Research Article - Biomedical Research (2017) Volume 28, Issue 10

Neurophobia: a myth or an unpleasant fact for primary care physicians

Ozlem Midik1, Bektas Murat Yalcin2, Esra Yalcin3 and Onur Ozturk4*

1Department of Medical Education, Ondokuz Mayis University Faculty of Medicine, Samsun, Turkey

2Department of Family Practice, Ondokuz Mayis University Faculty of Medicine, Samsun, Turkey

3Clinic of Neurology, Gazi State Hospital, Samsun, Turkey

4Asarcik Meydan Family Healthcare Center, Samsun, Turkey

- *Corresponding Author:

- Onur Ozturk

Asarcik Meydan Family Healthcare Center, Samsun, Turkey

Accepted date: March 06, 2017

Abstract

We aimed to investigate neurophobia among primary care physicians. This study is designed as a descriptive and analytic research. At the 5th-7th meetings of the Family Practice Academy Research Days, volunteered 425 primary care physicians participated in this study. They had answered a questionnaire investigating the participants' interest, knowledge, professional confidence and perceived hardness of neurology by comparing it with other 10 speciality. They replied about the frequency, knowledge, professional confidence and referral rate of several neurological problems/diseases they encounter while practicing in primary care. Lastly they stated their opinions about possible reasons for perceived hardness in neurology with possible solution methods which might help them improving their neurology knowledge and skills. The participant's knowledge level (F=12.063, p<0.001), personal interest (F=8.795, p<0.001) and professional confidence (F=9.245, p<0.001) were lower than cardiology, dermatology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, nephrology, respiratory and rheumatology compared with neurology. They also perceive it harder compared to these specialities (F=10,214, p<0,001). The expectations were oncology and haematology. Need to know neurophysiology/anatomy, complexity of neurology and the rareness of the opportunity to work with a neurologist is the most common reasons for neurophobia. Headache was the most common problem that they encountered (F=8,512, p<0,001), while they have got the highest knowledge level (F=6,474, p<0,001), professional confidence to manage it (F=3,214, p<0,001) and had lowest referral rate (F=9,521, p<0,001). As conclusion, neurophobia is present inexperienced primary care physicians. Our results must be confirmed and interventional studies are needed to eliminate this condition in primary care.

Keywords

Primary Care, Neurology, Medical education, Neurophobia.

Introduction

Primary care physicians, who are the first point of contact for most patients with neurological disorders, take on several responsibilities in the initial diagnosis and management of a broad range of problems affecting the nervous system [1]. It has been estimated that 20% of patients applying to primary care physicians have neurological complaints and 9% of the daily workload of a primary care physician is devoted to the evaluation and management of diseases of the nervous system [2-4]. However, family physicians might feel uncomfortable and dislike dealing with neurological problems and disorders [5]. Primary care physicians consider their neurology knowledge less satisfactory compared to the subjects related to other systems [6]. They also perceive neurology more difficult than other specialties [6]. The frequency and severity of this problem are higher than expected [7]. In 1994, Jozefowicz [8] coined the term 'neurophobia' for this phenomenon. According to Jozefowicz, neurophobia is "fear of the neural sciences and clinical neurology that is due to the students' inability to apply their knowledge of basic sciences to clinical situations." Neurophobia may range from disliking patients with neurological problems to avoiding clinical management of these patients and dismissing them as quickly as possible [9]. In severe situations, physicians report paralysis of thinking or inability to take action in patients with neurological problems due to the loss of self-confidence [10,11]. Neurophobia and missing information can lead to misdiagnosis.

To investigate neurophobia among primary care physicians in Turkey, we designed a study based on the four aspects of Kern's approach to curriculum development (problem identification, needs assessment for targeted learners, instructional strategies, and evaluation/feedback) [12]. We prepared a questionnaire to compare the primary care physicians’ attitudes and beliefs towards patients with neurological disorders and those with diseases of other internal specialties. We investigated the frequency of several neurological problems/diseases they encounter, their professional confidence in managing these patients, and the referral rate. Lastly, we examined the reasons for neurophobia (if present) in family physicians and their recommendations that could help to overcome this problem.

Patients and Methods

Study design

This study was designed as a descriptive and analytic research. The research was conducted at the 5th, 6th and 7th the Family Practice Academy Research Days, which was held in different cities of Turkey (Canakkale, Ankara, and Hatay) from May 2014 to April 2015 with six months interval. In these meetings, primary care physicians from all parts of the country met for scientific activities. The primary care physicians attending the meetings were informed about the aim of this study and provided with the questionnaire. A total of 425 primary care physicians participated in the study (response rate 82.5%). The questionnaire was based on the recent literature on this topic [5-17].

The questionnaire

The questionnaire started with investigating demographic and professional features of the participants. In the first part of the questionnaire, the participants' interests, knowledge, professional confidence and perceived hardness in neurology compared to other ten specialties (cardiology, dermatology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, nephrology, neurology, respiratory, rheumatology, hematology, and oncology) were investigated. Each item in the questionnaire was evaluated with a 5-point Likert scale (1=very low, 5=very much). In the second part, we questioned their knowledge and professional confidence related to different neurological problems/diseases. Besides, the frequency of patients with neurological disorder and referral rate in these patients were also inquired in this section. These items were evaluated with a 5-point Likert scale (1=very few, 5=very frequent). In the last part, the participants stated their opinions on possible reasons for perceived hardness in neurology and which learning method might help them improving their neurology knowledge and skills. These items were evaluated with a 5-point Likert scale (1=unimportant, 5=very important).

Statistical analysis

We used SSPS version 15.0 to analyze the data. A p value of < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant. The averages of each item (knowledge, interest, professional confidence and perceived hardness) were calculated using scores obtained from the 5-point Likert scale, and they were accepted as dependent variables. In different items, the statistical relationship between two specialties was investigated with paired samples t-test. To investigate the relationship between these specialties and neurology in different items, we used repeated measures analyses with a post-hoc Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. The knowledge, professional confidence, frequency, and referral rates of several diseases/ problems that primary care physicians encounter were also analyzed with repeated measures analyses with a post-hoc Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. The mod, median and skewness were also calculated, where needed. Cronbach's alpha was used to verify reliability in each item sets.

Ethical issues

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ondokuz May?s University.

Results

A total of 425 primary care physician participated in the study. There were 250 (58.6%) females and 175 (41.4%) males. They have been working as a primary care physician for 7.71 ± 6.41 years. There was a significant difference between the male (10.11 ± 6.59 years) and female (5.98 ± 5.74 years) practitioners in terms of the years of practice as a primary care physician (t=3.093, p=0.003).

Knowledge, interest, difficulty and confidence

The mean of the Likert scores in knowledge, personal interest, perceived difficulty and professional confidence in different specialties, and their comparison with neurology were presented in Table 1. The repeated measures analyses comparing neurology with other specialties in terms of knowledge, interest, confidence and perceived hardness were shown in Table 2. These results indicate that primary care physicians’ knowledge level, personal interest, and professional confidence in neurology were lower than cardiology, dermatology, endocrinology, gastroenterology, nephrology, respiratory and rheumatology. They also perceive neurology harder than these specialties. Primary care physicians' knowledge level, personal interest, professional confidence and perceived hardness were similar with hematology. The oncology scores for knowledge level, personal interest, and professional confidence were lower than neurology while they perceive oncology harder than all of the compared specialties including hematology and neurology. The internal reliability analyses revealed Cronbach alpha value for knowledge 0.87 (Item-total correlation was between 0.321-0.608), personal interest for 0.83 (Item-total correlation was between 0.402-0.612), perceived difficulty for 0.84 (Itemtotal correlation between 0.472-0.618), and professional confidence for 0.88 (Item-total correlation between 0.271-0.510).

| Medical Specialities | Knowledge (1=none, 5=Very Indeed) |

t* p |

Personal interest (1=none, 5=Very Indeed) |

t* p |

Professional Confidence (1=none, 5=Very Indeed) |

t* p |

Percieved hardness (1=none, 5=Very Indeed) |

t* p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurology | 2.79 ± 0.7 | 2,83 ± 0,8 | 2,80 ± 0,9 | 3.80 ± 0.9 | ||||

| Cardiology | 3.65 ± 1.0 | 3.254 <0.001 |

3,23 ± 1,0 | 3,868 <0,001 |

3,26 ± 0,8 | 4,685 <0,001 |

3.95 ± 0,8 | 3,366 <0,001 |

| Dermatology | 3.1 ± 1.7 | 4.215 <0.001 |

3.31 ± 1.1 | 3.393 <0.001 |

3,43 ± 0,8 | 5,203 <0,001 |

2.38 ± 0.8 | 12.766 <0.001 |

| Endocrinology | 3.38 ± 1.5 | 4.874 <0,001 |

3.54 ± 1.0 | 6.170 <0.001 |

3.40 ± 0.7 | 5.875 <0.001 |

3.29 ± 0.7 | 5.075 <0.001 |

| Gastroentrology | 3.56 ± 0.9 | 6.058 <0.001 |

3.39 ± 1.0 | 5.041 <0.001 |

3.60 ± 0.8 | 7.301 <0.001 |

3.11 ± 0.8 | 7.099 =0.036 |

| Nephrology | 3.08 ± 1.1 | 2.098 =0.015 |

3.02 ± 0.9 | 2.872 =0.02 |

3.01 ± 0.9 | 2.195 =0.0018 |

3.61 ± 0.9 | 2.025 <0.001 |

| Respiratory | 3.48 ± 1.0 | 4.231 <0.001 |

3.23 ± 0.9 | 3.776 <0.001 |

3.55 ± 0.8 | 7.118 <0.001 |

3.01 ± 0.8 | 7.960 <0.001 |

| Rheumatology | 3.11 ± 0.9 | 1.542 =0.002 |

3.05 ± 1.1 | 1.207 =0.009 |

3.12 ± 0.9 | 3.043 =0.003 |

3.02 ± 0.9 | 6.309 <0.001 |

| Hemeatology | 2.98 ± 0.7 | -0.786 =0.258 |

2.91 ± 1.0 | -0.398 =0.692 |

2.97 ± 0.9 | -0.568 =0.572 |

3.85 ± 0.9 | -0.398 =0.692 |

| Oncology | 2.68 ± 1.1 | 6.821 <0.001 |

2.43 ± 1.03 | 4.135 <0.001 |

2.29 ± 1.0 | 5.368 <0.001 |

4.16 ± 0.9 | 2.887 =0.005 |

Table 1: The mean scores of the Likeert and comparison of the neurology to each of the other medical specialities of knowledge level, personal interest, professional confidence and perceived hardness.

| Medical Specialities | Knowledge Sig. (p) |

95% CI * (Lower and Upper Bound) |

Personal interest Sig. (p) |

95% CI * (Lower and Upper Bound) |

Professional Confidence Sig. (p) |

95% CI * (Lower and Upper Bound) |

Percieved hardness Sig. (p) |

95% CI * (Lower and Upper Bound) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiology | 0.0001 | -0.963-0.186 | 0.009 | -0.771-0.053 | 0.001 | -0.484 0.205 |

0.006 | -0.675 0.025 |

| Dermatology | 0.0001 | -1.254-0.309 | 0.008 | -0.918-0.024 | 0.0001 | 1.038 1.799 |

0.024 | -0.896-0.029 |

| Endocrinology | 0.0001 | -1.318-0.567 | 0.001 | -1.123-0.336 | 0.0001 | 0.176 0.871 |

0.0001 | -0.851-0.149 |

| Gastroentrology | 0.0001 | -1.658-0.779 | 0.001 | -0.923-0160 | 0.0001 | 0.354 1.018 |

0.0001 | -1.022-0.228 |

| Nephrology | 0.001 | -0.792-0.105 | 0.01 | -0.923-0.160 | 0.001 | -0.117 0.535 |

0.0023 | -0.335 0.260 |

| Respiratory | 0.0001 | -1.579-0.720 | 0.026 | -0.413-0.296 | 0.0001 | 0.463 1.141 |

0.0001 | -0.930-0.170 |

| Rheumatology | 0.0001 | -1.118-0.261 | 0.015 | -0.755-0.022 | 0.0001 | 0.356 1.202 |

0.04 | -0.626 0.076 |

| Hemeatology | 0.411 | -0.957-0.009 | 0.326 | -0.615-0.262 | 0.235 | -0.441 0.348 |

0.435 | -0.460 0.285 |

| Oncology | 0.004 | -0.290-0.589 | 0.002 | -0.350-.468 | 0.012 | -0.782 0.061 |

0.005 | 0.070 0.780 |

Table 2: The repeated measures test comparing difference between neurology versus other specialities in terms of knowledge, interest, confidence and perceived hardness.

The factors related to perceived difficulty with neurology

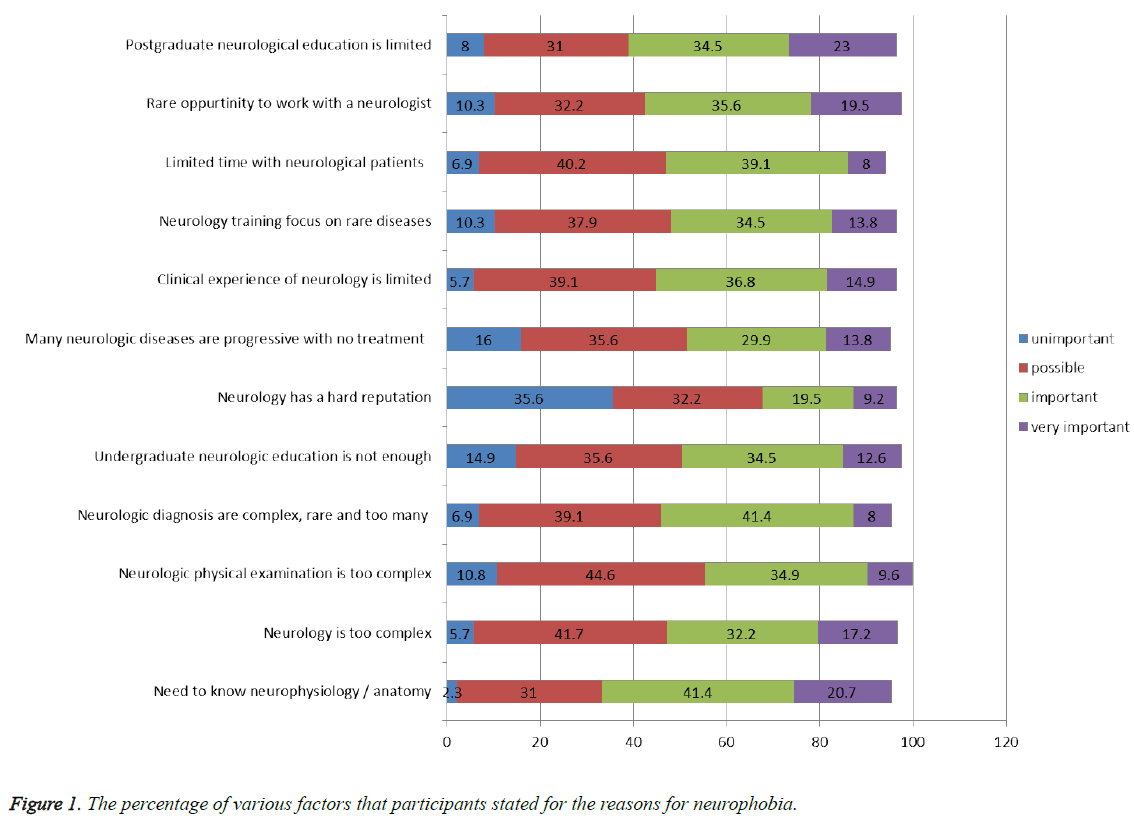

The mean scores of the various factors related to perceived hardness in neurology were presented in Figure 1. More than 50% of the participants identified the need to know neurophysiology/anatomy, the complexity of neurology, and the rareness of the opportunity to work with a neurologist as important or very important factors. The Cronbach’s alpha value for these set of questions was 0.88 (Item-total correlation was between 0.351-0.658).

The neurological problems/diseases workload of primary care physicians

The most common neurological problems/diseases encountered by primary care physicians, their knowledge related to neurological disorders, their professional confidence in the management of these disorders and their referral rate to secondary or tertiary health care were presented in Table 3. In this table, the statistical relationship between each of the neurological disease/problem's means of four items (frequency, knowledge, confidence and referral rate) were presented. Compared to others, headache was the most common neurologic problem encountered by primary care physicians (F=8.512, p<0.001). While they had the highest knowledge level (F=6.474, p<0.001) and professional confidence (F=3.214, p<0.001) in managing headache, the referral rate was lowest for headache (F=9.521, p<0.001). Many diseases/ problems had higher referral rates than expected (vertigo, neuropathies, and epilepsy, etc). The scores of four items were statistically different in headache, epilepsy, cerebrovascular diseases, neuropathies, vertebral disorders, neurological infections, Alzheimer diseases, vertigo and sleep disorders.

| The neurological problems/diseases |

Frequency† | Knowledge* | Confidence | Referral rate** | Repeated Measurement Analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headache | 4.25 ± 0.6# | 4.01 ± 0.1# | 3.85 ± 0.6 | 2.52 ± 1.0# | F=8.564 p<0.001 |

| Epilepsy | 3.11 ± 0.8 | 3.02 ± 0.7# | 3.01 ± 0.8# | 4.33 ± 0.8# | F=2.814 p=0.02 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.91 ± 1.0 | 2.11 ± 0.2# | 2.05 ± 0.8# | 4.23 ± 0.8# | F=6.584 P<0.001 |

| Neuropathies | 2.71 ± 0.8# | 2.61 ± 0.2# | 2.91 ± 0.9 | 4.29 ± 0.9# | F=9.214 P<0.001 |

| Vertebral disorders | 2.45 ± 0.9# | 2.81 ± 0.1 | 3.02 ± 0.8 | 4.17 ± 0.7# | F=5.412 p<0.001 |

| Neuroinfections | 1.02 ± 0.9# | 2.41 ± 0.2 | 2.36 ± 0.9 | 4.29 ± 0.8# | F=9.012 p<0.001 |

| Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia | 2.01 ± 0.7# | 2.65 ± 0.6 | 2.85 ± 0.8 | 4.06 ± 0.9# | F=3.015 p<0.01 |

| Parkinson disease | 2.21 ± 0.9 | 2.58 ± 0.5 | 3.11 ± 0.7 | 3.87 ± 0.9 | F=1.015 p=0.324 |

| Dizziness | 3.21 ± 0.8 | 3.02 ± 0.7 | 3.54 ± 0.6 | 2.84 ± 1.0 | F=0.987 p=0.298 |

| Vertigo | 2.45 ± 0.9# | 2.91 ± 0.1 | 3.02 ± 0.8 | 4.17 ± 0.7# | F=8.742 p<0.001 |

| Sleep disturbances | 2.32 ± 0.7# | 2.71 ± 0.8 | 2.87 ± 0.9 | 3.89 ± 0.9# | F=2.235 P=0.01 |

*The essantial knowledge about the disease (1=very little, 5=very much indeed)

?Professianal confidence to manage that problem/disease (1=None, 5=Full )

**How often do you need to refere this problem / disease? (1=Never, 5=Always)

#The statistical significancy caused between the means of each item within each disease/problem

Table 3: The mean frequency, knowledge, confidence and referral rat of neurological diseases / problems that primary care physicians encounter with statistical relation between means of each of these four items.

The factors suggested to improve neurology training of primary care physicians

The mean scores, median, mode, and skewness of methods which may be useful for improving neurology training were presented in Table 4. Most of the participants considered peer education, bedside tutorials and neurology rotation as the most important methods of improving neurology education. Cronbach’s alpha value for these items was 0.82 (Item-total correlation was between 0.279-0.609). Of the participants, 112 (26.3%) filled the free text section of the questionnaire. Implementation of teaching days during scientific organizations (n=61) live and free neurological consultation lines, or websites (n=42) were the most common themes in these open text suggestions.

| Methods | Mean* | Skewness | 95% Confidence Internal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Online resources | 3.13 ± 01 | -0.462 | 2.862 | 3.357 |

| Textbooks | 3.48 ± 1.2 | -0.388 | 3.311 | 3.785 |

| TASK† | 3.77 ± 1.1 | -0.886 | 3.459 | 3.966 |

| Problem Based Learning | 3.83 ± 0.07 | -0.316 | 3.604 | 3.930 |

| Lectures | 3.93 ± 0.08 | -0.201 | 3.667 | 4.022 |

| Clinical skills training | 4.12 ± 1.0 | -1.371 | 3.951 | 4.377 |

| Rotation | 4.19 ± 0.8 | -0.499 | 3.994 | 4.362 |

| Bedside tutorials | 4.32 ± 0.8 | -0.938 | 4.163 | 4.522 |

| Peers (Neurologist supervisors) | 4.45 ± 0.08 | -1.295 | 4.304 | 4.649 |

†Special undergraduate neurology module

Table 4: The mean, median, mode and skewness of methods which may be useful for neurology training and their estimated marginal means results in repeated measures test.

Discussion

After the introduction of the term ‘neurophobia,' several studies from distinct parts of the world have investigated this phenomenon [12-16]. Participants of these studies were selected mostly among the medical students and the residents of family physician programs [6,7,9-11,13-16]. To our best knowledge, however, we conducted the first study that investigates neurophobia in clinically experienced primary care physicians. Our results revealed that neurophobia is an unpleasant fact for primary care physicians. The primary care physicians who had participated in our study stated that they had less knowledge, interest and professional confidence in neurology compared to other specialties. They also perceived neurology harder than other specialties. Although there are several studies which confirm our results [6,7,10,13,14], Flanagan et al. [9] find out that primary care physicians rank their neurology knowledge at the third lowest level after geriatrics, rheumatology, and nephrology. We also add oncology and hematology to the list of other specialties that were compared with neurology. So far these two specialties are neglected in former studies on the same topic. Interestingly our results revealed that when compared with neurology not only primary care physicians got similar scores in hematology; they got less knowledge, interest, professional confidence and higher perceived hardness for oncology. This finding is interesting, and we need more data to offer an explanation.

The primary care physicians are expected to accomplish different clinical roles (prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, etc.) for a broad range of neurological diseases/ problems. Therefore, it is essential for them to be comfortable with dealing with the diseases of the neurological system. To reveal family physicians attitudes towards several clinical neurological problems/diseases, we asked the frequency, professional confidence, knowledge and referral rates related to each neurological disorder. Then, we analyze the relationship between these four items in each disease/problem. In agreement with the data of WHO [18], the most frequent three neurological problems encountered by primary care physicians were headache, epilepsy, and dizziness respectively. Our results showed that the frequency, knowledge, professional confidence and referral rates of each of the diseases might be different from each other. For instance, there was a difference between the referral rates and frequency and between the referral rate and knowledge for headache; this difference was statistically significant. This result can be interpreted as increasing knowledge levels resulted in a lower referral in headache patients. Additionally, there was a significant difference (negative correlation) between the referral rate and knowledge and between the referral rate and confidence in epilepsy and cerebrovascular diseases. This result can be partly explained with the condition that as most of the time primary care physicians learn after a patient had a cerebrovascular event. However, the role of primary care physicians in preventing a relapse of a cerebrovascular event can be best achieved in primary care by regulating risk factors (blood pressure, diabetes, etc.) [19]. The results related to epilepsy are also disappointing since most of the convulsive conditions, except certain conditions like status epilepticus, can be diagnosed and treated in primary care [20]. There was a statistically significant difference (negative correlation) between the referral rate and frequency in neuropathies, vertebral disorders, neurological infections, Alzheimer’s disease, vertigo and sleep disorders. These results couldn't be just explained by the limited clinical role of primary care physician in several diseases (Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, etc) but they are alarming as they could be interpreted as primary care physicians tend to refer most of these patients. For example, the primary care physician's role in early diagnosis, screening, and assessment of daily functions, behavioral symptoms, and caregiver status is vital in dementia [21,22].

The second aim of this study was to determine possible reasons for neurophobia in primary care physicians. The several factors for neurophobia which are discussed in the previous studies can be divided into three main groups (undergraduate and postgraduate neurological training and others) with regards to primary care [6-11,13-15]. Among these factors, one of the most important factors for neurophobia is the perception of neurology depending on a stereotypical point of view to neurology specialists, and neurological sciences of primary care physicians and patients were claimed [17]. However, our results showed that many of our participants (36%) don't believe neurology's reputation as a tough subject is an important factor for neurophobia. The other factor that is discussed previously is the highly specialized and specific content of neurology [13,14]. For instance, to diagnose, treat and follow-up headache a 30-step algorithm is needed [23]. Most of our participants believe that neurological diseases are progressive with no special treatment. It is not easy for a primary care physician to understand and to explain several neurological diseases and problems such as multiple sclerosis and motor neuron diseases to the patients [11].

Neurophobia often starts during undergraduate medical education. Most of our participants (>50%) stated that undergraduate neurology training is far from satisfactory and it focuses on rare diseases. Also, they stated that they had limited time and clinical experience. Many of them believe that neurologic physical examination is too complex. One of the main concerns about the factors causing neurophobia in undergraduate education is that neurological training mostly focuses on detailed, comprehensive and complex neuroanatomical and neurophysiology for basic physical examination and diagnosis, which is also confirmed by our participants [14]. Parallel to our results, participants in several studies demand improvements and simplification in neuroanatomy and physiology education [9]. The other common concern of the participants in our study was the ineffective bedside tutorials. In several studies, limited bedside tutorials and patient exposure were also brought to attention [14,15,23]. Warlow et al. [23] pointed out that small group of students instead of larger ones is the critical factor for the efficacy of bedside tutorials. In addition, to increase the efficiency of bedside tutorials, experimental learning circle models are defined [24]. In this model, four components (active experimentation, concrete experience, relative observation and abstract conceptualization) are linked with each other.

Furthermore, there is substantial evidence that primary care physicians can't benefit enough from their postgraduate neurological training [6,25,26]. Residents mostly have to depend on their fundamental undergraduate neurological training for their clinical workload. Our results confirm this situation as most of our participants believe that their postgraduate neurology training and their clinical experience with neurologic patients are limited. To increase the affectivity of neurology training in residency programs, our participants underlined once again the importance of bedside tutorials with neurologist supervisors, similar to undergraduate education. Most of the participants in our study stated that a neurology rotation, neurological clinical skills training, and lectures would be very useful. It is not surprising that problem-based learning is not so much popular although it was recommended in several relevant studies [27,28]. Problem-based learning is a new concept in Turkey, and only a handful of primary care physicians had the opportunity to experience this learning so far. The web-based learning was not popular in our study compared with other methods although several researchers underlined the possible benefits of using virtual patient cases with e-learning [27,29,30]. To set minimum standards, several family physician organizations recommend curriculum guidelines for neurology. However, each residency program is mostly responsible for its curriculum [31]. Some researchers stated that this training must include simple, integrated and cooperative content but most importantly it must concentrate on the clinical experience of the primary care physicians [32]. To identify the needs of primary care physicians, the residency curriculum designers must have accurate and detailed data on the neurology workload in a primary care setting.

Must-know guidelines are also developed to help first-line primary care physicians in several crucial topics. Our study also revealed that primary care physicians demand high cooperation with neurologists (consultation lines etc.) with specialized training.

However, our study has some limitations. First of all, the participants in our study have graduated from different medical universities, and it is possible if any of these universities have favourable conditions for neurology training for primary care. Our results based on subjective variables highly depending on participants. Although the participants in this study were selected from primary care physicians who were working in different cities of Turkey, these results can't be generalized.

In conclusion, our results indicated that "neurophobia" is present in the primary care physicians. The primary care physicians demand a better neurology education at both undergraduate and post-graduate levels, besides, liveconsultation capability with neurologists in special occasions. Similar studies are needed to confirm our results in primary care. The next step must be interventional studies with high reliability and validity to reduce neurophobia among primary care physicians [16,26].

References

- Popp AJ, Deshaies EM. A guide to the primary care of neurological disorders (2ndedn) In Maugans Todd. Primary care and its relationship to the clinical neurosciences. New York. Thieme Medical Publishers 2007; 3-18.

- Joynt RJ. Neurogenetics and primary care. Neurology 1997; 48: 2-3.

- Hopkins A. Lessons for neurologists from the United Kingdom third national morbidity survey. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1989; 52: 430-433.

- Papapetropoulos T, Tsibre E, Pelekoudas V. The neurological content of general practice. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1989; 52: 434-435.

- Murray TJ. What should a family physician know about neurology? Can Fam Physician 1990; 36: 297-299.

- McCarron MO, Stevenson M, Loftus A.M, McKeown P. Neurophobia among general practice trainees: The evidence, perceived causes and solutions. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2014; 122: 124-128.

- Murray TJ. Concepts in undergraduate neurological teaching. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1977; 79: 273-284.

- Jozefowicz RF. Neurophobia: the fear of neurology among medical students. Arch Neurol 1994; 51: 328-329.

- Flanagan E, Walsh C, Tubridy N. 'Neurophobia'--attitudes of medical students and doctors in Ireland to neurological teaching. Eur J Neurol 2007; 14: 1109-1112.

- Nham B. Graded exposure to neurophobia: Stopping it affect another generation of students. Aus Med Stud J 2012; 3: 76-78.

- Ridsdale L, Massey R, Clark L. Preventing neurophobia in medical students, and so future doctors. Pract Neurol 2007; 7: 116-123.

- Kern DE, Thomas PA, Howard DM, Bass EB. Curriculum development for medical education: a six step approach. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1998; 4-7.

- Handel AE, Ramagopalan SV. Has neurology been demystified? Lancet 2009; 373: 1763-1764.

- Youssef FF. Neurophobia and its implications: evidence from a Caribbean medical school. BMC Med Educ 2009; 9: 39.

- Zinchuk A, Flanaganz E, Tubridy N, Miller W, McCullough L. Attudes of US medical trainees towards neurology educaton: “Neurophobia” - a global issue. BMC Med Educ. 2010; 10: 49.

- McGee J, Maghzi AH, Minegar A. Neurophobia: A global and under-recognized phenomenon. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2014; 122: 3-4.

- Schon F, Hart P, Fernandez C. Is clinical neurology really so difficult? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72: 557-559.

- WHO. Neurology atlas 2004.

- Mackay-Lyons M, Thornton M, Ruggles T, Che M. Non-pharmacological interventions for preventing secondary vascular events after stroke or transient ischemic attack. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 28: CD008656.

- Elliott J, Shnekar B. Patient, care giver, and health care practioner knowledge of beliefs about, and attitudes towards epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2008; 12: 547-556.

- Galvin JE, Sadowsky CH; NINCDS-ADRDA. Practical guidelines for the recognition and diagnosis of dementia. J Am Board Fam Med 2012; 25: 367-382.

- Beithon J, Gallenberg M, Johnson K, Kildahl P, Krenik J, Liebow M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Headache. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement.

- Warlow C. Teaching medical students’ clinical neurology, an old codger’s view. Clin Teach 2005; 2: 111-114.

- Emsley H. Improving undergraduate clinical neurology bedside teaching: opening the magic circle. Clin Teach 2009; 6: 172-176.

- Matthias AT, Nagasingha P, Ranasinghe P, Gunatilake SB. Neurophobia among medical students and non-specialist doctors in Sri Lanka. BMC Med Educ 2013; 13: 164.

- McColgan P, McKeown PP, Selai C, Doherty-Allan R, McCarron MO. Educational interventions in neurology: a comprehensive systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2013; 20: 1006-1016.

- Hudson JN. Linking neuroscience theory to practice to help overcome student fear of neurology. Med Teach 2006; 28: 651-653.

- Heckmann JG, Dütsch M, Rauch C, Lang C, Weih M.. Effects of peer-assisted training during the neurology clerkship: a randomized controlled study. Eur J Neurol 2008; 15: 1365-1370.

- Lim EC, Ong BK, Seet RC. Using videotaped vignettes to teach medical students to perform the neurologic examination. J Gen Intern MED 2006; 21: 101.

- Levinson AJ, Weaver B, Garside S, McGinn H, Norman GR. Virtual reality and brain anatomy: a randomised trial of e-learning instructional designs. Med Educ 2007; 41: 495-501.

- Bauer D, Moquist DC. Family Practice Curriculum in Neurology.American Academy of Neurology (2ndedn) American Academy of Family Physicians. Conditions of Nervous System: Recommended Curriculum Guidelines for Family Medicine Residents.

- Ford H. Teaching medical students clinical neurology: a ‘young thing’s’ view. Clin Teach 2005; 2: 115-117.