Research Article - Journal of Psychology and Cognition (2017) Volume 2, Issue 1

Screening for problem behaviors in Emirati preschool children.

Lolowa A Almekaini*, Hassib Narchi, Taoufik Zoubeidi, Omer Al Jabri, Abdul-Kader Souid

Departments of Pediatrics, UAE University, Al-Ain, UAE

- *Corresponding Author:

- Lolowa A Almekaini

Departments of Pediatrics

UAE University Al-Ain, UAE

Tel: +971-3-713-7335

Fax +971-3-767-2022

E-mail: lolwa.mukini@uaeu.ac.ae

Accepted date: on January 25, 2017

Citation: Almekaini LA, Narchi H, Zoubeidi T, et al. Screening for problem behaviors in Emirati preschool children. J Psychol Cognition. 2017;2(1):21-25.

DOI: 10.35841/psychology-cognition.2.1.21-25

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Psychology and CognitionAbstract

Background: Behavioral symptoms in schoolchildren have been observed in preschoolers. As severe symptoms are more likely to persist and require treatment, proper assessment and early intervention are required in that age group. Aim: In this cross-sectional, community-based study we examined problem behaviors in Emirati children between the ages of 1.5 to 5 years.

Method: The study was conducted between October 2015 and June 2016 at the Ambulatory Health Services in Abu Dhabi. Parents (84.9%) and other primary caregivers (15.1%) reported on internalizing and externalizing behavior problems using the Arabic version of Child Behavior Checklist/1.5-5 (CBCL/1.5-5) which was used to analyze the resulting behavior profiles.

Results: Girls constituted 47.7% of the 815 participants. Problems occurred more commonly in boys than in girls. Boys had significantly more internalizing problem items than girls (p=0.04). Fifty-five (6.7%) children had only abnormal (T-scores ≥ 70) internalizing problem items, one (0.1%) child had only abnormal externalizing problem items, while 13 (1.6%) children had both. The prevalence of autism spectrum on the Motor and Social Development (MSD)-oriented scale was 13.6%, anxiety 9.6% and depression 8.0%.

Conclusion: Frequent problem behaviors occur in preschool children who, therefore, require further evaluation and early intervention to prevent problems later in life.

Keywords

Preschool children, Internalizing and externalizing problems, Behavioral syndromes, Autism spectrum, CBCL/1.5-5.

Introduction

Several studies have confirmed that problem behaviors are commonly displayed in preschool children [1-4]. Screening young children for behavioral and emotional problems should, therefore, be considered a national priority [5].

Reports on mental health problems in toddlers and young children in the Arab world are scarce [6-10]. One regional study showed that behavior problems occur in 13.5% of children between the ages of 5.4 and 16.6 years [9]. In a more recent study, confirmed childhood autistic disorders were reported in 29 per 10,000 children [10]. Follow-up studies are needed to determine how the prevalence of these childhood problems changes in this rapidly developing society.

Behavior symptoms in schoolchildren, such as anxiety, depression, aggression, hyperactivity and impulsivity have been observed in preschoolers [11,12]. It has been shown that the presence of internalizing and externalizing symptoms between the ages of 2 and 3 years predicts their persistence at the age of 10 years [13] and this has been referred to as homotypic stability. In contrast, the term heterotypic stability refers to the different behavior problems that may also evolve over time [5]. Severe and complex symptoms (e.g., coexisting internalizing and externalizing problems) are more likely to persist and require early treatment to prevent the development of progressive illnesses [4]. Therefore, early proper assessment and intervention are most needed for affected young children.

Population-based studies are, therefore, needed to determine the epidemiology, risk factors and outcome of emotional and behavioral problems in preschool children in our country. We have undertaken this study to assess the prevalence of behavioral problems in Emirati children aged 1.5 to 5 years, using the Child Behavior Checklist/1.5-5 (CBCL/1.5-5) as a screening instrument.

Methods

In this cross-sectional, community-based study, we used the standardized and validated Arabic version of CBCL/1.5- 5 years, which was completed mainly by parents in the presence of a trained staff member [6-8]. Families presenting to the Ambulatory Health Services (Abu Dhabi) for a routine healthcare visit between October 2015 and June 2016 were recruited for the study.

The parent’s ratings of the child’s problem behavior were fitted into seven internalizing and externalizing symptoms and five DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual)-oriented diagnoses and analyzed on the CBCL/1.5-5 scales [1,2]. A T-score of ≤ 64% was considered normal, 65-69% borderline and ≥ 70% abnormal [6,7]. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committees for Human Research of the Medical District and the Ambulatory Health Services (Health Authority of Abu Dhabi). Written, informed consent was obtained from the parents or primary care giver of all participants and anonymity was assured.

Descriptive statistics were used for assessing prevalence. Logistic regression and chi-square test were used to test for significant (two-tailed p<0.05) associations of abnormal symptoms in different groups.

Results

The children’s characteristics are shown in Tables 1A and 1B. Their age (mean ± SD) was 38.8 ± 12.5 months (median=38.0, range=18-60 months). Problem items for the 815 (47.7% females) children studied were rated either by mothers (80.7%), fathers (4.2%) or for 15.1% by other primary caregivers (Table 1A). Most children had multiple siblings as well as caregiving house helpers other than their mothers, and were exposed at home to spoken languages other than Arabic. Fifty-three percent of the children were attending nursery or kindergarten schools (Table 1B).

| Gender (%) | |

|---|---|

| Girls | 47.7 |

| Boys | 50.3 |

| Age (mo) | |

| Mean ± SD | 38.8 ± 12.5 |

| Median | 38.0 |

| Range | 18-60 |

| Associated illnesses, number of children (%) | |

| Atopy | 20 (2.5) |

| Inborn error of metabolism | 5 (0.6) |

| Speech problem | 4 (0.4) |

| Abnormal growth | 2 (0.2) |

| Blood problem | 3 (0.4) |

| Alopecia aerata | 2 (0.2) |

| Cardiac problem | 2 (0.2) |

| Renal problem | 2(0.2) |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 1 (0.1) |

| Autism spectrum | 1 (0.1) |

| Autism+Attention deficit hyperactivity | 1 (0.1) |

| Mothers’ employment status | |

| Housewives | 249 (31%) |

| Teachers | 60 (7%) |

| Students | 23 (3%) |

| Healthcare | 18 (2%) |

| Social workers | 5 (0.6%) |

| Unspecified workforces | 460 (56%) |

| Fathers’ employment status | |

| Police | 270 (33%) |

| Governmental sector | 163 (20%) |

| Retirements | 16 (2%) |

| Engineers | 15 (1.8%) |

| Teachers | 3 (0.4%) |

| Unspecified workforces | 348 (43%) |

| Residence £ | |

| Urban | 365 (45%) |

| Semi-urban | 300 (37%) |

| Rural | 150 (18%) |

Table 1A. Sample characteristics (n=815)*. *Nine hundred sixty-one children were enrolled in this study. Fifty-seven (5.9%) children were not included in the analysis for missing age, 44 (4.6%) for age >60 mo, 14 (1.5%) children for age ˂18 mo and 31 (3.2%) for nationality

Thus, the analysis was performed on the remaining 815 (84.8%) Emirati children

£Sample distribution was proportional to the Emirati population residing in Abu Dhabi

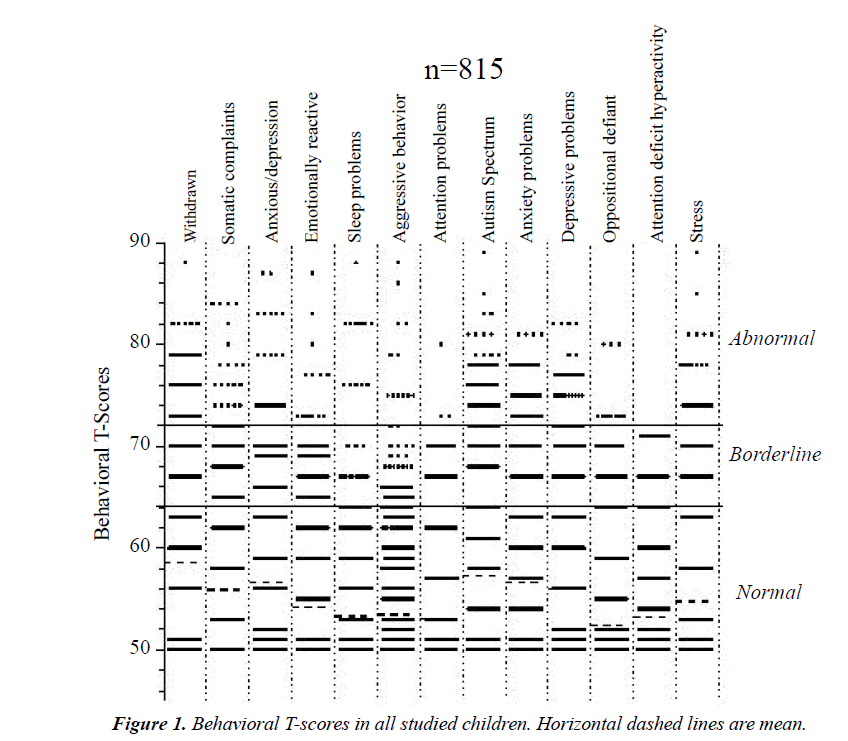

The results are summarized in Tables 1-3 and Figure 1. The prevalence of behaviors internalizing problem items was 8.3% (mainly uncommunicative social withdrawal, somatic complaints and anxiety/depression). Behaviors externalizing problem items (most notably aggression) were observed in 1.7% of children, autism spectrum in 13.6%, anxiety in 9.6%, and depression in 8.0% (Table 2). Girls significantly displayed fewer internalizing problem items than boys (6.7% vs. 9.9%, p=0.04) and, although they had fewer externalizing problem items than boys, the difference was not statistically significant (1.3% vs. 2.1%, p=0.1).

| Mother education | |

|---|---|

| Less than high school | 21 (13%) |

| High school | 59 (38%) |

| College | 73(46%) |

| University | 4 (3%) |

| Father education | |

| Middle school | 28 (18%) |

| High school | 55 (35%) |

| College | 64 (41%) |

| University | 10 (6%) |

| Consanguinity | |

| First cousins | 35 (23%) |

| Second cousins | 30 (19%) |

| None | 89 (58%) |

| No. of siblings | |

| 0 | 1 (<1%) |

| 1 | 22 (14%) |

| 2 | 37 (24%) |

| 3 | 33 (21%) |

| 4 | 22 (14%) |

| ≥5 | 42 (27%) |

| No. of house helpers | |

| 0 | 50 (32%) |

| 1 | 58 (37%) |

| 2 | 29 (19%) |

| 3 | 14 (9%) |

| 4 | 4 (2%) |

| ≥ 5 | 2 (1%) |

| Caregivers other than mother | |

| No | 41 (28%) |

| Yes (family member) | 18 (12%) |

| Yes (house helper) * | 89 (60%) |

| No. of spoken languages at home ** | |

| Arabic+English+Another language | 13 (9%) |

| Arabic+English | 104 (69%) |

| Arabic only | 33 (22%) |

| Child at school | |

| No | 74 (47%) |

| Nursery | 19 (12%) |

| Kindergarten | 64 (41%) |

Table 1B. Sample characteristics (n=157). Values are number (%) of participants. *Mostly from Indonesia, Ethiopia, Philippine and Bangladesh

**English was the predominant other language

Missing data were because of incomplete responses.

Sixty-eight (8.3%) children had internalizing problem items. Fourteen (1.7%) had externalizing problem items of whom 13 (1.6%) had internalizing symptoms as well (Table 2). The distribution of problem behaviors across the different age groups showed that the odds of abnormal oppositional defiant symptoms decreased by 4.2% when age increased by one month and the odds of an abnormal attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms increased by 5.3% when age increased by one month (Table 3).

The number of externalizing symptoms increased linearly with increasing T-scores for the internalizing emotionally reactive (R2 ≥ 0.965), anxiety depression (R2 ≥0.753), somatic complaints (R2 ≥0.928) and withdrawn behavior (R2 ≥ 0.930), Figure 1S – Panel A. Similarly, the number of internalizing symptoms also increased linearly with increasing T-scores for externalizing aggression (R2 ≥ 0.925), attention (R2 ≥ 0.816) and sleep (R2 ≥ 0.968), Figure 1S – Panel B. However, the linear increase was twice as steep externalizing symptoms (Figure 1S – Panel A) compared with the T-scores for externalizing symptoms vs. number of internalizing symptoms (Figure 1S – Panel B), 9.1 ± 1.7 vs. 4.7 ± 1.4 (p=0.057).

| Abnormal | Borderline | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL Syndrome Scale ? Internalizing Domain | |||

| Withdrawn | 123(15.1) | 65 (8.0) | |

| Somatic complaints | 52 (6.4) | 82 (10.1) | |

| Anxious/depression | 47 (5.8) | 80 (9.8) | |

| Emotionally reactive | 27 (3.3) | 70 (8.6) | |

| Internalizing problem items | 68 (8.3) | 78 (9.6) | |

| CBCL Syndrome Scale ? Externalizing Domain | |||

| Sleep problems | 18 (2.2) | 10 (1.2) | |

| Aggressive behavior | 18 (2.2) | 32 (3.9) | |

| Attention problems | 12 (1.5) | 23 (2.8) | |

| Externalizing problem items | 14 (1.7) | 30 (3.7) | |

| CBCL DSM-Oriented Scale | |||

| Autism spectrum | 111(13.6) | 30 (3.7) | |

| Anxiety problems | 78 (9.6) | 49 (6.0) | |

| Depressive problems | 65 (8.0) | 39 (4.8) | |

| Oppositional defiant | 18 (2.2) | 15 (1.8) | |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity | 12 (1.5) | 24 (2.9) | |

Table 2. Prevalence of the abnormal or borderline symptoms (n=815).

Values are number (%) of children

Some children had more than one abnormal or borderline symptom.

The distribution of internalizing and externalizing problem items among the DSM diagnoses is shown in Table 3 and Figures 2S and 3S. Fifty-five (6.7%) children had only abnormal internalizing problem items, one (0.1%) child had only abnormal externalizing problem items and 13 (1.6%) children had both. Interestingly, some children with DSM diagnoses had either normal or borderline internalizing or externalizing problem items (Figures 2S and 3S).

Of the 284 children who had abnormal (T-scores ≥ 70) DSMoriented scale, 97 (34%) had only one DSM problem, 82 (29%) had two, 72 (25%) had three, 28 (10%) had four and 5 (2%) had five DSM problems.

Discussion

This study assessed the prevalence of behavioral and emotional problems in preschool children, based on their parents' report questionnaire, using the standardized CBCL/1.5-5 tool [6,7] (Figure 1S). The prevalence of internalizing problem items was 8.3% and of externalizing problem items 1.7%. Children with borderline T-scores (Table 2) also require follow-up assessments similar to those in the abnormal group. From these results in the small sample of preschool children studied, the need for implementing childhood behavioral screening and intervention programs for the entire community becomes imperative.

Behavioral and emotional difficulties, often neglected in young children, will manifest as conduct disorders in adults [14]. Furthermore, parents often trace their children’s conduct (e.g. fear, aggression, tantrums, hyperactivity and inattention) to their preschool years [15]. Therefore, early recognition of these symptoms in toddlers offers opportunities to address family education, behavioral modification as well as liaison with schools [16]. Affected children need to be followed closely and referred for further assessments and for treatment, when necessary [17,18].

| Age (mo) (n) | 18-24 (98) | 24-30 (136) | 30-36 (86) | 36-42 (142) | 42-48 (92) | 48-54 (142) | 54-60 (119) | Coefficient | P * | Odds Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL Syndrome Scale ? Internalizing Domain | |||||||||||

| Withdrawn | 9 (9.9) | 22 (17.2) | 11 (14.1) | 27 (20.1) | 8 (9.3) | 27 (21.9) | 19 (17.3) | 0.012 | 0.1 | 1.012 | |

| Somatic complaints | 9 (9.8) | 17 (5.8) | 3 (3.7) | 8 (6.5) | 3 (3.6) | 10 (7.8) | 12 (11.3) | 0.012 | 0.3 | 1.012 | |

| Anxious/depression | 4 (4.5) | 9 (7.3) | 6 (7.3) | 10 (7.8) | 5 (6.0) | 7 (5.8) | 6 (5.4) | 0.003 | 0.8 | 1.003 | |

| Emotionally reactive | 3 (3.5) | 3 (2.4) | 3 (3.8) | 4 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 10 (7.6) | 4 (3.7) | 0.018 | 0.2 | 1.019 | |

| Internalizing problem items | 8 (9.1) | 11 (8.8) | 6 (7.6) | 14 (11.1) | 3 (3.5) | 17 (13.5) | 9 (8.3) | 0.006 | 0.6 | 1.006 | |

| CBCL Syndrome Scale ? Externalizing Domain | |||||||||||

| Sleep problems | 2 (2.1) | 5 (3.7) | 3 (3.5) | 5 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.1) | 0 (0) | -0.029 | 0.1 | 0.972 | |

| Aggressive behavior | 2 (2.1) | 3 (2.3) | 3 (3.6) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (3.6) | 2 (1.7) | 0.004 | 0.8 | 1.004 | |

| Attention problems | 1 (1.0) | 3 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.1) | 2 (1.7) | 0.011 | 0.6 | 1.011 | |

| Externalizing problem items | 2 (2.0) | 3 (2.3) | 2 (2.4) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (1.7) | 0.002 | 0.9 | 1.002 | |

| CBCL DSM-Oriented Scale | |||||||||||

| Autism spectrum | 14 (14.6) | 15 (11.7) | 9 (10.7) | 23 (16.8) | 9 (9.8) | 24 (17.8) | 17 (15.0) | 0.010 | 0.2 | 1.010 | |

| Anxiety problems | 10 (10.1) | 13 (10.0) | 12 (14.3) | 11 (8.7) | 4 (4.6) | 18 (13.3) | 10 (8.8) | -0.001 | 0.9 | 0.999 | |

| Depressive problems | 5 (5.2) | 9 (6.9) | 5 (6.3) | 16 (12.1) | 4 (4.6) | 17 (12.4) | 9 (7.9) | 0.014 | 0.2 | 1.015 | |

| Oppositional defiant | 4 (4.1) | 4 (3.0) | 5 (5.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0) | -0.043 | 0.031 | 0.958 | |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (2.8) | 4 (3.3) | 0.052 | 0.033 | 1.053 | |

Table 3. Prevalence of the abnormal symptoms by age group (n=815).

Values are number (%) of children

*Simple logistic regression (likelihood ratio test).

Studies have already demonstrated that routine healthcare visits are optimal opportunities for identifying young children at risk of autism and other significant problem behaviors [17,18]. As a result, many “parent-report child behaviorrating scales” are already available for outpatient clinical use [17]. The scale which was used in this study (CBCL/1.5- 5) has already been previously validated and also used as a screening instrument in our community [6,7].

Internalizing problem items were statistically more prevalent in boys than in girls (9.9 vs. 6.7, p=0.04). This confirms previous reports in which externalizing problem items were also more prevalent in boys than in girls, but that was not statistically significant (2.1 vs. 1.3, p=0.1), Table 1S (Supplementary Material) [19,20].

In 1995, a study from the same city showed the prevalence of behavior problems (including emotional, conduct and undifferentiated disorders) in children between the ages of 5.4 and 16.6 years was 13.5% (16.3% in boys and 10.2% in girls) [9]. The authors concluded that “a considerable proportion of young children manifest signs of behavior disorders in primary school and that primary school child in this city and comparable areas, should be screened for behavior disorders. Affected children will require confirmation of the presence or absence of behavior disorders by health professionals” [9]. Two decades later, our results from the same city (Tables 2S and 3S) are consistent with the above conclusion and reinforce the resulting recommendations.

It is important to recognize that behavioral screening instruments, which depend on information provided by parents, are not a substitute for a rigorous evaluation by a specialist. Further assessments should always include thorough personal and familial histories. Once a problem is confirmed, a clear plan of management should be promptly instituted.

In view of the diversity of the childhood behavioral and emotional problems associated with a wide range of potential comorbidities, specific questions should always include assessment of cognitive development, language acquisition and other learning skills. Prior neurologic, psychiatric or traumatic history or a family history of behavioral or emotional difficulties should also be considered.

In summary, the profiles of behaviors with externalizing and internalizing symptoms found in this study support the need for implementing regular toddler behavioral screening and early interventional treatment programs for affected young children in our community.

Acknowledgement

We thank the participating families and AHS staff for their support of this work. We are also grateful to Mrs. Sania Al- Hamad for staff training and collecting data.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding

This work was supported by the United Arab Emirate University and the Ambulatory Health Services of Abu Dhabi. There is no conflict of interest. For the remaining authors none were declared. The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committees for Human Research of the Medical District.

References

- Bayer JK, Ukoumunne OC, Mathers M, et al. Development of children's internalising and externalising problems from infancy to five years of age. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46:659-68.

- Aebi M, Winkler Metzke C, Steinhausen HC. Accuracy of the DSM-oriented attention problem scale of the child behavior checklist in diagnosing attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Atten Disord. 2010;13:454-63.

- Egger HL, Angold A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: presentation, nosology and epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:313-37.

- Basten M, Tiemeier H, Althoff RR, et al. The stability of problem behavior across the preschool years: An empirical approach in the general population. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2016;44:393-404.

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:57-87.

- Ivanova MY, Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, et al. Preschool psychopathology reported by parents in 23 societies: Testing the seven-syndrome model of the child behavior checklist for ages 1.5-5. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:1215-24.

- Rescorla LA, Achenbach TM, Ivanova MY, et al. International comparisons of behavioral and emotional problems in preschool children: Parents' reports from 24 societies. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2011;40:456-67.

- Yunis F, Eapen V, Zoubeidi T, et al. Psychometric properties of the child behavior checklist/2-3 in an Arab population. Psychol Rep. 2007;100:771-6.

- Al-Kuwaiti MA, Hossain MM, Absood GH. Behaviour disorders in primary school children in Al Ain, United Arab Emirates. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1995;15:97-104.

- Eapen V, Mabrouk AA, Zoubeidi T, et al. Prevalence of pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children in the UAE. J Trop Pediatr. 2007;53:202-5.

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, et al. The infant-toddler social and emotional assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability and validity. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2003;31:495-514.

- Sterba S, Egger HL, Angold A. Diagnostic specificity and non-specificity in the dimensions of preschool psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:1005-13.

- Mesman J, Koot HM. Early preschool predictors of preadolescent internalizing and externalizing DSM-IV diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1029-36.

- Alakortes J, Kovaniemi S, Carter AS, et al. Do child healthcare professionals and parents recognize social-emotional and behavioral problems in 1 year old infants? Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016.

- Weitzman C, Edmonds D, Davagnino J, et al. The association between parent worry and young children's social-emotional functioning. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011;32:660-7.

- Kimball V. Social-emotional development: Quirky or time to worry? Pediatr Ann. 2016;45:e337-9.

- Jaspers M, de Winter AF, Buitelaar JK, et al. Early childhood assessments of community pediatric professionals predict autism spectrum and attention deficit hyperactivity.JAbnormal Child Psychol. 2013;41:71-80.

- Muratori F, Narzisi A, Tancredi R, et al. The CBCL 1.5-5 and the identification of preschoolers with autism in Italy. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2011;20:329-38.

- Hay DF. The gradual emergence of sex differences in aggression: Alternative hypotheses. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1527-37.

- Rutter M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Using sex differences in psychopathology to study causal mechanisms: Unifying issues and research strategies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44:1092-115.