Case Report - Journal of Invasive and Non-Invasive Cardiology (2018) Volume 1, Issue 1

Successful embolization of a large pulmonary arteriovenous malformation in a symptomatic teenager from a developing cardiac program.

Sulaiman Lubega1, John P. Breinholt2*1Department of Cardiology, Mulago Hospital, Kampala, Uganda

2Department of Pediatrics, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, Texas, United States

- Corresponding Author:

- John P. Breinholt

Department of Pediatrics

University of Texas Health Science Center

6410 Fannin Street Suite 425, Houston, Texas, United States

Tel: +1-713-500-5737

E-mail: john.p.breinholt@uth.tmc.edu

Accepted date: March 14, 2018

Citation: Lubega S, Breinholt JP. Successful embolization of a large pulmonary arteriovenous malformation in a symptomatic teenager from a developing cardiac program. J Invasive Noninvasive Cardiol. 2018;1(1):10-13.

DOI: 10.35841/invasive-cardiology.1.1.10-13

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Invasive and Non-Invasive CardiologyAbstract

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations are a rare entity in children, and can cause significant morbidity. Device embolization has become the intervention of choice over the past 2 decades as more sophisticated devices have become available. We present an adolescent with a single, large arteriovenous malformation diagnosed and treated as part of an international medical mission in Kampala, Uganda, highlighting the atypical diseases encountered in developing countries and treatment modalities that can be employed.

Keywords

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformation, Cyanosis, Interventional cardiology.

Introduction

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations are a rare entity in children, and can cause significant morbidity. In children, they have been described in the setting of severe liver disease, after surgical palliation with a cavopulmonary shunt where hepatic venous blood is excluded from the pulmonary circulation, or associated with other systemic disease. Clinical manifestations typically occur in the fourth to sixth decades, and are present in greater than 70% of patients [1-4]. Common symptoms include exertional dyspnea, fatigue and cyanosis. More serious complications include stroke or transient ischemic attack (11-55%), seizures (5-15%), brain abscess (5-25%), hemoptysis or hemothorax in up to 18%, and a higher incidence of migraine headaches [1-8].

Device embolization has become the intervention of choice over the past 2 decades as more sophisticated devices have become available. Detachable balloons were initially preferred, but were largely replaced by coil embolization in later years. More recently, the development of the Amplatzer Vascular Plugs (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, Minnesota) have made device embolization even more favourable [1,2,4,5,9-16]. While pulmonary arteriovenous malformations can occur as a single entity, they are frequently encountered as multiple lesions, often affecting only one lung, and can be associated with systemic diseases such as hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia [17]. We present an adolescent with a single, large arteriovenous malformation diagnosed and treated as part of an international medical mission in Kampala, Uganda.

Case Report

A 13-year-old Ugandan male was growing and developing normally until the age of 7 years when he developed gradually worsening exercise intolerance, exertional dyspnea, central cyanosis, and scleral injection. Subsequently he developed weight loss, dizziness, palpitations, digital clubbing, and bowing of both lower and upper limbs. He intermittently reported knee and elbow arthralgias. He had no history of cough, chest pain, edema or syncope. Laboratory data at presentation included polycythemia (Hemoglobin 28 mg/dl) for which he would undergo phlebotomy five times per year to aide with severe headaches. A local hematologist would later initiate hydroxyurea, aspirin and esomeprazole therapy. While these treatments reduced the need for phlebotomy, symptoms did not abate.

At 12 years of age he was evaluated at the regional heart institute. He could not walk more than 50 m and had fallen behind academically because he had insufficient energy to attend school which was across the street from his residence. Imaging studies included a chest radiograph that exhibited a prominent right hilum, but was otherwise unremarkable. An echocardiogram demonstrated mildly dilated left heart chambers with a small patent foramen ovale with left to right shunting. Biventricular function was normal, and there was no septal wall flattening and the tricuspid regurgitation jet suggested normal right ventricular systolic pressure. Due to cyanosis and digital clubbing, a right to left shunt was suspected, but was not identified by ultrasound imaging. His oxygen saturation was 68-70% on room air.

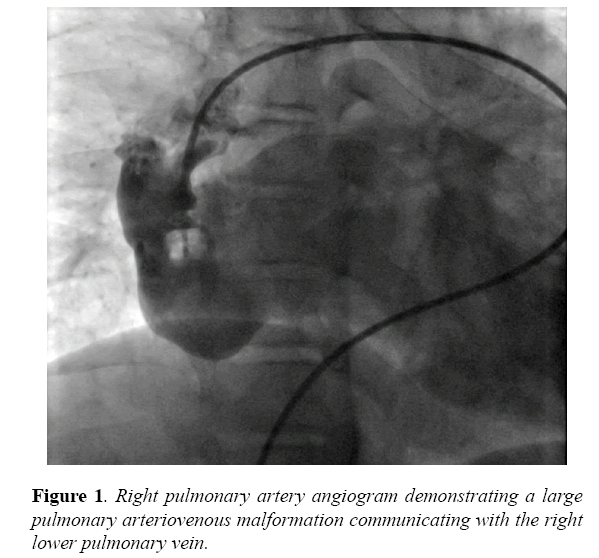

A new catheterization laboratory was installed in the region and he was referred for diagnostic catheterization at 13 years. His height was 156 cm and weight was 44 kg. A bubble contrast echocardiogram with injection in a left arm IV was performed prior to the catheterization that demonstrated rapid filling of contrast to the right atrium and subsequent left atrium within 3 beats. At catheterization, a 7 French balloon wedge catheter (Arrow International Inc., Reading, Pennsylvania) was introduced and directed to the right pulmonary artery where it easily passed into the left atrium. Pulmonary artery pressures were normal, with systolic pressures of 18 mmHg. Left atrial pressure was mildly elevated with a mean pressure of 12 mmHg. Angiography demonstrated a single large connection between the right lower pulmonary artery and the right lower pulmonary vein (Figure 1).

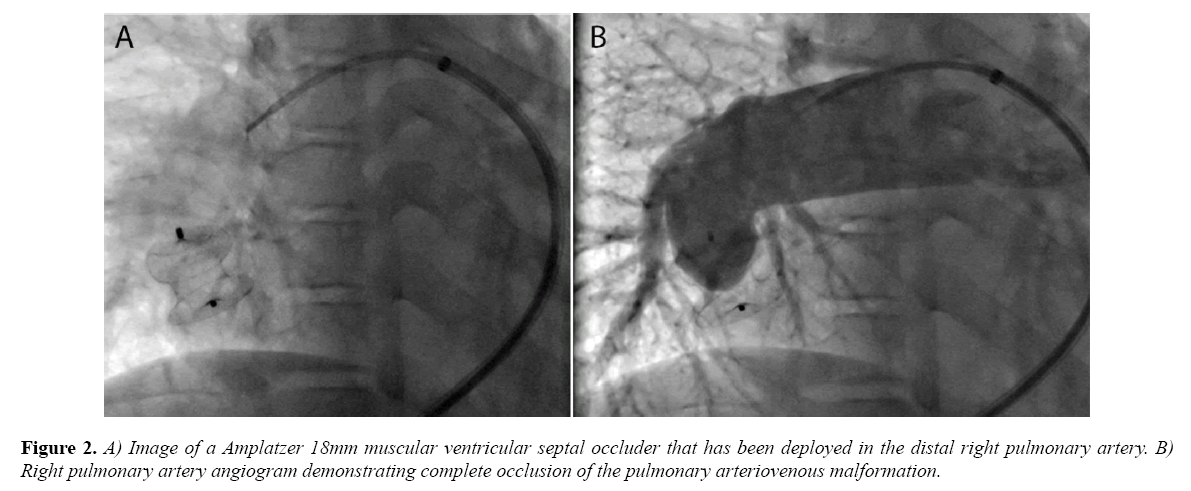

There was no evidence of other arteriovenous malformations on the right or left. The narrowest diameter of the communication measured approximately 16 mm. After placing an 8 French long sheath (Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, Indiana) in the distal right pulmonary artery, an 18 mm Amplatzer muscular ventricular septal defect occluder (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, Minnesota) was deployed across the narrowest area of the arteriovenous malformation (Figure 2A).

There was no significant change in pressure measurements following device release. Follow-up angiography demonstrated complete occlusion of the defect and no evidence of obstruction to surrounding pulmonary artery branches or pulmonary venous return (Figure 2B).

The morning following the procedure, the patient appeared pink and oxygen saturation was 96% on room air. Chest radiograph demonstrated the device in stable position. Echocardiography demonstrated normal biventricular function with normal septal wall motion. The PFO continued to demonstrate left to right shunting. Within one week of the procedure, the patient reported improved exercise tolerance. Three months following the procedure, the patient’s father reported that his son had normal exercise tolerance, however, they would not return to Kampala for follow-up diagnostic evaluation.

Discussion

This report describes the successful embolization of a single, large pulmonary arteriovenous malformation connecting the right lower pulmonary artery to the right lower pulmonary vein. The patient did not have an associated disease process, and had become significantly symptomatic prior to intervention. Importantly, this adolescent had presented with initial symptoms 6 years prior to intervention and had undergone extensive evaluation and medical therapy without definitive diagnosis. Even with a presumptive diagnosis, or sufficient concern to request an invasive diagnostic procedure, limitations within the country required a delay until the adequate facility was constructed to allow the investigation to take place. Additional limitations to intervention include the paucity of physicians trained to perform them as well as insufficient resources to provide the needed devices for the procedure.

Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations are rare, but well documented entities, albeit less common in children in the absence of other diseases or congenital heart disease. This case is unique to the degree of symptoms present at the time of diagnosis. The literature largely describes the setting of multiple pulmonary arteriovenous malformations that require occlusion with multiple small devices. In this case, a single large device was required. While a large type 2 Amplatzer vascular plug (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, Minnesota) may have been sufficient, utilizing available resources was required. The ventricular septal defect occluder (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, Minnesota) provided an important anchoring mechanism with the retention discs, and a device waist of sufficient size to fill the defect.

Conclusion

This case highlights an example of flexibility and use of devices designed for other specific purposes. Moreover, where resources are limited, utilizing any device available is a necessary compromise to the best, or intended, device to solve uncommon and unanticipated cardiac conditions. For interventional cardiologists who participate in medical missionary work, or spend time in regions of limited resources, deciding what equipment to bring presents significant, logistic challenges. A mission trip designed to focus on valvuloplasty procedures, as was the one with this case, could obviate the need to bring multiple devices and delivery systems of multiple sizes. However, as is frequently encountered, such circumstances arise and unscheduled needs occur. As more catheterization laboratories are built in these regions, there may be a demand for creating a “tool kit” to assist interventional cardiologists in preparing for the unexpected. Moreover, it will be important for these cardiologists to prepare to train local physicians as these facilities strive to serve their communities.

References

- Mager JJ, Overtoom TT, Blauw H, et al. Embolotherapy of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: Long-term results in 112 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:451-6.

- Pollak JS, Saluja S, Thabet A, et al. Clinical and anatomic outcomes after embolotherapy of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:35-44.

- Swanson KL, Prakash UB, Stanson AW. Pulmonary arteriovenous fistulas: Mayo clinic experience, 1982-1997. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:671-80.

- White RI Jr, Lynch-Nyhan A, Terry P, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: Techniques and long-term outcome of embolotherapy. Radiology. 1988;169:663-9.

- Gupta P, Mordin C, Curtis J, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: Effect of embolization on right-to-left shunt, hypoxemia, and exercise tolerance in 66 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:347-55.

- Moussouttas M, Fayad P, Rosenblatt M, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: Cerebral ischemia and neurologic manifestations. Neurology. 2000;55:959-64.

- Shovlin CL, Jackson JE, Bamford KB, et al. Primary determinants of ischaemic stroke/brain abscess risks are independent of severity of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Thorax. 2008;63:259-66.

- Burke CM, Safai C, Nelson DP, et al. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: A critical update. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:334-9.

- Andersen PE, Kjeldsen AD. Long-term follow-up after embolization of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations with detachable silicone balloons. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:569-74.

- Hart JL, Aldin Z, Braude P, et al. Embolization of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations using the amplatzer vascular plug: Successful treatment of 69 consecutive patients. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:2663-70.

- Lee DW, White RI Jr, Egglin TK, et al. Embolotherapy of large pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: Long-term results. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64:930-9.

- Letourneau-Guillon L, Faughnan ME, Soulez G, et al. Embolization of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations with amplatzer vascular plugs: Safety and midterm effectiveness. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:649-56.

- Prasad V, Chan RP, Faughnan ME. Embolotherapy of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: Efficacy of platinum versus stainless steel coils. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:153-60.

- Saluja S, Sitko I, Lee DW, et al. Embolotherapy of pulmonary arteriovenous malformations with detachable balloons: Long-term durability and efficacy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:883-9.

- Berman W Jr, Fripp RR, Raisher BD, et al. Transcatheter occlusion of large pulmonary arteriovenous fistula. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;51:220-2.

- Grady RM, Sharkey AM, Bridges ND. Transcatheter coil embolisation of a pulmonary arteriovenous malformation in a neonate. Br Heart J. 1994;71:370-1.

- Bayrak-Toydemir P, McDonald J, Markewitz B, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlation in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Mutations and manifestations. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:463-70.