Original Article - Archives of Digestive Disorders (2017) Archives of Digestive Disorders (Special Issue 1-2017)

Prevalence and risk factors of new onset diabetes after liver transplantation (NODAT): A single Egyptian center experience

Reham Adly Zayed1, Monir Hussein Bahgat1*, Mohammed Abdel Wahab21Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Specialized Medical Hospital, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, 35516, Egypt

2Gastroenterology Surgery and Liver Transplantation Unit, Gastrointestinal Surgery Center, Mansoura University, Mansoura, 35516, Egypt

3Internal Medicine Department and Liver Transplantation Unit, Gastrointestinal Surgery Center, Mansoura University, Mansoura 35516, Egypt

- *Corresponding Author:

- Monir Hussein Bahgat

Division of Hepatology and Gastroenterology

Specialized Medical Hospital, Mansoura University

Mansoura

Egypt

Tel: +2 01111196919

Fax: +2-050-2230129

E-mail: monirbahgat@gmail.com

Accepted date: January 19, 2017

Citation: Zayed RA, Bahgat MH, Wahab MA, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of new onset diabetes after liver transplantation (NODAT): A single Egyptian center experience. Arch Dig Disord. 2017;1(1):7-13

Abstract

Aim: To estimate the prevalence of New Onset Diabetes after Liver Transplantation (NODAT) and to investigate the possible risk factors. Methods: This retrospective study comprises 213 patients subjected to living donor liver transplantation (LDLT). Patients’ data were collected from medical registry files for a period of two years after transplant. Results: Of the total 213 recipients, complete data for the whole study period were available for 164 recipients who were enrolled in this study. Fifty one 51 (31.1%) patients were already diabetic prior to transplantation. The prevalence of NODAT was 27.43% (31/113). Eight of NODAT cases (25.8%) were transient with recovery within 6-months period in 5/8 cases while the other 3 cases recovered in more than 6 months to a year. The only drug that showed statistically significant difference was tacrolimus (p=0.02). Interestingly, three pre-transplant diabetics (3/51, 5.9%) recovered after liver transplant with elimination of their anti-diabetic therapy. Conclusion: NODAT is a common medical complication that occurs in 27.4% of liver transplant recipients. The study suggests using one year cutoff rather than 6 months for defining transient NODAT. Post-transplant tacrolimus-based immunosuppression is a significant independent predictor of NODAT development

Keywords

New onset diabetes, Liver transplantation, Chronic liver disease, Immunosuppression drugs, Tacrolimus

Introduction

The high prevalence of chronic liver disease (CLD) in Egypt has led to increasing number of patients suffering from endstage liver disease for which Liver transplantation (LT) is the most effective treatment [1]. This surgery carries a risk of many significant complications including new-onset diabetes mellitus after liver transplantation (NODAT) which has a great variation in its incidence across different studies that ranged from 2% to 53% [2-6]. This variation might be explained by many factors that include reporting bias, small sample sizes, and how NODAT was defined.

Many other factors were blamed to increase the risk for NODAT including family history of DM, patient’s age, immunosuppressive regimen used, obesity, ethnicity, and etiology of CLD [7-11]. When NODAT develops, patients should be closely monitored to differentiate between transient and persistent NODAT albeit there is no agreement to date for the definition of transient NODAT [12-14]. To the best of our knowledge, no data describing NODAT following living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) in Egypt had been published. Therefore, this retrospective study was conducted to estimate the prevalence and possible risk factors of NODAT in our population.

Patients and Methods

Patients

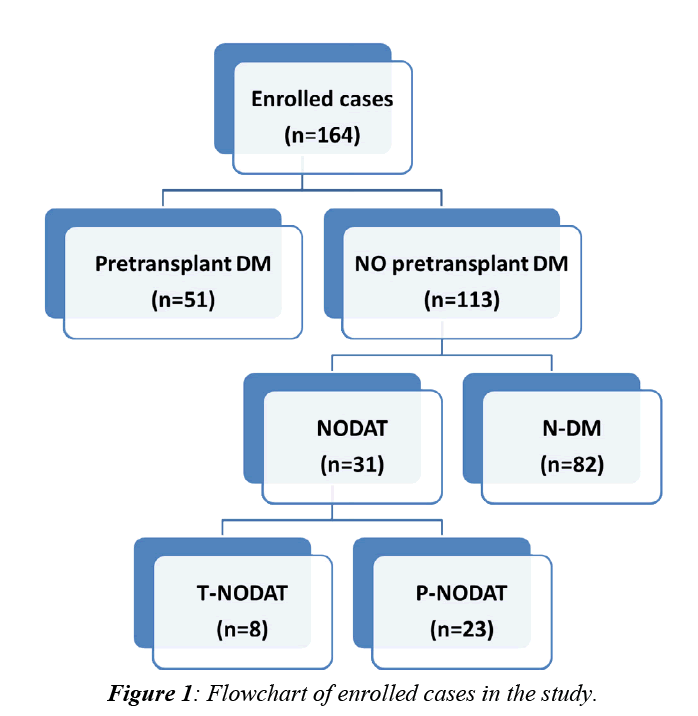

This retrospective study comprises a total number of 213 patients subjected to LDLT at Mansoura Gastroenterology Surgical Center from May, 2004 to January, 2013. Patients’ data were collected from the database system of the transplantation unit. Approval of ethical scientific committee in Faculty of Medicine, Mansura University was obtained. Of these 213 patients, 164 patients were enrolled while the remaining 49 patients (23%) were excluded either due to early mortality (16%) or due to lack of follow up (7%). Out of the enrolled 164 patients, 51(31.1%) were diabetic prior to LDLT while the remaining 113 patients (68.9%) were not. A flowchart for enrolled cases was illustrated in (Figure 1).

For all patients, the following data were reviewed and recorded at enrollment and for two years after LDLT:

A. Thorough review of history taking with special stress on; age, sex, detailed history of DM, family history of DM, and indication for liver transplantation.

B. Thorough review of physical examination with special stress on BMI, stigmata of CLD, and presence of diabetic complications.

C. Reporting of available laboratory investigations with special stress on ABO and Rh Blood groups for donor and recipient, complete blood count (CBC), prothrombin Time (PT), International Standardized Ratio (INR), serum fasting (FBG) and post prandial (PPG) blood glucose (mg/dl), albumin (gm/dL), AST (IU/L), ALT (IU/L), total bilirubin (mg/dL), GGT (IU/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (KAU), serum creatinine (mg/dl), Alpha-fetoprotein, Anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), antimitochondrial antibody (AMA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA), viral serological markers (HBsAg, Anti-HBc, and HCV Antibody) as well as quantification of serum HCV-RNA and HBV DNA.

D. The date of onset of NODAT was assumed to be the date of earliest report of diabetes mellitus after liver transplantation [15]. Diagnosis of NODAT was based on the American Diabetes Association (ADA) definition of diabetes mellitus (FBG level of ≥126 mg/dl on two consecutive occasions, and/or PPG level of ≥200 mg/ dl in the OGTT) [16]. Results of blood glucose levels were reported throughout the first two years after liver transplantation to detect the optimum time for diagnosis of transient NODAT.

E. Reporting available radiological studies including abdominal ultrasonography (US), tri-phasic computerized tomography (CT) of abdomen, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of abdomen.

F. All patients were assessed by Child Turcott Pugh (C.T.P) score [17] and Model for End stage liver disease (MELD) score [2,18].

G. Detailed drug history with special stress on immunosuppressive, and anti-hyperglycemic agents.

Statistical analysis

Collected Data were entered and analyzed using an SPSS software version 17. Qualitative data were expressed as numbers and percentages and were compared using Chi-square (or Fisher's exact) test. Quantitative data were initially tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilk and considered as normally distributed if p>0.05. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD if normally distributed or median if not and were compared using independent samples t-test for two groups or one way ANOVA test for more than two groups if normally distributed or using the alternative nonparametric tests (Mann-Whitney U and Kruskal-Wallis tests respectively) if not. Univariate logistic regression models were used to predict the associations between outcomes and different variables. Multivariate analysis was done for the associations between outcomes and significant variables on univariate analysis. Statistical significance was defined as p value ≤ 0.05.

Results

Based on the flowchart (Figure 1), our enrolled cases (n=164) were classified into 3 groups:

1. N-DM (n=82): Those who were not diabetic prior to LDLT and remained so during the whole two-year period of follow up after surgery.

2. Pre-transplant DM (n=51): Those who were diabetic prior to LDLT. This group was further subdivided into:

a. Recovered pre-transplant DM (n=3).

b. Persistent pre-transplant DM (n=48).

3. NODAT (n=31): Those who were not diabetic prior to LDLT but developed DM after surgery. This group was further subdivided into:

a. Transient NODAT [T-NODAT] (n=8): Those who recovered during the study period.

b. Persistent NODAT [P-NODAT] (n=23): Those who didn’t recover during the study period.

The clinical and laboratory characteristics of the enrolled cases

Table 1 showed a statistically significant difference between the three groups for age (p=0.003), and pre-transplant FBG (p<0.0001). Post-hoc analysis of these data showed that age was significantly higher in pre-transplant DM group than N-DM group only (p<0.001) while FBG was significantly higher in pre-transplant DM group than the two other groups (p<0.0001). Also, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) showed significant difference between the three groups (p=0.043). It was diagnosed in 25/51 (49%) of pre-transplant DM patients and in 33/113 (29.2%) of those without pre-transplant DM. This difference was statistically significant (X2=6.057, p=0.014), and the presence of pre-transplant DM increased the risk of HCC by two-fold (B=0.845, p=0.015, Odds=2.331). Among patients with no pre-transplant DM, HCC was diagnosed prior to LDLT in 9/31 (29.0%) of NODAT cases and in 24/82 (29.3%) of N-DM cases. This difference was not statistically significant (X2=0.001, p=0.98).

Table 1: Clinical and biochemical baseline characteristics of 3 different groups.

| Parameter | NODAT (n=31) | N-DM (n=82) | Pre-transplant DM (n=51) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count (%) | ||||

| Gender: Male Female | 28 (90.32%) 3 (9.67%) | 72 (87.80%) 10 (12.19%) | 44 (86.27%) 7 (13.72%) | 0.863 |

| Pre-transplant HCV | 30 (96.77%) | 71 (86.58%) | 48 (94.11%) | 0.299 |

| Pre-transplant HBV | 1 (3.20%) | 8 (9.75%) | 4 (7.84%) | 0.511 |

| Pre-transplant HCC | 9 (29.03%) | 24 (29.26%) | 25 (49.01%) | 0.043 |

| Pre-transplant hypertension | 5 (16.19%) | 3 (3.65%) | 1 (1.90%) | 0.844 |

| Median | ||||

| Age (years) | 50 | 47.5 | 52 | 0.003 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.49 | 30.07 | 28.01 | 0.367 |

| FBG | 96 | 93 | 136 | <0.0001 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 46 | 33.50 | 40 | 0.519 |

| AST (IU/L) | 73.50 | 61.50 | 64 | 0.355 |

| S. Albumin (gm/dL) | 3.0 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.412 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (KAU) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0.549 |

| GGT(IU/L) | 32 | 28 | 38 | 0.435 |

| Bilirubin(mg/dl) | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 0.066 |

| INR | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.453 |

| S. creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.606 |

Donor characteristics and development of NODAT

Table 2 showed that there was no significant differences in donor characteristics between NODAT and N-DM groups.

Table 2: Effect of donor characteristics on the development of NODAT in recipients.

| NODAT (n=31) | N-DM (n=82) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age | 27 | 28 | 0.547 |

| Sex Male Female | 28 (90.32%) 3 (9.67%) | 61 (74.39%) 21 (25.60%) | 0.07 |

| Donor BMI (kg/m2) | 26.77 ± 3.24 | 26.77 ± 3.24 | 0.614 |

| Relation to donor Unrelated First degree Second degree Third degree Fourth degree | 11/38 9/34 2/15 5/15 4/11 | 27/38 25/34 13/15 10/15 7/11 | 0.688 |

| ABO similarity Different Similar | 9 (29.0%) 22 (71%) | 21 (25.6%) 61 (74.4%) | 0.713 |

| Rh similarity Different Similar | 2 (6.5%) 29 (93.5%) | 10 (12.2%) 72 (87.8%) | 0.506 |

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) and development of NODAT

HCV was present in 71/82 (86.6%) of N-DM group versus 30/31 (96.8%) of NODAT group (X2=2.460, p=0.117). HCV recurrence was diagnosed in 61/71 (85.9%) of N-DM group versus 28/30 (93.3%) of NODAT group (X2= 1.108, p=0.292).

Immunosuppressive agents and NODAT

Table 3 showed that only use of tacrolimus was statistically significantly different (X2= 5.355, p=0.021) between NODAT group (26/31, 83.9%) and N-DM group (50/82, 61%). Simple logistic regression revealed that use of tacrolimus increased the risk of NODAT by 3.3 times (B=1.202, Wald=4.990, p=0.025, Odds=3.328). Multivariable logistic regression analysis incorporating age, pre-transplant FBG, and tacrolimus use revealed that tacrolimus was the only independent risk factor for the development of NODAT.

Table 3: The effect of immunosuppressive drugs on NODAT.

| NODAT (n=31) | N-DM (n=82) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | No (%) | ||

| Tacrolimus | 26 (83.9%) | 50 (61%) | 0.021 |

| Cyclosporine A | 7 (22.58%) | 30 (36.58%) | 0.157 |

| Everolimus | 7 (22.58%) | 20 (24.39%) | 0.840 |

| Corticosteroids | 13 (41.93%) | 33 (40.42%) | 0.870 |

| MMF/ MPA | 29 (93.54%) | 70 (85.36%) | 0.343 |

| Methylprednisolone | 6 (19.35%) | 9 (10.79%) | 0.241 |

Anti-diabetic therapy of NODAT

Of the 31 NODAT patients, 19 cases were treated with oral hypoglycemic agents, 10 cases were treated with insulin therapy and only two cases were treated with oral hypoglycemic agents initially then shifted to insulin therapy. Insulin was used in cases with impaired graft function, presence of infection or rejection.

T-NODAT (n=8) versus P-NODAT (n=23)

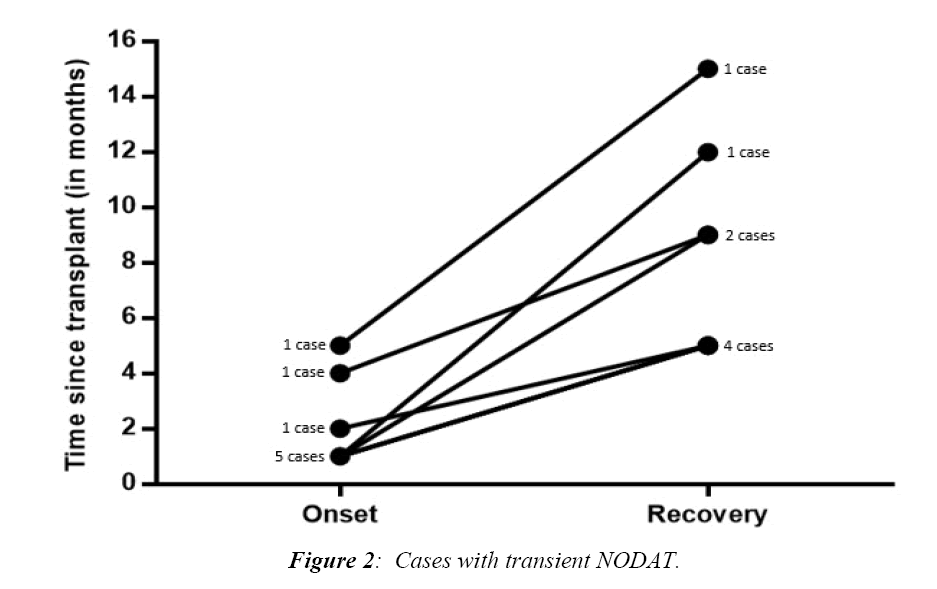

Figure 2 illustrated the times of onset and recovery of transient cases of NODAT. Most cases were diagnosed one month after surgery (5/8, 62.5%) while the other 3 cases were diagnosed after 2, 4, and 5 months. The minimum duration of T-NODAT reported in our cohort was 3 months, and the maximum was 11 months.

Table 4 showed that there was no statistically significant difference in clinic-laboratory data between P-NODAT and T-NODAT.

Table 4: Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the P-NODAT vs. T-NODAT.

| Parameter | Persistent NODAT (n=23) | Transient NODAT (n=8) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD, No (%)or median | ||||

| Age(years) | 48.39 ± 6.807 | 50.63 ± 5.854 | 0.416 | |

| Sex* | 0.550 | |||

| Male | 20 (71.42%) | 8 (28.57%) | ||

| Female | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| BMI (Kg/m2)* | 31.221 | 28.405 | 0.259 | |

| ALT (IU/L)* | 34.50 | 60.50 | 0.655 | |

| AST (IU/L)* | 52.0 | 90.50 | 0.467 | |

| S. Albumin (gm./dL) | 3.02 ± 0.605 | 2.81 ± 0.379 | 0.369 | |

| Alkaline phosphatase (KAU) | 5.0 | 6.0 | 0.249 | |

| GGT(IU/L) | 32.0 | 33.0 | 0.677 | |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 2.60 | 4.60 | 0.190 | |

| INR | 1.60 | 1.55 | 0.786 | |

| S.creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.221 | |

| Etiology of liver disease HCV HBV HCV+ HCC | 15 (65.21% ) 1 (4.34% ) 7 (30.43%) | 6 (75% ) 0 (0%) 2 (25% ) | 0.782 | |

| Immunosuppression Tacrolimus Cyclosporine Everolimus Corticosteroids MMF/ MPA Methylprednisolone | 19 (67%) 3 (50%) 5 (71.42%) 8 (61.53%) 20 (71.42%) 4 (66.66%) | 6 (24%) 3 (50%) 2 (28.57) 5 (38.46%) 8 (28.57%) 2 (33.33%) | 0.589 0.300 1.00 0.242 1.00 0.645 | |

| Anti-diabetic medication Oral Insulin Oral then shift to insulin | 14 (60.9%) 7 (30.4%) 2 (8.7%) | 5 (62.5%) 3 (37.5% ) 0 (0% ) | 0.674 | |

* Median (as it is non-Gaussian)

Discussion

Using the ADA definition of diabetes mellitus, the prevalence of NODAT in our study was 27.43% (31/113); these results are in accordance with other previously published data that ranged from 2 to 53% in solid organ transplantation, about 4 to 25% in renal transplantation, and 2.5 to 25% in liver transplantation [2-6].

Although some studies [19,20] introduced FBG as an independent risk factor for NODAT, our cohort had slightly higher FBG which was statistically insignificant in NODAT group. This lack of significance might be explained by the fact that all cirrhotic patients are at increased risk for fasting hypoglycemia that may blunt the rise in FBG as risk factor for later development of NODAT.

In a similar way, increased recipient' age was not associated with NODAT. This is contrary to Sumrani et al. [20]and Reisaeter et al. [21] who reported that age >40 years is considered an independent risk factor of developing NODAT. On the other hand, Lv et al. [19] reported a similar result to our study. This difference between studies might be explained by different sample sizes, selection bias, and presence of confounders as comorbidities. Gender, as well was an independent risk factor for NODAT in this and other studies.

Moreover, a BMI >25 kg/m2 was found to be associated with an high risk of NODAT in the study by Saliba et al. [22] and was later confirmed by Oufroukhi et al. [23]. However, our study didn’t prove this association which was in agreement with the results of the study by Lv et al. [19]. This conflicting results between different studies might be explained by the lack of accuracy of BMI in diagnosing overweight and obesity in patients with advanced cirrhosis.

In our study, none of the components of CTP and MELD, had statistically significant difference between those who developed NODAT and those who remained non-diabetic (N-DM group). Similarly, differences between alkaline phosphatase, GGT, ALT, AST, etiology of liver disease and pre-transplant hypertension were all insignificant.

Although HCV recurrence was reported to be associated with the development of NODAT [24,25], this relationship was not confirmed in our study when comparing NODAT and N-DM groups for HCV etiology at enrollment for LDLT and HCV recurrence after surgery. Therefore, we suggest another study that compare the effect of newer direct acting anti-viral drugs and achievement of sustained virological response (SVR) before transplantation on the later development of NODAT after surgery.

Cosio et al. [25] reported that the stress of surgery and use of immune-suppressive medications can cause hyperglycemia in the recipients. This hyperglycemic state will not persistent in all cases, instead the term transient NODAT is used to define the state of hyperglycemia that started and ended within the first year of transplantation [26-28]. However, Honda et al. [13] defined transient NODAT as termination of treatment of hyperglycemia within six months after the diagnosis. We aimed at studying this time frame in our cohort and according to our results, T-NODAT was diagnosed 1-5 months after surgery, and recovered in 3-11 months after diagnosis. Therefore, we adopt a new definition for T-NODAT as a state of hyperglycemia that developed within 6 months after transplantation and recovered in less than 1 year duration that needs a large-scale study to confirm this new definition.

Our results were consistent with the previously published data regarding the diabetogenic effect of tacrolimus and its role in the development of NODAT and against the conclusion coined by Mirabella et al. [29] that tacrolimus has no role in occurrence of NODAT [30-34]. Therefore, tacrolimus remained, according to previous and our own results, an independent risk factor for NODAT. Contrary to tacrolimus, using everolimus was not associated with the development of NODAT [34] and there is a trend to incorporate everolimus in the immunosuppressive regimen in liver transplant recipients in our institute to minimize the adverse effects including nephrotoxicity. Also, although some studies suggested that administration of posttransplantation high dose corticosteroids as a risk factor for NODAT [9], this was not proved in our cohort which might be attributed to the use of smaller doses for a short period. Similarly, MMF/MPA was not associated with the occurrence of NODAT.

In our study, presence of pre-transplant DM increased the risk of HCC by two-folds than those who were not diabetic. This goes with the pooled risk estimate of 17 case-control studies with OR of 2.40 [34]. For those who were not diabetic at time of surgery. The presence of pre-transplant HCC had no statistically significant difference between those who developed NODAT and those who remained non-diabetic. This goes also with the results of Ling et al. study [34] from China where the presence of HCC increased the risk of NODAT by 1.2 on univariate analysis but not on multivariate analysis. Therefore, type 2 DM would be a risk factor for HCC while HCC per se would not be a risk factor for NODAT.

To date, our governmental policy allowed living donor transplantation from only patients’ relatives. Analysis of blood group matching and degree of consanguinity between the recipient and donor showed no effect on the development of NODAT.

The main stay of treatment of NODAT in our cohort followed the well-established treatment policy of type 2 DM worldwide relying upon oral agents with the use of insulin being limited to those who have severe hyperglycemia from the start or those who developed post-operative complications especially infections as well as those who were not controlled on oral agents. This confirms that treatment of NODAT would not be different from that of type 2 diabetes.

Interestingly, successful LT led to complete recovery of diabetes in three patients with pre-transplant DM (5.9%). One explanation for this finding would be the elimination of the diabetogenic effect of liver cirrhosis (hepatogenous diabetes) after LDLT. More explanations await further studies.

Our study has several strengths, including the specific Egyptian population and being census study involving all transplant surgeries performed over a decade, but also some limitations. Firstly, the study was conducted in a single center for a limited time period resulting in a small sample size. Secondly, the study population was predominantly hepatitis C-based. Thirdly, some important data such as serum magnesium and blood levels of calcineurin inhibitor were not routinely recorded in hospital database and thus were missing. Finally, this is an observational study in nature and the basis of every important finding still needs to be further explained.

Conclusion

NODAT is a common medical complication occurring in the recipients of LDLT in Gastroenterology Surgical Center, Mansoura University. So screening of NODAT is mandatory. It might be either persistent or transient resolving within one year. Patients with NODAT should be strictly followed up to differentiate transient form persistent NODAT. Post-transplant immunosuppression using tacrolimus plays a cardinal role in the occurrence of NODAT and other drugs as everolimus, cyclosporine A and MMF/ MPA were not found to be independent risk factors for NODAT. On the other hand, those with pre-transplant diabetes might recover after transplantation.

Author Contributions

Bahgat MH, contributed to selection of topic of the research, its deign, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafted the article and revised it. Wahab MA, contributed to surgical intervention procedures. Zayed RA, El-Etreby SA, Saad RA, Elmorsy FM, and contributed to collection of data from medical database of Gastroenterology Surgery & liver transplantation unit, wrote the manuscript and analysis of the data. Bahgat MH, contributed to statistical analysis of all data.

Supportive Foundation

Specialized Medical Hospital and Gastrointestinal Surgery Center, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research described in this paper.

References

- El-Gazzaz, GH, El-Elemi AH. Liver transplantation in Egypt from West to East. Transplant Research and Risk Management. 2010;2:41-46.

- Huo TI, Lin HC, Wu JC, et al. Proposal of a modified Child-Turcotte-Pugh scoring system and comparison with the model for end-stage liver disease for outcome prediction in patients with cirrhosis. Liver transplantation. 2006;12(1):65-71.

- Baid S, Cosimi AB, Farrell ML, et al. Posttransplant diabetes mellitus in liver transplant recipients: Risk factors, temporal relationship with hepatitis C virus allograft hepatitis, and impact on mortality. Transplantation 2001;72(6):1066-1072.

- Montori VM, Basu A, Erwin PJ, et al. Posttransplantation diabetes a systematic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):583-592.

- Davidson J, Wilkinson A, Dantal J, et al. New-onset diabetes after transplantation: 2003 international consensus guidelines1. Transplantation. 2003;75(10):SS3-SS24.

- Marchetti P. New‐onset diabetes after liver transplantation: From pathogenesis to management. Liver Transplantation. 2005;11(6):612-620.

- Bigam DL, Pennington JJ, Carpentier A, et al. Hepatitis C–related cirrhosis: A predictor of diabetes after liver transplantation. Hepatology 2000;32(1):87-90.

- Khalili M, Lim JW, Bass N, et al. New onset diabetes mellitus after liver transplantation: The critical role of hepatitis C infection. Liver Transplantation. 2004;10(3):349-355.

- AlDosary AA, Ramji AS, Elliott TG, et al. Post liver transplant diabetes mellitus: An association with hepatitis C. Liver Transplantation. 2002;8:356-361.

- Sarno G, Mehta RJ, Guardado-Mendoza R, et al. New-onset diabetes mellitus: Predictive factors and impact on the outcome of patients undergoing liver transplantation. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2013;9(1):78-85.

- Kiberd M, Panek R, Kiberd BA. New onset diabetes mellitus post-kidney transplantation. Clinical Transplantation. 2006;20(5):634-39.

- Kesiraju S, Paritala P, Raoch UM, et al. New onset of diabetes after transplantation - an overview of epidemiology, mechanism of development and diagnosis. Transpl Immunol. 2014;30(1):52-8.

- Honda M, Asonuma K, Hayashida S, et al. Incidence and risk factors for new-onset diabetes in living-donor liver transplant recipients. Clinical Transplant

- Kuo HT, Christine Lau C, Sampaio MS, et al., Pretransplant risk factors for new-onset diabetes mellitus after transplant in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Liver Transplantation. 2010;16:1249-1256.

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):S81-S90.

- Pugh RNH, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, et al. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. British J Surgery. 1973;60(8):646-649.

- Freeman RB, Wiesner RH, Harper A, et al. The new liver allocation system: moving toward evidence-based transplantation policy. Liver Transplantation. 2002;8(9):851-858.

- Lankarani KB, Eshraghian A, Nikeghbalian S, et al. New onset diabetes and impaired fasting glucose after liver transplant: risk analysis and the impact of tacrolimus dose. Exp Clin Transplant. 2014;12(1):46-51.

- Lv C, Zhang Y, Chen X, et al. New-onset diabetes after liver transplantation and its impact on complications and patient survival. J Diabetes 2015;11.

- Sumrani NB, Delaney V, Ding Z, et al. Diabetes mellitus after renal transplantation in the cyclosporine era. Transplantation. 1991;51(2):343-347.

- Reisaeter A, Hartmann A. Risk factors and incidence of posttransplant diabetes mellitus. Transplantation Proceedings. 2001;33(5):S8-S18.

- Saliba F, Lakehal M, Pageaux GP, et al. Risk factors for new‐onset diabetes mellitus following liver transplantation and impact of hepatitis C infection: An observational multicenter study. Liver Transplantation. 2007;13(1):136-144.

- Oufroukhi L, Kamar N, Muscari F, et al. Predictive factors for posttransplant diabetes mellitus within one-year of liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2008;85(10):1436-1442.

- Bloom RD, Lake JR. Emerging issues in hepatitis C virus-positive liver and kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(10):2232-2237.

- Cosio FG, Kudva Y, van der Velde M, et al. New onset hyperglycemia and diabetes are associated with increased cardiovascular risk after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int. 2005;67(6):24-21.

- Magy N, Cribier B, Schmitt C, et al. Effects of corticosteroids on HCV infection. International J Immuno pharmacology. 1999;21(4):253-261.

- Kasiske BL, Chakkera HA, Louis TA, et al. A meta-analysis of immunosuppression withdrawal trials in renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(10):1910-7.

- Pascual J, Galeano C, Royuela A, et al. A systematic review on steroid withdrawal between 3 and 6 months after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;90(4):343-349.

- Mirabella S, Brunati A, Ricchiuti A, et al. New-onset diabetes after liver transplantation. Transplantation Proceedings. 2005;37(6):2636-37.

- Vivarelli M, Dazzi A, Cucchetti A, et al. Sirolimus in liver transplant recipients: A large single-center experience. Transplantation Proceedings. 2010;42(7):2579-84.

- Davidson JA, Wilkinson A. New-onset diabetes after transplantation 2003 international consensus guidelines an endocrinologist’s view. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(3):805-812.

- Pallayova M, Wilson V, John R, et al. Liver transplantation: A potential cure for hepatogenous diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2013:e97-e97.

- Wang P, Kang D, Cao W, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28:109-122.

- Ling Q, Xu X, Xie H, et al. New-onset diabetes after liver transplantation: a national report from China Liver Transplant Registry. Liver Int. 2016;36:705-712.