the general population.

However, some limitations occurred in this research. First of all, few participants were included in this research because of this research is based on children and their guardians usually refused to participate in this research when they were told to sign an informed consents. Although, 10 samples is enough in each group, we think the result will be more credible when the sample size is large enough. Second, this research was based on single center. Consequently, the application of the conclusion in this study will be limited. We need perform a research based on the multi center in the future.

References

- LacarrubbaF,PellacaniG, GurgoneS, Verzì AE, Micali G.Advances in non-invasive techniques as aids to the diagnosis and monitoring of therapeutic response in plaque psoriasis: a review. Int J Dermatol 2015;54: 626-634.

- Bonow RH, Silber JR, Enzmann DR, Beauchamp NJ, Ellenbogen RG, Mourad PD. Towards use of MRI-guided ultrasound for treating cerebral vasospasm. J Ther Ultrasound 2016;4:6.

- Zmudzinska M, Czarnecka-Operacz M, Silny W. Principles of dermatologic ultrasound diagnostics. ActaDermatovenerologicaCroaticaAdc, 2008; 16:126-129.

- Jasaitiene D, Valiukeviciene S, Linkeviciene G, Raisutis R, Jasiuniene E, Kazys R. Principles of high-frequency ultrasonography for investigation of skin pathology. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2011;25:375-382.

- Wortsman X, Wortsmann J, Carreno L, Claudia Morales, Ivo Sazunic, Gregor B. E. Jemec. Sonographic anatomy of the skin appendages and adjacent structures. In: Wortsmann X, Jemec G, editors. Dermatologic ultrasound with clinical and histological correlations. 1st ed Berlin: Springer-Verlag 2013; pp15-35.

- Rallan D, Herland CC. Ultrasound in dermatology – basic principles and applications. ClinExpDermatol 2003;28:632-638.

- Dill-Müller D, Maschke J. Ultrasonography in dermatology. JDDG 2007;5:689-707.

- Aspres N, Egerton IB, Lim AC, Shumack SP. Imaging the skin. Austral J Dermatol 2005;44:19-27.

- Bessonart MN, Macedo N, Carmona C. High resolution B-scan ultrasound of hypertrophic scars. Skin Res Technol 2005;11:185-188.

- Rippon MG, Dyson M, Moodley S, erjee L, Verling W, Weinman J, Wilson P. Wound healing assessment using 20 MHz ultrasound and photography. Skin Res Technol 2003;9:116-121.

- Waller JM, Maibach HI. Age and skin structure and function, a quantitative approach (I): blood flow, pH, thickness and ultrasound echogenicity. Skin Res Technol 2005;11:221-235.

- Hoffmann K, Gerbaulet U, el Gammal S,Altmeyer P. 20 MHz sonography of circumscribed scleroderma. ActaDcrmatoiVenerol l991; 164: 3-16.

- Alexander H, Mtillcr DL. Determining skin thickness with pulsed ultrasound. J Invest Dermatol 1979;72:17-19.

- Kirsch JM, Hanson ME, Gibson JR. The determination of skin thickness using conventional diagnostic ultrasound equipment, ClinExpDcrmatoi 1984:9:280-285.

- Hofman PL, Lawton SA, Peart JM,Holt JA, Jefferies CA, Robinson E, Cutfield WS. An angled insertion technique using 6-mm needles markedly reduces the risk of intramuscular injections in children and adolescents. Diabet Med 2007; 24: 1400-1405.

- Seidenari S, Giusti G, Bertoni L, Magnoni C, Pellacani G.Thickness and Echogenicity of the skin in Children as Assessed by 20-MHz Ultrasound. Dermatology 2000;201:218-222.

- Widdowson EM. Changes in the extracellular compartment of musle and skin during normal and retarded development. BiblNutrDieta 1969;13:60.

- Lasagni C, Seidenari S.Echographic assessment of age-dependent variations of skin thickness. A study on 162 subjects. Skin Res Technol 1995;1:81-85.

- Holbrook KA, Sybert VP. Structural and biochemical properties of the skin of adults, children and newborn infants; in Schachner LA Hansen RC(eds) :Pediatric Dermatology, edn 2. New York, Churchill-Livingstone 1995; 26-70.

- Klaus Hoffmann , Markus Stucker, Thomas Dirschka, Goörtz S, El-Gammal S, Dirting K, Hoffmann A, AltmeyerP.Twenty MHz B-scan sonography for visualization and skin thickness measurement of human skin. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology & Venereology 1994; 3:302-313.

- Dines KA, Sheets PW, Brink JA, Hanke CW, Condra KA, Clendenon JL, Goss SA, Smith DJ, Franklin TD. High-frequency ultrasonic imaging of skin, experimental results. Ultrasonic Imaging 1984;6:408-434.