Case Report - Otolaryngology Online Journal (2016) Volume 6, Issue 3

Pyriform Sinus Fistula

Vijay Abraham*, Anjali Lepcha, Betty Simon, BS Chandran

Department of Surgery Unit 3, Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, Tamilnadu, India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Vijay Abraham

Department of Surgery Unit 3, Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, Tamilnadu, India

E-mail: vabraham@cmcvellore.ac.in

Received date: April 06, 2016; Accepted date: May 18, 2016; Published date: May 23, 2016

Abstract

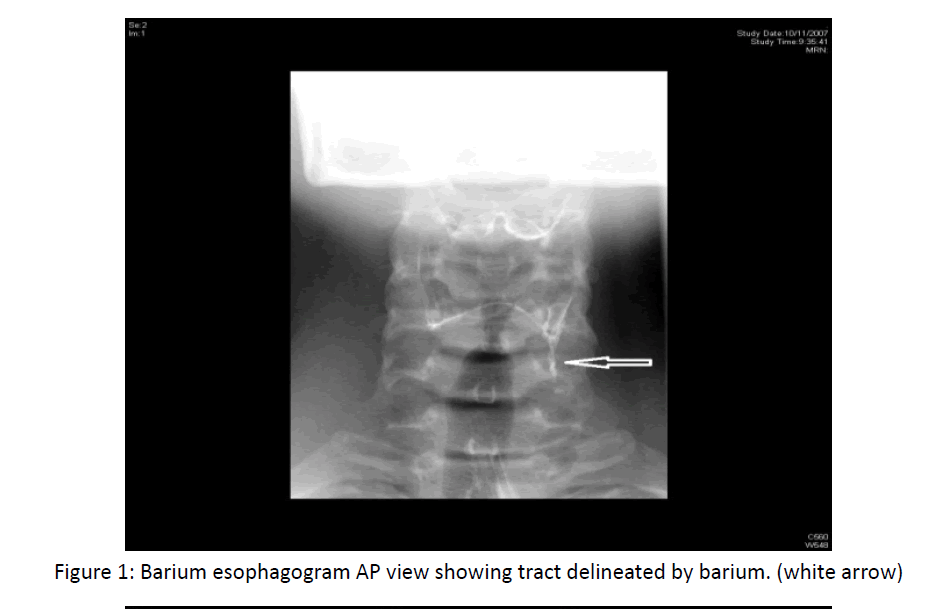

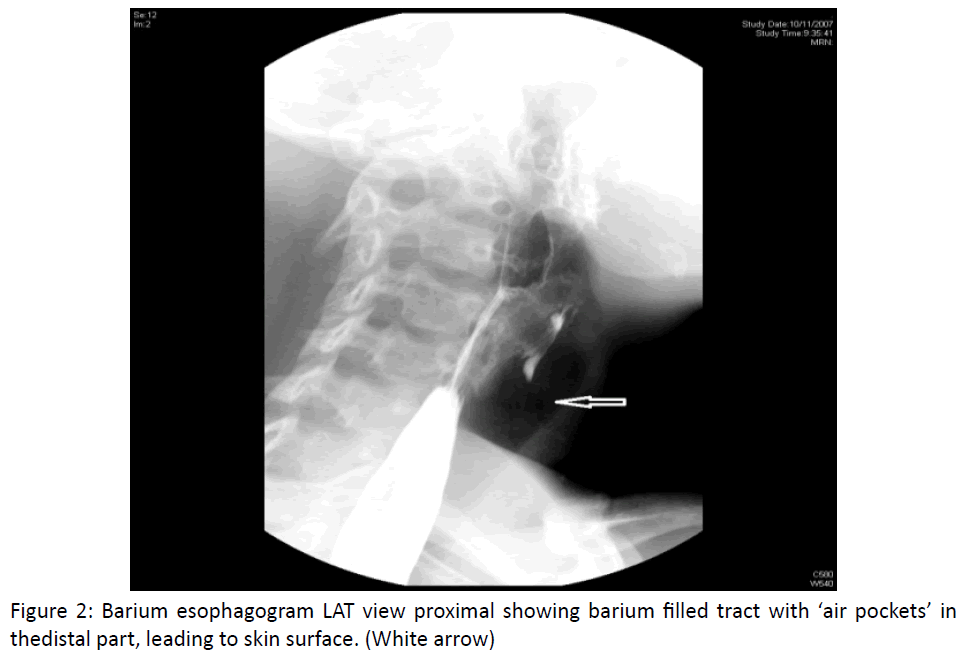

Pyriform sinus fistula is the rarest of the cervical branchial anomalies. A recurrent left sided lower neck infection may be the only clue to this elusive entity. The ambiguity of the presentation, its diagnosis, delineation of its possible anatomical course and treatment options are highlighted in this review article.

Abstract

Traumatic injuries are very common in oral cavity and involve primarily the soft palate. Traumatic injuries involving the hard palate in adults are rare. Hard palate perforation secondary to animal trauma is a rare entity. This is an unusual case where a 50 yrs old male presented with midline hard palate injury by horn of a bull. The perforation was repaired using palatoplasty and patient had no complication postoperatively. This case report reviews other unusual causes of palatal perforation, mechanism of bull horn injuries and treatment options for such defects.

Keywords

Palate, Perforation, Traumatic

Introduction

Palatal perforation either acute or chronic is rarely caused by trauma. Penetrating trauma to the head and neck accounts for 1% to 2% of pediatric trauma admissions. Children have a propensity to place objects in their mouths, which leaves them at risk of trauma to the oral cavity. On the contrary palatal trauma in adults is rare [1].

Bull-horn wounds are incisive and contusive, they have special Characteristics [2]

• The entry opening is usually small and surrounded by an erosion zone. It also may not correlate with the gap in the aponeurosis.

• One or more in-depth tracts may be present, usually with important muscular destruction.

• These wounds are contaminated, and multiple foreign bodies may found at the bottom of the wound tract, including cloth fragments, dirt, and horn chips.

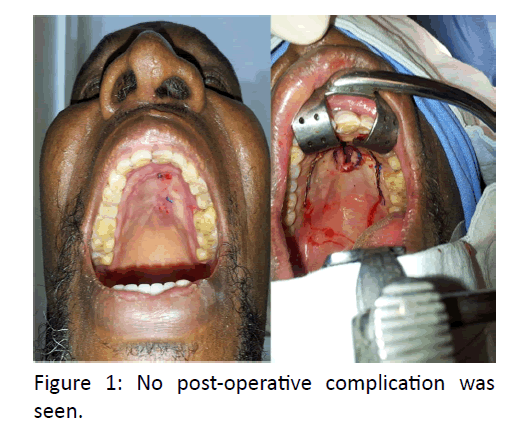

This contaminated wound has a high chance of failure in primary closure. Review of important causes of palatal fistula indicate Developmental causes being the most common cause, occur due to failure of fusion of palatal shelves by 6th week of prenatal life. Maternal alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, deficiency of folic acid, teratogenic drugs and viruses are some of the known environmental factors leading to cleft palate [2] (Figure 1).

Various infectious and chronic granulomatous conditions are known to cause palatal perforation like leprosy, tertiary syphilis, tuberculosis, actinomycosis, histoplasmosis, and blastomycosis. Autoimmune conditions including sarcoidosis, Wegner’s and Crohn’s disease also lead to palatal perforation [3].

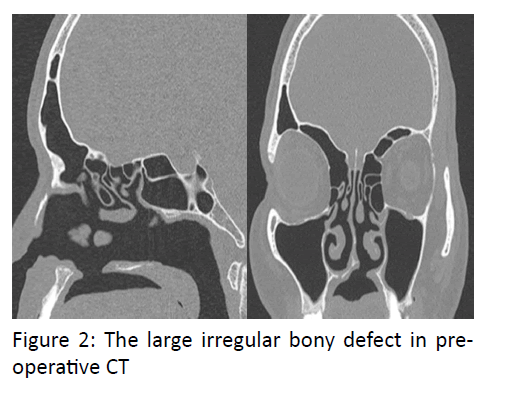

Malignancy of minor salivary gland tumor like adenoid cystic carcinoma also leads to palatal perforation [4]. Tumors’ from maxilla and nose also contributes to this either due to rapid spread leading to bulge in palatal area and later on perforation or sometimes perforation occur as a part of treatment5. Cocaine is a proven drug leading to perforation, other drugs involving the palate includes heroine and nicotine [6] (Figure 2).

Perforation might occur following a surgical procedure done for tumor removal or may be following intubation. Literature also describes role of rhinolith leading to perforation [7]. Aim of presenting this case is to emphasize the rare cause of palatal injury being animal.

Case Report

A 50 yrs old male from Nigeria presented to ENT OPD with a defect in hard palate since 6 months, which occurred owing to injury by the horns of bull. Patient also had laceration involving lips and right side ala of nose. Patient had difficulty while eating and change in speech. The patient was taking treatment from the primary health centre in Nigeria, where he underwent repair for the laceration but no intervention was done for the palatal wound. Examination revealed nasal speech, an oval palatal fistula with irregular margins measuring 3 x 1 cm; extending anteriorly up to the rughae area and posteriorly up to the canines. No signs of inflammation noted. CECT oral cavity revealed area of defect at the anterior part of hard palate.

Patient was taken up for V-Y Palatoplasty and intra operatively the bony defect was found to be 5 x 5 cm. The defect was then repaired in 3 layers using PDS suture for nasal layer and 4.0 vicryl for muscle and mucosa, and patient was allowed liquids orally next morning. Due to the large irregular bony defect in pre-operative CT, consent for bone grafting was also taken but intra operatively the closure was adequate.

Discussion

Palate contributes to an important part of oral cavity, the defect of which leads to nasal regurgitation of food, recurrent nose and ear infections and nasal speech.

It comprises of the palatine part of palatine process of maxilla covered by palatine muscles and mucosal layer.

Pathologies affecting palate can be congenital or acquired. Acquired causes include idiopathic or due to traumatic, infectious, malignancy related, granulomatous disease.

Case presented here is of interest as it is caused by trauma by horns of animal (bull). It is important to understand the complex mechanism causing the wound, as the result of the interaction of various distinct forces. The depth is dependent on the force of penetration of the bull´s horn into the body (which is the result of the animal´s weight and speed). There is an additional force because of the effect of the bull´s strong neck muscles when it raises its horns. This force causes upward tears at right angles to the ground. If the injured person is lifted, his body weight exerts an opposite force. Finally, when the patient´s body is lifted and suspended by the bull´s horns, it is in an unstable balance, which, depending on the location of the center of gravity relating to the horn, causes a rotational movement (with ensuing tears of arteries, veins, and nerves), combined with the animal´s efforts to disengage the person´s body [8].

Cases of traumatic perforation have been reported in literature. Hwang and Kim reported a case of submucosal cleft palate in 27 yr old women because of ingestion of hot food (Thermal injury). Perforation and midline notching at the posterior edge of the hard palate was seen noted [9]. A case of 69 years male patient was reported by Macleod in which perforation of the hard palate secondary to pressure atrophy was noted [10]. Ozul et al. [11] reported a case in which perforation of hard and soft palate is seen after a long intubation period. A case of palatal perforation in a 36-year-old female patient treated for empyema of maxillary sinus was reported by Pegler [12]. Other non-traumatic acquired causes presenting as palatal perforation should include infections (syphilis, leprosy, tuberculosis, diphtheria, mucormycosis, actinomycosis) tantrum oris, mechanical trauma, intranasal cocaine abuse, malignancies (especially nasal T cell lymphomas, carcinoma, melanoma), collagen vascular diseases (Wegener’s granulumatosis, systemic lupus erythematosus), sarcoidosis and idiopathic cause such as midline non-healing granuloma [13]. This patient was operated 6 months after the injury. This was sufficient time for optimal wound healing and contraction of fistula and union of adjacent maxilla facial bones. Pre-operative CT scan helps in determining the extent of surgery required and to consent the patient for possible bone grafting.

The treatment options comprise sealing of the defect, either surgically or with a removable obturator, once the lesion has been seen to remain stable. The surgical technique is chosen according to the location and dimension of the lesion, the presence of infections and the general patient conditions.

For reconstruction of the defect, the literature describes surgical techniques like primary closure, use of local pedicled flaps, lingual grafts, temporal muscle flaps, oral adipose tissue grafting, von Langenbeck technique, Furlow double opposing Z palatoplasty, Veau-Wardill-Kilner or VY pushback palatoplasty. In case of extensive lesions, free microvascular flap ie. radial forearm free flap 15 is indicated, with or without simultaneous bone transfer [14,15].

The literature also describes the resolution of small or medium-sized defects using a Le Fort I osteotomy and bilateral adipose flap of the Bichat bulla, in those cases where a temporal or microvascularized flap is contraindicated [16]. Anterior hard palate perforation are better dealt with von lagenbeck technique or its modifications , V Y pushback palatoplasty and posterior soft palate ones by furlow double opposing Z palatoplasty. Each of these techniques has their advantages and different failure rates depending on site of perforation and extent of perforation. This case was done by VY pushback palatoplasty without complications of VPI or fistula.

The use of prosthetic obturators as a solution to situations that pose social problems for the patient is often indicated in cases characterized by palatal communications secondary to highly mutilating surgery. These obturators may be offered as an alternative for patients with palatal perforations who do not wish to undergo surgery, in those cases where the cost/benefit ratio is not favorable, in patients who cannot or do not wish to abandon the habit, or as a temporary measure before surgical treatment [14,17].

Such obturators avoid nasal reflux, facilitating correct swallowing and sufficient speech performance. The only contraindication to such devices is patient tolerance of the obturator, since in some cases the obturator size required to fully seal the defect can cause nausea [17].

Conclusion

Traumatic injuries to maxillofacial region are quite common but this report presents a unique type of traumatic injury causing perforation of palate.

References

- Cooper A, Barlow B, Niemirska M, Gandhi R (1987) Fifteen years’ experience with penetrating trauma to the head and neck in children. JPediatr Surg 22: 24-27

- Bull- Horn injuries: a nine year experience ( article in Spanish) Our Surgical Diseases Around the World column, guest edited by Walter J. Burdette, M.D., Ph. D., of Houston, Texas, examines the geographic distribution of disease and the varying treatment modalities around the world.

- Amaratunga NA (1989) A study of etiologic factors for cleft lip and palate in Sri Lanka. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 47: 7-10.

- Karabulut AB, Kabakas F, Berköz O, Karakas Z, Kesim SN (2005) Hard palate perforation due to invasive aspergillosis in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J PediatrOtorhinolaryngol 69: 1395-1398.

- Ferrazzo KL, Schneider PP, Shinohara EH (2011) An unusual case of adenoid cystic carcinoma with hard palate perforation. Minerva Stomatol 60: 83-86.

- Chaudhary SV, Karnik ND, Sabnis GR, Patil MV, Bradoo RA (2011) Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma presenting as palatal perforation with oronasal fistula. J Assoc Physicians India 59: 112-114.

- Silvestre FJ, Perez-Herbera A, Puente-Sandoval A, Bagán JV (2010) Hard palate perforation in cocaine abusers: a systematic review. Clin Oral Investig 14: 621-628.

- Pinto LS, Campagnoli EB, de Souza Azevedo R, Lopes MA, Jorge J (2007) Rhinoliths causing palatal perforation: case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral RadiolEndod 104: e42-e46.

- Herranz F, Hernandez C (1987) Heridas genitourinarias por asta de toro: A propósito de tres casos.ActasUrolEsp 11:214-217

- Hwang K, Kim YS (2010) Perforation in submucous cleft palate due to thermal injury. J Craniofac Surg 21: 280-281.

- Macleod AL (1927) Perforation of hard palate. Proc R Soc Med 20: 1096.

- Ozgul S, Tezel E, Numanoglu A (2005) Palatal perforation after long intubation period. Eur J Plast Surg 27: 335-337.

- Pegler LH (1910) Traumatic (post-operative) Perforation through the Hard Palate, communicating with the Floor of Left Nasal Fossa and Maxillary Antrum. Proc R Soc Med 3: 146.

- Goodger NM, Wang J, Pogrel MA (2005) Palatal and nasal necrosis resulting from cocaine misuse. Br Dent J 198:333-334.

- Di Cosola M, Turco M, Acero J, Navarro-Vila C, Cortelazzi R (2007) Cocaine-related syndrome and palatal reconstruction: report of a series of cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 36:721-727.

- Pelo S, Gasparini G, Di Petrillo A, Tassiello S, Longobardi G, Boniello R (2008) Le Fort I osteotomy and the use of bilateral bichat bulla adipose flap: an effective new technique for reconstructing oronasal communications due to cocaine abuse. Ann Plast Surg 60: 49-52.

- Genden EM, Wallace DI, Okay D, UrkenML (2004) Reconstruction of the hard palate using the radial forearm free flap: indications and outcomes. Head Neck 26: 808-814.