- Biomedical Research (2013) Volume 24, Issue 3

Retrospective study of endoscopic nasal septoplasty.

Ali Maeed Al-Shehri1, Hany Mohamed Amin2, Ahmed Necklawy31Ear, Nose and Throat Division, Department of Surgery, College of Medicine, King Khalid University and Aseer Central Hospital, Abha, Saudi Arabia; Saudi Arabia

2Consultant, Saudi German Hospital-Aseer, Khamis Mushait, Saudi Arabia

3Muhayel Private Hospital, Muhayel, Saudi Arabia

- Corresponding Author:

- Ali Maeed Al-Shehri

Department of Surgery, College of Medicine

King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia

E-mail: alimaeedalshehri@yahoo.com; namas3@hotmail.com

Accepted Date: April 11 2012

Citation: Al-Shehri AM, Amin HM, Necklawy A. Retrospective study of endoscopic nasal septoplasty. Biomed Res- India; 2013; 24 (3): 337-340.

Abstract

This is a retrospective review of data of 70 patients who underwent endoscopic nasal septoplasty . The case records of 70 patients who underwent endoscopic septoplasty during the period from January 2009 to December 2011 at the Saudi German Hospital, Aseer Region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia were reviewed. Patients had septal deviation and symptomatic nasal obstruction for at least 3 months, and medical management had failed. Preoperatively, nasal endoscopic findings were septum deviations (34 patients, 48.6%), spurs (30 patients, 42.9%) and septum deviations + spurs (6 patients, 8.6%). The most common presenting symptoms were nasal obstruction (55 patients, 78.6%), headache (42, 60%) and posterior nasal discharge (34, 48.6%), which improved significantly postoperatively. After the end of the follow up period of 6 months, there were no recorded immediate or late postoperative complications among all patients. Endoscopic nasal septoplasty is an effective technique that can be performed safely with a significant postoperative improvement in patient’s symptoms and minimal or no postoperative complications.

Keywords

Endoscopic nasal septoplasty; Nasal obstruction, Septum deviation

Introduction

Nasal obstruction is the most common symptom in ENT practice and septum deviation is the most common cause of nasal obstruction. The evaluation of septal deviation causing nasal obstruction depends heavily on physical examination and imaging [1]. Septoplasty is done to improve the nasal airway and relieve nasal obstruction to prevent the complications of nasal obstructions such as epistaxis, sinusitis, headache, obstructive sleep apnea. An ideal surgical correction of the nasal septum should satisfy the following criteria: should relieve the nasal obstruction, conservative, and should not produce iatrogenic deformity or septal perforation [2].

The progress of surgery on a deviated nasal septum witnessed great advances from radical removal of cartilage, and mucosa and radical removal of cartilage only by submucous resection to the modern techniques of septoplasty. It was first described by Cottle in 1947 as a treatment to correct nasal airway obstruction [3-5].

Endoscopic septoplasty is an attractive alternative to traditional septoplasty, whose primary advantage is the reduced morbidity and postoperative swelling in isolated septal deviations by limiting the dissection to the area of the deviation. In addition, endoscopic septplasty provides improved visualization, particularly in posterior septal deformities; improved surgical transition between septoplasty and sinus surgery; preservation of septum structure to provide adequate support of the nasal framework and to resist the effects of scarring. Moreover, it provides a significant clinical and an excellent teaching tool when used in conjunction with video monitors over traditional approaches [4].

Nasal endoscopy is an excellent method for the precise diagnosis of pathological abnormalities of the nasal septum. It permits the correlation between these abnormalities and the lateral nasal wall [6]. A directed approach using endoscopic septoplasty results in limited dissection and faster postoperative healing. Endoscopic septoplasty as a minimally invasive technique can limit the dissection and minimize trauma to the nasal septal flap under excel lent visualization. This is especially valuable for the patient having had previous nasal septal surgery [7,8].

In this study, we carried out a retrospective analysis of 70 patients who underwent endoscopic septoplasty from January 2009 to December 2011.

Patients and Methods

The files of 70 patients, who had undergone endoscopic septoplasty during the period January 2009 and December 2011 at the Saudi German Hospital, Aseer Region of Saudi Arabia, were studied. These files were reviewed for indications of endoscopic septoplasty, preoperative findings and postoperative complications. Included patients had septal deviation and symptomatic nasal obstruction for at least 3 months for which medical management had failed. Preoperatively, all patients were evaluated by nasal endoscopy and CT scan.

This study has been approved by the Research and Ethical Committee at the College of Medicine, King Khalid University (REC# 2012-10-04).

Technique of endoscopic septoplasty

Under endoscopic visualization with a 0 degree endoscope, topical nasal packing with oxymetazoline was applied for decongestion; 1% lidocaine with 1:200,000 epinephrine was injected subperichondrially along the septum. A vertical incision was made caudal to the deviation and for a broadly deviated septum, a standard Killian or hemi-transfixion incision was used. For more posterior isolated deformities, the incision was placed posteriorly in the immediate vicinity of the deformity. Mucoperichondrial flap elevation was performed with a Cottle elevator under direct endoscopic visualization with a 0-degree endoscope. The flap elevated was limited as it was raised from over the most deviated portion of the nasal septum, without disturbing the anterior normal septum. Septal cartilage was incised parallel but posterior to the flap incision and caudal to the deviation. If the deviation was found to be mainly bony, the incision was made at the bony-cartilaginous junction. The contra-lateral mucoperichondrial flap elevation was then performed. Flap elevation was continued bilaterally until the complete extent of the septal deformity had been dissected. Luc's forceps was used to excise the deviated portion. Once satisfactory correction had been achieved the nose irrigated with saline to clean the blood then the flap was repositioned .Insertion of nasal splint for one week used. Patients were discharged next day of surgery to be seen in the clinic after one week, then monthly for 6 months.

Results

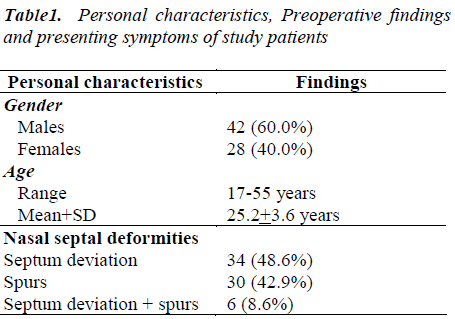

During the period from January 2009 till December 2011 a total of 70 patients (42 males and 28 females) underwent endoscopic septoplasty at the “Saudi German Hospital”. Their age ranged between 17 to 55 years (Mean+SD: 25.2 ± 3.6 years), as shown in Table 1.

Preoperatively, nasal endoscopic findings were septum deviations (34 patients, 48.6%), spurs (30 patients, 42.9%) and septum deviations + spurs (6 patients, 8.6%), as shown in Table 1.

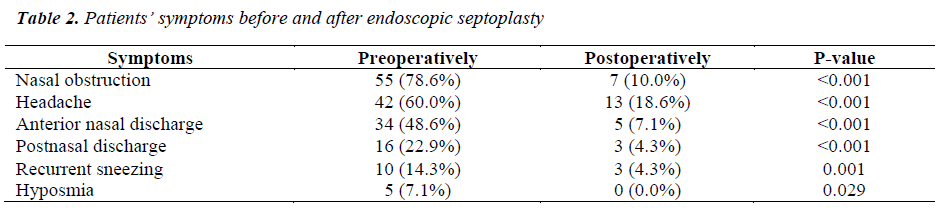

The most common presenting symptoms were nasal obstruction (55 patients, 78.6%), headache (42, 60%) and posterior nasal discharge (34, 48.6%), which improved significantly postoperatively, as shown in Table 2.

After the end of the follow up period of 6 months, there were no recorded immediate or late postoperative complications among all patients.

Discussion

This study revealed that all the included 70 patients had nasal septal deformities (i.e., septum deviation, spurs or combined). Postoperatively, there were significant improvements in all patients’ complaints. These findings may explain why the preferred surgical technique among patients was the endoscopic septaplasty, not the traditional headlight septoplasty.

Brennan et al. [9] noted that to obtain good results in septal surgery, there should be good exposure; safe elevation of flaps; and resection of the deviated part of the septum only. These could be obtained only by endoscopic septoplasty which has the advantage of a targeted approach to the specific septal problem, without the need for exposing excessive bone and cartilage, thereby improving healing time and decreasing tissue trauma.

Jain et al. [10] stated that applying the traditional technique of septoplasty improves the nasal obstruction but does not fulfill the above mentioned criteria in most instances. This is due to the difficulty to evaluate the exact pathology, especially in the posterior part of septum, and poor visualization. On the other hand, the nasal endoscopic technique allows precise preoperative identification of the septal pathology and associated lateral nasal wall abnormalities.

Lanza et al. [11] added that the rationale for developing an endoscopic technique from a traditional "headlight" approach came from the fact that during common nasal procedures, the surgeon's view is obstructed due to the narrowing caused by septal spurs or septal deviations. So, endoscopy usually enables the ENT surgeon to localize deviations, spurs and to remove them under direct vision, thus minimizing surgical trauma.

Jain et al. [10] stated that early reports of endoscopic septoplasty described several advantages associated with the technique, e.g., it makes easier for surgeons to see the tissue planes and it offers a better way to treat isolated septal spurs. Additionally, the endoscopic approach makes it possible for others to simultaneously observe the procedure on a monitor, making the approach useful in a teaching hospital.

The present study revealed that, after the end of the 6- months follow up period, there were no recorded postoperative complications among all patients. This finding is in full agreement with those of Park et al. [12], who observed that endoscopic septoplasty has much fewer complications compared with the conventional headlight septoplasty. They reported that the incidence of synechiae is significantly less in patients who underwent endoscopic septoplasty compared with those who underwent traditional septoplasty.

Similarly, the complication rates after endoscopic septoplasty were reported by Hwang et al. [7] to be 5%, and by Gupta et al. [3] to be 2.08%, while Nawaiseh and Al- Khtoum[13] reported no immediate postoperative complications in their series.

On the other hand, since the traditional approach to septoplasty involves headlight illumination, visualization through a nasal speculum, and surgical instruments that are different from those used during endoscopic procedures, these circumstances can be suboptimal when treating a narrow nose, or during approaching posterior deviation. Moreover, impaired visualization may predispose to nasal mucosal trauma, which can compromise endoscopic visualization during sinus surgery, thus leading to much higher rates of postoperative complications [10].

Paradis and Rotenberg [14] stated that the endoscopic approach for septoplasty is superior to the traditional approach for the correction of septal deviation. Moreover, Sautter and Smith[15] concluded that nasal endoscopy is an excellent tool for outpatient surveillance following septoplasty during the initial postoperative healing period and beyond. Moreover.

In conclusion, endoscopic septoplasty is an effective technique that can be performed safely with a significant postoperative improvement in patient’s symptoms and minimal or no postoperative complications. It facilitates accurate identification of the pathology, and it is associated with significant reduction in patient’s morbidity in the postoperative period.

References

- Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI, McGuirt W. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38:553-562.

- BanwellPE, Musgrave M. Topical negative pressure therapy: mechanisms and indications. Int Wound J 2004;1:95–106.

- Morykwas MJ. Faler BJ, Pearce DJ, Argenta LC. Effects of varying levels of subatmospheric pressure on the rate of granulation tissue formation in experimental wounds in swine. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;47:547-551.

- Scheufler O, Peek A, KaniaNM, Exner K. Problemadapted application of vacuum occlusion dressings: case report and clinical experience. Eur J Plast Surg 2000;23:386-390.

- Willy C, Voelker HU, Engelhardt M. Literature on the subject of vacuum therapy review and update. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2007;1:33-39.

- Scherer LA, Shiver S, Chang M, Meredith JW, Owings JT. The vacuum assisted closure device: a method of securing skin grafts and improving graft survival. Arch Surg. 2002;137:930-933.

- Subramonia S, Pankhurst S, Rowlands BJ, Lobo DN. Vacuum-assisted closure of postoperative abdominal wounds: a prospective study. World J Surg. 2009;33:931-937.

- Teixeira PG, Salim A, Inaba K, Brown C, Browder T, Margulies D, Demetriades D. A prospective look at the current state of open abdomens. Am Surg 2008;74:891-897.

- Marinis A, Gkiokas G, Anastasopoulos G, Fragulidis G, Theodosopoulos T, Kotsis T, Mastorakos D, Polymeneas G, Voros D Surgical techniques for the management of enteroatmospheric fistulae. Surg Infect. 2009;10:47-52.

- Miller PR, Meredith JW, Johnson JC, Chang MC. Prospective evaluation of vacuum-assisted fascial closure after open abdomen: planned ventral hernia rate is substantially reduced. Ann Surg 2004;239:608-614.

- Antony S, Terrazas S. A retrospective study: clinical experience using vacuum-assisted closure in the treatment of wounds. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;968:1073-1077.

- Lambert KV, Hayes P, McCarthy M. Vacuum assisted closure: a review of development and current applications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29:219-226.

- Greene AK, Puder M, Roy R, Arsenault D, Kwei S, Moses MA, Orgill DP. Microdeformational wound therapy: effects on angiogenesis and matrix metalloproteinases in chronic wounds of 3 debilitated patients. Ann Plast Surg 2006;56:418-422.

- Kamolz LP, Andel H, Haslik W, Winter W, Meissl G, Frey M. Use of subatmospheric pressure therapy to prevent burn wound progression in human: first experiences. Burns 2004;30:253-258.

- Obdeijn MC, de Lange MY, Lichtendahl DH, de Boer WJ. Vacuum-assisted closure in the treatment of poststernotomy mediastinitis. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;68:2358-2360.

- De Franzo AJ, Marks MW, Argenta LC, Genecov DG. Vacuum-assisted closure for the treatment of degloving injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:2145-2148.

- Barker DE, Green JM, Maxwell RA, Smith PW, Mejia VA, Dart BW, Cofer JB, Roe SM, Burns RP. Experience with vacuum pack temporary abdominal wound closure in 258 trauma and general and vascular surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:784-793.

- Rao M, Burke D, Finan PJ, Sagar PM. The use of vacuum assisted closure of abdominal wounds: a word of caution. Colorectal Dis 2007;9:266-268.

- Labler L, Zwingmann J, Mayer D, Stocker R, Trentz O, Keel M. V.A.C. abdominal dressing system. Eur J Trauma 2005;5:488-494.

- Starr-Marshall K. Vacuum-assisted closure of abdominal wounds and entero-cutaneous fistulae: the St Marks experience. Colorectal Dis 2007;9:573.

- Lambert KV, Hayes P, McCarthy M. Vacuum assisted closure: a review of development and current applications. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29:219-26.

- Webb LX. New techniques in wound management: vacuum-assisted wound closure. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:303-11.

- Argenta LC, Morykwas MJ, Marks MW, De Franzo AJ, Molnar JA, David LR. Vacuum-assisted closure: state of clinic art. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7 Suppl):127S-142S.