Research Article - Biomedical Research (2017) Volume 28, Issue 5

Prognostic value of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in advanced gastric cancer patients undergoing first-line chemotherapy with DCF: a retrospective study

Yanrong Wang, Yang Chen, Yan Shi, Hui Mao and Guanghai Dai*The Second Department of Oncology, Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital, Beijing 100853, PR China

- *Corresponding Author:

- Guanghai Dai

The Second Department of Oncology

Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital

Beijing, PR China

Accepted on October 13, 2016

Abstract

Objective: In this study, we investigated the correlation between the degree and timing of chemotherapyinduced neutropenia (CIN) caused by the DCF (docetaxel-platinum-fluorouracil) regimen as first-line chemotherapy and the survival of patients with advanced gastric cancer.

Methods: We retrospectively analysed 110 patients diagnosed with advanced gastric cancer between 2007 and 2012 at our hospital who received 2 to 6 cycles of the DCF regimen as first-line chemotherapy. According to the CTCAE 4, CIN is categorized as G0, G1/2, G3, or G4. We stratified all patients into the following two groups based on the onset (timing) of CIN: early onset and late onset.

Results: A total of 110 patients were included in this study. Among these patients, 15 (13.6%) did not exhibit CIN (grade 0), 54 (49.1%) experienced mild CIN (grade 1-2), 22 (20.0%) developed moderate CIN (grade 3), and 19 (17.3%) suffered from severe CIN (grade 4) during the first line of chemotherapy. The median progression-free survival (PFS) of the 110 patients was 6.0 months (95% CI: 5.5~6.6 months), and the median overall survival (OS) of the 110 patients was 12.7 months (95% CI: 11.2~14.2 months). According to a multivariate analysis, the hazard ratio of death was 0.59 (95% CI: 0.49-0.72, P=0.005) for patients with G1/2 CIN, 0.71 (95% CI: 0.52-0.90, P=0.001) for patients with G3 CIN, and 0.74 (95% CI: 0.46-0.93, P=0.023) for patients with G4 CIN compared with patients who did not suffer from neutropenia (G0).

Conclusion: Patients who experienced G1/2 CIN had a more favourable treatment response and prognosis, whereas the absence of CIN predicted poor efficacy and survival, which may occur because the dose was ineffective. In addition, patients with G4 CIN did not exhibit better efficacy and prognosis, and the clinical outcomes were better for early-onset neutropenia than for late-onset neutropenia.

Keywords

Gastric cancer, Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, DCF regimen, Progression-free survival.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the world's second most common cause of cancer-related death, and most patients are diagnosed with advanced gastric carcinoma and are no longer eligible for surgery [1]. These patients were most commonly treated with palliative systemic chemotherapy [2], but the relative toxicities of chemotherapy regimens remain a problem despite evidence of the advantage of chemotherapy. Specifically, patients may experience varying levels of toxicities during chemotherapy, and chemotherapy-induced neutropenia is one of the main dose-limiting toxicities associated with many cytotoxic drugs [3]. Specifically, this type of neutropenia has been favourably associated with survival in several types of cancer [4-6], including breast cancer [3], advanced non-small-cell lung cancer [5], and metastatic colorectal cancer [7]. These articles suggested that chemotherapy-induced neutropenia was closely related a better treatment response and improved survival. We herein describe a retrospective analysis of 110 consecutive patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving DCF as first-line chemotherapy. Our goal was to investigate the association between chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and treatment response or prognosis in patients with advanced gastric cancer. We hypothesized that chemotherapy-induced neutropenia (CIN) may serve as a surrogate marker of better clinical outcomes in advanced gastric cancer [8].

Materials and Methods

Patients

We searched the database at our hospital for records of advanced gastric cancer from January 2007 to December 2012. A total of 110 consecutive patients with histologically confirmed advanced gastric cancer who completed 2-6 cycles of DCF triplet chemotherapy (docetaxel-platinum-fluorouracil) at the PLA general hospital (Beijing, China) were ultimately identified and included. The inclusion criteria were defined as follows: age less than 75 years, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0 or 1, inoperable gastric cancer, the presence of histologically proven unresectable gastric cancer, sufficient bone marrow function (leukocyte count 4.0 × 109/L, neutrophil count 2.0 × 109/L, platelet count 100 × 109/L, haemoglobin 9.0 g/DL), normal liver and renal functions, no history of prior chemotherapy for advanced disease, and no history of chemotherapy before the commencement of DCF treatment [3]. The exclusion criteria included the following: accepted surgery, history of other cancers, essential data unavailable, or underwent other chemotherapy prior to the DCF regimen. The clinicopathological features and demographic characteristics of the patients and the results of the neutropenia tests were extracted from the medical records. The patients were followed up by telephone until May 2014 to obtain survival information. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital; all aspects of the study comply with the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethics Committee of Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital specifically ensured that data were analysed anonymously.

Treatment delivery

All patients underwent a chemotherapeutic protocol prescribed by the PLA general hospital consisting of 75 mg/m2 docetaxel (day 1), 75 mg/m2 cisplatin (day 1), and 750 mg/m2 fluorouracil (days 1-5) administered in 3-week intervals. Treatment was discontinued upon disease progression, severe toxicity or after completing 6 cycles of therapy. The prophylactic use of antibiotics or granulocyte colonystimulating factor (G-CSF) was not permitted, except in the event of grade 4 neutropenia or febrile neutropenia. In case of grade 3 neutropenia, the docetaxel or cisplatin dose was reduced by 20%. Treatment was delayed in all cases of grade 4 or febrile neutropenia until cytotoxic manifestations were resolved. The relative dose intensity (RDI) was determined by calculating the ratio of the actual dose intensity to the ideal value if all planned doses were given on schedule.

Response assessment

Each patient was physically examined using chest, abdominal and pelvic CT scans or echography after every two cycles of chemotherapy, and treatment efficacy was evaluated by comparing the baseline metastatic lesions. The response to chemotherapy was assessed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST 1.1 criteria). The diameter of measurable lesions should be longer than 10 mm, which was the detection limit for CT scans or echography [9]. Complete remission (CR) was defined as the complete disappearance of all target lesions. A decrease in the crosssectional area of all target lesions of at least 30% was defined as a partial response (PR). Progressive disease (PD) was defined as an increase of at least 20% in the tumour mass of metastatic nodes or at least one lesion or the appearance of a new lesion. Stable disease was defined as a decrease in lesion size of less than 30% or an increase of less than 20% [10-12].

Evaluation of neutropenia and supportive therapy

Routine blood samples were taken from all patients on the day before treatment and after approximately 4, 7 and 10 days of chemotherapy during each chemotherapy cycle. CIN was graded in accordance with the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE, version 3.0) as follows: CIN Grade 1 (between 1.5 × 109/L and 2.0 × 109/L), CIN Grade 2 (between 1.0 × 109/L and 1.5 × 109/L), CIN Grade 3 (between 0.5 × 109/L and 1.0 × 109/L), and CIN Grade 4 (<0.5 × 109/L). The worst grade of CIN was defined as the lowest recorded neutropenia count after six cycles of DCF chemotherapy for a given patient. To evaluate chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, CIN was classified into the following four categories: absent (grade 0), mild (grade 1~2), moderate (grade 3), and severe (grade 4). In our study, we further categorized the CIN according to the timing of neutropenia as follows: early-onset neutropenia was defined as the lowest grade neutropenia during cycle 1-3; lateonset neutropenia was defined as the worst grade of CIN during cycles 4-6, including the absence of neutropenia [9,13].

Statistical analysis

Overall survival (OS) was the primary study endpoint. The secondary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS) and the disease control rate (DCR). OS was defined as the interval from the onset of the DCF regimen to the date of death or loss follow-up. PFS was defined as the interval between the onset of chemotherapy and the date of progression or death due to any cause. DCR included patients in complete or partial radiographic remission and patients with stable disease. The survival curves of the four categories were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. The distribution of subject characteristics was assessed using the χ2 test, and the response rates were evaluated using Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The mean of continuous variables was determined using Student’s t-test. To evaluate the association between clinical pathological features and OS, univariate and multivariate cox proportional hazards modelling was applied. All statistical tests and P values were two-sided, and P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The demographics and clinical characteristics of 110 patients

A total of 110 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included in this retrospective analysis, including 90 (82%) males and 20 (18%) females, and the median age was 55 years (range: 20-75 years). In the entire population, 55 (50%) patients suffered from liver metastases, whereas 55 patients had no evidence of liver metastases. Although 57 (52%) patients harboured only 1-2 metastatic lesions, 53 (48%) patients exhibited 3 or more metastases. Among the 110 patients, 15 (13.6%) patients did not exhibit CIN (grade 0), 54 (49.1%) patients experienced mild CIN (grade 1-2), 22 (20.0%) patients had moderate CIN (grade 3), and 19 (17.3%) patients developed severe CIN (grade 4) during first-line chemotherapy. Early-onset CIN and late-onset CIN developed in 60% (66/110) and 40% (44/110) of patients. The demographics and clinical characteristics of these 110 patients, such as gender, age, BSA, and tumour differentiation, were categorized according the CIN, as shown in Tables 1 and 2. These characteristics did not significantly differ between the four neutropenia groups (P values <0.05 were considered significant). The relative dose intensity and cycles of first-line chemotherapy did not significantly differ between groups.

| Case N (%) | G0 (absent) | G1-2 (mild) | G3 (moderate) | G4 (severe) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 90 (82) | 13 | 45 | 14 | 18 | 0.062 |

| Female | 20 (18) | 2 | 9 | 8 | 1 | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| ≤ 60 | 31 (28) | 3 | 15 | 9 | 4 | 0.434 |

| >60 | 79 (72) | 12 | 39 | 13 | 15 | |

| RDI | ||||||

| Docetaxel | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.166 |

| Cisplatin | 0.89 | 0.9 | 0.92 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.257 |

| 5-FU | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.9 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.12 |

| Cycles of chemotherapy | ||||||

| (mean ± SD ) | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 0.106 |

| Differentiation | ||||||

| Poorly | 54 (49) | 10 | 22 | 10 | 12 | 0.173 |

| Moderately-well | 56 (51) | 5 | 32 | 12 | 7 | |

| BSA | ||||||

| ≤ 1.6 m2 | 28 (25) | 3 | 13 | 7 | 5 | 0.857 |

| >1.6 m2 | 82 (75) | 12 | 41 | 15 | 14 | |

| ECOGPS | ||||||

| 0-1 | 50 (45) | 4 | 27 | 11 | 8 | 0.415 |

| 2-3 | 60 (55) | 11 | 27 | 11 | 11 | |

| Her-2 | ||||||

| Negative | 53 (48) | 3 | 29 | 9 | 12 | 0.55 |

| Positive | 57 (52) | 12 | 25 | 13 | 7 | |

| Liver metastasis | ||||||

| No | 55 (50) | 5 | 28 | 12 | 10 | 0.578 |

| Yes | 55 (50) | 10 | 26 | 10 | 9 | |

| Metastasis site | ||||||

| 1-2 | 57 (52) | 4 | 28 | 10 | 11 | 0.277 |

| 3 or more | 53 (48) | 11 | 26 | 12 | 8 | |

| Tumour location | ||||||

| Upper | 46 (42) | 7 | 22 | 7 | 10 | 0.707 |

| Middle | 25 (23) | 2 | 15 | 5 | 3 | |

| Lower | 39 (35) | 6 | 17 | 10 | 6 | |

Table 1. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics in all patients and in subgroups stratified according to the worst grade of neutropenia during six cycles.

| Case | Early-onset neutropenia | Late-onset neutropenia | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N=66 (60%) | N=44 (40%) | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 90 (82) | 52 | 38 | 0.052 |

| Female | 20 (18) | 14 | 6 | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤ 60 | 31 (28) | 18 | 13 | 0.224 |

| >60 | 79 (72) | 48 | 31 | |

| RDI | ||||

| docetaxel | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.106 |

| Cisplatin | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.147 |

| 5-FU | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.09 |

| Cycles of chemotherapy | ||||

| (mean ± SD ) | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | 0.125 |

| Differentiation | ||||

| poorly | 54 (49) | 38 | 16 | 0.273 |

| Moderately-well | 56 (51) | 28 | 28 | |

| BSA | ||||

| ≤ 1.6 m2 | 28 (25) | 12 | 16 | 0.657 |

| >1.6 m2 | 82 (75) | 54 | 28 | |

| ECOGPS | ||||

| 0-1 | 50 (45) | 40 | 10 | 0.515 |

| 2-3 | 60 (55) | 26 | 34 | |

| Her-2 | ||||

| Negative | 53 (48) | 31 | 22 | 0.411 |

| Positive | 57 (52) | 35 | 22 | |

| Liver metastasis | ||||

| No | 55 (50) | 35 | 20 | 0.338 |

| Yes | 55 (50) | 31 | 24 | |

| Metastasis site | ||||

| 1-2 | 57 (52) | 27 | 30 | 0.207 |

| 3 or more | 53 (48) | 39 | 14 | |

| Tumour location | ||||

| Upper | 46(42) | 21 | 25 | 0.517 |

| Middle | 25(23) | 13 | 12 | |

| Lower | 39(35) | 32 | 7 | |

Table 2. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics in all patients and in subgroups stratified according to the timing of neutropenia during six cycles.

Relationship between chemotherapy-induced neutropenia (CIN) and survival

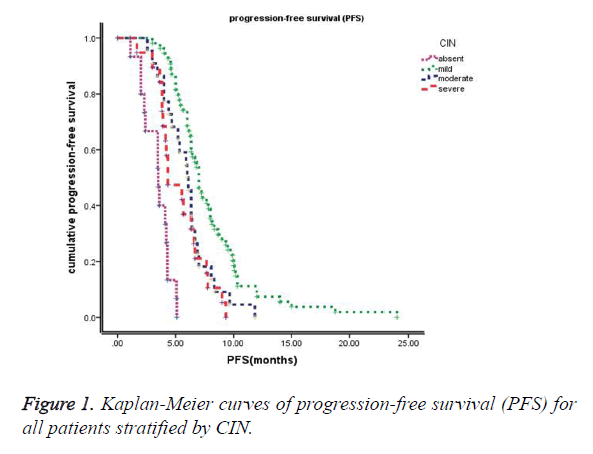

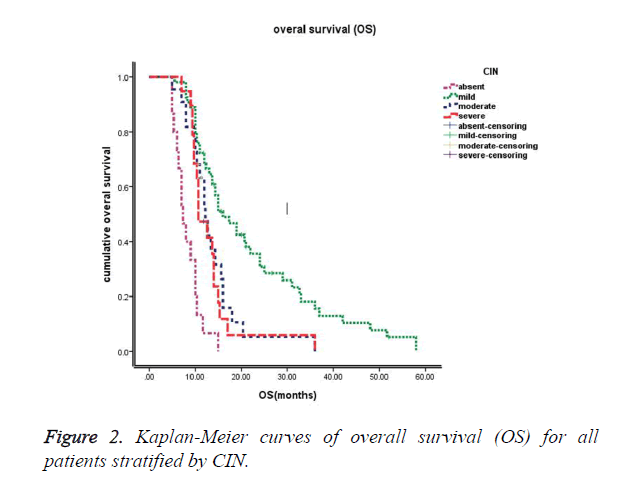

The median follow-up time at the time of this study was 30 months. The median progression-free survival (PFS) of these 110 patients was 6.0 months (95% CI: 5.5~6.6 months), and the median overall survival (OS) of these 110 patients was 12.7 months (95% CI: 11.2~14.2 months). Kaplan-Meier survival curves based on chemotherapy-induced neutropenia (CIN) are shown in Figure 1 (PFS) and Figure 2 (OS). The median progression-free survival times for absent (grade 0), mild (grade 1-2), moderate (grade 3) and severe (grade 4) CIN were 3.5 months, 7.0 months, 6.0 months, and 4.3 months, respectively. The median overall survival times were 7.3 months, 16.0 months, 12.2 months, and 10.7 months for absent (grade 0), mild (grade 1-2), moderate (grade 3) and severe (grade 4) CIN, respectively. Furthermore, patients exhibiting early-onset neutropenia experienced significantly better clinical outcomes (PFS and OS) than patients exhibiting late-onset neutropenia, with median PFS times of 6.8 months and 5.6 months, respectively (P<0.05) and median OS times of 14.9 months and 12.1 months, respectively (P<0.05). The overall survival rates of the 110 patients were 83%, 39%, and 16% at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years, respectively.

Univariate and multivariate analysis focused on neutropenia and other clinicopathological parameters of advanced gastric cancer (Tables 3 and 4), including gender (male vs. female), age (≤ 60 vs. >60), differentiation (poorly vs. moderately-well), BSA (body surface area) (≤ 1.6 m2 vs. >1.6 m2), performance status (0-1 vs. 2-3), presence of a liver metastasis (yes vs. no), her-2 amplification (positive vs. negative), metastasis site (1-2 vs. 3 or more), and tumour location (upper vs. middle vs. lower). Table 3 shows that the timing and degree of CIN, differentiation, PS (performance status), presence of a liver metastasis, her-2 amplification, and metastasis site significantly correlated with a better PFS and OS in the univariate analysis. Table 4 shows that the timing and degree of CIN, performance status, presence of a liver metastasis, and her-2 amplification served as independent prognosticators of improved PFS, whereas the timing and degree of CIN and presence of a liver metastasis independently predicted better OS in a multivariate analysis. The result of a Cox regression analysis for the association between CIN and survival is shown in Table 4.

| Case | PFS (m) | OS (m) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Median | χ2 | P value | Median | χ2 | P value | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 90 (82) | 6 | 0.001 | 0.979 | 12.7 | 0.004 | 0.948 |

| Female | 20 (18) | 6.2 | 12.6 | ||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| ≤ 60 | 31 (28) | 6.3 | 0.012 | 0.911 | 13.7 | 0.265 | 0.607 |

| >60 | 79 (72) | 6 | 12.2 | ||||

| Differentiation | |||||||

| Poorly | 54 (49) | 5.1 | 8.403 | 0.004<0.05 | 10.3 | 4.845 | 0.028<0.05 |

| Moderately-well | 56 (51) | 6.4 | 15 | ||||

| BSA | |||||||

| ≤ 1.6 m2 | 28 (25) | 6.2 | 0.029 | 0.865 | 13.3 | 0.394 | 0.53 |

| >1.6 m2 | 82 (75) | 6 | 12.3 | ||||

| ECOGPS | |||||||

| 0-1 | 50 (45) | 7.2 | 17.065 | 0.000<0.05 | 15 | 4.261 | 0.039<0.05 |

| 2-3 | 60 (55) | 4.7 | 10.7 | ||||

| Her-2 | |||||||

| Negative | 53 (48) | 7 | 20.994 | 0.000<0.05 | 15 | 5.106 | 0.024<0.05 |

| Positive | 57 (52) | 5.3 | 11 | ||||

| Liver metastasis | |||||||

| No | 55 (50) | 6.6 | 6.886 | 0.009<0.05 | 15 | 16.614 | 0.00<0.05 |

| yes | 55 (50) | 5.4 | 10.3 | ||||

| Metastasis site | |||||||

| 1-2 | 57 (52) | 6.6 | 7.809 | 0.005<0.05 | 15 | 12.544 | 0.00<0.05 |

| 3 or more | 53 (48) | 5.4 | 10.3 | ||||

| Tumour location | |||||||

| Upper | 46(42) | 6 | 0.543 | 0.762 | 12.2 | 1.578 | 0.454 |

| Middle | 25(23) | 6 | 14.3 | ||||

| Lower | 39(35) | 6.3 | 12 | ||||

| Timing of CIN | |||||||

| Early-onset | 66(66) | 6.8 | 9.804 | 0.010<0.05 | 14.9 | 3.375 | 0.01<0.05 |

| Late-onset | 44(44) | 5.6 | 12.1 | ||||

| Degree of CIN | |||||||

| G0 | 15 (14) | 3.5 | 72.144 | 0.00<0.05 | 7.3 | 50.123 | 0.00<0.05 |

| G1~2 | 54 (49) | 7 | 16 | ||||

| G3 | 22 (20) | 6 | 12.2 | ||||

| G4 | 19 (17) | 4.3 | 10.7 | ||||

| G1~2 vs. G0 | - | - | 69.669 | 0.00 | - | 40.017 | 0.00 |

| G3 vs. G0 | - | - | 20.897 | 0.00 | - | 14.406 | 0.00 |

| G4 vs. G0 | - | - | 10.894 | 0.001 | - | 10.886 | 0.001 |

| G1~2 vs. G3 | - | - | 6.961 | 0.008 | - | 7.785 | 0.005 |

| G1~2 vs. G4 | - | - | 12.755 | 0.00 | - | 9.158 | 0.002 |

| G3 vs. G4 | - | - | 0.839 | 0.36 | - | 0.392 | 0.531 |

Table 3. Univariate analysis for the association between chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and survival.

| PFS(m) | OS(m) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wald | P | HR | 95% CI | Wald | P | HR | 95% CI | |

| Differentiation | ||||||||

| Poorly | - | 0.161 | - | - | - | 0.194 | - | - |

| Moderately-well | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ECOG PS | ||||||||

| 0-1 | 8.111 | 0.004 | 0.527 | 0.339-0.819 | 0.35 | |||

| 2-3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Her-2 | ||||||||

| Negative | 6.836 | 0.009 | 0.522 | 0.320-0.850 | 0.464 | |||

| Positive | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Liver metastasis | ||||||||

| No | 5.19 | 0.023 | 0.629 | 0.423-0.937 | 16.705 | 0.000 | 0.389 | 0.247-0.611 |

| Yes | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Metastasis site | ||||||||

| 1-2 | 0.743 | 0.807 | ||||||

| 3 or more | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Timing of CIN | ||||||||

| Early-onset | 4.233 | 0.035 | 0.713 | 0.532-0.897 | 10.151 | 0.040 | 0.688 | 0.499-0.874 |

| Late-onset | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Degree of CIN | 50.176 | 0.00 | - | - | 38.917 | 0.000 | - | - |

| G1~2 | 11.065 | 0.001 | 0.268 | 0.123-0.582 | 7.876 | 0.005 | 0.362 | 0.178-0.736 |

| G3 | 17.885 | 0.000 | 0.595 | 0.368-0.720 | 11.815 | 0.001 | 0.765 | 0.448-0.997 |

| G4 | 1.126 | 0.009 | 0.712 | 0.380-1.333 | 0.125 | 0.023 | 0.791 | 0.470-1.688 |

Table 4. Multivariate Cox models for the association between chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and survival.

For progression-free survival (PFS), the HR for mild CIN (grade 1-2) compared with absent CIN (grade 0) was 0.268 (95% CI: 0.123-0.582, P<0.001), which represented a 73.2% lower risk of disease progression; similarly, the HR for moderate CIN (grade 3) compared with absent CIN (grade 0) was 0.595 (95% CI: 0.368-0.720, P=0.00), which corresponded to a 40.5% lower risk of disease progression; the HR for severe CIN (grade 4) compared with absent CIN (grade 0) was 0.712 (95% CI: 0.380-1.333, P=0.001), which indicated a 28.8% lower risk of disease progression. The hazard ratio for disease progression was significantly lower for early-onset CIN than late-onset CIN (HR=0.713, [95% CI=0.532-0.897], P=0.035).

For overall survival (OS), the HR for mild CIN (grade 1-2) compared with absent CIN (grade 0) was 0.362 (95% CI: 0.178-0.736, P<0.001), which represented a 63.8% lower risk of death; similarly, the HR for moderate CIN (grade 3) was 0.765 (95% CI: 0.448-0.997, P=0.002), which corresponded to a 23.5% lower risk of death; the HR for severe CIN (grade 4) was 0.791 (95% CI: 0.470-1.688, P=0.005), which indicated a 20.9% lower risk of death. The hazard ratio for death was significantly lower for early-onset CIN than late-onset CIN (HR=0.688, [95% CI=0.499-0.874], p=0.040).

Response to chemotherapy

The overall response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) is summarized in Table 5. The clinical effects of 6 cycles of DCF chemotherapy in 110 patients were as follows: no patients achieved CR, 43 (39%) patients exhibited PR, 29 (26%) patients attained SD, and 38 (35%) patients experienced PD. The total ORR and DCR among these 110 patients were 39% and 65%, respectively. In a subgroup analysis, the overall response rates for absent (grade 0), mild (grade 1-2), moderate (grade 3) and severe (grade 4) CIN were 13.3%, 53.7%, 45.5%, and 10.5%, respectively, and the disease control rates were 33.3%, 75.9%, 68.2%, and 57.9%, respectively. Overall, chemotherapy-induced neutropenia (CIN) also predicted improved disease control in advanced gastric cancer.

| Degree of CIN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0 | G1~2 | G3 | G4 | P value | |

| ORR (%) | 13.3 | 53.7 | 45.5 | 10.5 | 0.001 |

| (2/15) | (29/54) | (10/22) | (2/19) | ||

| DCR (%) | 33.3 | 75.9 | 68.2 | 57.9 | 0.018 |

| (5/15) | (41/54) | (15/22) | (11/19) | ||

Table 5. Response rates and disease control rates.

Discussion

In conclusion, a subgroup analysis indicated that mild, moderate and severe CIN tended to be associated with improved prognosis compared with absent CIN. Additionally, patients who experienced mild (grade 1-2) CIN had a more favourable prognosis than patients with either moderate (grade 3) or severe (grade 4) CIN. Nevertheless, both moderate and severe CIN favourably impacted patients to almost the same degree. Furthermore, the timing of CIN was associated with PFS and OS as follows: the early-onset neutropenia group demonstrated significantly better clinical outcomes than the late-onset neutropenia group. Based on this analysis, univariate and multivariate analyses confirmed that CIN during first-line chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer was associated with better survival.

Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia is well known to be one of the most important dose-limiting toxicities of cytotoxic drugs that often necessitates a reduction in the initial dosage [12]. In this study, we investigated the association between chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and prognosis in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Monitoring neutropenia in patients who receive chemotherapy may contribute to improved drug efficacy and survival [5]. We herein described a retrospective analysis of 110 consecutive patients treated with DCF as first-line chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. We found that early-onset CIN and the degree of CIN (any grade) was associated with improved prognosis. Specifically, the mild, moderate, severe CIN all favourably impacted patient outcomes (PFS: HR=0.268 for mild CIN, HR= 0.595 for moderate CIN, and HR=0.712 for severe CIN; OS: HR=0.362 for mild CIN, HR=0.765 for moderate CIN, and HR=0.791 for severe CIN). The hazard ratios for disease progression and death were significantly lower for early-onset CIN than lateonset CIN (HR=0.713, [95% CI=0.532-0.897], p=0.035 and HR=0.688, [95% CI=0.499-0.874], p=0.040, respectively). To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to examine the prognostic role of the timing and degree of CIN in advanced gastric cancer patients receiving the DCF regimen.

Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia is reportedly favourably associated with survival in a variety of solid tumours, including non-small cell lung, colorectal, gastric, breast, cervical and ovarian cancer [5,13-22]. Since the late 1990s, many studies have reported better clinical outcomes for patients with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. Di-Maio et al. demonstrated a positive correlation between chemotherapyinduced neutropenia and survival in by analysing pooled data from three randomized trials of 1265 patients with non-small cell lung cancer [5]. They concluded that both mild (grade 1-2) and severe (grade 3-4) neutropenia improved survival and chemotherapy efficacy compared with absent (grade 0) neutropenia. A similar result was reported for mCRC (metastatic colorectal cancer). Specifically, Shitara et al. retrospectively analysed 153 patients with advanced colorectal cancer receiving FOLFOX with or without bevacizumab as a first-line chemotherapy and found that any degree of CIN was associated with a favourable outcome [13]. Rambach et al. extended this study to a larger population receiving different chemotherapy regimens and found that the favourable prognostic role of neutropenia during treatment for mCRC was a common phenomenon that may not depend on the type of chemotherapy [23]. Jang et al. retrospectively analysed a total of 123 patients with stage IV NSCLC receiving at least two cycles of first-line doublet chemotherapy (gemcitabine plus platinum) and found that early-onset CIN may be a surrogate marker for improved disease control and favourable prognosis in patients with metastatic NSCLC [9]. These findings prompted us to rigorously quantify the prognostic value of the degree and timing of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia with respect to survival outcomes and treatment response in advanced gastric cancer patients undergoing first-line chemotherapy with DCF.

In our study, the relative dose intensity did not significantly differ between patients with and without neutropenia. Therefore, the improved response to chemotherapy and prognosis of patients with CIN were not associated with a reduction in dose. Because patients surviving longer are more likely receive additional cycles of chemotherapy, the number of chemotherapy cycles directly correlated with the incidence of CIN. To avoid this bias, treatment was discontinued upon disease progression, severe toxicity or after six cycles of chemotherapy.

The cause of this inter-patient variation is unclear, but it may be due to gene polymorphisms related to drug elimination or metabolism. The pharmacokinetics of cytotoxic drugs is equal for tumour cells and healthy cells; therefore, the neutrophil count can serve as a surrogate marker of cytotoxic agents and chemotherapy sensitivity. The sensitivity of tumour cells reflects a genetic predisposition, which is the same for all cells [24]. Because certain subpopulations of cancer cells have inherited normal stem cell properties and genetic predispositions, including the capacity for self-renewal and the ability to differentiate and metastasize, cancer stem cell suppression correlates with normal stem cell suppression [25]. Therefore, neutropenia represents the adequate exposure of tumour cells to cytotoxic drugs [26]. In other words, the absence of neutropenia during treatment might be associated with under-dosing [17]. We usually determine the dose of cytotoxic agents based on the body surface area (BSA). However, several prospective randomized studies [27,28] have suggested that the BSA-based dosing system may be not appropriate in many cases, and the optimal dose of cytotoxic drugs is not necessarily determined by the use of BSA-dosing guidelines. In fact, the dose optimization and calculation of a tailored regimen taken into account not only the body surface area but also bodyweight, sex, and age. Nearly two decades ago, Gurney [27] described the limitations of BSA-based dosing, which cannot account for the complex processes of drug elimination and metabolism. Thus, up to 30% of patients receive treatment with unrecognized under-dosing, and these patients at risk of reduced efficacy and ultimately, poor survival.

Neutrophils may promote the occurrence and development of a tumour via the following mechanism: accumulating evidence has shown that neutrophils contribute to tumour angiogenesis, and an increase in the neutrophil population induces resistance to anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy [29,30]. Recent studies suggest that neutrophils play an important role in the induction of the angiogenic switch in cancer, as illustrated in a transgenic mouse model of pancreatic h-cell carcinogenesis [31]. Consequently, neutrophils may be a surrogate indicator for tumour cells acquiring resistance to chemotherapy agents. Significant strengths of this study include that the patients were treated at a single institution by a limited number of physicians and follow-up was relatively long and complete. Unlike a typical exposure of interest, such as a chemotherapy regimen, chemotherapy-induced neutropenia is less likely to be influenced by the investigator’s intention. Quality control was overseen by the National Cancer Institute and its data safety monitoring board. However, this study was also subject to several methodological limitations. First, this study is retrospective and examined a small sample, and patients were not randomly assigned to a chemotherapy procedure, which can lead to patient selection bias. Moreover, OS, which was the primary endpoint, may have been confounded by different subsequent chemotherapy regimens, radiotherapy treatment, etc.

In conclusion, our rigorous statistical study demonstrated that patients with early-onset CIN and any grade of CIN reaped greater survival benefits from the treatment than patients with late-onset CIN or patients who did not develop CIN. Specifically, the absence of neutropenia may be a sign of an inadequate chemotherapy dose. Mild neutropenia resulted in the best treatment efficacy and survival, but the treatment efficacy and survival benefit did not significantly differ between severe and moderate neutropenia. Our study suggests that chemotherapy-induced neutropenia can be used to individualize a pharmacologically active dose, and the use of CIN as a guide to tailor dosages warrants further attention. Prospective randomized trials are required to evaluate the ability of dosing adjustments based on neutropenia to improve chemotherapy efficacy and survival. An additional welldefined prospective trial to explore safe intra-patient dose escalation with the intent of achieving neutropenia is warranted.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all the support from the staff at the department of Oncology 2, Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010; 127: 2893-2917.

- Proserpio I, Rausei S, Barzaghi S, Frattini F, Galli F. Multimodal treatment of gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2014; 6: 55-58.

- Han Y, Yu Z, Wen S, Zhang B, Cao X. Prognostic value of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia in early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012; 131: 483-490.

- Martin M, Villar A, Sole-Calvo A, Gonzalez R, Massuti B, Lizon J, Camps C, Carrato A, Casado A, Candel MT, Albanell J, Aranda J, Munarriz B, Campbell J, Diaz-Rubio E. Doxorubicin in combination with fluorouracil and cyclophosphamide (i.v. FAC regimen, day 1, 21) versus methotrexate in combination with fluorouracil and cyclophosphamide (i.v. CMF regimen, day 1, 21) as adjuvant chemotherapy for operable breast cancer: a study by the GEICAM group. Ann Oncol 2003; 14: 833-842.

- Di Maio M, Gridelli C, Gallo C, Shepherd F, Piantedosi FV, Cigolari S, Manzione L, Illiano A, Barbera S, Robbiati SF, Frontini L, Piazza E, Ianniello GP, Veltri E, Castiglione F, Rosetti F, Gebbia V, Seymour L, Chiodini P, Perrone F. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and treatment efficacy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a pooled analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet Oncol 2005; 6: 669-677.

- Yamanaka T, Matsumoto S, Teramukai S, Ishiwata R, Nagai Y, Fukushima M. Predictive value of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia for the efficacy of oral fluoropyrimidine S-1 in advanced gastric carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2007; 97: 37-42.

- Shitara K, Matsuo K, Yokota T, Takahari D, Shibata T, Ura T, Inaba Y, Yamaura H, Sato Y, Najima M, Muro K. Prognostic factors for metastatic colorectal cancer patients undergoing irinotecan-based second-line chemotherapy. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2011; 4: 168-172.

- Tewari KS, Java JJ, Gatcliffe TA, Bookman MA, Monk BJ. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia as a biomarker of survival in advanced ovarian carcinoma: an exploratory study of the gynecologic oncology group. Gynecol Oncol 2014; 133: 439-445.

- Jang SH, Kim SY, Kim JH, Park S, Hwang YI, Kim DG, Jung KS. Timing of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia is a prognostic factor in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a retrospective analysis in gemcitabine-plus-platinum-treated patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2013; 139: 409-417.

- Capitain O, Asevoaia A, Boisdron-Celle M, Poirier AL, Morel A, Gamelin E. Individual fluorouracil dose adjustment in FOLFOX based on pharmacokinetic follow-up compared with conventional body-area-surface dosing: a phase II, proof-of-concept study. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2012; 11: 263-267.

- Miyoshi N, Yano M, Takachi K, Kishi K, Noura S, Eguchi H, Yamada T, Miyashiro I, Ohue M, Ohigashi H, Sasaki Y, Ishikawa O, Doki Y, Imaoka S. Myelotoxicity of preoperative chemoradiotherapy is a significant determinant of poor prognosis in patients with T4 esophageal cancer. J Surg Oncol 2009; 99: 302-306.

- Crawford J, Dale DC, Lyman GH. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: risks, consequences, and new directions for its management. Cancer 2004; 100: 228-237.

- Shitara K, Matsuo K, Takahari D, Yokota T, Inaba Y, Yamaura H, Sato Y, Najima M, Ura T, Muro K. Neutropaenia as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy with first-line FOLFOX. Eur J Cancer 2009; 45: 1757-1763.

- Shitara K, Matsuo K, Oze I, Mizota A, Kondo C. Meta-analysis of neutropenia or leukopenia as a prognostic factor in patients with malignant disease undergoing chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2011; 68: 301-307.

- Shitara K, Matsuo K, Takahari D, Yokota T, Shibata T, Ura T, Ito S, Sawaki A, Tajika M, Kawai H, Muro K. Neutropenia as a prognostic factor in advanced gastric cancer patients undergoing second-line chemotherapy with weekly paclitaxel. Ann Oncol 2010; 21: 2403-2409.

- Koutras AK, Fountzilas G, Dafni U, Dimopoulos MA, Pectasides D, Klouvas G, Papakostas P, Kosmidis P, Samantas E, Gogas H, Briasoulis E, Vourli G, Petsas T, Xiros N, Kalofonos HP. Myelotoxicity as a prognostic factor in patients with advanced breast cancer treated with chemotherapy: a pooled analysis of two randomised trials conducted by the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group. Anticancer Res 2008; 28: 2913-2920.

- Kim YH, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, Kang SB. Prognostic significance of neutropenia during adjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy in early cervical cancer. J Gynecol Oncol 2009; 20: 146-150.

- Rocconi RP, Matthews KS, Kemper MK, Hoskins KE, Barnes MN. Chemotherapy-related myelosuppression as a marker of survival in epithelial ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 2008; 108: 336-341.

- Kim JJ, Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, Kim YM. Is chemotherapy-induced neutropenia a prognostic factor in patients with ovarian cancer? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010; 89: 623-628.

- Carus A, Gurney H, Gebski V, Harnett P, Hui R, Kefford R, Wilcken N, Ladekarl M, von der Maase H, Donskov F. Impact of baseline and nadir neutrophil index in non-small cell lung cancer and ovarian cancer patients: Assessment of chemotherapy for resolution of unfavourable neutrophilia. J Transl Med 2013; 11: 189.

- Lee CK, Gurney H, Brown C, Sorio R, Donadello N, Tulunay G, Meier W, Bacon M, Maenpaa J, Petru E, Reed N, Gebski V, Pujade-Lauraine E, Lord S, Simes RJ, Friedlander M. Carboplatin-paclitaxel-induced leukopenia and neuropathy predict progression-free survival in recurrent ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 2011; 105: 360-365.

- Banerjee S, Rustin G, Paul J, Williams C, Pledge S, Gabra H, Skailes G, Lamont A, Hindley A, Goss G, Gilby E, Hogg M, Harper P, Kipps E, Lewsley LA, Hall M, Vasey P, Kaye SB. A multicenter, randomized trial of flat dosing versus intrapatient dose escalation of single-agent carboplatin as first-line chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer: an SGCTG (SCOTROC 4) and ANZGOG study on behalf of GCIG. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 679-687.

- Rambach L, Bertaut A, Vincent J, Lorgis V, Ladoire S, Ghiringhelli F. Prognostic value of chemotherapy-induced hematological toxicity in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 1565-1573.

- Fisher B, Anderson S, Wickerham DL, DeCillis A, Dimitrov N, Mamounas E, Wolmark N, Pugh R, Atkins JN, Meyers FJ, Abramson N, Wolter J, Bornstein RS, Levy L, Romond EH, Caggiano V, Grimaldi M, Jochimsen P, Deckers P. Increased intensification and total dose of cyclophosphamide in a doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide regimen for the treatment of primary breast cancer: findings from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project B-22. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 1858-1869.

- Wood WC, Budman DR, Korzun AH, Cooper MR, Younger J. Dose and dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II, node-positive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 1253-1259.

- Kvinnsland S. The leucocyte nadir, a predictor of chemotherapy efficacy? Br J Cancer 1999; 80: 1681.

- Gurney H. How to calculate the dose of chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 2002; 86: 1297-1302.

- Newell DR. Getting the right dose in cancer chemotherapy--time to stop using surface area? Br J Cancer 2002; 86: 1207-1208.

- Shojaei F, Wu X, Qu X, Kowanetz M, Yu L. G-CSF-initiated myeloid cell mobilization and angiogenesis mediate tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF therapy in mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009; 106: 6742-6747.

- Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Fleming GF, Monk BJ. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 2473-2483.

- Giordano G, Febbraro A, Venditti M, Campidoglio S, Olivieri N. Targeting angiogenesis and tumor microenvironment in metastatic colorectal cancer: role of aflibercept. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2014; 2014: 526178.