Research Article - Journal of Nutrition and Human Health (2024) Volume 8, Issue 6

Summer Food Service Program: Perspectives from Program Sponsors

Olivia M Thompson1*, Elizabeth B Symon21Department of Health and Human Performance, College of Population Health, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, United States

2Department of Health and Human Performance, College of Charleston, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, George Street, Charleston, United States

- *Corresponding Author:

- Olivia M Thompson

Department of Health and Human Performance

College of Population Health

The University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, United States

E-mail: OMThompson@salud.unm.edu

Received: 03-Nov-2024, Manuscript No. AAJNHH-23-147164; Editor assigned: 05-Nov-2024, Pre QC No. AAJNHH-23-147164(PQ); Reviewed: 19-Nov-2024, QC No.AAJNHH-23-147164; Revised: 03-Dec-2024, Manuscript No. AAJNHH-23-147164(R); Published: 12-Dec-2024, DOI: 10.35841/aajnhh-8.6.236

Citation: Thompson MO, Symon BE. Summer food service program: Perspectives from program sponsors. J Nutr Hum Health. 2024;8(6):236

Abstract

Background: The Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) was introduced to combat increases in food insecurity rates by providing free meals to children of low-income families over the summer months at approved sites. Objective: The study objective was to strategically develop, with an area foodbank partner, innovative approaches to improve the SFSP within their service area. Methods: The current study was qualitative in nature, utilizing interviews from sponsors within six coastal counties in South Carolina, USA. Sixteen pre-selected interviewees from non-school district community-based organizations, governmental agencies, and school districts participated. Main outcome measures included: barriers to SFSP child participation, barriers to SFSP sponsor participation, and recommendations for SFSP improvement. Key informant interview data were transcribed by a third-party transcription service and then entered into an online software tool that generated word clouds with word frequencies or counts so that major data themes could be deciphered. The software omitted common filler words and presented the 50 most common words found in responses within each word cloud, utilizing an iterative, thematic approach. Two study team members (OT and ES) jointly created a coding structure and independently analyzed each transcript. The team members met frequently to discuss discrepancies and revisions and achieved consensus in their analyses, which were largely indictive. Results: Transportation and lack of program awareness were the main barriers to both child and sponsor participation, and thus program utilization. Other barriers highlighted were: 1) lack of knowledge and training for sponsors/staff; 2) heavy administrative (paperwork) burdens; 3) high start-up costs and the ever-increasing cost of food; 4) lack of proper facilities and equipment including vans/trucks/ buses, storage space, and food storage containers; and 5) compliance with food safety regulations. Sponsors also noted that there was a negative stigma attached to or associated with youth participation in the SFSP or getting free food. Conclusions: Additional research is needed to not only improve the SFSP, but to generate data demonstrating SFSP effectiveness for policymakers and key stakeholders alike

Keywords

Summer food service program, School meals, Food insecurity, Hunger, Childhood obesity.

Introduction

Across the United States (US), over 44 million Americans live in food insecure households, including over 7 million children [1]. Household food insecurity is high, in general, for poor families or those earning annual incomes less than 185% of the federal poverty level (e.g., households earning less than an annual gross income of $57,720 for a family of four) [2]. Additionally, household food insecurity is particularly high for households with children; female (no spouse)-headed households with children; households whereby the reference person identifies as of black race or Hispanic ethnicity; and households located within the southern states (i.e., Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina) [1]. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines food insecurity as “a household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food” [3]. Food insecurity is linked with both poor health outcomes and low academic performance for affected youth [4-6], and it is considered one of the most important public health issues of our time [7]. Preventing and controlling food insecurity (and hunger) has become a main goal for policy makers, health administrators, and community members alike. Federal and state-backed free and reduced school meal programs such as the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) and the School Breakfast Program (SBP) alleviate some of the burden bared by low-income families by providing free or low-cost meals (i.e., breakfast, lunch, and sometimes dinner) during the school year to children of families who fall at or below certain income thresholds [8, 9], now in some states, universally or independent of household income [10]. However, when the school year ends and summer break begins, household-level food insecurity rates rise in part because school meals are no longer provided for free or at a reduced cost [11-13]. The Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) was introduced to combat observed increases in food insecurity rates and help alleviate hunger by providing free meals to children (0-18 years of age) of low-income families over the summer months at approved SFSP sites [14].

Unfortunately, almost since its inception in 196814, the SFSP has been and continues to be underutilized. Recent USDA national trend data, for example, show that between 2001 and 2019 the SFSP provided free meals to about 2.2 million youth in 2001 and to about 2.7 million youth in 2019 on a typical day during the program’s peak month of July (with a fairly steady increase in both number of participants and program sites over the 19-year study period) [15, 16]. In 2001 there were about 17.8 million US students (or 38% of the student population) eligible for either free or reduced-price lunch, and in 2019 there were about 26 million US students (or 52% of the student population) eligible for either free or reduced-price lunch [17]. Taken together, these data suggest that the number of free meals served during summer months was meeting the need for only 12% (in 2001) and 10% (in 2019) of the target audience or of those eligible to receive summers meals and snacks through the SFSP. Participation in the SFSP increased during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic (during years 2020 and 2021) and then normalized (in 2022) [18,19]. Additionally, it is noteworthy to mention that, while SFSP participation data are inconsistently calculated from state to state and year to year [20], program participation (and need) varies considerably by state and across geographic location with the greatest need observed for poor states including those within the deep south where, ironically, summer food aid (i.e., the Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer -EBT- Program) for children has been largely refused [21]. South Carolina is one of the states in the Deep South that has refused to participate in the Summer EBT Program [21], a program that provides $40 per month per child during summer months to low-income families [22], and South Carolina is the focus state of the current study.

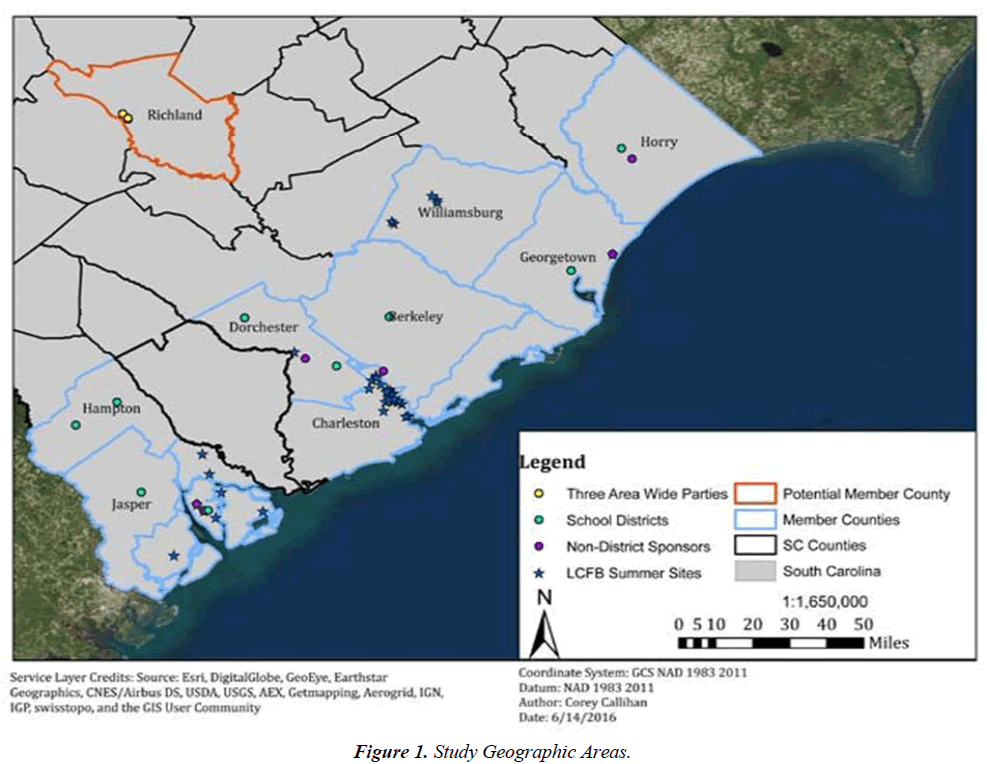

In South Carolina, even though the need for summer meal programming is great, again state law makers have refused to participate in the Summer EBT Program and SFSP utilization in particular remains low. For example, in the Food Research and Action Center’s 2023 Summer Nutrition Status Report, data highlighted indicate that the average daily number of participants in South Carolina’s Summer Lunch programs (i.e., the SFSP or Seamless Summer Option) was only 41,609 students or 9.4% of those eligible in 2021-2022 [23]. Moreover, in South Carolina, the number of SFSP sponsors decreased from 54 in 2021 to 41 in 2022 and the number of SFSP sites decreased from 1,057 in 2021 to 787 in 2022, representing a 24 and 26% respective decrease in the number of sponsors and sites [24, 25]. South Carolina’s Summer Lunch program participation rate was lower than that of the national rate in 2021 and 2022 and during both time periods South Carolina was ranked at or near the bottom half of states for program participation despite being the 5th most food insecure state in the nation1. Reasons for SFSP underutilization in South Carolina and beyond along with solutions and implementation strategies to fix the problem or increase program participation remain unclear. Thus, federal, state, and local agencies and organizations have put out calls for research and program evaluation studies to determine barriers to SFSP participation and recommendations to improve SFSP participation at existing sites and to expand the program’s reach into rural geographic centers. The purpose of the current study was to determine SFSP feasibility across 10 South Carolina counties serviced by a large area food bank. The counties were: Beaufort, Berkeley, Charleston, Colleton, Dorchester, Georgetown, Hampton, Horry, Jasper, and Williamsburg (Figure 1). The overarching study objectives were, in collaboration with community-based key stakeholders, to strategically develop innovative approaches to summer food programming in general and to the SFSP specifically or modify existing summer food programming including the SFSP.

Methodology

Key Informant Interviews

To initiate the current study the investigators issued a letter to 18 pre-selected key informant interviewees or SFSP sponsors identified by the area food bank in order to coordinate in-person or phone interviews that addressed the following questions: How can food banks strategically partner, over a 3-year period and beyond, with organizations within their community to 1) increase access to meals for children and their families during the summer months and 2) increase participation by eligible children in SFSP programming? Each semi-structured, audio-recorded interview was scheduled for 30-45 minutes in length and tailored to question non-school district community-based organizations/partners at large, those who represented governmental agencies and representatives from individual school districts. Non-school district community-based organizations/partners at large were asked 10 overarching questions; while representatives from governmental agencies and individual school districts were asked 7 overarching question each (Table 1). Key informant interview data, which were qualitative in nature, were transcribed by a third-party transcription service and then entered into the online software tool Tag Crowd, which generated word clouds with word frequencies or counts so that major data themes could be deciphered. The software omitted common filler words and presented the 50 most common words found in responses within each word cloud, utilizing an iterative, thematic approach [26], as thematic analysis is useful in examining perspectives of different participants [27]. Two study team members (OT and ES) jointly created a coding structure and independently analyzed each transcript. The team members met frequently to discuss discrepancies and revisions and achieved consensus in their analyses, which were largely indictive.

| Community-Based Organizations (n=5) |

| 1) Currently, what child summer food service programs (SFSPs) exist in your district? |

| 2) In your opinion, would additional child SFSPs benefit students in your district? |

| 3) What have been past efforts in your district in participating in child summer food service program/s? Have you partnered (or are you partnering) with any organizations or agencies? Is this a change since last summer? |

| 4) What do you see as potential barriers or challenges for your district in participating and partnering with agencies in child SFSP? |

| 5) Based on your experience, what do you think is the biggest challenge for a school district sponsor in starting a child SFSP? |

| 6) Ideally, what resources would a sponsor need to start a program in a district where summer food has never been offered? |

| 7) Do you plan on sponsoring/partnering again next summer? |

| 8) Will you add more sites? |

| 9) Would you like help identifying additional sites? |

| 10) From your experience, where could you use additional support to increase the number of children who attend SFSP? |

| Governmental Agencies (n=3) |

| 1) How familiar are you with child summer food service programs (SFSPs)? |

| 2) Currently, what child SFSPs exist in your county/counties? |

| 3) In your opinion, would child SFSPs benefit students in your county/counties? |

| 4) What have been past efforts in your county in participating in child SFSPs? Have you partnered (or are you partnering) with any organizations or agencies? Is this a change since last summer? |

| 5) What do you see as potential barriers or challenges for your county in participating and partnering with agencies in SFSPs? |

| 6) Based on your experience, what do you think is the biggest challenge for a school district sponsor in starting a SFSP? |

| 7) Ideally, what resources would a sponsor need to start a program in a district where summer food has never been offered? |

| School Districts (n=8) |

| 1) How familiar are you with child summer food service programs (SFSPs)? |

| 2) Currently, what child SFSPs exist in your county/counties? |

| 3) In your opinion, would child SFSPs benefit students in your county/counties? |

| 4) What have been past efforts in your county in participating in child SFSPs? Have you partnered (or are you partnering) with any organizations or agencies? Is this a change since last summer? |

| 5) What do you see as potential barriers or challenges for your county in participating and partnering with agencies in SFSPs? |

| 6) Based on your experience, what do you think is the biggest challenge for a school district sponsor in starting a SFSP? |

| 7) Ideally, what resources would a sponsor need to start a program in a district where summer food has never been offered? |

Table 1: Parent/Guardian Characteristics (N=317)

Institutional Review Board

The Institutional Review Board of the College of Charleston approved the study protocol and all participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Key Informant Interviews

Key informants included sponsors from non-school district community-based organizations (n=5), area-wide governmental agencies (n=3), and individual school districts (n=8), totaling 16 key informants (of 18 invited) across six South Carolina counties (i.e., Beaufort, Berkeley, Dorchester, Georgetown, Horry, and Jasper). Key informants discussed ways by which the area food bank could strategically partner, over a 3-year period and beyond, with their particular organization and individual school districts as applicable, to increase access to meals for children and their families during the summer months and increase participation by eligible children in SFSP programming specifically. Answers to overarching questions asked of key informants were collapsed topically as follows: 1) Barries to SFSP child participation; 2) Barriers to SFSP sponsor participation; and 3) Recommendations for SFSP improvement.

Barriers to SFSP Child Participation

The primary barrier to SFSP child participation, according to all 16 key informants, was transportation to and from SFSP sites. For example, one key informant stated: “There’s a big need, you know, how do you get meals to those kids because they may not be near a school or near a park” [28]. Other key informants noted the lack of public transportation available to and from SFSP sites. One key informant stated: “Children can get to school because there’s a public transportation [system] for them to and from school, but then during the summer their parents are working. They’re at home, sitting there all day long, and who’s going to get them to and from these lunch programs?” In addition to transportation barriers, 9 key informants identified lack of SFSP awareness as a key barrier to child participation. One key informant stated: “We can’t assume that people know what benefits are out there, and we can’t assume that people know that they’re eligible for them.” Another key informant noted: “There’s not enough advertisement when it comes to knowing about these services.” The third most commonly discussed barrier to SFSP child participation was the quality of food available at SFSP sites (n=7) [29]. Several key informants discussed the importance of having a “kid friendly menu” or “kid friendly foods” in order for child participation rates to go up. One key informant stated: “We’ve been learning that sponsors who have taken the initiative to have a more inviting menu, their numbers are going up.” With another key informant adding: “We may have sponsors in the areas that are feeding kids, but if the quality of the meal is not meeting certain standards that the kids like, they’re not going to come out in the hot sun to utilize the meal service.” In addition to creating kid friendly menus and foods, key informants stressed the importance of cold versus hot foods and menu planning cycles. Many discussed that kids learn menu cycles and that site sponsors tend to see increased SFSP utilization when hot meals are served. One key informant commented: “The hot foods are far more expensive than the cold foods, but the hot foods are a better drawing card. Kids get tired of cold sandwiches after a while. So, after a couple of years we started mixing it up, so now we do a combination. We do cold foods a couple of day’s week and the other days we do hot foods” [30].

The fourth, fifth, and sixth most commonly discussed barriers to SFSP child participation were noted by 5 key informants each. Five key informants commented, somewhat surprisingly, that a negative association or stigma attached to SFSP sites existed and was becoming an increasingly important barrier to child participation. Several key informants suggested advertising SFSP sites in such a way that all families and kids, regardless of income, associate a site as a positive experience [31]. One key informant explained: “We don’t want there to be a stigma attached that all these kids that go here, they’re poor, and they just need the food. I think that just trying to eliminate any type of stigma that might be attached to it and then making it just a summer experience for the children that they can come participate in and have fun.” Five key informants also identified the time of day that SFSP sites were actually open as being paramount to child participation. One key informant stated: “If you know that your sites are not having big numbers at 8:00 in the morning, you probably don’t need to do it at 8:00 in the morning. You have to look at when your children are going to come out and actually participate.” Several key informants discussed the need for SFSP sites to have extended timeframes, such that child/children could remain at the sites all day while their parent or guardians were at work. One key informant explained: “I would think that the timeframe needs to be a little longer because that way parents really wouldn’t have to worry about what’s going on with their children the whole day while they’re at work.” Another key informant emphasized the need for evening hours at SFSP sites, stating: “My thing, too, is this is all during the day hours. What happens in the evening, you know? They have all maybe morning and afternoon programs, but there’s nothing in the evening at all” [32]. The final most commonly discussed barrier, again also by 5 key informants, to SFSP child participation was a lack of activities provided at SFSP sites as a child participation barrier. Several key informants stressed the need for engaging activities to excite kids and entice them to utilize SFSP sites not just for meals, but also for recreational, educational, and social experiences; with one key informant stating: “They’re not going to get out in the heat and walk because ‘I have my PlayStation. I can sit here all day.’ So, you have to entice them, engage them.” Another key informant commented: “Kids like to have fun, but you want to provide some kind of enrichment if you can, and make it fun, because kids come out when there’s something to do. It can be recreational, but it can be enrichment [activity] as well. Kids like to stay busy” [33].

Barriers to SFSP Sponsor Participation

All of the 16 key informants identified transportation as the biggest barrier to sponsor participation or service not only transporting youth to and from sites, but also transporting food to and from sites pursuant to food safety regulations related to both food travel time and distance. Thinking about a new SFSP site, one key informant commented: “Coming into this area and trying to start a feeding program of any sort, the first thing you would have to think about is how you are going to get your people to and from your site [34]. You know, there aren’t any city buses here like they have in Charleston where you can just get on a bus and go. We don’t have those services. So, if you don’t have a van service connected with your program, you’re basically doomed.” While discussing the issues in meeting food safety regulation when transporting food to SFSP sites, one key informant shared: “One of the greatest challenges we face is because Horry County is spread out so far it’s difficult to be able to cover some areas of the county that I would really like to cover. I do have some sites that are further out that I’m a little uncomfortable in serving hot foods just because I’m afraid that they won’t meet the temperature requirements.” Key informants identified a second major barrier to SFSP service as lack of knowledge and training, specifically with newer SFSPs (n=15). Several key informants commented that there was a severe lack of understanding in what running a SFSP entailed, leaving many newcomers unprepared and overwhelmed. One key informant stated: “With sponsors, what we’re learning is that they don’t prepare themselves well enough. When summer hits, it goes so fast, it’s almost like they’re losing the rest of the whole summer. When they finally get up for air, they don’t want to participate the next year because it was so overwhelming.” Another key informant explained that there was a need for more training for interested parties, stating: “I think earlier training and more in-depth training is the key. This would be overwhelming for a new sponsorship coming in. But, I would say additional training, more in-depth training, a lot more examples of what are the costs, and letting them know some of the challenges they’re going to face. I think somebody who’s never done this before; they’re kind of overwhelmed and blown out of the water.” A third major barrier to SFSP identified by key informants for sites, sponsors, and vendors was the administrative burdens associated with running a SFSP (n=13). Key burdens identified included: financial accountability, meal accountability, keeping up with regulations and requirements, trained and reliable manpower, paperwork, and time commitment. When discussing paperwork and accountability, one key informant stated: “Paperwork is burdensome; I’m not going to lie to you. It took me a lot of my summer just working with Summer Feeding. You have to have the right people in these spots that are going to keep up with all of the paperwork because it’s important to know ‘This is how many I sent out, this is what you got, and now this is what I can claim.’ So, it’s just a check and balance every day.” When discussing all of the administrative burdens as a whole with regard to the level of time that the SFSP required, another key informant explained: “It really takes time. I make it happen, and that’s the only way I can say it. I can’t do any more than I’m doing. I actually counted my time on timesheets a semester ago, and I worked two months more than what I am paid to work. So, you know, we’re talking about 40 days, and that used to be 20 days – didn’t mind that. 20 were not bad, but with the changes in the meal program, and the things I took on to making it work, I can’t get rid of those extra hours” [35].

Ten key informants indicated that financial stability was a major barrier for SFSP sites, sponsors, and vendors specifically for newer programs with startup funding costs and programs stretched thin financially due to changing meal and food safety regulations. One key informant commented: “The biggest thing understands, honestly, you don’t get paid before, you get paid after, and so you’re actually putting the money up front in the beginning.” Another key informant explained the financial burdens felt due to new meal regulations, explaining: “They have changed the regulations [36]. It’s requiring more fruits and vegetables to be served to the kids, so that’s a big difference in the patterns and it certainly affects the costs and the ability of getting everything in their program within the budget. I don’t know if it is something they can sustain with those changes.” Nine key informants identified having proper facilities and equipment as a barrier to SFSP sites, sponsors, and vendors, indicating that, while often difficult to obtain, having an adequate facility size; up-to-code kitchens; storage space; refrigeration; and proper food transportation such as van sizes, coolers, and heat retaining containers (i.e., Cambros) are all needed to run a successful program. One key informant noted: “You know, if you want to serve more than something pre-packaged then you’re going to have the right kind of facility that DHEC would say, ‘Okay, it’s safe to serve meals here.’” One key informant further noted: “Storage space can be hard. We’ll get a whole case of something when we only need a quarter of a case of something. So, the storage, that’s been difficult for us. Freezer and refrigerator space and that sort of thing.” Another key informant stated: “If I’m carrying a hot meal, I have to have the equipment and the van to hold and withstand it hot and keep it hot during that time because you never know what time the kids are actually going to show up.” Finally, eight key informants identified food costs as a major barrier associated with SFSP service. For example, one key informant explained: “Keeping food costs down is a big challenge for me. Milk is an expensive commodity, but we are required to serve milk with every meal. The child does not have to drink it, but we have to serve it. We throw away more milk than anything. We spend a lot on milk, and a lot of it has gone to waste because kids just don’t drink the milk.” Another key informant added: “A major barrier is the cost of food and meal planning. We really can’t serve some of the types of food that we would like to send out, like more fresh fruits and vegetables, because of the cost” [37].

Recommendations for SFSP Improvement

Thirteen key informants identified the needs for programmatic innovation as well as increased advocacy and community involvement as primary recommendations for SFSP improvement. One key informant stated: “It’s about…how do we maximize getting the resources out to the kids, and that’s why I think that we have to be much more creative and innovative about how we do it and more mindful and thoughtful about families so that when we’re thinking about how to do it we really are thinking about the realities of what families are going through.” A key informant added: “When you get more elected officials involved in your area, that drums up a whole other level because when they have that education and knowledge as to what the summer food program is about, then they will be more inclined to assist with getting the kids out there. So, getting the elected officials on the same board and giving them the same knowledge that we’re giving these sites and these sponsors is key.” Several key informants (n=10) mentioned that much of their successes were a result of establishing partnerships with community-based organizations. For example, one key informant stated: “In some areas, where our numbers are high at, we have the sheriff’s department participating. We have the fire departments participating. We have hospitals participating in the summer feeding program. In those areas where you cannot find central locations, getting those kinds of people involved with the summer program is key to getting those kids to really safe places.”

The third most frequently mentioned recommendations for SFSP improvement included the needs for increased outreach and education at not only schools, but also at community-based organizations or area businesses (n=9) and adding additional sites (n=9). One key informant stated: “I think something that would help is our schools helping us to promote summer feeding not just at the schools but in the community and putting out positive messages letting parents know that this is something that can help the entire family.” Another key informant added: “Of course, just because many sites are being served in South Carolina, it still does not represent the full number of children who access free or reduced-price meals during the school year, so we’re probably only reaching maybe a third of those children, and we need to continue to increase the number of sites that make meals available to children to partake in those meals.” Another key informant further explained: “It would benefit us if we could have more sites. Participation is what drives our sites that we have because we are solely based on our funding that comes from participation. If we don’t have the participation this year, then we can’t operate our program next year.” Finally, the fourth most frequently mentioned recommendation for SFSP improvement was the need for utilization of both food trucks and mobile farmer’s markets (n=7). Several key informants discussed that much of South Carolina is rural, thus creating geographic barriers to program participation. One key informant commented: “What we are learning is that there are real rural, rural areas, meaning that there may be a house here, and probably a mile up the street there’s another house. They don’t have a central location for the kids to eat, or a common feeding area. I think the best thing to do in those areas is to have mobile feeding in that area for door-to-door delivery”. Another key informant added: “We kind of bridged that gap this year by going to some of the sites. We rented vans. We rented U-Hauls and actually went into the places kids couldn’t get out of, trailer parks and maybe Section 8 housing. We saw pockets where kids couldn’t get to us, so we went to them and set up tables and fed them there”.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to determine SFSP feasibility within South Carolina counties serviced by a large area foodbank. The overarching study objectives were, in collaboration with community-based key stakeholders, to strategically develop innovative approaches to summer food programming including the SFSP or modify the SFSP along with other existing summer food programs. Key informants (SFSP sponsors) identified transportation as the primary barrier to both child and sponsor participation in the SFSP. Additionally, key informants identified lack of SFSP awareness as the secondary barrier to participation in general and they noted that SFSP site hours or hours of program operation along with site locations were inconvenient for sponsors and families alike. Other barriers highlighted by key informants were: 1) lack of knowledge and training for sponsors/staff; 2) heavy administrative (paperwork) burdens; 3) high start-up costs and the ever-increasing cost of food; 4) lack of proper facilities and equipment including vans/trucks/ buses, storage space, and food storage containers; and 5) compliance with food safety regulations. Importantly, while a secondary theme, several key informants noted that there was a negative stigma attached to or associated with youth participation in the SFSP specifically or getting free food in general.

In addition to barriers for both child and sponsor participation in the SFSP, key informants identified and made several recommendations for program improvement. Primary recommendations were: 1) having a safe and secure site location; 2) serving quality food that youth would actually eat (alternating hot and cold meal or menu cycles); and 3) providing recreational and educational/enrichment activities at sites. Moreover, key informants repeatedly stressed the importance of community outreach and education about summer food programming or SFSP availability as many parents/guardians do not know that the SFSP and other food service opportunities exist; noting that both schools and churches or places or places of worship should be utilized and that parents/guardians should receive information from tangible sources including physical mail, local newspapers, and/or flyers.

Conclusion

While the current study is small and localized, it makes up for its lack in breadth with its depth. Moreover, in line with similar, localized studies and reviews, as well a recent USDA study that examined summer meal programming (i.e., the SFSP and the NSLP Seamless Summer Option) nationally, across 23 states, transportation of youth to and from sites as well as transportation for food delivery to rural sites in particular and lack of summer meal programming awareness were identified as key barriers to child and sponsor SFSP participation, and thus overall program utilization. The combined study findings are timely given the USDA’s recently announced updated guidance for SFSP operations and procedures. The USDA issued three new policy memos and revised two existing ones for: 1) unused reimbursement in the SFSP; 2) best practices for managing unused reimbursement in the SFSP; 3) best practices for determining proximity of SFSP sites; 4) SFSP simplified cost accounting procedures; and 5) SFSP questions and answers – revised. Unused funds (which are not subject to recovery like excess funds are subject to recovery) must be put in a nonprofit food service account and used to improve meal service or program management. Best practices for unused reimbursement in the SFSP include serving high quality foods that incorporate local (and culturally relevant) foods34 and, importantly, sponsors can use unused funds to strengthen the SFSP by improving meal quality, meal service operations (including meal delivery in rural areas, food preparation facilities, and oversight activities that include staff development and training. Best practices for determining proximity of SFSP sites include establishing minimum distances between sites based on population density and the ability to access the sites without transportation. Unfortunately, however, the new USDA guidance does not include dedicated funds for third-party program evaluation and, even if unused funds can be used to improve transportation and lack of awareness barriers, there likely will not be enough money to cover associated costs, particularly given the rising cost of food. In conclusion, dedicated monies for SFSP site evaluations should be provided by the USDA to sponsors to conduct third-party assessments annually, to not only improve the SFSP but to generate data demonstrating SFSP effectiveness and impacts on both community economic outcomes (including the SFSP’s return-on-investment or ROI) and child-level nutritional/health, behavioral, and academic outcomes for dissemination to policymakers, researchers, practitioners (SFSP sponsors), child advocacy groups, parents/guardians, and other key stakeholders.

References

- Rabbitt MP, Hales LJ, Burke MP, et al. Household food security in the United States in 2022. AgEcon. 2023.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Poverty Guidelines for FFY 2025. 2024.

- Norwood JL, Wunderlich GS, editors. Food insecurity and hunger in the United States: An assessment of the measure. National Academies Press. 2006.

- Jyoti DF, Frongillo EA, Jones SJ. Food Insecurity Affects School Children’s Academic Performance, Weight Gain, and Social Skills. J Nutr. 2005;135(12):2831-9.

- Alaimo K, Olson CM, Frongillo Jr EA. Food insufficiency and American school-aged children's cognitive, academic, and psychosocial development. Pediatrics. 2001;108(1):44-53.

- Weinreb L, Wehler C, Perloff J, et al. Hunger: its impact on children’s health and mental health. Pediatrics. 2002;110(4):e41.

- The White House Domestic Policy Council. Biden-Harris Administration National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health. The White House. 2002.

- Song S, Tabares E, Ishdorj A, et al. The Quality of Lunches Brought from Home to School: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr. 2024:100255.

- United States Department of Agriculture. School Breakfast Program. 2024.

- Bylander A, FitzSimons C, Hayes C. The state of healthy school meals for all: California, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, and Vermont Lead the Way. Food Research & Action Center: Washington, DC, USA. 2024.

- Bauer L, Ruffini K, Schanzenbach DW, et al. Food security shouldnt take a summer vacation. 2022.

- Turner L, O’Reilly N, Ralston K, et al. Identifying gaps in the food security safety net: the characteristics and availability of summer nutrition programmes in California, USA. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(10):1824-38.

- Miller DP. Accessibility of summer meals and the food insecurity of low-income households with children. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(11):2079-89.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Summer Food Service Program FAQs. 2024.

- Gordon A, Briefel R, Needels K, et al. Feeding Low-Income Children When School Is Out: The Summer Food Service Program. Final Report. 2023.

- United States Department of Agriculture. USDA’s Summer Food Service Program served 2.7 million children at 47,463 sites in 2019. 2020.

- National Center for Education Statistics. Common Core of Data Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey. 2024.

- Bennett BL, McKee SL, Burkholder K, et al. USDA’s Summer Meals During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Methods Examination of Participants and Non-Participants in 2021. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2024;124(4):495-508.

- Jones JW, Toossi S, Hodges L. The food and nutrition assistance landscape: Fiscal year 2021 annual report. 2022.

- United States Government Accountability Office. Summer Meals: Actions Needed to Improve Participation Estimates and Address Program Challenges (GAO-18-36) Report to Congressional Requesters. 2024.

- Southern Poverty Law Center. Children Face Hunger Across Deep South After States Refuse Summer Food. 2024.

- United States Department of Agriculture. USDA’s Summer Grocery Benefit for Kids. 2024.

- Hess D, Woo N, FitzSimons CW, et al. Hunger Doesn't Take a Vacation: Summer Nutrition Status Report. 2023.

- Jones JW, Toossi S, Hodges L. The food and nutrition assistance landscape: Fiscal year 2021 annual report. 2022.

- Toossi S, Jones JW. The food and nutrition assistance landscape: Fiscal year 2022 annual report. 2023.

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2016.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):1609406917733847.

- Bennett BL, Cohen JF, Andreyeva T, et al. Predictors of Participation in the US Department of Agriculture Summer Meal Programs: An Examination of Outreach Strategies and Meal Distribution Methods During COVID-19. AJPM Focus. 2023;2(4):100124.

- Burkholder K, Bennett BL, McKee SL, et al. Participation in the US Department of Agriculture's Summer Meal Programs: 2019‐2021. J Sch Health. 2024;94(7):647-52.

- Oghaz MH, Rashoka F, Kelley M. Barriers to Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) implementation before and after COVID-19: a qualitative, collective case study. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022;6:113.

- Harper K, Lu SV, Gross J, et al. The impact of waivers on summer meal participation in Maryland. J Sch Health. 2022;92(2):157-66.

- United States Department of Agriculture. USDA Summer Meals Study. 2024.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Unused Reimbursement in the Summer Food Service Program. 2023.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Best Practices for Managing Unused Reimbursement in the Summer Food Service Program. 2023.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Best Practices for Determining Proximity of Sites in the Summer Food Service Program. 2023.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Nationwide Expansion of SFSP Simplified Cost Accounting Procedures - Revised. 2023.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Summer Food Service Program Questions and Answers - Revised. 2023.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref