Research Paper - Journal of Intensive and Critical Care Nursing (2023) Volume 6, Issue 2

′′I want to continue living for at least a few more years′′− health in relation to cardiac surgery among fragile patients.

Carina Hjelm1*, Jenny Eskilsson2, Susanna Agren1,21Department of Health, Medicine and Care, Nursing and Reproductive Health, Linköping University, Sweden.

2Department of Thoracic and Vascular Surgery, University Hospital, Linköping, Sweden.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Carina Hjelm

Department of Health, Medicine and Care

Nursing and Reproductive Health

Linköping University, Sweden.

E-mail: carina.hjelm@liu.se

Received: 04-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. AAICCN-23-88762; Editor assigned: 06-Feb-2023, PreQC No. AAICCN-23-88762(PQ); Reviewed: 20-Feb-2023, QC No. AAICCN-23-88762; Revised: 23-Feb-2023, Manuscript No. AAICCN-23-88762(R); Published: 14-Mar-2023, DOI:10.35841/aaiccn-6.2.136

Citation: Hjelm C, Eskilsson J, Agren S. "I want to continue living for at least a few more years"– health in relation to cardiac surgery among fragile patients. J Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2023;6(2):136

Abstract

Background: Increased knowledge of how fragile patients undergoing heart surgery experience their health can provide opportunities to improve nursing of these patients. The intensive care nurse's adequate knowledge of the patient's life situation becomes an important prerequisite for providing person-centred care. Objective: To explore how fragile patients experience health, worry and anxiety in connection with heart surgery. Method: Qualitative interview study with a semi-structured interview guide. Narrative analysis method with an inductive approach was applied to empirical data from four participants. Findings: The analysis resulted in three themes: The Importance of Heart Surgery, The importance of Relationship`s and Shaping Life Events. These themes reflect the experience of heart surgery in the context of each patient’s life situation. Conclusion: Cardiac surgery is an opportunity to regain physical health and improve survival. Worry and anxiety were associated with the patient’s life situation and the patient's ability to handle it, and was unlikely to be related to the heart surgery itself. The fragile patient's relationships facilitated rehabilitation after cardiac surgery and had a strengthening effect on recovery.

Keywords

Heart Surgery, Health related Quality of Life, Patient-Centred Care, Frailty.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the largest common disease in Sweden, although incidence and mortality rate are steadily decreasing [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 17.9 million people die annually as a result of cardiovascular disease, representing 31 percent of all deaths globally. An increase in the number of deaths is estimated at 23 million by 2030. Two-thirds of deaths are of people over the age of 70 years (World Health Organization 2020). There are a number of known risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease such as overweight, smoking, high blood pressure, heredity, physical inactivity as well as advanced age [2].

A third of the population at age 65 years is believed to have calcified blood vessels, also known as arteriosclerosis [2]. The surgical outcome is affected by, among other things, how pronounced the patient's heart disease was before the operation and whether emergency surgery was carried out versus planned surgery [3].

In coronary artery disease, treatment with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) can have a major effect on survival according to national guidelines for cardiac care. There is a connection between cardiovascular disease and mental suffering, although the epidemiology has not yet been mapped. Studies indicate the importance of psychological factors in somatic disease.

Diseases of the heart and their consequences require many healthcare resources. Elderly patients have largely been shown to be a challenging category of patients due to their higher prevalence of other diseases, such as diabetes, cerebrovascular disease, and kidney failure, in addition to their heart disease.

The combined effect of emotional stress and heart failure is a risk factor for further worsening of heart failure [4].

Heart surgery is a major event in the patient's life, and the presence of both fear and worry have been identified in this patient group [5].

To forecast outcomes after surgery and intensive care, frailty should be taken into account when predicting outcomes after surgery and intensive care. Increasing frailty increases the degree of morbidity postoperatively, but it has also been shown that fragile individuals can increase their health-related quality of life despite their fragility [6]. There are several instruments for measuring fragility [7]. The Clinical frailty scale [8] is one of the accepted instruments.

Studies have highlighted that stress, depression, and anxiety are underdiagnosed in patients with heart disease. For the sufferer, this means a psychosocial burden [4]. Recent evidence indicates there is a relationship between preoperative depression and postoperative morbidity and mortality in elderly patients [5]. Preoperative frailty is a predisposing factor that risks exposing the patient to negative health consequences due to the stress of a heart operation [9]. The aim of this study was therefore to explore how fragile patients experience health, worry and anxiety in connection with heart surgery.

Methods

An empirical qualitative interview study with an inductive approach was conducted [10]. The theoretical basis of the study is narrative theory, and life story research. Narrative theory aims to increase understanding through new perspectives and by analysing the linguistic form of a story. The theory is about systematically interpreting individuals' descriptions of themselves to understand themselves and their actions in a more conscious way [11].

Data collection

To create agreement between the sample and the purpose of the study, a strategic selection was carried out [10]. Inclusion criteria: adult patients accepted for open heart surgery and use of a heart-lung machine. Participation in the study was voluntary, and participants had frailty level ≥ 5 according to the Clinical Frailty Scale.

Exclusion criteria: emergency surgery within 24 hours, individuals who could not speak or read the Swedish language, mental illness or other serious illness and cognitive impairment. Impairment, and patients who needed support to cope in everyday life. Dropouts: all patients from the selection group who met all criteria were invited to join this study, and all of them accepted. There was no dropout of participants.

Data collection was conducted with semi-structured individual interviews [12]. The interview questions were based on an interview guide and consisted of five open-ended questions (Appendix 1). The project was approved by the Ethical Review Authority in Sweden (reference number 2021– 04991).

The clinical frailty scale (CFS) is validated for the elderly (>65 years) and has proven to be a reliable measure of expected survival in combination with how the individual handles different medical and surgical treatments [13]. The scale is assessed as a user- friendly instrument and is based on normal activity level, mobility and how the individual can independently perform physical and cognitive activities [13]. Fragility scores range from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill). Mild frailty is rated as 5 points on the CFS.

Procedure

Patients who met the selection criteria received an information letter then received an enrollment call before the heart surgery with a request to participate in the current research project.

During the enrollment call for heart surgery, a fragility assessment was carried out according to the assessment instrument: the CFS [13]. All patients who were assessed as frail were asked to participate in the present study. These patients were contacted by the author who later conducted the interview, which was undertaken by phone about 3 months after surgery when the request for participation was still current. The survey group was equally divided regarding gender, and age ranged between 63 and 81 years, with mean 73 years. Number of days at the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery was one to two days and number of days in hospital varied between 10 to 17 days, on average 13 days. The participants themselves determined the time and place of the interview, which resulted in all interviews being conducted at participants' homes. All interviews were conducted with one author present (JE). The interviews were recorded with a dictaphone. The interviews were conducted during March and April 2022. The duration of the interviews was between 29 and 66 minutes, with mean 52 minutes.

Analysis

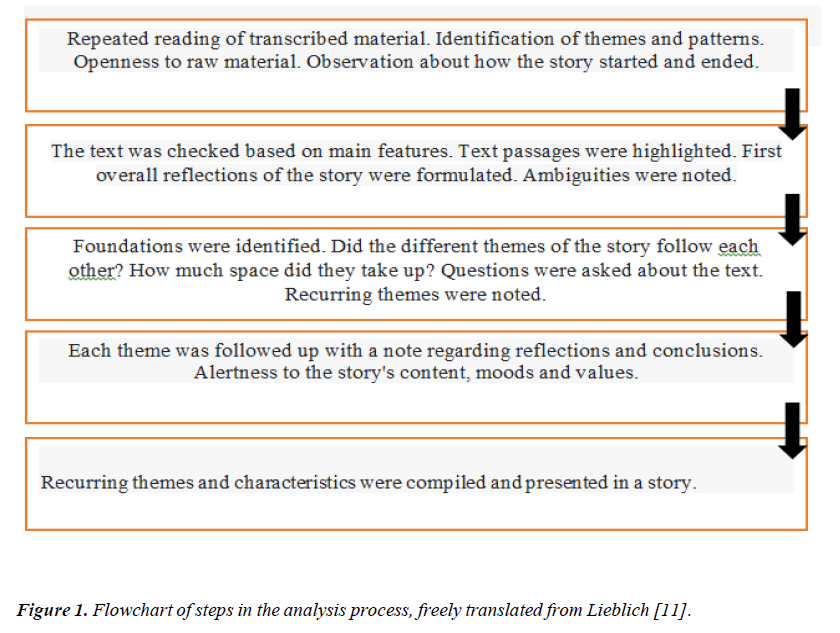

Once the material was transcribed, the analysis began with text from one interview at a time, in accordance with Lieblich [11]. Transcribed text in total’corresponded to about 4500 words per interview. Each individual interview had varied content that corresponded to the study aim. The initial processing of the text and repeated review were carried out independently so as not to affect each researcher’s assessments. Following this, the joint analysis process commenced in accord with Lieblich [11] flowchart (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flowchart of steps in the analysis process, freely translated from Lieblich [11].

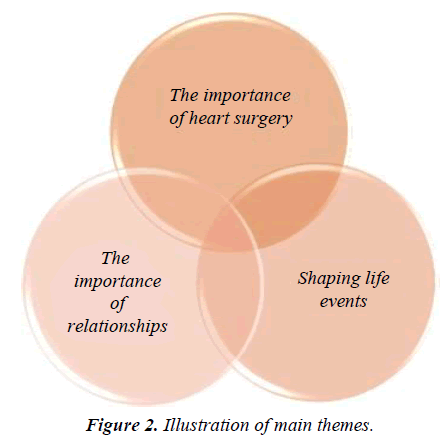

Final themes then culminated in stories being noted by the authors (Figure 2).

Findings

The findings are presented in a narrative story including three main themes (Figure 2): The importance of heart surgery, The importance of relationship`s and Shaping life events.

The importance of heart surgery is aimed at what the participants have highlighted in their stories about what heart surgery has meant for their health, worry and anxiety. Under the heading the importance of relationships, there are participants' reflections on their relationships. It also related to the feelings and causes of feelings that can arise between people. Shaping life events refers to crucial events that occurred earlier in life and thus shaped the patient’s identity, perspectives and attitudes to the management of life.

Ella

Ella's frailty affects more emotional than physical aspects. The focus of Ella's story is on the feelings that are aroused in connection with the relationships she has in her life, primarily with her husband but also with her family and friends.

"Before, I could wash, wash dishes and change bedding but now I can't do it because of my frailty”

Her disabilities hinder her independence, and being a burden on others is a cause of concern and discomfort. Worry and anxiety are aroused about not having enough physical resources to cope with the care of her husband.

"Okay I'm the one who decides, but still you think it's a bit hard and [there are] difficult decisions to make, so then I have a little anxiety and worry that way, but otherwise, yes... Trying to be positive and not think and worry."

She expresses gratitude for her extensive social life, which is portrayed as being reasonably preserved despite her fragility. Without the illness, the importance of friends might not have been as clear to her. Despite close relationships, she experiences loneliness; although she stated that her attendance at church gives her relief and as sense of togetherness. Her discussion of heart surgery itself does not take a large proportion of Ella’s story, as her past life events have been more difficult in comparison.

"Yes, right here in the days when I was in the intensive care unit, or the infection ward it's called, then I was told I only had 48 hours to live and that was the worst time."

This is evident as Ella's own story is about the worry and gratitude in her relationships, and also the joy of being able to continue living.

Manfred

Manfred's story showed that his perceived physical and mental health after heart surgery was completely unchanged in all aspects, and his contented life attitude was clearly marked from a more difficult upbringing.

"I haven't thought even for a second about an operation. When I woke up, I was surprised that I had surgery and then the sister came and explained what they had done. But I had a good time before too, I can't complain about anything."

Gratitude was a common thread in the story of what life had given him, how it could have ended and all the good things he had been lucky enough to experience. Loved ones worried and supported a carefree Manfred, which can be interpreted as a reflection of Manfred's fragility that he himself was unaware of or did not want to talk about.

"They also said it's happened to me here in the house, and I don't remember anything. Not even when I woke up and they had to go behind me up the stairs, I thought it was no problem that I could fall, I've been counting on that, I'm also over 80."

The fragility, he admitted, he handled in his own way to the best of his ability. He had been unaware previously of the worry and anxiety that had always existed for him.

"One thing that annoys me a lot is that I'm so nervous. I don't know why. I don't have any evil or horrible things in front of me but still I'm nervous. That's not wise. I have a problem with that.”

As Manfred has not perceived any subjective health changes since heart surgery, it is assumed to have been vital, which indirectly gives great importance regarding Manfred's continued joy of living.

Lars-Göran

Lars-Göran is clear that he considers his family's health of higher value than his own. The importance of heart surgery was survival and a means to gain more time with his family.

“I’m glad I’m alive and very grateful for that. Got a lot of help at the hospital and I could have talked to a psychologist and stuff if I wanted, but it was good enough with the staff. They were great. They were wonderful people.”

The interview continued for a long time before it emerged, as if by chance, that some physical improvement had occurred thanks to the operation, which suggests that there were other more important things that Lars-Göran wanted to convey. Lars-Göran's theme was the care of his family and the desire to want to stay alive. Lars-Göran has also had a life marked by difficulties that have shaped him. Worry and anxiety, of varying origins, have been constant companions in his life. However, the insomnia that he suffered after heart surgery he believes is related to worry and anxiety of an existential nature. The fragility is palpable, but the desire to take care of his family seems to give him strength and direction.

"It's not that hard, I don't want to die. I want to continue living at least a few more years and experience [life with] these young children. Well, that's it. I'm not worried about myself, I'm worried about everything around [me]. I'm afraid of dying."

Irma

Irma is looking forward to continuing life after heart surgery, as she talks about all the things she now wishes to do with her life.

"I've probably lived a lot [with the mindset of] 'just one day, one moment at a time', so I haven't thought much ahead other than that it's getting better, and so I think if I practice a little bit more or try to go out for a little longer on walks, when the weather gets a little better, I'll feel better.”

Her husband's support enables her to resume the walks that contribute significantly to her joy of living now that her energy has returned. Irma's husband's supportive role regarding her frailty is clear, as he is often mentioned in the conversation in the context of an important supportive function. An unspoken concern can be interpreted from Irma's story regarding her many musings about complications after heart surgery. However, she expressed no pronounced concerns about heart disease itself or survival. It is difficult to interpret why, but could be because Irma has already thought about this in connection with more serious illness earlier in life, and then she may have learned that there is no point in worrying about the bigger and more important things.

" I don't feel fragile now, but I remember when I fell ill with one of those bleeding subarach something that then I felt very fragile … but not now. It was a difficult time."

At the time, she says, she was fragile, but not now. It is clear that Irma chooses to focus on taking care of her health and personal goals.

Discussion

The findings reflect four frail heart patients and their experience of health, worry and anxiety associated with surgery. Frailty grading is important for health professionals to take into account when considering outcomes following cardiac surgery in elderly patients [7]. In respect to the theme of the importance of heart surgery, patients’ stories showed how frailty affected their life situations and how this in turn had an impact on health. In some cases, frailty contributed to the need for help from loved ones or home care. A common experience of the participants was improved physical ability following cardiac surgery.

Coelho [14] describe significant improvements in physical ability in the first 3 months after heart surgery. Deteriorating health and old age before the operation had a negative impact on patients’ mental well-being. Rehabilitation programmes and patient counseling for the first 12 months after surgery were thus seen as beneficial in the recovery process [14]. Up to 10 years after heart surgery, both physical and psychological effects can still have a positive impact on quality of life [15].

Also on the theme of the importance of heart surgery, participants expressed gratitude and appreciation for having survived heart surgery and receiving an extension of life through improved health. Patients who are about to undergo heart surgery have both the hope of a ‘refreshment’ and an expectation of improved quality of life [5]. Garcia [16] believe that quality of life is an important component of recovery. Edeer [17] confirm this by demonstrating that patients who have undergone heart surgery are primarily focused on surviving the operation.

There are a number of known risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease, some of which are advanced age and avoidable factors [2].

The findings of this study are taken from older people who, with their stories, described gratitude for the chance of continued life. For everyone interviewed, the operation was of vital importance. From a socio-economic perspective, it becomes important for the health system to work preventively when it comes to factors that can be influenced to reduce the risk of recurring illness. One possibility of this, the authors believe, consists of providing patients with in-depth education that highlights health from various aspects and intends to strengthen patients’ ability to self-care after discharge. In doing so, patients are given the opportunity to return to their lives with a positive attitude to lifestyle changes Eriksson.

Under the theme "importance of relationships" worry about the family was the most prominent among the informants who described themselves as having a concern. This was explained by their own vitality and that the need for their presence for the family still existed. Cardiovascular disease and concomitant mental burden share a common epidemiology, although the relationship between biological and behavioral mechanisms has not yet been clarified. The background also showed that impaired social interaction leads to a poorer quality of life while social support and feeling meaningful with life can contribute to an improved quality of life.

Deteriorating social interactions result in poorer quality of life [18], while social support and finding meaning in life can contribute to improved quality of life [19]. Mohammadi [20] gave support to this by showing that participation from the family has a positive impact on patients who have undergone heart surgery. The participants experienced a passion and a more positive attitude towards life after their heart surgery when they had social support.

Undergoing heart surgery during the Covid-19 pandemic was limited by social restrictions. The desire to return to social interaction as soon as possible and regular visits to the Church contributed to a sense of social security in patients. Mohammadi [20] highlight the importance of to feel more hopeful about the future.

Sleep difficulty arising after surgery was caused by the worry of not wanting to leave the family due to possible death. An experience of anxiety before the operation and which in connection with the operation was reinforced by the fear of perhaps not surviving. Muthukrisanen show that difficulty with sleeping can last up to 3 months after heart surgery and that preoperative worry and anxiety are predictive of this. The findings indicate that sleep quality in these patients could be increased through their ability to manage their symptoms and a home environment conducive to good sleep. The background of the work showed that some sense of unease is expected in life but if the feeling is persistent and not commensurate with what triggered it, it can indicate anxiety disorders [21].

Ka Wai Lai [22] report that worry and anxiety in patients undergoing planned heart surgery can be reduced through preoperative information. Information contributes to the satisfaction of the patient as well as of the family, and can reduce the patient's anxiety. Peric [23] highlight that good sleep is a prerequisite for health improvements after heart surgery. The responsibilities of the intensive care nurse should include preparing the patient for possible sleep problems and explaining how self-care can promote this.

Under the theme of formative life events, participants described experience of frailty in illness earlier in life and fragility in serious illness. It is important to identify frail patients before surgery and adapt care throughout the course of care [24].

The newly-operated heart patient is at the mercy of the care unit and initially of the intensive care unit. Aslani [25] report that heart-operated patients stated that their basic needs were the most important ones to meet Patients had an expectation that healthcare professionals would be by their side when they woke up after surgery and that they would continually provide support and explanations, and show kindness. It emerged that intensive care staff needed to provide more psychological care. This is in the context of patients feeling that staff focused on the physical parameters [25]. Pedersen [26] showed that patients' trust in healthcare increased by meeting the same healthcare professionals, which reduced the risk of healthcare professionals saying different things. In this way, patients had a sense of security and reduced anxiety.

A strategic sample was applied, and the interview count in this study resulted in four participants as there was no access to more participants within a set time frame.

Lieblich [11] describe that few participants are consistent with narrative analysis. According to the Swedish National Agency for Medical and Social Evaluation [27], there are no rules for how large the sample should be in qualitative research; it is the information requirements that are indicative. The risk with many interviews is that they can lead to large and difficult-to- handle material [28].

Conclusion and Implications for clinical practice

In this study, fragile patients underwent heart surgery that resulted in physical improvements which in turn contributed to patients’ perceived health. The fragile patients' relationships with friends and family had a strengthening impact on recovery. Their life situations and previous experiences were central in informing their attitude to health, worry and anxiety associated with the operation.

Knowledge of how fragile patients experience health in connection with heart surgery contributes to the opportunity for health professionals to adapt their care and make it person- centred. Based on this knowledge, intensive care nurses can, in their nursing work, strengthen the patient's recovery throughout the intensive care process.

Funding

Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Linköping, Sweden financed this project.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank our four informant who wanted to share their experiences with us.

References

- Swedeheart Annual report. https://www.ucr.uu.se/swedeheart/117-%20swedeheart/1300-arsrapport-2020. 2020

- Kasprzak D, Rzezniczak J, Ganowicz T, et al. A review of acute coronary syndrome and its potential impact on cognitive function. Global Heart. 2021;16(1).

- Jahangiri M, Bilkhu R, Thirsk E, et al. Surgical aortic valve replacement in the era of transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a review of the UK national database. BMJ open. 2020;28(10).

- Chauvet-Gelinier JC, Bonin B. Stress, anxiety and depression in heart disease patients: a major challenge for cardiac rehabilitation. Ann of Physical and Rehab Med, 2016;60(1);6-12.

- Tigges-Limmer K, Sitzer M, Gummert J. Perioperative psychological interventions in heart surgery: opportunities and clinical benefit. Deutsches Ärzteblatt inte. 2021;118(19-20):339.

- Bjørnnes AK, Parry M, Falk R. Impact of material status and comorbid disorders on health-related quality of life after cardiac surgery. Qaul Life Res. 2017;26(9): 2421-34.

- Miguelena-Hycka J, Lopez-Menendez J, Prada PC. Influence of preoperative frailty on health-related quality of life after cardiac surgery. The Ann of Thoracic Sur. 2019;108(1):23-9.

- Reichart D, Rosato S, Nammas W, et al. Clinical frailty scale and outcome after coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 2018;54(6):1102-9.

- Neupane I, Arora RC, Rudolph JL. Cardiac surgery as a stressor and the response of the vulnerable older adult. Experimental Gerontology. 2017;87:168-74.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Lieblich A, Tuval-Mashiach R, Zilber T. Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Sage. 1998.

- Karataş T, Bostanoğlu H. Perceived social support and psychosocial adjustment in patients with coronary heart disease. Int journal of nursing practice. 2017;23(4):e12558.

- Muessig JM, Nia AM, Masyuk M, et al. (2018). Clinical frailty scale (cfs) reliably stratifies octogenarians in german icus: a multicentre prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatrics.13(1):S2-9.

- Coelho PN, Miranda LM, Barros PM, et al. Quality of life after elective cardiac surgery in elderly patients. Int CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery. 2019;28(2):199-205.

- Perrotti A, Ecarnot F, Monaco F, et al. Quality of life 10 years after cardiac surgery in adults: a long-term follow-up study. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2019;17(1):1-9.

- Garcia E, Rosell M, Ruiz E. The impact of frailty in aortic valve surgery. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20 (1):S-426.

- Edeer AD, Bilik Ö, Kankaya, E. Thoracic and cardiovascular surgery patients: Intensive care unit experiences. Nurs Crit Care. 2019;25:206-213.

- Jorge AJL, Rosa MLG, Correia DM. Evaluation of quality of life in patients with and without heart failure in primary care. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2017;109:248-52.

- Liu MH, Chiou AF, Wang CH, et al. Relationship of symptom stress, care needs, social support, and meaning in life to quality of life in patients with heart failure from the acute to chronic stages: a longitudinal study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2021;19:1-1.

- Mohammadi N, Abbasi M, Nikbakht NA et al. Passion for life: lived experiences of patients after coronary artery bypass graft. The J of Tehran Heart Center. 2015;10(3):129.

- Pittig A, Treanor M, LeBeau RT. The role of associative fear and avoidance learning in anxiety disorders: gaps and directions for future research. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2018;88:117-40.

- Lai VK, Ho KM, Wong WT, et al. Effect of preoperative education and ICU tour on patient and family satisfaction and anxiety in the intensive care unit after elective cardiac surgery: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2021;30(3):228-35.

- Peric V, Stolic R, Jovanovic A, et al. Predictors of quality of life improvement after 2 years of coronary artery bypass surgery. Annal of Thor and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2017;23(5):233-8.

- Birkelbach O, Mörgeli R, Spies C, et al. Routine frailty assessment predicts postoperative complications in elderly patients across surgical disciplines–a retrospective observational study. BMC anesthesiology. 2019;19(1):1-0.

- Aslani Y, Nikinejad R, Moghimian M, et al. An investigation of the psychological experiences of patients under mechanical ventilation following open heart surgery. ARYA Athersclerosis. 2017;16 (6):274-281.

- Pedersen SS, Knudsen C, Dilling K, et al. Living with an implantable cardioverter defibrillator: patients' preferences and needs for information provision and care options. Ep Europace. 2017;19(6):983-90.

- The Swedish National Agency for Medical and Social evaluation (2020). The method manual. https://www.sbu.se/pubreader/pdfview/display/48286?browserprint=1

- Kvale, S. & Brinkmann, S. The qualitative research interview. Student literature. 2014.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref