Research Article - Biomedical Research (2018) Volume 29, Issue 21

Study of the attitude of Bulgarian society towards surrogacy.

Desislava Bakova1, Delyana Davcheva2, Anna Mihaylova3, Penka Petleshkova4*, Snejana Dragusheva5, Biyanka Tornyova1 and Maria Semerdjieva1

1Department of Health Care Management, Medical University of Plovdiv, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

2Department of Clinical Laboratory, Medical University of Plovdiv, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

3Medical College, Medical University of Plovdiv, Bulgaria

4Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical University of Plovdiv, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

5Department of Nursing Care, Faculty of Public Health, Medical University, Plovdiv, Bulgaria

- *Corresponding Author:

- Penka Petleshkova

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Medical University of Plovdiv

Bulgaria

Accepted date: November 30, 2018

DOI: 10.4066/biomedicalresearch.29-18-1156

Visit for more related articles at Biomedical ResearchAbstract

Aim: The dynamic and rapid development of medicine and assisted reproductive technology (ART), in particular, has opened up a whole new range of opportunities for infertile couples worldwide. In the resent years, the number of couples with reproductive problems and infertility in Bulgaria has sharply increased. For some of them surrogacy is the only chance for having a child. This calls for the introduction of new legislative, regulatory provisions concerning surrogacy agreements. This article provides an overview of the current attitudes in Bulgarian society as regards surrogate motherhood and its legalization.

Materials and methods: 256 respondents, aged from 20 to 61 y (mean 36.26 ± 0.55), of whom 48.7% men and 51.3% women, took part in the anonymous survey. The questions in the survey are related to ethical, legal and social aspects of surrogacy.

Results: The findings revealed a positive attitude towards surrogacy as a means of assisted reproduction, with 79.2% of all respondents sharing the opinion that it is mandatory to legalize and regularize surrogacy in Bulgaria.

Conclusions: These results are important because they demonstrate generally tolerant attitudes in Bulgarian society towards surrogacy. The introduction of adequate laws and regulations will significantly facilitate assisted reproduction, and will, to a great extent, curb the some inconvenience of surrogacy whilst ensuring the protection of the rights of both the surrogate mother and the commissioning couple.

Keywords

Surrogacy, Legal issues, Ethical aspects

Introduction

The problem of human reproduction embodies interpersonal relationships at moral, religious, legal, social-political and scientific level. The latest biomedical technologies provide a bridge between modern biomedicine and the value of human life. Scientific progress and technological advancements aim at ‘facilitating’ human existence. It is in technologies ensuring the reproduction of human life that the value of life is strongly expressed. Modern forms of medical intervention in the reproductive capacity of man became widespread in the 20th century and were implemented against the background of principal changes in the moral assessment and legal status. Attitudes to these forms of intervention are connected with different systems of values, cultural and religious traditions.

Many countries have undertaken governmental inquiries to propose legal conditions under which ART may be acceptable, and to set limits beyond which their use is unacceptable on ethical grounds. Similar inquiries have been conducted by the World Health Organization Guidelines for Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) [1], the Council of Europe and various medical societies to determine the conditions and limits of acceptable professional practice and scientific research, and respect for the dignity of the human being etc. [2,3].

In this century of a threat of shortage of resources on a global scale due to the progressively growing number of the population, Bulgaria is faced with a severe and constantly deepening demographic crisis-low birth rate, high rate of emigration of members of the active population, ageing population and the alarming statistics of approximately 2,90,000 couples in Bulgaria trying to cope with the problem of infertility. Being unable to conceive in a natural way, many couples resort to the new reproductive technologies. The personal experiences of hundreds of thousands of couples in their efforts to conceive a child sound alike in all languages, and their inviolable right of personal choice and complete life justify the implementation of assisted reproductive technologies and surrogacy, in particular. The issue of surrogacy has received growing publicity in Bulgaria in recent years. In the past decade, the surrogate industry has increased, and the countries with legalized surrogacy have been striving to boost their activity and development using all kinds of marketing tools and mechanisms [4-6]. This fact puts on the agenda a series of legal and ethical dilemmas, as well as the attempt to evaluate the economic and operational potential of this internationally unregulated activity. There are risks for children carried by surrogate mothers becoming involuntary and probably affected accomplices in the procedure, are also subject of debates. These ethical aspects of surrogacy call for strict international legal regulations in this ever so sensitive for society area of human reproduction in complete compliance with the local culture, traditions and public opinion. Given the complex social, ethical and legal issues involved, surrogacy continues to raise debate worldwide and fuel calls for increased domestic provision in developed countries [7].

Nature of Surrogate Motherhood

Surrogacy is one of the new methods of assisted reproduction which is used as the only practical way for solving the problem of infertility in some couples [8]. The term surrogacy refers to the process in which a woman carries and gives birth to the baby for another per-son or couple, who are called the intended parent [9].

Тhere are two types of surrogate arrangements: traditional and gestational surrogacy. Traditional surrogacy, also known as genetic surrogacy, refers to the process in which an embryo is created from the sperm of the intended father and egg of the gestational surrogate, the process usually being carried out through artificial insemination [10]. Gestational surrogacy, in which the gestating mother receives an embryo formed in vitro from the gametes of the intended parents, differs from surrogate motherhood in that the gestator is not genetically related to the baby she carries [11].

The first documented, successful, gestational surrogacy was done by Utian et al. [12]. Depending on the country, there is specific legislation for each type of surrogacy arrangement, just one or both types of arrangement being legal in some cases [13].

Legal Regulations of Surrogacy

There is still debate for the legal, social and ethical aspects of surrogacy almost all over the world [14-16].

Surrogacy is legally regulated by the Brussels declaration of the World Medical Association of 1985, having the validity of an international law. The said act also declares surrogacy for commercial purposes illegal. In 2006 the World Medical Association (WMA) adopted the following framework regarding surrogate motherhood: “Where a woman is unable, for medical reasons, to carry a child to term, surrogacy may be used to overcome childlessness, unless prohibited by national law or the ethical rules of the National Medical Association or other relevant organization. Where surrogacy is practiced, great care must be taken to protect the interests of all parties involved” [17].

The first law in the world regulating surrogacy was the Surrogacy Arrangements Act in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland [18]. Non-commercial surrogacy has been legal in the UK since 1985 [19].

In Canada, GC arrangements are regulated under the Assisted Human Reproduction Act of Canada (AHRAC). The AHRAC prohibits direct payments to gestational carriers, but allows reasonable reimbursements for pregnancy-related expenses [20].

In 1991 the Ministries of Health and of Justice in Israel nominated a public committee to inspect the social, ethical, religious and legal aspects of assisted reproduction [21]. Israel is a country in which medically assisted reproduction is practiced extensively with almost unlimited public funding [22]. Courts recognize a constitutional right to parenthood, and the Knesset, Israel’s parliament, has enacted legislation that establishes a regulatory system of bureaucratic approvals for various third-party medically assisted reproduction practices, based on statutory criteria of eligibility [23]. Israel’s Surrogate Mother Agreements Law (1996), was the first in the world to allow commercial surrogacy under the supervision of a statutory committee [24].

In some states in the USA, surrogacy has been legalized and regulated (California, Illinois, Arkansas, Maryland, and New Hampshire), in others it is not explicitly banned, while in still others it is strictly prohibited [25]. The practice of surrogacy has been legalized without limitations in India, Russia, Georgia, Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan, as well as in some third-world countries [26].

In the EU, surrogate motherhood is conditionally allowed in the Netherlands, Belgium and Great Britain, as the last resort for childless couples, due to the lack of institutions offering children for adoption [27]. There is a completely restrictive ban on surrogate motherhood in Austria, Norway, Sweden, France, Hungary, Italy, Switzerland, Germany and Bulgaria. In Romania, the draft bill on surrogacy was rejected at the first meeting of the commission. Surrogacy is also illegal in Croatia and Serbia.

The lack of legal regulation in the countries facilitates the growth and spread of transnational surrogacy. It is defined as the process of gestational surrogacy in which the surrogate lives in a different country to the intended parents, and hence, the commissioning parents have to travel to her country to undertake the surrogacy process [28-30].

Surrogacy as a procedure is not referred to at all in the Health Act in effect in Bulgaria [31]. Ordinance no: 28 of 20.06.2007 on activities and procedures involved in assisted reproduction, issued by the Ministry of Health, defines surrogacy as: ‘a method in which a woman carries the pregnancy for another woman, and after the birth of the child, she grants the parental rights to the biological parents’. In the ‘Assisted Reproduction’ Medical Standard to the said Ordinance, it is stated that: ‘When performing assisted reproduction, surrogate pregnancies are not allowed’ [32].

In 2010, at the initiative of patients’ organizations, the issue of surrogate motherhood was reviewed. It was put forward for discussion at a round table in Parliament, and it became clear that measures for making amendments to the Health Act, the Family Code, the Criminal Code, the Civil Code of Procedures and some ordinances, would be planned.

Five bills on surrogacy have been submitted to Parliament in the Republic of Bulgaria so far.

The amendments adopted by the 41st National Assembly at first reading, aimed at legalizing surrogacy in Bulgaria, were not put to the vote at the second reading. Meanwhile, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) adopted declaration No. 522 of 27th April 2012, signed by representatives of 11 European countries, including Bulgaria. The declaration was made following a conference in the Council of Europe on the following topic: “Surrogacy: Violation of human rights”, organized by several NGOs, with the support and participation of the European People’s Party (EPP) in PACE, includes cross-references to 16 international agreements and documents that surrogacy is in conflict with. If Bulgaria legalizes surrogate motherhood, it will be in breach of a series of international agreements and contracts to which it is a party, such as the European Convention on Human Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the Convention on Women’s Rights, etc.

In this line of thoughts, this article is aimed at surveying public opinion on surrogacy and its legalization in Bulgaria.

Materials and Methods

256 respondents, aged from 20 to 61 y (mean 36.26 ± 0.55), of whom 48.7% men and 51.3% women, took part in the anonymous survey. A special questionnaire has been developed for this survey. The questions are related to ethical, legal and social aspects of surrogacy. High school graduates were the biggest groups (81.1%).

The data was processed using the specialized statistical software SPSS 17. Descriptive statistics were presented as frequency, mean ± standard deviation. Chi square test was used to evaluate the significance of difference. A p value of <0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Public opinion in Bulgaria on surrogacy

In the survey conducted by us, to the question about the legalization of surrogacy, we also added the conditions under which the procedure could be accessible.

The findings clearly defined the grounds for the legalization of the method underlying the Bill, and showed the undoubtedly positive attitude of 90.5% of the respondents ‘for’ the legalization of surrogacy in the event of definitive inability of a woman to bear a child, and 9.5% of the surveyed stated they were ‘for’ the legalization of surrogacy in all circumstances.

As surrogacy has often been criticized for its potential exploitative nature, we asked the participants: ‘Should surrogate mothers be paid for bearing a child?’ While 41.1% of the respondents believe that the surrogate mother should be paid only the direct costs connected with the period of pregnancy, and recuperation after childbirth, 25.3% of the surveyed women and 30.2% of the surveyed men share the opinion that surrogate mothers should receive an additional remuneration. Only 15.8% think that this ‘should not be a paid service’.

In our survey we included one of the ethical questions that are the focus of intensive discussions, namely which woman should legally be considered ‘mother’ of the child. Of all respondents, 80.4% are of the opinion that the woman who has adopted and is raising the child should be considered the child’s mother. The older participants believe that the adoptive mother should legally be defined as the mother of the child, while the younger participants in the survey are hesitant and cannot decide categorically; we believe the lack of life experience accounts for this hesitation (Р<0.01, χ2=17.22) (Table 1).

| Age groups | Biological mother number (%) | Adoptive mother number (%) | Cannot decide number (%) | Total number (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| up to 25 y old | 4 (10.2) | 24 (61.5%) | 11 (28.3%) | 39 (100) |

| 26-35 | 2 (2.2) | 77 (84.6) | 12 (13.2) | 91 (100) |

| 36-45 | 2 (2.1) | 77 (81.9) | 15 (16.0) | 94 (100) |

| Over 46 | 2 (4.9) | 35 (85.4) | 4 (9.8) | 41 (100) |

| Total | 12 (4.5) | 213 (80.4) | 40 (15.1) | 265 (100) |

Table 1. Dependence of the responses concerning the definition of the term ‘mother’ on the age of the respondents.

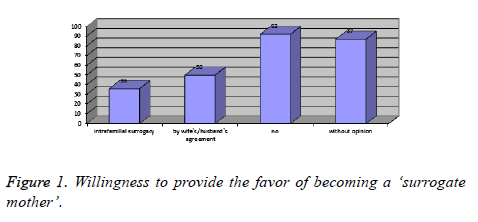

As regards the question whether they would agree to become a ‘surrogate mother’/or would give their consent to their wife to become one, 18.9% of the respondents expressed willingness to provide such type of help to a childless couple, provided their spouse agrees to that, 13.6% express their willingness to do so for their close friends/family, 34.7% were unwilling to do such a favor, and 32.8% of the respondents were undecided (Figure 1).

Most of the women are hesitant or have not thought about offering the services of a surrogate mother. Men tend to agree with this option (43.3%), in case their wives also agree (р<0.01, χ2=10.66).

Surrogacy in favor of an unrelated family

To the same question, but asked from a different point of view, namely whether the respondents themselves would resort to the services of a ‘surrogate mother’, if circumstances so require, 44.5% provided a positive answer, while a small percentage-8.3%-would do so on condition that the woman is a member of the family. Only 21.9% stated they would not consider this solution (Table 2).

| Willingness to use the services of a ‘surrogate mother’ | Absolute number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 118 | 44.5 |

| No | 58 | 21.9 |

| Cannot decide | 89 | 33.6 |

| Total | 265 | 100 |

Table 2. Willingness to use the option of surrogacy.

In the survey it is of note that the majority of the people are willing to resort to surrogacy if needed, but are unwilling to bear, or let their wife bear, another couple’s child.

Discussion

To date, in Bulgaria there is still a restrictive ban on surrogacy, but the apparent unanimity among the majority of the society, government and experts manifests an insight into the issue.

The initiative for the legalization of surrogacy in our country generated wide public interest. In 2010-2011, alongside public debate, an online survey was carried out involving 951 Bulgarian citizens [33]. To the question: ‘Should the practice of surrogacy be legalized in Bulgaria?’ 73.1% of the respondents gave a positive answer, 16.6% replied that it should not, while 10.2% said they could not decide. Both surveys evidence the highly positive attitude of our society to the issue.

Our findings completely correspond to the final position of the members of the working group on the Bill [34].

A survey with female students at the Medical University of Varna yielded similar findings: 83.3% of the respondents were in favor of surrogacy in the event of women with reproductive problems [35]. In their online survey with medical students from UK universities Bruce-Hickman et al. established that a total of 72.2% agreed with surrogacy as a means of assisted reproduction [36]. Surrogate mothering found lower overall rates of approval (43.7%), 28.5% supported an admission for medical reasons in Germany [37].

A similar survey among infertile women in Iran established a positive viewpoint regarding surrogacy. However, to increase the acceptability of surrogacy among infertile women, further efforts are needed [38].

In a survey among the Turkish population, carried out in 2009, Kilic et al. report that 24% of the participants manifested a positive attitude towards surrogate motherhood. The author’s considered that surrogate motherhood and oocyte donation will have the potential to empower women and increase their status in society in the near future. The fact that most of the infertile females stated adopting a child as the first choice indicates that this option is still considered a privilege in Turkish society [39]. Reproduction is a complex issue which has cultural, religious, ethical and legal aspects and may differ from society to society. The findings of a national survey in Japan show that approximately half of respondents approved of gestational surrogacy [40]. The findings of the authors suggested that socioeconomic status affects people's expression of their opinion regarding this issue, while attitudes toward this procedure were influenced by individual belief. The results of Constantinidis et al.’s. study exceeded the expectations, with over three-quarters of the sample indicating general support for surrogacy in Australia [41]. A relatively more favourable attitude to surrogacy is reported in surveys among the general public in Germany and Greece [42-44]. Mac Callum et al. reported that couples had considered surrogacy only after a long period of infertility or when it was the only option available [45].

If surrogacy takes place in a society that accepts this as a necessary practice for some, it is possible that actual surrogates may be better supported and less stigmatized [46].

Surrogacy has often been criticized for its potential exploitative nature, sometimes referred to as being a ‘womb for rent’ [47]. Most of our participants believe that the surrogate mother should be paid only the direct costs connected with the period of pregnancy, and recuperation after childbirth.

Brazier et al. recommend that payments to surrogate mothers should cover only genuine expenses associated with the pregnancy. Any additional payments should be prohibited in order to prevent surrogacy arrangements being entered into for financial reasons. Details of expenses should be established before any attempt is made to create a surrogacy pregnancy, and a mechanism should be put in place to ensure that documentary evidence of expenses incurred in association with the surrogacy arrangement is produced by the surrogate mother. As allowable expenses should be maternity clothing, counseling fees, healthy food, legal fees etc. [48].

Surrogacy could be argued as a treatment for some forms of childlessness. Legal restriction to ban surrogacy agreements could be argued as being paternalistic, and could force surrogacy underground [49]. Lack of clarity in legislation regarding what counts as reasonable expenses has raised concerns over covert surrogacy arrangements, which could drive vulnerable women and childless couples further away from potential protection. This could be avoided by respecting a woman’s right to participate in surrogacy, with adequate accompanying regulations [50].

Our results are in support of the need for the proposed amendment in the new Bill amending and supplementing the Family Code to be adopted; the definition proposed in the said Bill is “replacement mothering/surrogacy arrangements” (new Art.73а), defined as: ‘motherhood in which spouses (resorting to surrogacy arrangements) assign, pursuant to a contract for surrogacy arrangements, and a woman agrees to carry the pregnancy and bear a child conceived through assisted reproduction using genetic material of the spouses or the intended father’s sperm and a donor egg’ (Para. 1 of Art.73 ‘a’) [51]. This definition is aimed at amending the definition of motherhood. According to the now effective laws, the mother is the woman who gives birth to a child, including in cases of assisted reproduction. The origin of her child, even if conceived using a donor egg, is legally protected. Childbirth is an act that establishes the relationship between the woman and the child that the law defines as motherhood (Art.60, para.2 of the Family Code).

In the Republic of Bulgaria, the presumption of motherhood is widely accepted. It is stated in Art.60, Para. 2 of the currently effective Family Code that the mother of a child is the woman who has given birth to the child, including in cases when the child was conceived by means of assisted reproduction. This is one of the terms that are subject to amendment in the new Family Code.

Part of all respondents agrees with offering the service of a surrogate mother, in case their family relatives need.

The Bulgarian Bill stipulates that the surrogate mother should be a sister, cousin or mother of the intended mother, on the premises that the family ties would facilitate the settlement of potential disputes between the surrogate mother and the biological one during the pregnancy and after the child is born, as well as that the close family relations would be favorable for the pregnancy [52].

Accepting to bear a child for her sister may eliminate most of the issues discussed. A sister who makes a sacrifice for her sister who cannot have a baby eliminate the other issues related to personal benefits. The other approaches except altruism may become controversial to deliver a baby for another person. Delivering a baby for her sister may resolve the issue as to who is the real mother, genetic or gestational? Some authors established in their studies that being a surrogate motherhood for her sister is apparently more acceptable [39,53].

Cases of interfamilial surrogacy do occur as originally seen in a sister-for-sister gestational surrogacy using donor sperm reported in 1988 [54]. Soon thereafter, the case of a South African woman carrying triplets for her daughter and son-inlaw was highly publicized [55], as was the case of an American woman providing gestational surrogacy for a daughter who could not carry a pregnancy [56].

The Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine concludes that the use of gamete donors and surrogates who are family members is in many cases ethically acceptable, but that some cases raise serious problems and should not occur. To distinguish these cases, providers of ART should pay special attention to aforementioned issues of consanguinity, risks of undue influence on decisions to participate, and the chance that the arrangement in question will cause uncertainty about lineage and parenting relations [57].

The Bill amending and supplementing the Family Code (Art. 73, para.1 of FC) submitted to the 41st National Assembly provides for and regulates only cases of surrogacy in which genetic material of the intended parents is used or the embryo is created using the ovum and sperm of the intended father [34]. The aim is to preserve certain consanguinity between the child and the intended family in which the child is to be raised. It is this consanguinity between the child and one of or both intended parents that provide grounds for the intended parents to be legally recognized as the child’s parents [52].

Both in our survey and in some of the online comments on the topic, it is of note that the majority of the people are willing to resort to surrogacy if needed, but are unwilling to bear, or let their wife bear, another couple’s child [33].

The strength of the present study is the use of a nonrepresentative, self-selected sample, who didn`t report to reproductive problems. However, our results demonstrate high support levels for surrogacy. The limitation is that the discussed aspects refer only to the projected legal regulation on surrogacy arrangements in Bulgaria, since to date the adopted at first reading Bill has not been adopted by the National Assembly. Without a clearly set out legal framework concerning surrogate motherhood, the problem will continue to grow. The discussion regarding the legal regulation of surrogacy is yet to come. There are still a series of uncertainties surrounding this issue, as well as disputed points and the danger of inadequate regulation. A large group of medical specialists, psychologists, lawyers from Parliament, consultants, patients and NGOs worked for a year and a half on the Bill on surrogacy from the beginning of 2010, against the background of constant information campaigns in the media.

After receiving wide public support and achieving interparty consensus, the legalization of surrogacy has one more obstacle to overcome-the procedural requirements prior to the second reading, which to date has been postponed for an indefinite period of time.

Conclusions

The survey into the public opinion regarding the legalization of surrogacy in Bulgaria shows a positive attitude of society against the effective restrictive legal ban. The results of our survey definitively confirmed the results of the public discussions carried out in the course of the debate on the problem. This information is immediately applicable for legalization of surrogacy in Bulgaria. These important issues will be the subject of future studies.

An in-depth analysis of the topic of current issues connected with surrogate motherhood from various points of view shows that in addition to purely procedural and legal aspects, there are also numerous moral and ethical aspects that have to be discussed and complied with prior to the legalization of the procedure. The review of the relevant sources of reference showed considerable differences between the legal norms on an international and European scale. The setting out of a legal framework is also connected with the local way of life, culture and public attitudes.

In Bulgaria, infertility treatment has been part of the government policy in recent years. This policy requires not only financial resources but also an adequate legal basis, legal framework. The currently effective restrictive ban does not prevent the practice of surrogacy outside the law. In our opinion, additional measures should be provided to control the risks related to the surrogacy black market. It is also important to conduct scientific studies in different geographic regions and socioeconomic groups, which will be beneficial for evaluation and interpretation of the different society’s attitude towards the surrogacy issues.

References

- WHO. Recent advances in medically assisted conception. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. World Health Organization Technical Report Series 1992; 820.

- Bioethics A hoc C of E on. Human artificial procreation. Strasbourg, Council of Europe 1989.

- Solursh DS, Schorer JW, Solursh LP. Baby oh baby-advances in assisted reproductive technology. Med Law 1997; 16: 779-788.

- Hohman MM, Hagan C. Satisfaction with surrogate mothering: a relational model. J Hum Behav Soc Environ 2001; 4: 61-84.

- Kleinpeter CH, Hohman MM. Surrogate motherhood: personality traits and satisfaction with service providers. Psychol Rep 2000.

- van Den Akker OBA. The function and responsibilities of organisatons dealing with surrogate motherhood. Hum Fertil 1998; I: 10-13.

- Norton W, Crawshaw M, Hudson N, Culley L. A survey of UK fertility clinics approach to surrogacy arrangements. Reprod Biomed Online 2015; 31: 327-338.

- English V, Romano-Critchley G, Sheather J. Medical ethics today: the BMAs Handbook of Ethics and Law. London: BMJ Publishing Group 2004.

- Chang CL. Surrogate motherhood. Taiwan Yi Xue Ren Wen Xue Kan 2004; 5: 48-62.

- Bhatia K, Martindale EA, Rustamov O, Nysenbaum AM. Surrogate pregnancy: An essential guide for clinicians. Obstet Gynaecol 2009; 11: 49-54.

- Brinsden PR. Gestational surrogacy. Hum Reprod Update 2003; 9: 483-491.

- Utian WH, Sheean L, Goldfarb JM, Kiwi R. Successful pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer from an infertile woman to a surrogate. N Engl J Med 1985; 313: 1351-1352.

- Nakash A, Herdiman J. Surrogacy. J Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 27: 246-251.

- Mayeda M. Present state of reproductive medicine in Japan-ethical issues with a focus on those seen in court cases. BMC Med Ethics 2006; 5: 3.

- Sharma BR. Forensic considerations of surrogacy-an overview. J Clin Forensic Med 2006; 13: 80-85.

- Sifris R, Ludlow K, Sifris A. Commercial surrogacy: what role for law in Australia? J Law Med 2015; 23: 275-296.

- WMA. Statement on assisted reproductive technologies, Adopted by the 57th WMA General Assembly, Pilanesberg, South Africa, October 2006. Handbook of WMA Policies, S-2006-01-2006 Vancouver: The World Medical Association, Inc. 2010.

- British Medical Association (BMA). Changing conceptions of motherhood: the practice of surrogacy in Britain. London BMA 1996.

- Edelmann RJ. Surrogacy: the psychological issues. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2004; 22: 123-136.

- Dar S, Lazer T, Swanson S, Silverman J, Wasser C, Moskovtsev SI. Assisted reproduction involving gestational surrogacy? an analysis of the medical, psychosocial and legal issues: experience from a large surrogacy program. Hum Reprod 2015; 30: 345-352.

- Benshushan A, Schenker JG. Legitimizing surrogacy in Israel. Hum Reprod 1997; 12: 1832-1834.

- Shalev C, Gooldin S. The uses and misuses of in vitro fertilization in Israel: some sociological and ethical considerations. J Jewish Womens Studies Gender Issues 2006; 12: 151-176.

- Shalev C, Moreno A, Eyal H, Leibel M, Schuz R, Eldar-Geva T. Ethics and regulation of inter-country medically assisted reproduction: a call for action. Isr J Health Policy Res 2016; 5: 59.

- Shalev C. Halakha and patriarchal motherhood-an anatomy of the New Israeli surrogacy law. Israel Law Rev 1998; 32: 51-80.

- Lawrence DE. Surrogacy in California: genetic and gestational rights. Golden Gate Univ Law Rev 1991; 21.

- Svitnev K. Legal regulation of assisted reproduction treatment in Russia. Reprod Biomed Online 2010; 20: 892-894.

- Brahams D. The hasty British ban on commercial surrogacy. Hastings Cent Rep 1987; 17: 16-19.

- Kirby J. Transnational gestational surrogacy: does it have to be exploitative? Am J Bioeth 2014; 14: 24-32.

- Knoche JW. Health concerns and ethical considerations regarding international surrogacy. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2014; 126: 183-186.

- Lozanski K. Transnational surrogacy: Canadas contradictions. Soc Sci Med 2015; 124: 383-390.

- Law on Health, Chapter IV: Health Protection of Certain Groups of the Population, Section III: Assisted Reproduction. SG no.70/10.08.2004, in force 01.01.2005 Bulgaria 2004.

- Ordinance No 28 of 20 June 2007 on Assisted Reproduction Activities in Bulgaria; 2007.

- Krastev R, Mitev V. Correspondence between legislation and public opinion in bulgaria about accessto assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Slov J Public Heal 2013; 52: 285-291.

- Plenary stenograms 2012. Available from: http: //www.parliament.bg/bg/plenaryst/ns/7/ID/2660

- Kozovski I, Kovachev M, Angelova K, Alexandrov K, Kozovski G, Markova V. Oocyte and embryo donation and surrogacy. Religious, medico-social, ethical, financial and legal problems. Akush Ginekol Sofia 2010; 49: 43-46.

- Bruce-Hickman K, Kirkland L, Ba-Obeid T. The attitudes and knowledge of medical students towards surrogacy. J Obstet Gynaecol 2009; 29: 229-232.

- Stobel Richter Y, Goldschmidt S, Brahler E, Weidner K, Beutel M. Egg donation, surrogate mothering, and cloning: attitudes of men and women in Germany based on a representative survey. Fertil Steril 2009; 92: 124-130.

- Rahmani A, Sattarzadeh N, Gholizadeh L, Sheikhalipour Z, Allahbakhshian A. Hassankhani H. Gestational surrogacy: viewpoint of Iranian infertile women. J Hum Reprod Sci 2011; 4: 138-142.

- Kilic S, Ucar M, Yaren H, Gulec M, Atac A, Demirel F. Determination of the attitudes of Turkish infertile women towards surrogacy and oocyte donation. Pakistan J Med Sci 2009; 25: 36-40.

- Suzuki K, Hoshi K, Minai J, Yanaihara T, Takeda Y, Yamagata Z. Analysis of national representative opinion surveys concerning gestational surrogacy in Japan. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2006; 126: 39-47.

- Constantinidis D, Cook R. Australian perspectives on surrogacy? the influence of cognitions, psychological and demographic characteristics. Hum Reprod 2012; 27: 1080-1087.

- Chliaoutakis JE, Koukouli S, Papadakaki M. Using attitudinal indicators to explain the publics intention to have recourse to gamete donation and surrogacy. Hum Reprod 2002; 17: 2995-3002.

- Schroder AK, Diedrich K, Ludwig M. Attitudes toward oocyte donation and surrogate motherhood are strongly influenced by own experiences. Zentralbl Gynakol 2004; 126: 24-31.

- Poote AE, van den Akker OB. British womens attitudes to surrogacy. Hum Reprod 2009; 24: 139-145.

- MacCallum F, Lycett E, Murray C, Jadva V, Golombok S. Surrogacy: the experience of commissioning couples. Hum Reprod 2003; 18: 1334-1342.

- Sharma BR. Forensic considerations of surrogacy-an overview. J Clin Forensic Med 2006; 13: 80-85.

- Wilkinson S. The exploitation argument against commercial surrogacy. Bioethics 2003; 17: 169-187.

- Brazier M, Golombok S, Campbell A. Surrogacy: review for the UK Health Ministers of current arrangements for payments and regulation. Hum Reprod Update 1997; 3: 623-628.

- Brazier M, Cave E. Medicine, patients and the law (5th Edn.). London: Penguin 2011: 64-65.

- Burrell C, O’ Connor H. Surrogate pregnancy? ethical and medico-legal issues in modern obstetrics. Obstetr Gynaecol 2013; 15: 113-119.

- Stavru S. Potential conflicts with criminal law significance between the replacement mother and the spouses in the substitute motherhood. Thesis 2011; 1: 95-105.

- Law amending and supplementing the Family Code. Available from: http://parliament.bg/bills/41/154-01-84.pdf. (in Bulgarian)

- Kirkman M, Kirkman A. Sister-to-sister gestational surrogacy 13 years on: A narrative of parenthood. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2002; 20: 135-147.

- Leeton J, King C, Harman J. Sister-sister in vitro fertilization surrogate pregnancy with donor sperm: The case for surrogate gestational pregnancy. J Vitr Fertil Embryo Transf 1988; 5: 245-248.

- Michelow MC, Bernstein J, Jacobson MJ, McLoughlin JL, Rubenstein D, Hacking AI. Mother-daughter in vitro fertilization triplet surrogate pregnancy. J Vitr Fertil Embryo Transf 1988; 5: 31-34.

- Woman is pregnant with grandchildren. An act of love for barren doughter. Chicago Tribune 1991.

- ASRM TEC. Using family members as gamete donors or surrogates. Fertil Steril 2012; 98: 797-803.