Research Article - Current Pediatric Research (2017) Volume 21, Issue 3

Prevalence and distribution of active trachoma among children 1-9 years old at Leku town, southern Ethiopia.

Teshome Abuka Abebo1* and Dawit Jember Tesfaye21School of Public and Environmental Health, Hawassa University College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ethiopia.

2School of Public and Environmental Health, Hawassa University College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ethiopia.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Teshome Abuka Abebo

School of Public and Environmental Health

Hawassa University College of Medicine and Health

Sciences,

Ethiopia.

Tel: +251911043662

E-mail: teshabuka@gmail.com

Accepted date: July 26, 2017

Abstract

Background: Trachoma, one of the neglected tropical diseases, is a major public health problem in developing countries. Ethiopia has the highest prevalence of active trachoma and it is endemic in 604 rural districts with 73,164,159 people being at risk of infection. However, in the study area, the prevalence and distribution of active trachoma for children 1-9 years old were not known. Therefore, this study was intended to describe prevalence and distribution of active trachoma among children 1-9 years old at Leku town Southern Ethiopia. Methods: Community-based cross-sectional study was conducted at Leku town from June 1 to July 15, 2016. Systematic random sampling was used to select study participants. Each selected child 1-9 years old was clinically examined for active trachoma. Data were collected by using pre-tested questionnaire and observation. SPSS version 20 computer software was used to enter data into the computer and data analysis. Results: The overall prevalence of active trachoma among children 1-9 years old found to be 11.0% (Trachomatous inflammation- Follicular 9.8% and Intense 1.2%). Educational status of the household head (X2=12.4, p-value=0.006), economic status of the household (X2=4.55; p-value=0.033), soap use for children’s face washing (X2=5.28 p-value=0.021) and children’s facial cleanness (X2=75.6, p-value=0.000) had significant association with prevalence of active trachoma. Conclusion: In this study, the prevalence of active trachoma is above WHOs’ cutoff point to commence mass antibiotic (azithromycin) distribution combined with measures to encourage facial cleanness and improve sanitation in the affected community. In the meantime, the current study prevalence indicated that trachoma is a public health problem in the study area. While we recommend further studies to be conducted using optimum sample size to compute more accurate population level prevalence and identify risk factors in the study area.

Keywords

Active trachoma, Children, Prevalence, Distribution.

Introduction

Trachoma is chronic conjunctivitis caused by chlamydial trachomatis serovar A, B, Ba or C. Transmission occurs primarily through close personal contact, particularly among young children in rural communities with limited water supplies [1]. Trachoma remains major public health problem in 42 countries and responsible for the blindness or visual impairment of about 1.9 million people. It causes about 1.4% of all blindness worldwide [2]. Africa remains the most affected continent. Trachoma is known to be a public health problem in the 27 countries of WHO’s Africa Region in 2016. The countries with the highest prevalence of disease are in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in the Sahel belt and East Africa [3]. More than 83 million people in Africa were treated with antibiotics for trachoma in 2016, accounting for 97% of all antibiotic treatments for trachoma across the globe [2].

Ethiopia has one of the highest prevalence of active trachoma. It remains one of the major health problems, and a leading cause of blindness, in the country [4]. According to 2010 WHO report on neglected tropical diseases, Ethiopia ranks first in the list of high burden SSA countries [5]. Ethiopia together with four other countries bears half of the global burden of active trachoma [6]. The 2007 national survey showed the prevalence of active trachoma (Trachomatous Inflammation- Follicular (TF) and Trachomatous Inflammation- Intense (TI)) for children 1-9 years old is 40.14% and it is widely distributed in the country. Also the national survey pointed out the highest prevalence in Amhara region (62.6%) followed by Oromia region (41.3%) [7]. Additionally, other studies conducted in the country showed the prevalence of active trachoma for children 1-9 years were 12.53% (TF) and 9.98% (TI) in Mojo and Lum district, 24.1% in Baso Liben District, 23.1% (TF) and 22.5% (TI) in Gonji Kolella district and 36.7% in Zala District [8-11]. A region-wide study conducted in Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) revealed the prevalence of active trachoma among children 1-9 years old was 25.9% and the highest prevalence 48.5% were observed in Amaro and Burji Districts [12]. These literatures indicate that trachoma is public health problem in Ethiopia and provision of comprehensive intervention.

In 1996, World Health Organization (WHO) launched WHO alliances aim to eliminate trachoma as a public health problem globally by 2020. The elimination strategy is encapsulated by the acronym "SAFE": Surgery for advanced disease, Antibiotics to clear C. trachomatis infection, Facial cleanliness and Environmental improvement to reduce transmission. Consequently, the estimated number of people living in endemic districts, at risk of trachoma blindness, has declined from 317 million in 2010 to 200 million in 2016 [2]. District level active trachoma prevalence (TF) is recommended by WHO to guide the need for A, E and F components of SAFE strategies. When the prevalence of TF>10% in children 1-9 years old, WHO recommends mass administration of azithromycin annually for at least three years, combined with interventions to encourage facial cleanness and improve environmental sanitation in the affected community. This study aimed to describe district level prevalence and distribution of active trachoma in Leku town, Southern Ethiopia.

Methods and Materials

Study Setting and Design

Community-based cross-sectional study was conducted at Leku town, Southern Ethiopia from June 1 to July 15/2016. Leku town, administrative center of Shebedino district, is located 27 km far from Hawassa, the capital city of the Southern region of Ethiopia. The area coverage of the town is 700 hectares and its altitude is 1700 m above sea level. The town has three kebeles with a total population of 26,000. Of the total population, 6,455 were children of 1-9 years old. The source population of the study was all children 1-9 years old who reside in Leku town.

Sample Size and Sampling Procedure

The sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula with the assumption of 95 % confidence interval, 0.05 margin of error, 12% prevalence of active trachoma and 10% non-response rate [13]. The final computed sample size was 178. One kebele was selected from the three Kebeles found at Leku town by lottery method. Systematic random sampling was used to select households, where children 1-9 years old reside. The first household was selected by lottery method and from that systematically continued by visiting every ten house. In each household a child who fulfilled the inclusion criteria was examined for active trachoma. Children who were critically ill and unable to attend for eye examination were excluded from the study.

Study Variables

The dependent variable of this study was presence of active trachoma. The independent variables were sociodemographic characteristics, frequency of washing face, using soap for washing, facial cleanness, water source, distance of water source, household water consumption, latrine, waste disposal sites, cattle ownership of the household, presence of cattle in the living room, cooking place in the living room and presence of window in the cooking room.

Operational Definitions

Clean face-a child who does not have an eye discharge or nasal discharge at the time of the survey.

Free from active trachoma-children that do not have signs and symptoms of active trachoma.

Active trachoma: TF has been suggested by WHO as the key indicator for assessing the public health importance of active trachoma. Hence, it was defined as the presence of at least five or more follicles in the upper tarsal conjunctiva each at least 0.5 mm in size.

Data Collection and Quality Assurance

Structured questionnaire-based interview, observation and clinical examination techniques were used to collect data. Before actual data collection commenced, three days training was given for data collectors followed by pre-test on 20 children 1-9 years old to identify active trachoma signs and symptoms. Five fifth year medical doctor students (MD) were recruited for data collection and children’s eye examination. Eye examination for each child was done by careful inspection of eyelashes cornea, limbus, eversion of the upper eyelids and inspection of the upper tarsal conjunctiva by the help of magnifying binocular lenses (x2.5) and penlight torches. Both eyes were examined in the same sequence and hygienic measures were also taken and results of the examination were registered. The guide used for diagnosis and reporting examination results with the simplified trachoma grading scheme was adapted from WHO [18].

Data Processing and Analysis

Data clean up and cross checking were done. Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 20 computer software was used to enter and analyze the data. Data were presented using a table. Percentages, mean and standard deviations were used to summarize descriptive data. Chi-square was calculated to determine the association between explanatory and outcome variable. A statistically significant association was declared when the p-value was less than 0.05.

Ethical Consideration

Support letter was obtained from Hawassa University, School of Public and Environmental Health. Shebedino District Health Office and Kebele administrative officials in the study area were informed about the study and then we obtained their verbal consents. Parent or Caregivers were entitled to provide consent on the behalf of children 1-9 years old. Hence, verbal consent was obtained from parent or caregiver after the brief description was given on the benefits, objectives, procedure, and risk of the study. Confidentiality and privacy of every respondent's information were ensured by not using any identifiers of the study participants. Children diagnosed with active trachoma were treated with azithromycin and referred to the nearby health facility for further treatments.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

In this study, a total of 173 children 1-9 years old and their parents or caregivers participated. Among the participated children, 92 (52.6%) were male and 81(47.4%) were female. Children’s age distribution showed that more than half 119 (68.2%) of children were within the age group 1 to 5 years. A mean age of the children was 4.29 ± 2.6 SD years (Table 1). More than half 118 (68.8 %) of children were living in households headed by men. Regarding occupation of household heads 53 (30.6%) was government employee followed by merchants 49 (28.3%). The household’s mean family size was 4.79 ± 1.48 SD persons. More than half of the respondents 91(52.6%) live in households with one to two rooms. Distribution of educational status among the head of households showed that 48 (27.7%) attended college and above, 34 (19.7%) attended secondary (7-17), 53 (30.6%) attended primary (1-6), and 38 (22%) were illiterate. Households which had two children age 1-9 years old were 111 (64.2%). Children from poor economic status households were 58 (33.5%) while from the medium were 82 (47.4%). From children whose age was between 6 to 9 years (n=55), majority 38 (69.1 %) of them were enrolled at the school for the academic year (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Active Trachoma | Total | χ2 (P-value) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes No (%) |

No No (%) |

No | % | ||

| Sex of household head  | 0.001 (0.971) | ||||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Male | 12 (7.5) | 106 (61.3) | 118 | 68.8 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Female | 7 (3.5) | 48 (27.7) | 55 | 31.2 | |

| Educational status of household head | 12.4 (0.006) | ||||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Illiterate | 8 (4.6) | 30 (17.3) | 38 | 22.0 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Primary (1-6) | 9 (5.2) | 44 (25.4) | 53 | 30.6 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Secondary (7-12) | 0 (0.0) | 34 (19.7) | 34 | 19.7 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â College and above | 2 (1.2) | 46 (26.6) | 48 | 27.7 | |

| Occupation status of household head | 7.8 (0.099) | ||||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Farmer | 5 (2.9) | 19 (11.0) | 24 | 13.9 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Craftsman | 4 (2.3) | 23 (13.3) | 27 | 15.6 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Merchant | 4 (2.3) | 45 (26.0) | 49 | 28.3 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Government employee | 2 (1.2) | 51 1(29.5) | 53 | 30.6 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Housewife | 4 (2.3) | 16 (9.2) | 20 | 11.6 | |

| Number of family member | 0.001 (0.997) | ||||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Less than five | 14 (8.1) | 111 (65.3) | 125 | 72.3 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Greater than five | 5 (2.9) | 43 (23.7) | 48 | 27.7 | |

| Number of children under 9 years | 1.153 (0.283) | ||||

| Less than two | 14 (8.1) | 97 (56.1) | 111 | 64.2 | |

| More than two | 5 (2.9) | 57 (33.9) | 62 | 35.8 | |

| Number of living room | 0.077 (0.782) | ||||

| Less than two | 11 (5.4) | 84 (48.6) | 95 | 54.9 | |

| More than two | 8 (4.6) | 70 (40.5) | 78 | 45.1 | |

| Age of the selected child | 0.49 (0.48) | ||||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 1-5 year | 14 (8.1) | 104 (60.1) | 118 | 68.2 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 6-9 year | 5 (2.9) | 50 (28.9) | 55 | 31.8 | |

| Sex of the selected child | 2.4 (0.123) | ||||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Male | 7 (4.0) | 85 (49.4) | 92 | 53 | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Female | 12 (7.0) | 68 (40) | 80 | 47 | |

| Economic status of household | 4.55 (0.033) | ||||

| Poor | 10 (5.6) | 48 (32.9) | 58 | 33.5 | |

| Medium | 8 (4.6) | 74 (43.8) | 82 | 47.4 | |

| High | 1(0.6) | 32 (18.5) | 33 | 19.1 | |

Table 1. Distribution of active trachoma among children 1-9 years old by socio-demographic characteristics in Leku town, Southern Ethiopia

The prevalence of active trachoma distribution varied across different socio-demographic variables. The prevalence was higher among female children, more than five household family size, households headed by illiterate or attended only primary education, poor or medium economic status of the household, and children between 1 and 5 years age group. However, in the bivariate analysis only educational status of the household head (χ2=12.4, p-value=0.006) and economic status of the household (χ2=4.55; p-value=0.033) showed significant association with the prevalence of active trachoma (Table 1).

Environmental and Behavioral Factors

More than two third 124 (71.7%) households of children, cooked their food in the kitchen, which is located outside the living room, while 49 (28%) households of children cooked their food in the same room in which the families live. Those children who live in households with cooking rooms have windows constitute 36.3% of total children. The common sources of water for domestic consumption in the study area were pipe water for 152 (87.9%) and protected well for 21 (12.1%) of the family. More than half of children (60.1%) live in households where the average daily water consumption is 20-40 L/family. Households dispose of their domestic solid wastes properly (by burning and burying) were 45.4% while 54.6% households dispose of their domestic solid wastes improperly (open field). All families of children had pit latrine. Households that had cattle were 75 (43.4%). Children, who shared the same rooms where the cattle are kept, were 5 (6.7%). Face washing practice and facial cleanness of the children were assessed by direct observation and self-response. More than half of the children 102 (59.0%) wash their faces once per day, while 71 (41.0%) wash their face twice and above per day. Most of children 118 (68.2%) didn’t use soap for face washing. Children’s facial cleanness observation revealed that 26 (15%) children had unclean face during the observation period (Table 2).

| Characteristic |        Active trachoma | Total  No (%) |

χ2 (P-value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes No (%) |

No No (%) |

|||

| Source of water | 0.94 (0.47) | |||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Pipe | 18 (10.4) | 134 (77.5) | 152 (87.9) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Protected well | 1 (0.6) | 20 (11.5) | 21 (12.1) | |

| Amount of water used per day | 2.47 (0.291) | |||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 20-40 L | 14 (8.1) | 90 (52) | 104 (60.1) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 60-80 L | 3 (1.7) | 51 (29.5) | 54 (31.2) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â >80 L | 2 (1.2) | 13 (7.5) | 15 (8.7) | |

| Place where food is cooked | 3.81 (0.05) | |||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â In the kitchen | 10 (5.8) | 114 (65.9) | 124 (71.7) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â In the living house | 9 (5.2) | 40 (22.8) | 49 (28 ) | |

| Cooking room has window | 0.27 (0.60) | |||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yes | 6 (3.5) | 58 (33.5) | 64 (37) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â No | 13 (7.5) | 96 (55.5) | 109 (63.7) | |

| Solid waste disposal | 1.17 (0.557) | |||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Burn | 7 (4) | 42 (24.3) | 49 (28.3) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Bury | 2 (1.2) | 28 (16.1) | 30 (17.3) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Open field | 10 (5.8) | 84 (48.5) | 94 (54.3) | |

| Cattle ownership | 0.14 (0.708) | |||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Yes | 9 (5.2) | 66 (38.2) | 75 (43.4) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â No | 10 (5.8) | 88 (50.8) | 98 (56.6) | |

| Place where cattle passing night (n=75) | 0.22 (0.89) | |||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â In the cattle house | 4 (5.3) | 33 (44) | 37 (49.3) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Living house but separately | 4 (5.3) | 4 (32) | 28 (37.3) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Same room with the family | 1 (1.3) | 9 (12.1) | 10 (13.4) | |

| Frequency of washing face | 0.79 (0.374) | |||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Once per day | 13 (7.5) | 89 (51.5) | 102 (59.0) | |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Two or more times per day | 6 (3.5) | 65 (47.5) | 71 (41.0) | |

| Face wash using soap | ||||

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Yes | 2 (1.2) | 53 (30.6) | 55 (31.8) | 5.28 (0.021) |

| Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â No | 17 (9.8) | 101 (58.4) | 118 (68.2) | |

| Children’s facial cleanness | ||||

| Clean | 1 (0.6) | 146 (84.4) | 147 (85) | 75.6 (0.00) |

| Not clean | 18 (10.4) | 8 (4.4) | 26 (15) | |

Table 2. Distribution of active trachoma among 1-9 years children by environmental factors in Leku town, Southern Ethiopia

The prevalence of active trachoma was higher among children from households daily estimated water consumption is 20-40 L and dispose of solid waste in open field. Furthermore, the prevalence was higher among children who washed their face once per a day, didn’t use soap during face washing and had an unclean face. Meanwhile, in the bivariate analysis only soap use for facial washing (χ2=5.28; p-value=0.021) and facial cleanness (χ2=75.6, p-value=0.000) had association with active trachoma (Table 2).

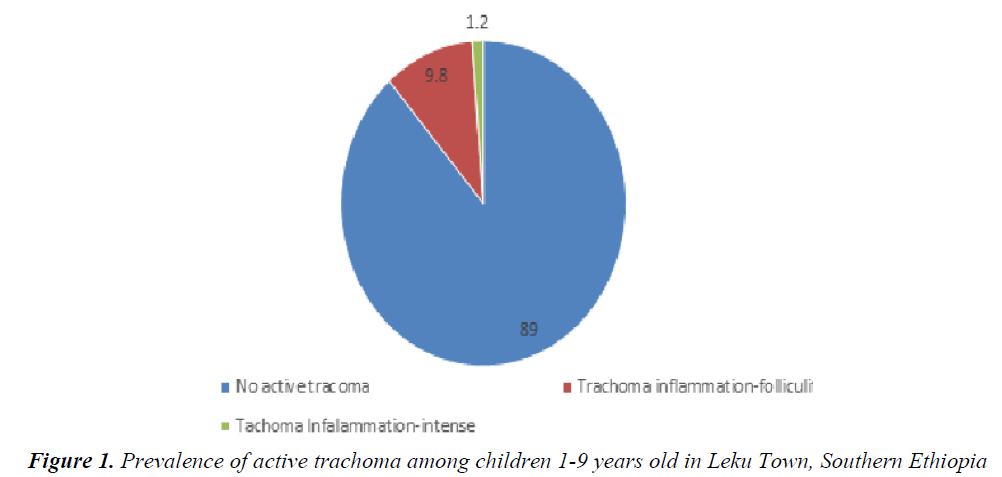

Prevalence of Active Trachoma

Enumerated children aged 1-9 years were examined for signs of trachoma. The signs of active trachoma (TF and TI) were observed in children 1-9 years of age regardless of gender. The overall prevalence of active trachoma among children aged 1-9 years was found to be 11.0% (TF 9.8% and TI1.2%) (Figure 1).

Discussion

The major objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of active trachoma among children aged 1-9 years in Leku town, Southern Ethiopia. Eye examination was carried out through inspection of eyelashes cornea, limbus, eversion of the upper eyelids and inspection of the upper tarsal conjunctiva by the help of penlight torches. Additionally, pre-tested structured questionnaire was used to gather socio-demographic, environmental and behavioral characteristics of the respondents.

This study revealed that prevalence of active trachoma among 1-9 years old children was 19 (11%). Of these, majority 17 (9.8%) had TF, and the rest 2 (1.2%) had TI which indicates the widespread distribution and severity of trachoma in the community. The prevalence of active trachoma (TF and TI) was low as compared to other studies conducted in Mojo and Lum district, Baso Liben District, Gonji Kolella district and Zala District of Ethiopia [8-11]. Also, the prevalence is low as compared to the prevalence of region-wide study conducted in SNNPR Ethiopia [12]. This is may be due to difference in geographic location. Unlike this study, other studies included children from a rural community where the active trachoma prevalence is high because of poor sanitation, poor access to health facilities and behavioral factors. However, the prevalence is higher than the prevalence of similar study conducted in Dera Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia [13,14]. Also, it is higher than the prevalence of other studies conducted abroad in Gambia and Sierra lion [15,16]. This is may be due to better access to safe water, improved sanitation and better access to health facilities in areas where these studies conducted.

In this study, distribution of active trachoma prevalence is high among children who are from household where the household head is illiterate or attended only primary education, family size is more than five, female children, age group 1 to 5 years, his/her household economic status is poor or medium as compared to their counterparts. Educational status of the household head and economic status of the household had significant association with prevalence of active trachoma. Similarly, in other studies conducted in Ethiopia these variables were identified as risk factors for active trachoma for children 1-9 years old [7,9,17]. This is because such variables limit a care provided to children and hinder utilization of health service. Also, affect the availability and access to safe water and basic sanitary facilities of the household.

Furthermore, this study showed high occurrence of active trachoma among children from households that utilize only 20-40 L of water for all domestic activities per day and dispose of solid waste in the open field. In addition, there is a higher occurrence of active trachoma among children whose face is washed once per day, have unclean face and soap is not being used during children face wash as compared to their counterparts. Meanwhile, in this study place where food cooked, soap use for children’s face wash and children’s unclean face showed significant association with prevalence of active trachoma. Similarly, other studies conducted in Ethiopia revealed similar significant association between prevalence of active trachoma and quantity of water consumed by household, open field solid waste disposal, soap use for children’s face wash and children’s unclean face [10,14,17]. Because, these factors facilitate transmission of trachoma through creating a conducive environment for flies to breed.

Conclusion

In this study, the prevalence of active trachoma is above WHOs’ cutoff point to commence mass antibiotic (azithromycin) distribution combined with measures to encourage facial cleanness and improve sanitation in the affected community. Factors such as education status of household head, economic status of household, soap use for children’s face wash and unclean face of the children showed significant association with prevalence of active trachoma. Because the sample size used in this study was small, we recommend further studies to be conducted using optimum sample size to compute more accurate population level prevalence and identify risk factors in the study area.

References

- Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Longo DL, et al. Harrison principles of internal medicine, 17th Edn. New York. McGraw-Hill Companies. 2008.

- http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs382/en/

- http://www.who.int/globalatlas

- FMOH. Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. Health Sector Transformation Plan (2015/2016 2019/2020). 2015.

- WHO. Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: First WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. World Health Organization 2010.

- Mariotti SP, Pascolini D, Nussbaumer RJ. Trachoma: global magnitude of a preventable cause of blindness. Br J Ophthalmol 2009; 93: 563-568.

- Berhane Y, Worku A, Bejiga A, et al. Prevalence of trachoma in Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev2007; 21.

- Yalew KN, Mekonnen MG, Jemaneh AA. Trachoma and its determinants in Mojo and Lume districts of Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J 2012; 13: 8.

- Ketema K, Tiruneh M, Woldeyohannes D, et al. Active trachoma and associated risk factors among children in Baso Liben District of East Gojjam, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 1105.

- Nigusie A, Berhe R, Gedefaw M. Prevalence and associated factors of active trachoma among children aged 1-9 years in rural communities of Gonji Kolella district, West Gojjam Zone, North West Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 2015; 8: 641.

- Mengistu K, Shegaze M, Woldemichael K, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with trachoma among children aged 1-9 years in Zala district, Gamo Gofa Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Clin Ophthalmol 2016; 10: 1663-1670.

- Haileselassie TA, Macleod C, Endriyas M, et al, Prevalence of and risk factors for trachoma in southern nations, nationalities and peoples? region, Ethiopia: Results of 40 population-based prevalence surveys carried out with the global trachoma mapping project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2016; 23: 84-93.

- Gedefaw M, ShiferawA, AlamrewZ, et al. Current state of active trachoma among elementary school students in the context of ambitious national growth plan: The case of Ethiopia. Health 2013; 5; 1768-1773.

- Alemayehu M, Koye DN, Tariku A, et al. Prevalence of active trachoma and its associated factors among rural and urban children in Dera Woreda, north-west Ethiopia: A comparative cross-sectional study. BioMed Res Int 2015: 8.

- Quicke E, Sillah A, Harding-Esch EM, et al. Follicular trachoma and trichiasis prevalence in an urban community in the Gambia, West Africa: Is there a need to include urbanareas in national trachoma surveillance? Trop Med Int Health 2013; 18: 1344-1352.

- Koroma JB, Heck E, Vandy M, et al. The epidemiology of trachoma in the five northern districts of Sierra Leone. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2011; 18: 150-157.

- Mesfin MM, de la Camera J, Tareke IG, et al. A community-based trachoma survey: Prevalence and risk factors in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2006; 13:173-181.

- World Health Organization: Primary health care level management of trachoma. Geneva: WHO; [WHO/PBL/93.33] 1993.