Research Article - Journal of Nutrition and Human Health (2024) Volume 8, Issue 5

Summer Food Service Program: Perspectives from Parents or Guardians

Olivia Thompson*

Department of Health and Human Performance, College of Population Health, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, United States

- *Corresponding Author:

- Olivia Thompson

Department of Health and Human Performance

College of Population Health

The University of New Mexico

Albuquerque, United States

E-mail: OMThompson@salud.unm.edu

Received: 03-Sep-2024, Manuscript No. AAJNHH-23-147164; Editor assigned: 05-Sep-2024, Pre QC No. AAJNHH-23-147164(PQ); Reviewed: 19-Sep-2024, QC No.AAJNHH-23-147164; Revised: 23-Sep-2024, Manuscript No. AAJNHH-23-147164(R); Published: 01-Oct-2024, DOI: 10.35841/aajnhh-8.5.226

Citation: Thompson O. Summer food service program: Perspectives from parents or guardians. J Nutr Hum Health.2024;8(5):226

Abstract

Objective: The study objective was to develop, with an area foodbank partner, innovative approaches to improve summer food programming (including the Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) in particular) within their service area. Design: Survey and focus group data were collected from parents/guardians eligible to participate in the SFSP within 10 coastal counties in South Carolina, USA. Setting: Quantitative data were collected using an online survey and qualitative data were collected from in-person focus group discussions. Participants: A total of 313 (of 317) parents/guardians answered survey questions that allowed the investigators to classify them as either Low or Very Low Food Secure. An additional 66 parents/guardians agreed to participate in focus group discussions that expanded upon survey data (N=10 focus groups). Results: Less than half of the parent/guardians indicated that they knew of places in the community that served free meals, and over 60% of parents/guardians indicated that providing meals in a safe and secure location was paramount. While less than 40% of parents/guardians indicated that providing free transportation to sites was necessary. Differences were observed by level of food security for providing free transportation to sites with 36.1% of those identified as very low food secure indicating a need, but only 23.3% of those identified as low food secure indicating a need (p=0.02). Transportation was, however, overwhelmingly identified by focus group discussants as the number one barrier to child participation in summer food programming, including the SFSP. Conclusions: Parent/guardian summer food programming key stakeholders have identified barriers to program participation, and they, along with numerous scholars, have made recommendations for improvements that would better optimize participation.

Keywords

Summer food service program, School meals, Food insecurity, Hunger.

Introduction

What does it mean to be poor in the United States? Each year, the United States Government estimates both the number and percentage of people in the United States who are “poor” or “in poverty” based on annual household income levels [1]. If, for example, a person or family’s annual household income falls below a threshold deemed adequate to cover basic living expenses (e.g., an annual gross income of $57,720 for a family of four [2], or the minimum cost of food multiplied by three as food expenditures account for about one-third of household budgets, the individual or family is considered to be poor and may qualify for federal government assistance including food assistance [1]. Before 1960, there were very few federally funded food assistance programs for poor or low-income persons, however, following President Johnson’s declaration of war on poverty in 1964, several federally funded food assistance programs were established and rapidly expanded [1-3]. The Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) was one of such programs. The SFSP was established in 1968 to help ensure that children receive healthful meals during the summer months when school is not in session [4]. Initially, SFSPs operated in geographically poor areas and in areas with large numbers of working women [1] and currently, SFSPs operate in geographically poor areas and have with them flexibilities such as meal delivery for families residing in areas designated as rural [4]. Importantly, the SFSP, like most federally funded anti-poverty initiatives that grew out of 1964 “war on poverty” legislation (i.e., the Economic Opportunity Act), had with it limited state and local government power to influence the way that programs were administered statewide and locally, within counties [3]. Moreover, the direct funding mechanisms associated with Economic Opportunity Act programs including the SFSP allowed the federal government to circumvent de facto exclusions of the poor from designing programs to address their own poverty [3] or get themselves out of poverty and not depend on a governmental system that may or may not continue to exist. For these reasons, many scholars believed (and continue to believe) that Economic Opportunity Act programs designed to combat poverty actually failed to alleviate it or, worse, that the programs were complicit or even instrumental in poverty’s persistence [3].

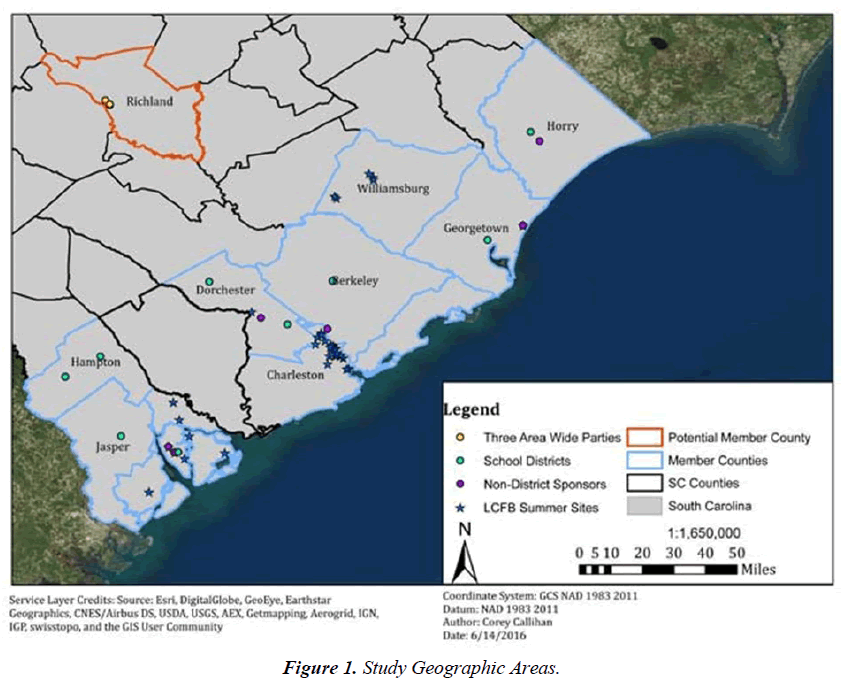

Almost since its inception in 1968, the SFSP has been underutilized [4-6]. Recent United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) national trend data show, for example, that between 2001 and 2019 the SFSP provided free meals to about 2.2 million youth in 2001 and to about 2.7 million youth in 2019 on a typical day during the program’s peak month of July (with a fairly steady increase in both number of participants and program sites over the 19-year study period) [7,8]. In 2001 there were about 17.8 million United States students (or 38% of the student population) eligible for either free or reduced-price lunch, and in 2019 there were about 26 million United States students (or 52% of the student population) eligible for either free or reduced-price lunch [9]. Taken together, these data suggest that the number of free meals served during summer months was meeting the need for only 12% (in 2001) and 10% (in 2019) of the target audience or of those eligible to receive summers meals and snacks through the SFSP. Participation in the SFSP increased during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic (during years 2020 and 2021) and then normalized (in 2022) [10,11]. Additionally, it is noteworthy to mention that, while SFSP participation data are inconsistently calculated from state to state and year to year [12], program participation (and need) varies considerably by state and across geographic location with the greatest need observed for poor states including those within the deep south where, ironically, summer food aid (i.e., the Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer -EBT- Program) for children has been largely refused [13] in spite of several recent studies published demonstrating summer food aid benefits for children and their families [14,15]. Thus, because of this summer food aid rejection, it is even more imperative that strategies demonstrated to optimize SFSP utilization by both program sponsors and eligible children be implemented at congregate (group) and non-congregate (non-group) locations, particularly in southern states where SFSP utilization in particular remains low [16-18]. The purpose of the current study was to determine SFSP feasibility across 10 South Carolina counties serviced by a large area foodbank. The counties were: Beaufort, Berkeley, Charleston, Colleton, Dorchester, Georgetown, Hampton, Horry, Jasper, and Williamsburg (Figure 1). The overarching study objectives were, in collaboration with community-based key stakeholders including parents/guardians, to strategically develop innovative approaches to summer food programming in general and to the SFSP specifically, or to modify existing summer food programs including the SFSP.

Methods

Parent/Guardian Surveys

To initiate the current study, the investigators issued a newsletter to site coordinators participating in the area foodbank’s BackPack Buddies program (i.e., 43 schools in 10 counties, serving 3,164 youth) and School Pantry program (i.e., 31 schools in 10 counties, serving 2,466 youth). Site coordinators were asked to distribute the newsletter to the youth within each program, to share with their parent/guardian for purposes of recruiting the parent/guardian to participate in an online or paper survey. The survey, developed by study investigators in collaboration with staff from the area foodbank, included 35 questions pulled from previously tested and administered surveys (i.e., Share Our Strength’s Summer Meals Survey [19] and the USDA’s Food Security Determinant Survey [20] designed to collect data about parent/guardian’s level of awareness, interest, and need for summer food programming (including the SFSP) in their area. Study investigators cognitively tested individual survey items and the survey as a whole with local, low-income persons who identified as food insecure to ensure that questions asked would be understood by survey respondents. Questions asked were organized topically, into seven distinct areas: 1) summer food struggles; 2) summer food program awareness; 3) summer food program interest; 4) summer food program services, offerings, and incentives; 5) summer food program barriers; 6) summer food program information sources; and 7) demographics. Parent/guardian’s responses were analyzed wholly and by level or degree of food insecurity (i.e., low food security and very low food security) as determined by seven questions from the USDA’s Food Insecurity Determinant Survey [20] modified to account for summer food insecurity specifically. Survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (i.e., frequencies and percentages) and differences between parents/guardians who identified as either low food secure or very low food secure were tested using a Fisher’s Exact Test [21] to determine if observed differences were statistically significant (a two-sided p-value of <.05 was considered to be statistically significant). Of note, preliminary data analyses showed marked differences in survey responses by level of food security status only. The investigators were unable to further test for differences in parent/guardian characteristic variables (i.e., sex, race, ethnicity, employment status, household income, household location, and household designation) between food security status groups because both groups were fairly homogeneous, making data analyses difficult or impossible because of small cell sizes.

Parent/Guardian Focus Group Discussions

To compliment the parent/guardian survey data, the study investigators recruited parents/guardians to participate in focus group discussion sessions comprised of between 6 and 12 parents/guardians each. Prior to focus group participation, each parent/guardian was given a screener survey to determine their level of food security and to ascertain their sex, race, and ethnicity. Each semi-structured, audio-recorded discussion was scheduled for 30-45 minutes in length and tailored to question parents/guardians about: 1) summer feeding or food behavior; 2) summer food struggles; 3) summer food program awareness; 4) summer food program interest; 5) summer food program offerings, services, and incentives; 6) summer food program barriers; and 7) summer food program information. Parent/guardian focus group data, which were qualitative in nature, were transcribed by a third-party transcription service and then entered into the online software tool TagCrowd, which generated word clouds with word frequencies or counts so that major data themes could be deciphered. The software omitted common filler words and presented the 50 most frequently used words found in responses within each word cloud, utilizing an iterative, thematic approach [22] as thematic analysis is useful in examining perspectives of different participants [23]. Two study team members (OT and ES) jointly created a coding structure and independently analyzed each transcript. The team members met frequently to discuss discrepancies and revisions and achieved consensus in their analyses, which were largely indictive.

Results

Parent/Guardian Surveys

Parent/Guardian characteristic data are presented in Table 1. While a total of 317 parents/guardians answered survey questions that allowed the investigators to classify them by their summer food security status, four of the parents/guardians were classified as having high summer food security and were therefore excluded from further analyses. Parents/guardians included (N=313) were classified as having either “very low food security” (n=224) or “low food security” (n=89) during the summer months. The overwhelming majority of survey respondents were women (85.2%) and of Black race (70.3%). Approximately half of the survey respondents reported working full-time (47.6%), but 36.3% reported being unemployed and 12.9% reported working only part-time. The majority of parents/guardians reported earning less than $1,600 per month before tax deductions (56.5%) and only 13.5% reported earning a gross monthly income of $3,500 or more. Most of the parents/guardians reported living in Charleston County (52.7%) and thus “urban” was the primary housing designation identified by survey respondents (40.1%), but importantly, 33.8% reported residing in “rural” designated areas and the remaining parents/guardians reported residing in urban/rural-mixed designated areas (Table 1).

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 29 | 9.1 |

| Female | 270 | 85.2 |

| Missing | 18 | 5.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 28 | 8.8 |

| Not Hispanic | 264 | 83.3 |

| Missing | 25 | 7.9 |

| Race | ||

| Black | 223 | 70.3 |

| White | 60 | 18.6 |

| Other | 9 | 2.8 |

| Missing | 25 | 7.9 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-Time | 151 | 47.6 |

| Part-Time | 41 | 12.9 |

| Unemployed | 115 | 36.3 |

| Missing | 10 | 3.2 |

| Household Income (Monthly) | ||

| Less than $1,600 | 179 | 56.5 |

| Between $1,600 and $3,500 | 79 | 24.9 |

| $3,500 or More | 43 | 13.5 |

| Missing | 16 | 5 |

| Household Location (County) | ||

| Charleston | 167 | 52.7 |

| Other | 143 | 45.1 |

| Missing | 7 | 2.2 |

| Household Designation | ||

| Urban | 127 | 40.1 |

| Rural | 107 | 33.8 |

| Other (Mixed Designation) | 75 | 23.7 |

| Missing | 8 | 2.5 |

| Summer Food Security Status (Household) | ||

| High Food Security | 4 | 1.3 |

| Low Food Security | 89 | 28.1 |

| Very Low Security | 224 | 70.7 |

| Missing | ||

Table 1: Parent/Guardian Characteristics (N=317)

Descriptive data for summer food struggles, summer food program (including the SFSP) awareness, and interest by food security category (i.e., “Low” vs. “Very Low”) are presented in Table 2. In both the low and very low food security categories, less than half of the parent/guardian respondents indicated that they knew of places in the community that served free meals, and there were no statistically significant differences between respondent groups. However, statistically significant differences were observed between respondent groups such that more parents/guardians who identified as very low food secure received a free meal from a community location during the past summer compared to those who identified as low food secure (p=.003). Statistically significant differences were also observed between respondent groups such that more parents/guardians who identified as very low food secure expressed that they were very interested in summer food programming compared to those who identified as low food secure, and less parents/guardians who identified as very low food secure expressed that they were not interested in summer food programming compared to those who identified as low food secure (p<.001) (Table 2).

| Variable | Low % | Very Low % | *p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aware of SFSP/Place where Free Meals Served | NS | ||

| Yes | 41.9 | 46 | |

| No | 58.1 | 54 | |

| Received Free Meals this Past Summer | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 27.2 | 54.8 | |

| No | 72.8 | 45.2 | |

| Level of SFSP Interest | <0.001 | ||

| High | 33.3 | 62.9 | |

| Moderate | 23 | 23.1 | |

| Low or No Interest | 43.7 | 14 |

Table 2: Parent/Guardian Summer Food Struggles and Summer Food Program Awareness and Interest by “Low” vs. “Very Low” Household Summer Food Security Status (N=313)

Descriptive data for parent/guardian preference for summer food program (including the SFSP) services, offerings, and incentives by food security category (i.e., “Low” vs. “Very Low”) are presented in Table 3. For both very low and low food secure respondent groups, between approximately 40 to 60% identified needs at SFSP sites for 1) recreational activities, 2) educational activities, 3) sports/physical activities, 4) serving meals that children were willing to eat, 5) serving meals that were healthy and balanced, 6) serving free meals, and 7) providing opportunities for children to socialize. Over 60% of all respondents indicated that providing meals in a safe location was paramount, while less than 40% of all respondents indicated that providing free transportation to sites and providing meals to adults was necessary. Statistically significant differences were observed by level of food security for providing free transportation to sites with 36.1% of those who identified as very low food secure indicating a need, but only 23.3% of those who identified as low food secure indicating a need (p=.02) (Table 3).

| Variable | Low % | Very Low % | *p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Transportation | 0.02 | ||

| Yes | 23.3 | 36.1 | |

| No | 76.7 | 63.9 | |

| Recreational Activities | NS | ||

| Yes | 51.2 | 44.4 | |

| No | 48.8 | 55.6 | |

| Educational Activities | NS | ||

| Yes | 55.7 | 50 | |

| No | 44.3 | 50 | |

| Sports/Physical Activities | NS | ||

| Yes | 48.3 | 44.2 | |

| No | 51.7 | 55.8 | |

| Meals Child Willing to Eat | NS | ||

| Yes | 58.1 | 52.8 | |

| No | 41.9 | 47.2 | |

| Healthy, Balanced Meals | NS | ||

| Yes | 52.9 | 60.1 | |

| No | 47.1 | 39.9 | |

| Free Meals for All Children | NS | ||

| Yes | 48.3 | 58.8 | |

| No | 51.7 | 41.2 | |

| Safe and Secure Location | NS | ||

| Yes | 67.4 | 66.4 | |

| No | 32.6 | 33.6 | |

| Socialization Opportunities | NS | ||

| Yes | 49.4 | 50.5 | |

| No | 50.6 | 49.5 | |

| Free Meals for Adults | NS | ||

| Yes | 30.6 | 31.3 | |

| No | 69.4 | 68.7 |

Table 3: Parent/Guardian Preferred Summer Food Program Services, Offerings, and Incentives by “Low” vs. “Very Low” Household Summer Food Security Status (N=313)

Descriptive data for summer food program (including the SFSP) barriers by food security category (i.e., “Low” vs. “Very Low”) are presented in Table 4. While the overwhelming majority of parents/guardians indicated that they were interested in summer food programming, statistically significant differences were also observed between respondent groups such that more parents/guardians who identified as very low food secure expressed that they were interested in summer food programming compared to those who identified as low food secure (p=.006). Moreover, along these lines, 24.7% of parents/guardians in the low food security category indicated that their child did not need summer meals, but only 8.5% of parents/guardians in the very low food security category indicated a like response (p <.001). Statistically significant differences were observed between respondent groups such that more parents/guardians who identified as very low food secure expressed that meals were not served at a convenient location and that traveling to summer meal program sites or locations was too much of a hassle, compared to parents/guardians who identified a low food secure (p<.001 and p=.002, respectively). Importantly, over 40% of parents/guardians in both the low and very low food security categories indicated that operational time of day and site proximity were potential summer food program barriers. Afternoon operational hours during both weekdays and weekend days were preferred by parents/guardians in both food security categories, as was having a program site less than 1 mile (or at a maximum between 1 and 10 miles) away from the parent/guardian’s home or place of employment (Table 4).

| Variable | Low % | Very Low % | *p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent/Guardian Not Interested | 0.006 | ||

| Yes | 15.7 | 5.8 | |

| No | 84.3 | 92.4 | |

| Meals Not Served at Convenient Location | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 22.5 | 45 | |

| No | 77.5 | 55 | |

| Program Site/Location Unsafe | NS | ||

| Yes | 15.7 | 21 | |

| No | 84.3 | 79 | |

| Unfamiliar with Program Staff | NS | ||

| Yes | 20.2 | 17 | |

| No | 79.8 | 83 | |

| Children Do Not Need Summer Meals | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 24.7 | 8.5 | |

| No | 75.3 | 91.5 | |

| Child Not Interested | NS | ||

| Yes | 5.6 | 6.7 | |

| No | 94.4 | 93.3 | |

| Traveling to Site/Location is a Hassle | 0.002 | ||

| Yes | 7.9 | 21.9 | |

| No | 92.1 | 78.1 | |

| Do Not Get to Eat as a Family | NS | ||

| Yes | 4.5 | 2.7 | |

| No | 95.5 | 97.3 | |

| Child Previously Participated (Not Satisfied) | NS | ||

| Yes | 4.5 | 3.1 | |

| No | 95.5 | 96.5 | |

| Parent/Guardian Previously Participated (Not Satisfied) | NS | ||

| Yes | 6.7 | 5.4 | |

| No | 93.3 | 94.6 | |

| Preferred Days of Program Operation | NS | ||

| Weekdays Only | 58.4 | 45.9 | |

| Weekend Days Only | 6.5 | 10.1 | |

| Both Weekdays and Weekend Days | 35.1 | 44 | |

| Preferred Hours of Operation (Weekdays) | NS | ||

| Morning | 19.5 | 20.9 | |

| Afternoon | 42.9 | 40 | |

| Evening | 16.9 | 19.3 | |

| Other | 20.8 | 19.5 | |

| Preferred Hours of Operation (Weekend Days) | NS | ||

| Morning | 21.1 | 28.2 | |

| Afternoon | 46.5 | 41.8 | |

| Evening | 11.3 | 14.1 | |

| Other | 21.1 | 16 | |

| Preferred Proximity of Program Site | NS | ||

| Within 1 Mile | 30.6 | 54.1 | |

| Between 1 and 10 Miles | 44.2 | 42 | |

| 10 Miles or More | 5.2 | 3.7 |

Table 4: Parent/Guardian Summer Food Program Barriers by “Low” vs. “Very Low” Household Summer Food Security Status (N=313)

Descriptive data for summer food program (including the SFSP) information sources by food security category (i.e., “Low” vs. “Very Low”) are presented in Table 5. Over 40% of those who identified as very low food secure indicated that their child’s school and a church or place of worship were preferred places to obtain information about summer food programming, while over 40% of those who identified as low food secure indicated that their child’s school, online or on a website, and a church or place of worship were preferred locations. Statistically significant differences were observed by level of food security for obtaining information at a church or place or worship with 54.9% of those who identified as very low food secure indicating a preference and 41.6% of those who identified as low food secure indicating a preference (p=.02). Moreover, between 40 and 60% of those who identified as either very low food secure or low food secure indicated that physical mail or flyers were preferred methods to obtain information about summer food programming with no statistically significant differences between food security categories observed (Table 5).

| Variable | % | % | *p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Where | |||

| Child’s School | NS | ||

| Yes | 64 | 71.4 | |

| No | 36 | 28.6 | |

| Online/Website | NS | ||

| Yes | 41.6 | 33.5 | |

| No | 58.4 | 66.5 | |

| Church/Place of Worship | 0.022 | ||

| Yes | 41.6 | 54.9 | |

| No | 58.4 | 45.1 | |

| Local Library | NS | ||

| Yes | 24.7 | 30.4 | |

| No | 75.3 | 69.6 | |

| WIC/SNAP Office | NS | ||

| Yes | 22.5 | 28.1 | |

| No | 77.5 | 71.9 | |

| Local Community Center | NS | ||

| Yes | 21.3 | 30.4 | |

| No | 78.7 | 69.6 | |

| Local Recreational Center/Pool | 0.05 | ||

| Yes | 10.1 | 28.1 | |

| No | 89.9 | 71.9 | |

| Social Services Office | NS | ||

| Yes | 19.1 | 30.4 | |

| No | 80.9 | 69.6 | |

| Foodbank/Food Pantry/Soup Kitchen | NS | ||

| Yes | 21.3 | 18.3 | |

| No | 78.7 | 81.7 | |

| Community Meetings | 0.017 | ||

| Yes | 28.1 | 16.5 | |

| No | 71.9 | 83.3 | |

| On Public Transportation | NS | ||

| Yes | 7.9 | 9.4 | |

| No | 92.1 | 90.6 | |

| Local Businesses | NS | ||

| Yes | 11.2 | 9.4 | |

| No | 88.8 | 90.6 | |

| Other | NS | ||

| Yes | 4.5 | 4.9 | |

| No | 95.5 | 95.1 | |

| How | |||

| Physical Mail | NS | ||

| Yes | 50.6 | 58 | |

| No | 49.4 | 42 | |

| Flyers | NS | ||

| Yes | 48.3 | 57.6 | |

| No | 51.6 | 42.4 | |

| Online/Website | NS | ||

| Yes | 37.1 | 33 | |

| No | 62.9 | 67 | |

| NS | |||

| Yes | 31.5 | 36.6 | |

| No | 68.5 | 63.4 | |

| Newspaper | NS | ||

| Yes | 32.6 | 35.7 | |

| No | 67.4 | 64.3 | |

| Local News | NS | ||

| Yes | 27 | 33 | |

| No | 73 | 67 | |

| Television | NS | ||

| Yes | 10.1 | 32.1 | |

| No | 89.9 | 67.9 | |

| Radio | NS | ||

| Yes | 28.1 | 29.9 | |

| No | 71.9 | 70.1 | |

| Billboards | NS | ||

| Yes | 28.1 | 12.5 | |

| No | 71.9 | 87.5 | |

| Phone Call | NS | ||

| Yes | 10.1 | 26.8 | |

| No | 89.9 | 73.2 | |

| Ads On Public Transportation | NS | ||

| Yes | 11.2 | 9.8 | |

| No | 88.8 | 90.2 | |

| Text Message | NS | ||

| Yes | 20.2 | 26.3 | |

| No | 79.8 | 73.7 | |

| Home Visit | NS | ||

| Yes | 6.7 | 7.6 | |

| No | 93.3 | 92.4 | |

| Other | NS | ||

| Yes | 6.7 | 3.1 | |

| No | 93.3 | 96.9 | |

Table 5: Parent/Guardian Preferred Summer Food Program Information Sources (Where and How) by “Low” vs.” Very Low” Household Summer Food Security Status (N=313)

Parent/Guardian Focus Group Discussions

Of the 317 parents/guardians who participated in the survey, 66 parents/guardians agreed to participate in focus group discussions that expanded upon survey data (N=10 focus groups). Similarly to the survey, most of the focus group discussants were women (94.0%) and of Black race (82.0%) (Data Not Shown). Moreover, over 40% of the participants reported 1) worrying about running out of food in the past 12 months (45.5%) and 2) that in the past 12 months the food they bought did not last, and they did not have enough money to buy more (42.4%) (Data Not Shown); indicating that about half of parent/guardian discussants were likely experiencing very low food security. Discussants were first asked where their children spent most of their time in the summer, and 45 of the parents/guardians stated that their children spent most of their time at home. Additionally, 45 of the parents/guardians stated that their children also ate meals (in particular lunch) at home during the summer months. Discussants were next asked about summer feeding struggles. When asked whether or not they ran out of food or were worried about running out of food this past summer when kids were not in school, 41 of the parents/guardians gave affirmative answers. When asked if they were worried about running out of food or did run out of food during every month this past summer while kids were not in school, 32 of the parents/guardians gave affirmative answers as well. As one person explained: “I’m used to buying a certain amount of food because they’re at school or aftercare or whatnot, but during the summer it is more of an expense to provide those meals to them.” Another person commented: “Usually you have extra children in your household in the summer, so you always worry about extra food.” Of note, 59 discussants indicated that these summer food worries followed a regular pattern. At the end of each month, when supplemental food assistance program money ran out, the worry intensified. As explained by one of the parents/guardians: “Between the first and tenth of the month is when most of us get our food assistance from the government. If kids are at home, they aren’t just eating 3 times a day; they are eating 6 times a day. They’re not eating every four hours; they’re eating every two hours. That’s not going to last long. So, by the 20th of the month to the end of the month there’s no food.”

Focus group discussants expanded upon their conversation about summer feeding struggles by addressing ways in which they made food last longer when they worried that there may not be enough food. Cutting meal sizes and/or serving nutritious foods but lessening the amount was a strategy mentioned by 47 of the parents/guardians. One person stated: “If you’re used to eating maybe two pieces of sausage, you can only give them one because you didn’t have enough money to by the extra pack.” Sixty-three parents/guardians indicated that they served less nutritious foods. For example, one person explained: “I mean, they are going to have to eat two starches just because the starchier food is the least expensive of the bunch. When the meat is gone, I have to double up on something or whatnot. So, we’ll have spaghetti or whatever or something that’s not their norm. Sometimes you have to double up on the starches, and that, you know, is really not healthy.” When the focus group discussants were short on money and there was not enough food to go around, several of the parents/guardians indicated that they relied on food assistance programs (n=59) and emergency food pantries (n=20). As one person emphasized: “There’d be a week we’d be without food. We’d have to go find food banks, and we’d have to find all of the churches that were giving out food, but they limit you. If you’re getting help from one location, they’ll deny you help at another, but you’ve got a whole week you’re trying to feed your kids, and it makes that kind of hard.”

Mid-way through the focus group discussions, parents/guardians were asked about their level of SFSP awareness. The majority of the parents/guardians did not know where any SFSP sites were located (n=40). One person stated: “Until you came here today, I had no idea there was a summer feeding program available.” Moreover, after discussing their level of SFSP awareness, parents/guardians were asked to think about their family and their interest level in a summer feeding program that would provide free meals for their children during the summer when their children are not in school. All 66 parents/guardians responded as being highly interested. As one person explained: “In the summer it would be very beneficial. That’s five meals a week for the parent or that grandparent that they don’t have to worry about. I believe it would make a tremendous difference.” Before concluding, parent/guardian focus group discussants were asked about what they would like to see in terms of offerings, services, and/or incentives in order for their children to participate in summer food programs. Most of the parents/guardians (n=62) stressed the need for free transportation as many lived in rural areas, with one person explained: “They go to the parks, but it’s just getting the kids to the park because I live out in the middle of nowhere. I don’t have time to take them into town and come back because it’s such a rural area. There’s no real central location.”

The focus group discussions concluded with parents/guardians discussing barriers to summer food program participation. Fifty-nine of the parents/guardians stressed the need for a site location to be safe and secure. One person explained: “If you don’t have enough staff then how are you going to watch all of the kids? I mean, you can’t be there 24/7, but at least know exactly what’s going on, on your grounds. You know what I mean? Because even though it’s an open area, you’ve got to know who’s there and who’s coming in. That’s my biggest worry.” Fifty-seven of the parents/guardians indicated that they would like to see educational at SFSP sites. One person explained: “You don’t want them to just sit there and always be socializing and not still be getting what they need for school. A lot of the kids get out of the habit of school during the summer. Then, when they get back in school then they say, ‘This is new.’ So, if you keep them motivated towards school, not fully but just a little bit, then they say, ‘Okay, this is what I did in school. I remember this.’” Forty-nine of the parents/guardians mentioned offering sports/physical activities in order to keep their children engaged and stimulated throughout the summer while not in school, with one person commenting: “Because of obesity, if you could incorporate exercise that might help.” A second person added: “I think they are just as bored as they are hungry some days. I think having some kind of sports would excite them and give them something teamwise to do during the summer.”

Parents/guardians were asked what would prevent them from allowing their children to participate in a SFSP. The number one barrier, identified by 62 discussants, was lack of transportation. One person explained: “It’s a wide area up here, and that’s why a lot of kids are at home during the summer because it’s too hard to get them to a place and back from a feeding program, especially if you’ve got parents that work.” Another person added: “There has to be transportation. For them to walk in that heat through the street, no sidewalks most of the time, and the traffic lights that aren’t there, it’s dangerous, and it’s not safe for them to do so.” Moreover, and importantly, 59 of the parents/guardians indicated that inconvenient hour of operation was a significant barrier to participation, especially for working parents/guardians. As one person explained: “If it wasn’t somewhere that I could leave my son for the day, then he wouldn’t be able to participate. I can’t drop him off and have to turn around and pick him up in the afternoon during work hours.” Additionally, 57 of the parents/guardians identified stigma, or a negative connotation associated with SFSP sites, as a significant barrier to participation. One person explained: “There’s a social stigma attached to it. Advertise in a way that doesn’t make it feel like a certain group is helped. You know that it’s maybe something available to all, or something.” Another person added: “When you’re telling your kid we’re going to the feeding the needy function and he says that by accident, or says it in conversation with someone, you know, it’s a possibility that it’s going to have a negative comeback, and it’s not right, but it’s the way it is.” Additionally, when parents/guardians were asked where they would like best to learn more about summer feeding programs in their area, the majority of the parents/guardians (n=63) responded that communications from their child’s school such as a flyer, an email, and/or a phone call/text through the school phone blasting system were preferred. Sixty-one of the parents/guardians suggested a local church or place of worship. One person commented: “I think the local church because that’s where most people around here go is church. Everybody is at church.” One parent/guardian stated: “Everyone round here needs some sort of assistance. New people coming into the community who need government assistance should be given the summer feeding information when in the local office. That would get the word out.” Finally, 31 of the parents/guardians recommended the local newspaper as an information source; especially for rural areas where the local newspaper often serves as the main information source. One person stated: “In our area of the county and since we are rural, our most central information source would be the newspapers. I think that would be the most effective way of advertisement in this area”.

Discussion

While a pressing need exists to better elucidate the benefits of summer food programs including the SFSP [24,25], the purpose of the current study was to determine summer food programming (including the SFSP) feasibility across 10 South Carolina counties serviced by a large area foodbank. The overarching study objectives were, in collaboration with community-based key stakeholders including parents/guardians, to strategically develop innovative approaches to summer food programming in general and to the SFSP specifically, or to modify existing summer food programs including the SFSP. Key findings and their implications are discussed below:

Lack of Program Awareness and Interest

In both the low and very low food security categories, less than half of the parent/guardian survey respondents indicated that they knew of places in the community that served free meals, and there were no statistically significant differences between respondent groups. Moreover, parent/guardian focus group discussants identified lack of summer food program or SFSP awareness as a primary barrier to child participation. These findings mirror those from other states [26,27] as well as an earlier South Carolina study whereby over half of the study participants (eligible caregivers who were not participating in the SFSP) had no knowledge of the SFSP [28]. Importantly, while all of the focus group discussants indicated high interest in participating in summer food programs including the SFSP, only about one-third of the low food security survey respondents indicated high interest, but about two-thirds of the very low food security survey respondents indicated high interest. Moreover, over 40% of the parent/guardian survey respondents who identified as very low food secure indicated that their child’s school or a church or place of worship were preferred places to obtain information about summer food programming, while over 40% of the parent/guardian survey respondents who identified as low food secure indicated that their child’s school, online or on a website, and a church or place of worship were preferred locations. Between 40 and 60% of all survey respondents indicated that physical mail or flyers were preferred methods to obtain information about summer food programming. Thus, limited resources may be best spent targeting parents/guardians who identify as having very low food security as opposed to low food security using tangible media distributed by mail or newspapers/flyers, and at physical places such as churches or places of worship and schools.

Lack of Transportation to Sites

Consistent with several recently published studies [29] including the South Carolina study [28], lack of transportation, which is an important social determinant of health [30], was overwhelmingly identified by parent/guardian focus group discussants as the number one barrier to child participation in summer meal programs including the SFSP. Although, collectively, the parent/guardian survey respondents did not suggest that transportation was the number one barrier, statistically significant differences were observed by level of food security for providing free transportation to sites, specifically. Approximately 36% of parents/guardians who identified as very low food secure indicated a transportation need, but only about 23% of parents/guardians who identified as low food secure indicated a need. Thus, again, limited resources may be best spent targeting parents/guardians who (1) identify as having very low food security as opposed to low food security and (2) live in rural areas where public transportation is limited or non-existent and the distance from a summer meal program site to a parent/guardian’s place of employment or home exceeds 1 mile.

Lack of Convenient Site Locations and Hours of Operation

Also consistent with several recently published studies [31], over 40% of parent/guardian survey respondents who identified as very low food secure indicated that meals not being served at a convenient location was a barrier to summer meal program including SFSP participation, but only about 23% of those who identified as low food secure indicated a like response. Over 40% of all survey respondents indicated that both operational time of day and site proximity were potential summer food program barriers. Afternoon operational hours during both weekdays and weekend days were preferred by parents/guardians in both food security categories, as was having a program site less than 1 mile (or at a maximum between 1 and 10 miles with less than 1 mile preferred) away from the parent/guardian’s home or place of employment. Parent/guardian focus group discussants echoed survey respondents’ sentiments, thereby reinforcing the need to have program sites open during afternoon hours at sites convenient to program participants, offering grab-and-go meals, and delivering meals to rural participants. Importantly, both survey respondents and focus group discussants stressed that program sites must be safe and secure for their child to participate – parents/guardians discussed that not being familiar with program staff made a site feel unsafe and unsecure and that a referral from a friend or family member made a site feel safe and secure even if the parent/guardian was not familiar with program staff.

Program Site Enhancements

While secondary to lack of summer meal program awareness, transportation, and convenient site locations and hours of operation; both survey respondents and focus group discussants identified enhancements believed to prevent summer weight-gain [32] and summer learning loss among youth as innovative ways to increase program participation. Between approximately 40 to 60% of survey respondents identified each of the following as an enhancement that would likely increase program participation: 1) recreational activities, 2) educational activities, 3) sports/physical activities, 4) serving meals that children were willing to eat, 5) serving meals that were healthy and balanced, 6) serving free meals, and 7) providing opportunities for children to socialize. Furthermore, all of the parents/guardians who participated in focus group discussions indicated that they were interested in participating in summer meal programming including the SFSP, and they stressed that free summer meals would aid in reducing household summer expenses, help provide healthier meals for their children (specifically, at the end of the month), and provide engagement/enrichment opportunities for their children.

Conclusion

The SFSP, like most federally funded anti-poverty initiatives that grew out of 1964 “war on poverty” legislation had with it limited state and local government power to influence the way that programs were administered statewide and locally, within counties. Moreover, the associated direct funding mechanisms allowed the federal government to circumvent de facto exclusions of the poor from designing programs

References

- Tiehen L, Jolliffe D, Gunderson C. Alleviating poverty in the United States: The critical role of SNAP benefits. USDA. 2012;132:1-30.

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. Federal Poverty Guidelines for FFY 2025. 2024.

- Bailey MJ, Duquette NJ. How Johnson fought the war on poverty: The economics and politics of funding at the office of economic opportunity. J Econ Hist. 2014;74(2):351-88.

- United States Department of Agriculture. Summer Food Service Program FAQs. 2024.

- Hopkins LC, Webster A, Kennel J, et al. Plate Waste in USDA Summer Food Service Program Open Sites: Results from the Project SWEAT Sub-Study. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2023;18(5):699-712.

- United States Department of Agriculture. USDA Summer Meals Study.2024.

- Gordon A, Briefel R, Needels K, et al. Feeding Low-Income Children When School Is Out: The Summer Food Service Program. Final Report. ERIC. 2023.

- United States Department of Agriculture. USDA’s Summer Food Service Program served 2.7 million children at 47,463 sites in 2019. 2024.

- National Center for Education Statistics. Common Core of Data Public Elementary/Secondary School Universe Survey. 2024.

- Bennett BL, McKee SL, Burkholder K, et al. USDA’s Summer Meals During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Methods Examination of Participants and Non-Participants in 2021. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2024;124(4):495-508.

- Jones JW, Toossi S, Hodges L. The food and nutrition assistance landscape: Fiscal year 2021 annual report. AgEcon Search. 2022.

- United States Government Accountability Office. Summer Meals: Actions Needed to Improve Participation Estimates and Address Program Challenges (GAO-18-36) Report to Congressional Requesters. 2024.

- Southern Poverty Law Center. Children Face Hunger Across Deep South After States Refuse Summer Food. 2024.

- Turner L, Calvert HG. The academic, behavioral, and health influence of summer child nutrition programs: A narrative review and proposed research and policy agenda. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119(6):972-83.

- Kingshipp BJ, Scinto-Madonich S, Bahnfleth C, et al. USDA-funded summer feeding programs and key child health outcomes of public health importance: a rapid review. USDA. 2023.

- Hess D, Woo N, FitzSimons CW, Parker L, Weill J. Hunger Doesn't Take a Vacation: Summer Nutrition Status Report. 2003.

- Jones JW, Toossi S, Hodges L. The food and nutrition assistance landscape: Fiscal year 2021 annual report. AgEcon Search. 2022.

- Toossi S, Jones JW. The food and nutrition assistance landscape: Fiscal year 2022 annual report. AgEcon Search. 2023.

- Sims K, Caldwell K. Summer Nutrition Insights: 2014 National Summer Meals Sponsor Survey Findings. 2024.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Survey Tools. 2024.

- Clapham C, Nicholson J, Nicholson JR. The concise Oxford dictionary of mathematics. Oxford University Press, USA. 2014.

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE. 2021:1-440.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, et al. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):1609406917733847.

- Soldavini J, Franckle RL, Dunn C, et al. Strengthening the Impact of USDA’s Child Nutrition Summer Feeding Programs During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Durham, NC: Healthy Eating Research. 2021.

- Brown A. Who takes up a free lunch? Summer Food Service Program availability and household grocery food spending. Food Policy. 2024;123:102553.

- Kannam A, Wilson NL, Chomitz VR, et al. Perceived benefits and barriers to free summer meal participation among parents in New York City. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2019;51(8):976-84.

- Bennett BL, Gans KM, Burkholder K, et al. Distributing summer meals during a pandemic: challenges and innovations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6):3167.

- Draper C, Jones S. Summer Feeding Program Utilization in the Midlands of South Carolina (Report Brief). Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina. 2014.

- Oghaz MH, Rashoka F, Kelley M. Barriers to Summer Food Service Program (SFSP) implementation before and after COVID-19: a qualitative, collective case study. Curr Dev Nutr. 2022;6:113.

- Starbird LE, DiMaina C, Sun CA, et al. A systematic review of interventions to minimize transportation barriers among people with chronic diseases. J Community Health. 2019;44:400-11.

- Whaley JE, Lee K, Butler RA. Operational Efficiency of School-Based vs. Community-Based Summer Food Service Programs. J Food Nutr Res. 2019;7(3):237-43.

- Evans EW, Bond DS, Pierre DF, et al. Promoting health and activity in the summer trial: implementation and outcomes of a pilot study. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:87-92.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref