Research Article - Current Pediatric Research (2024) Volume 28, Issue 7

Palatal mucormycosis in an immune-competent infant following dengue haemorrhagic fever: A rare disease entity, treated with a challenging course of IV liposomal amphotericin B for 270+ days, longest duration reported from Sri Lanka.

Hashan Pathiraja1,2*, Rakitha Munasighe1, Rasika Gunapala1, Jerrad Fernando1, Sandini Gunaratne1, Chethana Pemasiri3, Primali Jayasekera3

1Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children, Colombo, Sri Lanka

2Department of Paediatrics, University of Kelaniya, Ragama, Sri Lank

3Department of Mycology, Medical Research Institute, Colombo, Sri Lanka

- Corresponding Author:

- Hashan Pathiraja

Department of Paediatrics, University of Kelaniya, Ragama, Sri Lanka

E-mail: hashanpathiraja@gmail.com

Received: 25 June, 2024, Manuscript No. AAJCP-24-142625; Editor assigned: 27 June, 2024, Pre QC No. AAJCP-24-142625 (PQ); Reviewed: 12 July, 2024, QC No. AAJCP-24-142625; Revised: 19 July, 2024, Manuscript No. AAJCP-24-142625 (R); Published: 26 July, 2024, DOI:10.35841/0971-9032.28.07.2302-2306.

Abstract

Background: Mucormycosis is an emerging global illness with significant morbidity and mortality. Causative fungi can spread through inhalation of sporangiospores or direct inoculation through damaged skin or mucosa in susceptible patients, especially those with impaired immune systems. Here we report a rare occurrence of the disease in an immunocompetent infant following dengue haemorrhagic fever, highlighting the treatment course which is the longest duration reported from Sri Lanka so far.

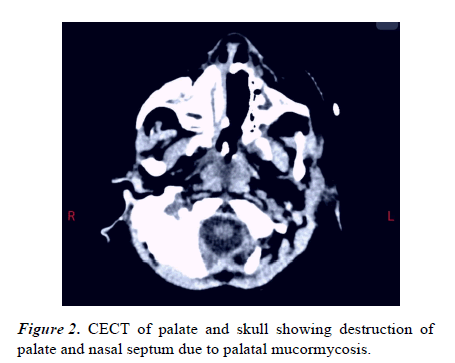

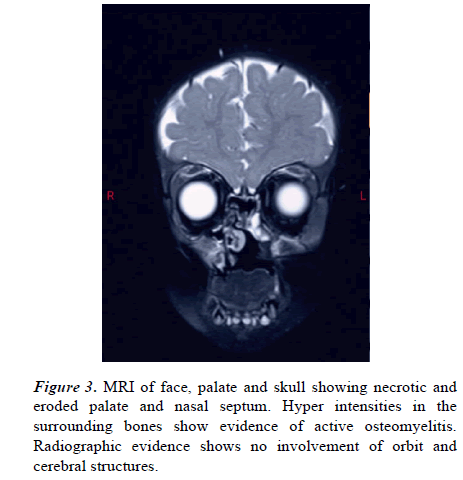

Case presentation: A 4-month-old infant was admitted to the medical Intensive Care Unit (ICU) after experiencing dengue haemorrhagic fever, which was complicated by multi-organ dysfunction and required intubation. After recovery, he was found to have a necrotic lesion in the palate, which was confirmed to be mucormycosis following biopsy. Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans showed erosions of the hard palate and involvement of the paranasal sinuses, orbital floor and soft palate without brain or eye lesions.

The child was started on Intravenous (IV) liposomal amphotericin B and required several debridement surgeries. Radiological studies showed persistent active bone lesions and antifungals were continued until radiological, mycological and clinical clearance was achieved. Intravenous amphotericin B was given for 270+ days required central lines and was complicated by venous thrombosis.

A palatal prosthesis was inserted until a definite palatal repair is done. The child is clinically well and thriving. Laboratory evaluations showed normal IgG and subclasses, IgA, IgM, and IgE levels, HIV testing was negative, Nitroblue Tetrazolium Test (NBT) was normal and metabolic screening was negative.

Conclusion: Though mucormycosis usually occur in children with immunosuppression or metabolic syndromes, it can occur in immunocompetent children, especially following a critical illness with high lactic acid levels, as in our case. It’s important to manage these children under multi-disciplinary care and complete treatment until there is evidence of radiological clearance to achieve better outcome.

Keywords

Mucormycosis, Necrosis, Hard palate, Liposomal amphotericin B.

Introduction

Palatal mucormycosis is a rare but serious and emerging fungal infection caused by various species of fungi belonging to the order Mucorales, most commonly Rhizopus species and less commonly Mucor, Rhizomucor, and Absidia species [1-3].

While it predominantly affects adults with underlying medical conditions such as uncontrolled diabetes, immunocompromised states or those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, it can also occur in children, albeit less frequently [4-6].

The predisposing factors for mucormycosis in children are often similar to those in adults, such as uncontrolled diabetes, immunocompromised states (including chemotherapy, hematological malignancies, solid organ transplantation or congenital immunodeficiency), prolonged corticosteroid use, malnutrition or invasive medical interventions like insertion of nasogastric or endotracheal tubes [5-8]. Between 9%-36% of cases occur in individuals with diabetes. Prematurity remains a major risk factor for neonatal disease. In around 9.5% of paediatric cases, no predisposing risk factor has been identified.

Early diagnosis and prompt initiation of treatment are important for improving outcomes in children with palatal mucormycosis. Diagnosis is made through the microscopic identification of the fungal hyphae in the tissue biopsy [9-11]. Treatment typically involves a combination of surgical debridement to remove infected tissue and antifungal therapy often with amphotericin B, which is the primary agent used to combat mucormycosis [12-15].

In this report we present an infant with palatal mucormycosis with no underlying immunodeficiency and metabolic disease who went on to receive the longest duration of IV amphotericin B reported so far in Sri Lanka.

Case Presentation

We report a Sri Lankan Muslim male infant who was referred and transferred to a medical unit after noting a blackish necrotic patch on the palate. This is the only child born to healthy, non-consanguineous parents with an uneventful antenatal period. A child was born at term with a birth weight of 2.6 kg. There is no family history of early infantile deaths. At 4 months of age, the child had a febrile illness and was diagnosed to have dengue haemorrhagic fever.

The course of the disease got complicated, and the child went to dengue shock syndrome and was transferred to medical intensive care unit. Despite optimum management, the child developed multi-organ failure with acute kidney and liver injuries, along with tissue hypoxia leading to elevated lactate levels. He was intubated for 5 days. After extubating, he was noted to have a black, necrotic, foul-smelling patch on the palate on day 8 of his total illness and continued to have fever.

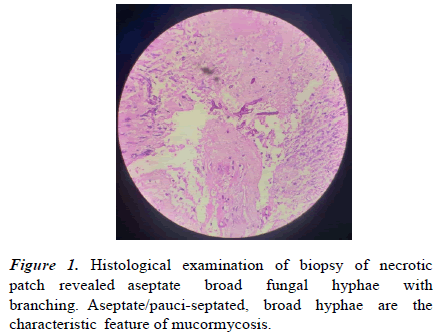

Once hemodynamically stable, he was transferred to the medical ward for further care and evaluation. The child received intravenous piperacillin, tazobactam, and flucloxacillin. Then he was given a 14 day course of IV meropenem and metronidazole with 7 days of IV fluconazole. Despite the resolution of the fever, the palatal necrotic patch persisted along with the foul smell. He was referred to both the Ear Nose Throat (ENT) and Oro Maxilo Facial (OMF) teams. Histological examination of necrotic patch revealed aseptate broad fungal hyphae with branching, and diagnosis of palatal mucormycosis was made (Figure 1). Although similar fungal hyphae were seen in KOH mount of the biopsy specimen, the infecting organism could not be recovered by culture.

His lowest haemoglobin during acute illness was 7.2 g/dl, and he received a blood transfusion. The mean haemoglobin thereafter was 9.8 g/dl. The mean total white cell count was 10.1 cells/mm3, with 65% neutrophils. The mean platelet count was 212 mm3. The highest CRP and ESR were 58 and 30, respectively. He had elevated blood lactate levels, highest at 4.4 mmol/L. His blood culture was initially positive for Streptomonas bacteria. No fungal growth was produced. His liver and renal functions were normalized after recovering from multi-organ failure. Immunological investigations, including flow cytometry, immunoglobulin levels and the NBT test were negative for any immunodeficiency. HIV and hepatitis B/C screenings were negative. Metabolic screening did not suggest any metabolic disease and blood sugar levels were normal.

After the histological diagnosis, the child was initiated on IV liposomal amphotericin B with the liaison of the mycology team. At the time of the tissue biopsy, debridement of the necrotic tissue was done. Necrosis was noted up to the left greater and lesser palatal vessels and loss of bone tissue, resulting in the loss of medial incisor teeth. Excision of mobile teeth under general anaesthesia was performed.

At 3 weeks of amphotericin treatment, the first imaging was done. The Contrast-Enhanced Computer Tomography (CECT palate showed bone changes suggestive of osteomyelitis (Figure 2). There was no abscess formation. The Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI brain at 4 weeks of treatment did not show any involvement of the brain or orbits (Figure 3). However, pan-sinusitis with bilateral mastoiditis was noted. A multi-disciplinary team decision was made to continue IV amphotericin B until clinical, mycological and radiological evidence of bone cure is achieved. Repeat imaging was done at 2 months and 3 months of treatment, both showing bone erosion with interval progression. At 5 months of treatment (day 156 of IV amphotericin, wound exploration was done under general anaesthesia. There was no clinical evidence of active bone lesions, and biopsy specimens did not show any fungal hyphae.

However, IV amphotericin B was given for a total of 275 days, as repeated CECT and MRIs of the head and neck showed active bone lesions. Treatment was stopped after the last imaging showed no active lesions and oral posaconazole was given for another 3 months. The course of IV amphotericin B was challenging as it was given through central lines and peripherally inserted central lines, which were complicated with thrombus formation and abscess formation. Serum creatinine was regularly monitored and was within normal limits. However, a successful, prolonged course was completed with the complete recovery of the child. Five months after completion of antifungal therapy, the child is thriving well and remains asymptomatic. Prosthesis was inserted into the palatal defect and palatal closure is planned in due course by the plastic surgery team.

Results and Discussion

Invasive mucormycosis has significant morbidity and mortality, especially among immunosuppressed children [1,2]. Mucormycosis cases are grouped into six main clinical entities: Rhino Cerebral (ROCM, pulmonary, cutaneous gastrointestinal, disseminated and unusual presentations. Rhino cerebral disease can later spread to the hard palate and other facial structures and it is the most common and serious entity. ROCM will gradually involve the nasal septum, epithelium, cavernous sinus, orbit, and brain. Hence, it is associated with high morbidity and mortality [3]. Palatal mucormycosis, on the other hand, has less morbidity and mortality. However, it’s very rare for palatal mucormycosis to occur in isolation. Most of the time, it spreads to involve the surrounding structures and, later, the orbit and brain as well [4]. We believe that the prompt and prolonged course of IV amphotericin B must have prevented the progression of disease in our patient, thereby minimizing the morbidity.

The predisposing factors for mucormycosis in children are often similar to those in adults, such as uncontrolled diabetes, immunocompromised states, prolonged corticosteroid use, malnutrition, or invasive medical interventions like the insertion of nasogastric or endotracheal tubes [5,6]. The evaluation of our patient suggested that he is immunecompetent and there is no evidence of metabolic disease. However, multi-organ failure and skin breach due to endotracheal intubation must have resulted in acquiring the disease. High blood lactate levels are thought to be a risk factor for mucormycosis. Our patient exhibited elevated lactate levels as high as 4.4 mmol/L due to tissue hypoxia following multiorgan failure in dengue haemorrhagic fever. This highlights the fact that such rare but serious infections can occur even in otherwise healthy children after a critical illness [7].

There will be visible palatal mucosal darkening or swelling prior to the rapid development of necrosis and ulceration in palatal mucormycosis [2]. Similar onsets have also been reported in cases of rhino-orbital mucormycosis affecting the palate first. Since these are angio-invasive fungi, they have a predisposition to cause thrombosis which will lead to necrosis of tissue [8].

A similar lesion was detected in our patient as well, which led to the diagnosis of this condition. Hence, frequent monitoring of the mucous membranes in the oral cavity by the health care staff is important among children receiving critical care to identify the disease at an early stage. Oral and dental hygiene are important aspects of critical care.

Causative organisms of mucormycosis are ubiquitous fungi, which can be commonly detected in the environment, particularly in decaying organic matter [1,2]. Given their widespread occurrence, it is essential to recognize the potential risks associated with these agents, particularly for individuals with weakened immune systems. In tissue, Mucorales hyphae can often be distinguished from other common molds by their broad (3-25 μm diameter), thin walled, mostly aseptate hyphae. These hyphae have focal bulbous dilatation and nondichotomous branching at occasional right angles [9]. Identification of Mucorales to genus and species level requires cultivation of the fungus in a suitable culture medium to examine their morphological structures [10]. Unfortunately, culture recovery of Mucorales from tissue is inherently poor owing to the friability of the non-septate hyphae, making them more susceptible to damage during tissue manipulation [9-11]. This may be the reason why our biopsy specimen did not yield a growth of the infecting fungus.

Surgical debridement is an important aspect of management for both histological diagnosis and clearing the infected tissues. Because of the surrounding delicate structures, the depth of the infection, and the difficulty in assessing the involved areas, surgical intervention may be difficult. Most of the time, radical surgical debridement is necessary to get a cure combined with medical treatment [12]. Most children will require multiple surgeries. It is important to involve multiple surgical disciplines as the infection involves the head and neck region. The surgical debridement of our patient was done as a team effort from the ear-nose-throat surgery, plastic and reconstructive surgery, and Oro-Maxillary-Facial surgery disciplines. Surgical input is later important in palatal reconstruction once the bone healing has completed [13]. Our patient is also scheduled for palatal reconstruction in due course.

Mucorales are inherently resistant to many antifungal drugs used to treat systemic mycoses. Amphotericin B is active against most agents of mucormycosis with MIC90 of 1 μg/ml. Posaconazole is the only currently available triazole with activity against several agents of mucormycosis with minimal inhibitory concentration 90-0.25 μg/ml (14-15). In this patient IV liposomal amphotericin B was initiated at 3 mg/kg/day dose and later increased to 5 mg/kg/day due to inadequate response [16-18].

Conclusion

The duration of treatment for mucormycosis is highly individualized. The key deciding factors of the duration are near normalization of radiographic imaging, negative biopsy specimen and cultures from the affected side and recovery from immune suppression. It was important to continue IV amphotericin B until radiological evidence of clearance was achieved. Despite being a challenging course, we were able to continue treatment for our patient, which ended up being the longest duration of treatment for mucormycosis in both adult and child populations in Sri Lanka. Here we have reported a rare case of isolated palatal mucormycosis in an immunecompetent child who was successfully treated. As authors, we like to highlight the possibility of such rare clinical entities in children after critical illnesses.

Author’s Declaration

Consent to publish declaration

Informed written consent was obtained from the parents of the child to publish the information and accompanying images pertaining to child’s illness.

Data availability statements

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Contributions

HP, RM, RG, JF, SG, CP and PJ contributed with the diagnosis and management of the patient. HP, CP and PJ prepared the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Al-Ghabra Y, Hamdi M, Alkheder A, et al. Palatal mucormycosis in a 2-month-old child: A very rare case report and a literature review. Med Mycol Case Rep 2024;43:100628.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54(Suppl-1):S23–S34.

- Serris A, Danion F, Lanternier F. Disease entities in mucormycosis. J Fungi (Basel) 2019;5(1).

- Sorour A, Abdelrahman AS, Abdelkareem A, et al. Rhino-orbito-cerebral mucormycosis infection in a 4-year-old Egyptian girl. Med Mycol Case Rep 2022;37:29–32.

- Kennedy KJ, Daveson K, Slavin MA, et al. Mucormycosis in Australia: Contemporary epidemiology and outcomes. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016;22(9):775–781.

- Francis Joshua R, Paola V, Penelope B, et al. Mucormycosis in children: Review and recommendations for management. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2018;7(2):159–164.

- Sharma A, Goel A. Mucormycosis: Risk factors, diagnosis, treatments, and challenges during COVID-19 pandemic. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2022;67(3):363-387.

- Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, et al. Pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54(Suppl 1):S16–S22. Suppl 1.

- Skiada A, Pavleas I, Drogari-Apiranthitou M. Epidemiology and diagnosis of mucormycosis: an update. J Fungi (Basel) 2020;6(4):265.

- Cornely OA, Arikan-Akdagli S, Dannaoui E, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis 2013. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20(Suppl 3):5–26.

- Lackner N, Posch W, Lass-Florl C. Microbiological and molecular diagnosis of mucormycosis: From old to new. Microorganisms 2021;9(7):1518.

- Augustine HFM, White C, Bain J. Aggressive combined medical and surgical management of mucormycosis results in disease eradication in 2 pediatric patients. Plast Surg (Oakv) 2017;25(3):211–217.

- Kalaskar RR, Kalaskar AR, Ganvir S. Oral mucormycosis in an 18-month-old child: A rare case report with a literature review. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;42(2):105–110.

- Rai S, Misra D, Misra A, et al. Palatal mucormycosis masquerading as bacterial and fungal osteomyelitis: A rare case report. Contemp Clin Dent 2018;9(2):309-313.

- Laniado-Laborín R, Cabrales-Vargas MN. Amphotericin B: Side effects and toxicity. Rev Iberoam Micol 2009;26(4):223–7.

- Mengji AK, Yaga US, Gollamudi N, et al. Mucormycosis in a surgical defect masquerading as osteomyelitis: A case report and review of literature. Pan Afr Med J 2016;23:16.

- Samaranayake LP, Cheung LK, Samaranayake YH. Candidiasis and other fungal diseases of the mouth. Dermatol Ther 2002;15:252–70.

- Belaval V. Rhino-orbital mucormycosis. Radiopaedia 2024.