Research Article - Asian Journal of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences (2016) Volume 6, Issue 59

Study of Intestinal Parasitosis among School Children of Kathmandu Valley, Nepal

Khushbu Yadav1* and Satyam Prakash2

1Medical Microbiologist & Lecturer, Krishna Medical Technical Research Center, Purwanchal University, Janakpurdham, Nepal

2Department of Biochemistry, Janaki Medical College Teaching Hospital, Tribhuvan University, Janakpurdham, Nepal

Accepted date: December 08, 2016

Abstract

Background and Objectives: Intestinal parasitic infection such as amoebiasis, ascariasis, ancylostomiasis and trichuriasis are one of the major health problems in children developing countries like Nepal. Around 450 million children are ill due to these infections. Therefore, this study was focused to find out the present situation of the parasitic infections among school children of Kathmandu Valley. Methods: A total of 507 stool samples from healthy students were collected in dry, clean and screw capped plastic container and were preserved with 10% formalin. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data on predisposing factors. The stool samples were examined by direct microscopy and confirmed by concentration methods. Modified Ziehl Neelsen (ZN) staining was performed for the detection of coccidian parasites. Results: The incidence of intestinal parasitic infection was 58.77% (Boys=61.85% vs. Girls=53.84%). The highest number of parasitic infection occurred between 6 to 10 years aged (62.84%) and was statistically significant (p=0.001). Entamoeba histolytica was found to be predominant parasites to cause parasitic infection. The type of infection in relation to gender was to be statistically significant (p=0.001). The parasitic infection was found more in dalit children and in symptomatic children. The parasitic infection rate was found higher in not using anti-parasitic drug (72.28%) than the drug users (37.08%). Conclusion: Lack of awareness, improper hand washing after defecation, not taking anti- parasitic drug and unsafe drinking water was some of the predisposing factors. Improvements in personal hygiene and sanitation, water supplies, health education and socio-economic status will help to prevent from intestinal parasitic infection.

Keywords

Intestinal parasitic infection, Amoebiasis, Entamoeba histolytica, Diarrhoea, Soil-transmitted helminth, Schoolchildren.

Introduction

Nepal is a small underdeveloped nation located in South Asia and has full of ancient glories rich in tradition, culture and civilization which exhibits social, ethnical, linguistic and cultural diversity with various infectious diseases including intestinal parasitosis. It is alone one of the most common public health problems in all over Nepal [1]. The distribution and prevalence of the various intestinal parasites species depend on social, geographical, economical and inhabitant customs [2].

Intestinal parasitosis (i.e. Giardiasis, amoebiasis, ascariasis, ancylostomiasis, fascioliasis and taeniasis) are being highly prevalent caused by protozoa and helminths which are spreading faeco-orally through contaminated sources [3]. Helminthic infections are associated with poor growth, reduced physical activity, impaired cognitive function, learning ability, nutritional deficiencies, particularly of iron and vitamin A, with improvements in iron status and increments in vitamin-A absorption seen after deworming [4].

Most common intestinal parasites reported from school going children in Nepal are Ascaris lumbricoides, Hymenolepis nana, Hookworm, Trichuris trichiura, Giardia lamblia and Entamoeba histolytica. Of the protozoal infections, amoebiasis and giardiasis are most frequently reported. Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura and Hookworms, collectively referred to as soil-transmitted helminths (STHs) which are the most common intestinal parasites [5]. These parasites are associated with diverse clinical manifestations such as malnutrition, iron deficiency anemia, malabsorption syndrome, intestinal obstruction, mental and physical growth retardation [6].

Although, these organisms may infect people of all ages but children are often infected occurring with high intensity in 3-12 year age group [7,8] due to use of drinking water and poor personal hygiene [9] which are major causes of morbidity and mortality among school aged children. As a result, they experience growth stunting and diminished physical fitness as well as impaired memory and cognition [10-13]. The World Health Organization estimates that over 270 million pre-school children and over 600 million of school children where the parasites are intensively transmitted [14]. At least 750 million episodes of diarrhoea occur per year in developing countries that results in five million deaths [15].

Intestinal parasitic infection is a serious public health problem throughout the world particularly in many developing countries [16]. About 70% of health problems are due to infectious diseases and diarrheal disease alone is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in Nepal [17,18]. Nearly 200 million people were infected with Giardia lamblia while Entamoeba histolytica infects 10% of the world population [19]. More than one billion of the world’s population including at least 400 million school children is chronically infected with Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura and Ancyclostoma doudenale [20,21].

Hospital based studies have shown a declining trend during a period of ten years [22]. Poverty, lack of awareness, failure to practice proper hand washing after defecation, unsafe drinking water and use of improper toilets are some of the reasons that are not totally eradicated from most of the parts in Nepal [6,23]. Because of these reasons most of the school going children is still suffering from parasitic infections. Socio-economic and cultural factors and lack of adequate basic sanitation have caused the children more vulnerable to intestinal parasitic infections here [23]. Parasitosis has been one of the major causes for the visit to health care facilities in Nepal [24].

Therefore, this study was designed to determine the incidence of intestinal parasitic infection in Dallu area of Kathmandu valley which reflects the sanitary condition, socio-economic impact, environmental impact, consciousness about the factors causing the disease and health education among the school children. The findings of this study might be helpful in strengthening the information available so far and encourage policy makers to design effective strategies to prevent intestinal parasitic infections.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional descriptive study was done among the school going children in Dallu area, Kathmandu valley, Nepal in 2014 AD. This study comprised of 521 schoolchildren and was conducted at Department of Microbiology, National College, Khushibu, Nayabazar, Kathmandu.

Ethical consideration

Informed verbal consent was obtained from the participants prior to the study before proceeding the questionnaire and specimen collection. Work approval was taken from Department of Microbiology, National College, Khushibu, Nayabazar, Kathmandu and from the school in Dallu area of Kathmandu valley.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Those participants who came with stool sample were included and those without stool sample were excluded from the study.

Sample collection and transportation

Students in a class were given a brief description about the importance of examination of stool and the impact of intestinal parasite upon health. The plastic containers were labeled with children’s name and roll number, date and time of collection and distributed to the students. During the distribution of containers, questionnaire accompanying the queries about name, age, demographic data, sex, family size, clinical history such as gastrointestinal tract associated symptoms, secondary infections and the use of any medicine (ARV or others) and hygienic practices were filled by interviewing them or with the help of their care takers and teachers. They were advised to pass the stool on a sterile paper (to avoid contamination from toilet pan) and collect in the container with the spatula both provided to them. Single specimen was collected from each individual. They were advised not to contaminate the stool with water and urine and asked to bring about half the container of stool samples and were immediately transported to the Microbiological laboratory of National College. The collected samples were fixed using 10% formalin solution.

Sample processing

The collected samples were examined by macroscopic and microscopic examination.

Macroscopic examination

The color, consistency, presence of blood and mucus, presence of adult worms and segments and any other abnormalities were observed. Based on the color, the stool specimen were categorized into two groups i.e. Normal color of stool (yellowish brown) and abnormal color of stool (muddy, black, pale etc). Based on consistency, stool specimens were categorized as formed, semi-formed and loose. The stool specimens were observed whether it contains blood and mucus or not, adult worms and segments or not.

Microscopic examination

Microscopic examination was done for the detection and identification of protozoal cysts, oocysts, trophozoites and helminthic eggs or larva by wet preparation (normal saline and iodine preparation), concentration and modified Ziehl Neelsen (ZN) methods. Samples were concentrated by centrifugation before performing wet mount. Direct wet mounts of stool specimens were prepared in a drop of normal saline for the observation of pus cells, ova, cyst and trophozoites of parasites. Iodine preparations of stools were prepared in 5 times diluted Lugol’s iodine. Concentration methods (formal-ether sedimentation technique or floatation technique by using Sheather’s sugar solution) and modified ZN staining technique were employed for all the stool specimens [25]. The slides were observed first under low power (10x) and followed by high power (40x) of the microscope.

Statistical analysis

The obtained data was performed using SPSS 20 version and Microsoft Excel 2007. Association of intestinal parasitosis with demography, personal habits and symptoms were assessed by using the Chi-square test and p<0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Age and gender wise distribution of children

Among total respondents, 312 (61.53%) were boys and 195 (38.46%) were girls, 163 (32.14%) were of less than 6 years, 218 (42.98%) were between 6-10 years and 126 (24.85%) were of greater than 10 years. The results are shown in Table 1.

| Age group (yrs) | Gender | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boys (%) | Girls (%) | ||

| <6 | 94 (30.12) | 69 (35.38) | 163 (32.14) |

| 6-10 | 137 (43.91) | 81 (41.53) | 218 (42.98) |

| >10 | 81 (25.96) | 45 (23.07) | 126 (24.85) |

| Total | 312 (61.53) | 195 (38.46) | 507 |

Table 1: Pattern of age and gender of study population.

Macroscopic examination of stool sample

A total of 507 stool sample were collected and examined from the children. Of total, 206 (40.63%) stool samples had normal color, 385 (75.93%) stool samples with normal consistency, 97 (19.13%), 88 (17.35%) and 5 (1%) stool samples were containing blood, mucus and worms respectively. The results are shown in Table 2.

| Properties | Macroscopic Examination | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (%) | Abnormal (%) | Presence (%) | Absence (%) | ||

| Color | 301 (59.36) | 206 (40.63) | - | - | 507 |

| Consistency | 122 (24.06) | 385 (75.93) | - | - | |

| Blood | - | - | 97 (19.13) | 410 (80.86) | |

| Mucus | - | - | 88 (17.35) | 419 (82.64) | |

| Worms | - | - | 5 (1) | 502 (99.01) | |

Table 2: Physical properties of Stool sample.

Incidence of parasitic infection in relation to gender difference

Of total respondents, 298 (58.77%) respondents had parasitic infection. The highest number of parasitic infection were seen in boys 193 (61.85%) than girls 105 (53.84%) which was found to be statistically insignificant (p=0.327). The results are shown in Table 3.

| Gender | Total (%) | Positive cases (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | 312 | 193 (61.85) | 0.327 |

| Girls | 195 | 105 (53.84) | |

| Total | 507 | 298 (58.77) |

Table 3: Frequency of parasitic infection in relation to gender.

Incidence of parasitic infection in different age group

Of total positive cases, the highest number of parasitic infection was seen between 6 to 10 years age group 137 (62.84%) followed by below 6 years age group with 98 (60.12%) and was found statistically significant (p=0.001). The results are shown in Table 4.

| Age group (yrs) | Total | Positive cases (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| <6 | 163 | 98 (60.12) | 0.001 |

| 6-10 | 218 | 137 (62.84) | |

| >10 | 126 | 63 (50) | |

| Total | 507 | 298 |

Table 4: Frequency of positive cases in relation to age group.

Detection of pattern of parasites

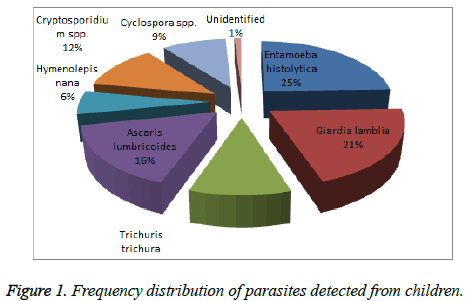

A total of 295 parasites were identified and 3 (1%) were unidentified. Of 295, 73 (25%) were Entamoeba histolytica, 61 (21%) were Giardia lamblia, 31 (10%) were Trichuris trichura, 49 (16%) were Ascaris lumbricoides, 18 (6%) were Hymenolepis nana, 35 (12%) were Cryptosporidium spp. and 28 (9%) were Cyclospora spp. Among all parasites detected, Entamoeba histolytica was predominant parasites to cause diarrhoea, which is the main symptoms of parasitic infection. The results are shown in Figure 1.

Distribution of parasite detected according to type of infection

Of total positive cases, single parasite infestation 215 (72.14%) was found to be more than mixed parasites infestation 83 (27.85%). The type of infection in relation to gender was seen to be statistically significant (p=0.001). The results are shown in Table 5.

| Types of infection | Gender | Total positive cases (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys (%) | Girls (%) | |||

| Single infection | 119 (61.65) | 96 (91.42) | 215 (72.14) | 0.001 |

| Mixed infection | 74 (38.34) | 9 (8.57) | 83 (27.85) | |

| Total | 193 | 105 | 298 | |

Table 5: Type of infection in relation to gender.

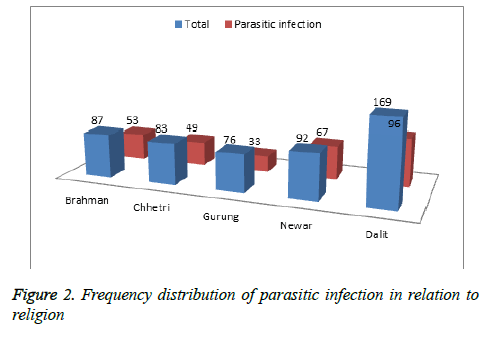

Religion wise distribution of parasitic infection

Among total respondents, the highest numbers of children were Dalit. The parasitic infection was found to be more in Dalit children (96) followed by Newar (67) and Brahman children (53). The results are shown in Figure 2.

Symptom wise distribution of positive cases

The occurrence of parasitic infection in symptomatic children was found to be 107 (98.16%) and in asymptomatic children 191 (47.98%) and was statistically significant (p=0.001). The results are shown in Table 6.

| Parameters | Total | Positive cases (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptomatic | 109 | 107 (98.16) | 0.001 |

| Asymptomatic | 398 | 191 (47.98) | |

| Total | 507 | 298 (58.77) |

Table 6: Relation of parasitic infection in relation to symptoms.

Incidence of parasitic infection in relation to antiparasitic drug

The parasitic infection rate was found to be higher in not using anti-parasitic drug 193 (72.28%) than drug users 89 (37.08%). The results was found to be statistically significant (p=0.001) and are shown in Table 7.

| Anti-parasitic drug taken | Total | Positive cases (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 240 | 89 (37.08) | 0.001 |

| No | 267 | 193 (72.28) | |

| Total | 507 | 298 |

Table 7: Relation of parasitic infection in relation to symptoms.

Possible risk factors associated with medical history of parasites

The highest percentage of positive cases of parasitic infection was found in those children who used direct tap water 120 (91.60%), who did not trimmed nail 201 (62.81%) and who washed hands with mud 215 (97.28%). The result was found to be statistically significant and is shown in Table 8.

| Type of drinking water | Total | Positive cases (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boiled tap water | 376 | 178 (47.34) | 0.0001 |

| Direct tap water | 131 | 120 (91.60) | |

| Total | 507 | 298 | |

| Nail trimming | |||

| Done | 187 | 97 (51.87) | 0.001 |

| Not done | 320 | 201 (62.81) | |

| Total | 507 | 298 | |

| Hand washing habit | |||

| With soap | 286 | 83 (29.02) | 0.0001 |

| With mud | 221 | 215 (97.28) | |

| Total | 507 | 298 | |

Table 8: Relation of Possible risk factors with medical history of parasites.

Discussion

The differences in geographical setting, socioeconomic conditions, cultural practices, awareness programmes and the supply of drinking water can bring vast differences in the prevalence of parasitic infections in different parts of the world [22]. Intestinal parasitic infection is an important public health problem in Nepal because of its high morbidity and mortality [26]. Nepal is a small impoverished country where intestinal parasitosis being highly prevalent and varies considerably from one study to another [3].

This study reflects 507 school children were examined for parasitic infection where 312 (61.53%) were boys and 195 (38.46%) were girls, 163 (32.14%) were of less than 6 years age, 218 (42.98%) were between 6-10 years and 126 (24.85%) were of greater than 10 years age. The present study revealed a total of 507 stool samples were collected and examined macroscopically. Of total stool samples, 40.63% stool samples had normal color, 75.93% had normal consistency. Similarly, 19.13%, 17.35% and 1% stool samples were containing blood, mucus and worms respectively. A similar type of study done by Tiwari et al., 2013 amongst the school going children from different villages of Dadeldhura district reported, out of total 530 stool samples, 88.30% and 81.10% were normal in color and consistency respectively. Mucus was present 8.10% samples but none of the sample was seen containing blood [27] which is not in accordance with this study. This may be due to use of contaminated drinking water, inadequate sanitary conditions and poor personal hygiene.

This study represents that the incidence of parasitic infection was 58.77%. Most of the boys (61.85%) were infected with parasites than girls (53.84%) which was found to be statistically insignificant (p=0.327). A study conducted by Shrestha et al., reported the incidence of parasitic infection was 21.05% and boys (22.78%) were more infected than girls (19.38%) and was considered statistically insignificant (p>0.05) [23]. Similarly, a study done by Bhattachan et al., reported the incidence of parasitic infection in school children at Saktikhor, Jutpani-3 in Chitwan district of Nepal was 23.3%. The infection rate of intestinal parasites in girls (24.8%) were higher than boys (21.8%) and were considered as statistically insignificant (p=0.39) [28]. Pradhan et al., conducted a same study at a rural public school located in the northeast part of the Kathmandu Valley reported the prevalence rate was 23.7% and boys children (28.2%) were more infected with parasitic infection than girls children (20.2%) and was not significant statistically (P>0.05) [29]. Tiwari et al., reported the prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection was 31.13%. Male were highly infected than female and considered as statistically insignificant (p>0.05) [27]. Similar types of finding were also obtained in study conducted by Khanal et al., [30]. The above all are not in accordance with this study. This may be due to poor water supply system, highly polluted environment and over-crowded population of Kathmandu Valley.

In this study, the highest number of parasitic infection was seen between 6 to 10 years age of 62.84% followed by below 6 years age group with 60.12% and was found to be statistically significant (p=0.001). Bhattachan et al., reported parasitic infection rate between aged 0-5 years were highest 26.9% followed by 6-12 years 25.3% and 13- 18 years 15.2% , (p=0.35) [28]. Pradhan et al., reported intestinal parasitic infection was highest among children aged less than 6 years (37.5%) followed by children aged 6-10 years (31.6%) and children aged more than 10 years (16.8%) [29]. Similarly, Tiwari et al., found the highest prevalence of parasitic infection was found in the children of age group 4-6 years (38.18%) and result was not significant statistically (P>0.05) [27]. A similar type of study conducted by Khadka et al., revealed the occurrence of parasitic infection was highest in age group 8-12 years and lowest in age group 12-15 years; however, it was statistically insignificant [30]. Study conducted by Shrestha et al., reported that there was higher prevalence in children belonging to age between 10-14 years (23.33%) (p<0.05) [23]. Khanal et al., found children aged 6-8 years were found to be highly infected (21.4%) followed by 9-12 years (18.6%) [30]. The above all seems that the highest incidence of parasitic infection occurred in the age group of 1-10 years which are almost in accordance with this study. This may be due to the carelessness of the children towards their personal hygiene and engagement of this age group in different types of games in polluted environment.

The present study established that altogether 7 different parasites infect the children of Kathmandu valley. This study found the most prevalent parasites that cause infection in children were 25% Entamoeba histolytica, 21% Giardia lamblia, 10% Trichuris trichura, 16% Ascaris lumbricoides, 6% Hymenolepis nana, 12% Cryptosporidium spp. and 9% Cyclospora spp. Entamoeba histolytica was predominant parasites to cause parasitic infection. Shrestha et al., also found Entamoeba histolytica was found to be predominant (9.23%) followed by Giardia lamblia (5.76%). Trichuris trichuria (5%) was the commonest helminth accompanied by Ancylostoma duodenale (2.65%) and Ascaris lumbricoides (2.3%) [23]. Both study revealed Entamoeba histolytica was the prime cause of intestinal parasitic infection which is similar to this study.

But, a similar study conducted by Bhattachan et al., reported that infection rate of G. lamblia and E. coli are highest in common 17.0% whereas least in E. histolytica 11.0% [29]. Pradhan et al., reported Giardia lamblia was the most common (58.6%) followed by Entamoeba histolytica/dispar (19.6%). Hymenolepis nana was the most common (21.7%) and only one Hookworm, Trichuris trichiura and Ascaris lumbricoides was detected [30]. Tiwari et al. found the most prevalent species were Hymenolepis nana (46.56%), Hookworm (27.58%), Ascaris lumbricoides (17.82%), Giardia lamblia (7.47%) and Trichuris trichiura (0.57%) [28]. Khadka et al., depicts that the most common intestinal parasite was Giardia lamblia (33.3%), Entamoeba histolytica (26.6%), Ascaris lumbricoides (26.6%), Trichuris trichura and Hook worm (6.6%) of both. Khanal et al., found T. trichiura was found highly prevalent (32.0%) followed by A. lumbricoides (20.0%), H. nana (16.0%) and hookworm (8.0%) [30]. The above all are not concurred with this study.

This study found that single parasites infestation was found to be more (72.14%) than mixed parasites infestation (27.85%). The type of infection in relation to gender was seen to be statistically significant (p=0.001). Similar finding was also reported by Shrestha et al. [23].

This study highlights that the parasitic infection was found more in Dalit children (96) followed by Newar (67) and Brahman children (53). Intestinal infection was highest in Dalit students in the study conducted by Khadka et al., and Bhattachan et al., [28,30] which is similar to this study. This may be due to uneducated lower cast parents who are not aware of using well managed latrine. Dalits comprised the majority [31] which can be endorsed to their detachment to safe drinking water, unhygienic personal habits due to lack of knowledge, awareness and also indirectly to their occupation as farmers.

The present study also revealed that the occurrence of parasitic infection in symptomatic children was 98.16% and in asymptomatic children was 47.98% and found statistically significant (p=0.001). This finding was in agreement with the study done by Khadka et al., Sherchand et al., Sherchand et al.,; Adhikari et al. [30,32-34] which is in accordance with this study. This may be due to the symptoms such as private part itching, nausea, abdominal discomfort, diarrhoea, cough, dyspaenia and anemia are the prime indicator of parasitic infestation.

The parasitic infection rate was found to be higher in not taking anti-parasitic drug (72.28%) than drug user (37.08%) and was statistically significant (p=0.001). A similar finding was also obtained in the study conducted by Bhattachan et al., Rajeswari et al., Thapa et al., [28,35,36] which is in agreement with this study. This may be due to taking anti-parasitic in six month had significantly lower prevalence rate of parasitic infection. The importance of periodic administration of anti-parasitic drug used by children is effective.

This study reflects that the highest percentage of positive cases of parasitic infection was found in those children who used direct tap water, who did not trimmed nail and who washed hands with mud with 91.60%, 62.81%, 97.28% and was statistically significant (p=0.0001, p=0.001, p=0.0001) respectively. Shrestha et al., also reported the highest percentage of positive cases of parasitic infection occurred without trimming nail of 33.33% and was found to be statistically significant (p<0.05) [23]. Similar findings were also reported by Yodomani et al., Suharijha and Bintari [37,38] which is in accordance with this study. This may be due to habit of suckling of fingers, unhygienic playing fields and eating with unwashed hands are the major output risk factors in causing intestinal parasitic infection.

Conclusion

This study highlights the incidence of intestinal parasites is copious among school children of Kathmandu Valley. No significant differences in prevalence of intestinal parasites were observed between boys and girls. However, significant difference in prevalence of parasitic infection was found between age 6-10 years and below 6 years. This study has shown that no intake anti-parasitic drug, unsafe drinking water, nail hygiene and washing hand habit with mud are closely associated with the prevalence of intestinal infections. There is a need for intensive and habitual health education for behavioural changes related to personal hygiene and mass treatment for the effective control of intestinal parasitic infections. The control measures include treatment of infected individuals, improvement of sanitation practices and provision of safe drinking water.

In order to prevent this infection appropriate health education should be given to children and their parents concerning disease transmission, personal hygiene and safe drinking water as well as periodic administration of anti-parasitic drug. Schools should compulsory provide anti-parasitic drugs for their students in every 6 months along with maintenance of hygienic practices. Efforts from the municipality to improve the quality of drinking water supply and the types of toilets being used will certainly restrict the number of parasitic infections. Dalit cast parents and children should be provided awareness programme related with parasitic infection.

Limitation

The limitation of this study was that most of the students in the study were from same geographical background and there was no association between the environment factors and the intestinal parasites incidence.

Acknowledgement

We heartily acknowledge Department of Microbiology, National College, Khushibu, Kathmandu, Nepal for their cordial support during this research.

References

- Ishiyama S, Rai SK, Ono K, Uga S. Small-scale study on intestinal parasitosis in a remote hilly village in Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2003; 5:28-30.

- WHO. Winning the fight against neglected tropical diseases. 2006.

- Rai SK, Hirai K, Abe A. Intestinal parasitosis among school children in a rural hilly area of the Dhading district, Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2002; 4:54-58.

- WHO, UNICEF. Prevention and control of schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminthes. NY, USA, 2004.

- Mehraj V. Prevalence of and factors associated with intestinal parasites among children from 1 to 5 years of age in an urban slum of Karachi, (Ph.D Thesis) Age Khan University, Department of Community Health Sciences. 2006.

- Gyawali N, Amatya R, Nepal HP. Intestinal parasitosis in school going children of Dharan municipality, Nepal. Trop Gastroenterol. 2009; 30:145-147.

- Albonico M, Crompton DW, Savioli L. Control strategies for human intestinal nematode infections. AdvParasitol. 1999; 42:277-341.

- Savioli L, Bundy D, Tomkins A. Intestinal parasitic infections: a soluble public health problem. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1992; 86:353-354.

- Al-Agha R, Teodorescu I. Intestinal parasites infections and anaemia in primary schools children in G29 Gonernorates Palestine. Roum Arch Microbiol Immunol. 2000; 59:131-143.

- Stephenson LS, Latham MC, Ottesen EA. Malnutrition and parasitic helminth infections. Parasitology. 2000; 121: 23-38.

- Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M , Geiger SM, Loukas A, Diemert D. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. The Lancet. 2006; 367:1521-1532.

- Crompton DW, Nesheim MC. Nutritional impact of intestinal helminthiasis during the human life cycle. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002; 22:35-59.

- TchuemTchuenté LA. Control of soil-transmitted helminths in sub-Saharan Africa: diagnosis, drug efficacy concerns and challenges. Acta Trop 2011; 1:4-11.

- WHO. Neglected Tropical Diseases - PCT Databank. 2010.

- Shakya B, Rai SK, Singh A, Shrestha A. Intestinal parasitosis among the elderly people in Kathmandu Valley. Nepal Med Coll J. 2006; 8:243-247.

- World Health Organization. Control of Tropical Diseases WHO, Geneva; 1998.

- Agwa NA. Incidence of intestinal helminthiasis in schoolchildren in Aba urban city, Abia state, Nigeria. Environ Health and Human DevInt J. 2001; 1:47-51.

- Meremikwu MM, Antia-Obong OE, Asindi AA, Ejezie GC. Prevalence and intensity of intestinal helminthiasis in Pre-School children of peasant farmers in Calabar, Nigeria. Nigerian J Med. 1995; 2:40-44.

- Salako AA. Effects of portable water availability on intestinal parasitism among rural school children with sewage disposal facilities in the Mjidum and Owutu sub- urban community of Lagos state. Nigeria J Med Pract. 2001; 39:3-4.

- World Health Organization. Prevention and control of Intestinal parasitic infections. World Health Organization Technical report. 1998a; 749-783.

- WHO. Soil-transmitted helminth infections. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/ factsheets/fs366/en/. Accessed on 10 August, 2012.

- Chandrashekhar TS, Joshi HS, Gurung M, Subba SH, Rana MS, Shivananda PG. Prevalence and distribution of intestinal parasitic infestations among school children in Kaski District, Western Nepal. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2005; 4:78-82.

- Shrestha A, Narayan KC, Sharma R. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitosis among School Children in Baglung District of Western Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2012; 10:3-6.

- Department of Health Services. Annual Report. 2010: 201-202.

- John DT, Petri WA.Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology. 2006, St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 9.

- Rai SK, Gurung R, Saiju R, Bajracharya L, Rai N, Gurung K, Shakya B, Pant J, Shrestha A, Sharma P, Shrestha A, Rai CK. Intestinal parasitosis among subjects undergoing cataract surgery at the eye camps in rural hilly areas of Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2008; 10:100-103.

- Tiwari RB, Chaudhary R, Adhikari N, Jayaswal KS, Poudel PK, Rijal RK. Prevalence of Intestinal Parasitic Infections among School Children of Dadeldhura District, Nepal. JHAS. 2013; 3: 14-16.

- Bhattachan B, Panta YB, Tiwari S, Thapa Magar D, Sherchand JB , Rai G, Rai SK . Intestinal Parasitic Infection among School children in Chitwan district of Nepal.JInstit Med. 2015; 37:2 79-84.

- Pradhan P, Bhandary S, Shakya PR, Acharya T,Shrestha A. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections among public school children in a rural village of Kathmandu Valley Nepal Med Coll J. 2014; 16:50-53.

- Khanal LK, Choudhury DR,Rai SK, Sapkota J, Barakoti A. Prevalence of intestinal worm infestations among school children in Kathmandu, Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2011; 13:272-274.

- Khadka SK, Kaphle PH, Gurung K, Shah Y, Sigdel M. Study of Intestinal Parasitosis among School Going Children in Pokhara, Nepal . JHAS. 2013; 3:47-50.

- Adhikari NA, Rai SK, Singh A, Dahal S, Ghimire G. Intestinal parasitic infections among HIV seropositive and high risk group subjects for HIV infection in Nepal. Nepal Med Coll J. 2006; 8:166-170.

- Sherchand PS, Joshi RD, Adhikari N, Gurung K, Pant K, Pun R. Intestinal parasitosis among school going children. JHAS. 2010; 1:12-15.

- Sherchand JB, Ohara H, Sherchand S, Cross JH, Shrestha MP. Intestinal parasitic infections in rural areas of Southern Nepal. Inst Med J Nep.1997; 19:115-121.

- Rajeswari B, Sinniah B, Hussein H. Socio-economic factors associated with intestinal parasites among children living in Gombak, Malayasia. Asia Pacific J Pub Health. 1994; 7:21-25.

- Thapa Magar D, Rai SK, Lekhak B, Rai KR. Study of parasitic infection among children of SukumbasiBasti in Kathmandu valley. Nepal Med Coll J. 2011; 13:7-10.

- Yodomani B, Sornmani S, Phatihatakorn W, Harinasuta C. Re-infection of Ascariasis after Treatment with PyrantelPamoate and the Factors Relating to its active Transmission in a slum in Bangkok. In: Collected papers on the control of soil transmitted helminthiasis. Asian Parasite Control Organ. 1983; 2:89-103.

- SuharijhaI, BintariR. Nail and dust examination for helminthic eggs in orphanages. In: Collected papers on the control of soil transmitted helminthiasis. Asian Parasite Control Organ. 1983; 6: 59-61.