Research Article - Journal of Clinical Dentistry and Oral Health (2022) Volume 6, Issue 1

Matrix band used for restoration of class II amalgam cavities in university set up

Babu V and Deepak S*

Department of Conservative Dentistry And Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, India

- Corresponding Author:

- Deepak S

Department of Conservative and Endodontics

Saveetha Dental College

Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences

Saveetha University, Chennai, India

E-mail: deepaks.sdc@saveetha.com

Received: 01-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. AACDOH-22-52400; Editor assigned: 04-Jan-2022, PreQC No. 04-Jan-2022 AACDOH-22-52400 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Jan-2022, QC No. AACDOH-22-52400; Revised: 21-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. AACDOH-22-52400 (R); Published: 28-Jan-2022, DOI: 10.35841/aacdoh-6.1.105

Citation:Babu V, Deepak S. Matrix band used for restoration of class II amalgam cavities in university set up. J Clin Dentistry Oral Health. 2022; 6(1):16-22.

Abstract

Aim and Background Dental students commonly face the problem of overhanging proximal margins and unsatisfactory proximal contact points while restoring Class II cavities in posterior teeth. Various matrix band systems are used in dental clinics to avoid such problems and ease of the dentist. The aim of the study was to evaluate the prevalence of use of various types of matrix band in Class II Amalgam restoration in a university setup. Methodology A cross sectional retrospective study of, with a study population of 1567 patients visiting Saveetha Dental College and Hospital who had been treated with Class II Amalgam, the use of different types of matrix bands were noted. The data was tabulated and analysed. SPSS by IBM was used for data analysis The Statistical test used was the Chi Square test. Results The gender prevalence of patients included in the study, which shows that 807 of them were male (51.5%) and 760 of them were female (48.5%). The most common age group was 31 to 40 years of age were 515 patients in the age group of (32.9%). The disto occlusal Class II caries was found to be 801 of the total tooth (51.1%) which is most common of all. 467 of the affected tooth was maxillary premolar (29.8%) which is found to be common tooth for class II caries. 1055 of them used tofflemire for retainer (67.3%) which is the most common retainer and matrix band used. Conclusion From the conducted study we see that males were most commonly affected by class II caries. We also saw that the most common age group was 31 to 40 years of age. Maxillary premolar are the most common tooth to be affected by class II caries. Disto Occlusal caries are common of class II caries. Tofflemire retainer is the standard of matrix band used in the university setup. There is a need to increase the knowledge and uses of ivory retainer as it is easy to use and has a tight contact.

Keywords

Matrix Band, Class II Cavities, Contacts and Contours

Introduction

The direct restoration of a Class II preparation to re-establish form and function requires the use of a matrix system. Two potential problems associated with this procedure include firstly, the ability to restore a contact point with the adjacent tooth surface(s), which is essential to prevent food packing, and secondly, the capability to prevent extrusion of excess restorative material at the gingival margin of the preparation. Such excess may cause periodontal problems including significant loss of alveolar bone [1].

Improper matrix band placement could result in poor contours or contacts, overhangs as well as weakness resulting from poorly condensed restorative material. A variety of wedges are available to aid contouring the matrix to the cavity with the aim of reducing the extrusion of excess dental material and production of an overhang [2]. The primary function of the matrix is to restore anatomic proximal contours and contact areas. A properly placed matrix should be rigid against the existing tooth structure. It should help in establishing a proper anatomic contour. It has to restore the correct proximal contact relation. Prevent gingival overhang has to be established by the matrix band. It should be able to be easily removed by the dentist.

Creation of anatomically optimum contact points with direct restorations still remains difficult [3,4]. Posterior restorations can frequently exhibit various problems, for example, improper contact points, proximal overhangs, etc [5]. Improper condensation of the restorative material and polymerization shrinkage of restorative material may be responsible for these problems [6,7]. A contact which is not adequate usually results in food impaction, periodontal disease, and movement of tooth [8,9].

Matrix band system is used to restore cavities with missing proximal walls [4]. Circumferential matrix band system has been conventionally used to restore the Class II cavities [10]. Sectional matrix band system is relatively new and has shown to produce anatomically optimum contact points [11,12].

Sectional Matrix System is designed to create tight, anatomical contacts on Class II restorations. The system is made up of three components: bands, rings and wedges. Ivory matrix band retainer holds the matrix band that encircles the tooth to provide missing walls on both proximal sides. The matrix band is made up of a thin sheet of metal so that it can pass through the contact area of the unprepared proximal side of the tooth. The circumference of the band can be adjusted using the screw present in the matrix band retainer. The Universal (Tofflemire) matrix system is used in Class II restorations. The parts are 1. Head – U-shaped has three guides, or slots, for the position of the band 2. Locking vise - sliding body that holds the band 3. Long knob – changes the diameter of the loop 4. Short knob – locks the band in place within the sliding body.

Our team has extensive knowledge and research experience that has translate into high quality publications [13-32].

Objective

The objective of the study was to evaluate the prevalence of use of various types of matrix band in Class II Amalgam restoration in a university setup.

Materials and Method

Study design

A prevalence study.

Study setting

OPD Department in a private dental institution in Chennai.

Study size

1567 outpatients attending the OPD department.

Sampling and scheduling

Owing to the nature of the study design and setting, a convenience sampling method was used, and the data was collected.

Survey instrument

An online platform called DIAS was used to collect the data and the data of patients undergoing trans alveolar extraction was tabulated and analysed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All those who underwent Class II Amalgam restoration in Saveetha Dental College and Hospital were included in the study. Patients who restores with indirect Class II restoration were not included in the study.

Ethical clearance

Prior to the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the institution ethical committee of Saveetha University.

Statistical analysis

The collected data was tabulated in excel and were then imported to SPSS by IBM software, (version 25). Descriptive statistics were done using frequency and percentage. Inferential statistics were done using the Chi-square test. Interpretation was based on a p value less than 0.05, which was considered statistically significant. Comparisons were done between independent variables like age, gender, occupation and knowledge, attitude, practice responses by the participants.

Result and Discussion

From the study of 1567 class II amalgam restored teeth with the help of matrix band we see that out of all the participants 807 of them were male (51.5%) and 760 of them were female (48.5%). In a study conducted by Monica Antony showed Male study population was 50.71% and the female population was 49.29%, this correlates to the current study that males are prone to caries. In another study conducted by John R Lukacs shoed among the Guanches, corrected tooth-count caries rates for females (8.8%, 158/1,790) are approximately twice the frequency of caries among males (4.5%, 68/1,498) this does not correlate with the study [33].

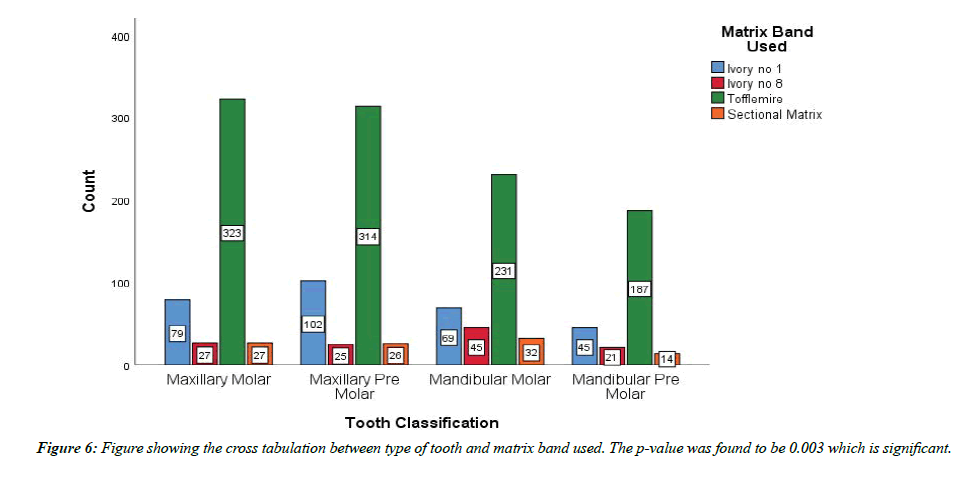

In the study the age distribution was identified, which shows that 27 of them were below 20 years of age (1.7%), 444 of tem were between the age group of 20 to 30 years of age (28.3%), there were 515 patients in the age group of 31 to 40 years of age (32.9%). 365 of them were in the age group of 41 to 50 years of age (23.3%) and 216 of them were above the age of 50 years (13.8%). In a study conducted by Blerim Kamberi showed that the prevalence of caries for the whole study was 72.80%, and it decreased with age: 18–34 years (88.80%), 34–44 years (77.90%), 45–64 years (65.50%), 65–74 years (42.40%), and 75+ years (20.90%) [34]. In the study we saw that Class II mesio occlusal caries was 746 of the total carious tooth (47.6%), the disto occlusal Class II caries was found to be 801 of the total tooth (51.1%) and only 20 of the tooth were affected with both mesial and disto occlusal caries (1.3%). The Tabulation of carious tooth showed that 456 of the affected tooth was maxillary molars (18.8%), 467 of the affected tooth was maxillary premolar (29.8%), 377 of the affected tooth was mandibular molar (24.1%) and 267 of the tooth was mandibular premolar (17.0%). According to a study conducted by Mustafa Demirci, Regarding the distribution of caries within individual teeth, the first and second maxillary molars were most susceptible to caries at 11.5%, while the mandibular central incisors were least susceptible, at 1.7%. Caries distribution was higher in the maxillary jaw (62.4%) than in the mandibular jaw (37.6%) (Figures 1 to Figure 7).

Figure 2:Figure showing age distribution of the individuals of the study, in which we see that 27 of them were below 20 years of age (1.7%), 444 of tem were between the age group of 20 to 30 years of age (28.3%), there were 515 patients in the age group of 31 to 40 years of age (32.9%). 365 of them were in the age group of 41 to 50 years of age (23.3%) and 216 of them were above the age of 50 years (13.8%).

Figure 3:Figure shows prevalence of type of caries which shows that Class II mesio occlusal caries was 746 of the total carious tooth (47.6%), the disto occlusal Class II caries was found to be 801 of the total tooth (51.1%) and only 20 of the tooth were affected with both mesial and disto occlusal caries (1.3%).

Figure 4:Figure showing the prevalence of maxillary molars versus mandibular molars and we saw that456 of the affected tooth was maxillary molars (18.8%), 467 of the affected tooth was maxillary premolar (29.8%), 377 of the affected tooth was mandibular molar (24.1%) and 267 of the tooth was mandibular premolar (17.0%).

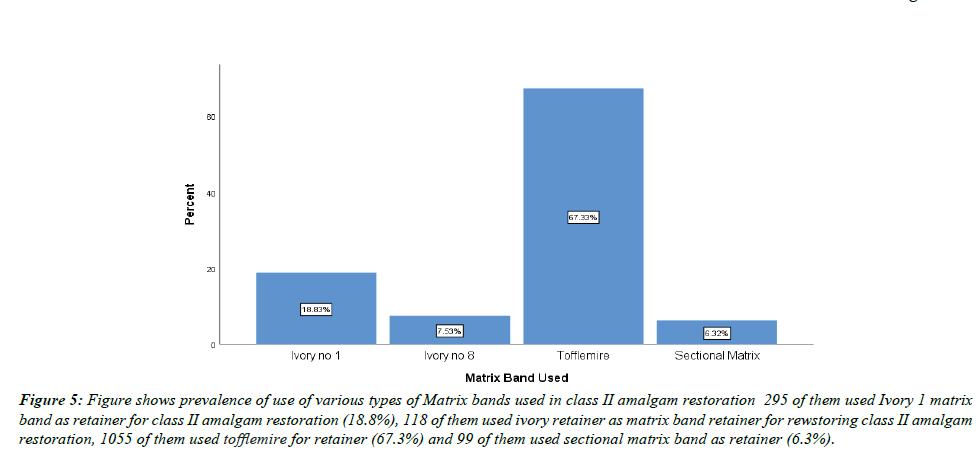

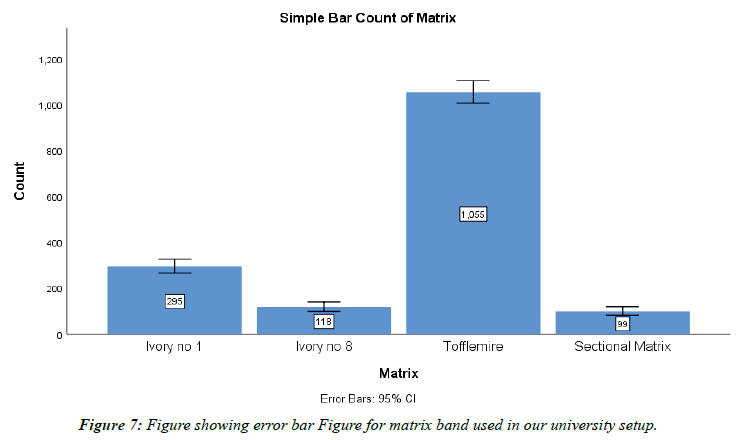

Figure 5:Figure shows prevalence of use of various types of Matrix bands used in class II amalgam restoration 295 of them used Ivory 1 matrix band as retainer for class II amalgam restoration (18.8%), 118 of them used ivory retainer as matrix band retainer for rewstoring class II amalgam restoration, 1055 of them used tofflemire for retainer (67.3%) and 99 of them used sectional matrix band as retainer (6.3%).

Among the various types of retainer used in the university 295 of them used Ivory 1 matrix band as retainer for class II amalgam restoration (18.8%), 118 of them used ivory retainer as matrix band retainer for rewstoring class II amalgam restoration, 1055 of them used tofflemire for retainer (67.3%) and 99 of them used sectional matrix band as retainer (6.3%). There are a number of studies that showed that a sectional matrix band with separation ring is the most reliable device for restoring contact points in posterior teeth. A study conducted by Loomans et al. in 2005 compared circumferential band and sectional band found that the sectional matrix band with separation ring helps establish greater strength of the contact points [35]. A strong association between restoration overhang and different matrix band systems also has been found, and no restoration overhang was found in cavities restored with sectional band systems. An optimum proximal contour can also be achieved with a sectional matrix band with separation ring [35]. A cross tabulation between type of tooth and matrix band used was done. The p-value was found to be 0.003 which is significant.

Conclusion

From the conducted study we see that males were most commonly affected by class II caries. We also saw that the most common age group was 31 to 40 years of age. Maxillary premolar are the most common tooth to be affected by class II caries. Disto Occlusal caries are common of class II caries. Tofflemire retainer is the standard of matrix band used in the university setup. There is a need to increase the knowledge and uses of sectional matrix band as it is easy to use and has a tight contact.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Saveetha Dental college for all the help and support.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Source of Funding

The present project is supported by

Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Science, Saveetha University, India.

Geetha Foundations and Flat Promoters.

References

- Parsell DE, Streckfus CF, Stewart BM, et al. The effect of amalgam overhangs on alveolar bone height as a function of patient age and overhang width. Oper Dent. 1998;23:94-9.

- Qualtrough AJ, Wilson NH. The history, development and use of interproximal wedges in clinical practice. Dent Update. 1991;18(2):66-70.

- Santos MJ. A restorative approach for class ii resin composite restorations: a two-year follow-up. Oper Dent. 2015;40(1):19-24.

- Wirsching E, Loomans BA, Klaiber B, et al. Influence of matrix systems on proximal contact tightness of 2-and 3-surface posterior composite restorations in vivo. J Dent. 2011;39(5):386-90.

- Quadir F, Ali Abidi SY, Ahmed S. Overhanging amalgam restorations by undergraduate students. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2014;24(7):485-8.

- Burke FJ, Shortall AC. Successful restoration of load-bearing cavities in posterior teeth with direct-replacement resin-based composite. Dent Update. 2001;28(8):388-98.

- Dörfer CE, Schriever A, Heidemann D, et al. Influence of rubber-dam on the reconstruction of proximal contacts with adhesive tooth-colored restorations. J Adh Dent. 2001;3(2):169-75.

- Abrams H, Kopczyk RA. Gingival sequela from a retained piece of dental floss. J Am Dent Assoc.1983;106(1):57-8.

- Kamel JH.Retention of Posterior Composite Resin Restorations(Doctoral dissertation, University of Dundee).

- Van der Vyver PJ. Posterior composite resin restorations. Part 3. Matrix systems. SADJ. 2002;57(6):221-6.

- Loomans BA, Opdam NJ, Roeters FJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial on proximal contacts of posterior composites. J Dent. 2006;34(4):292-7.

- Kim HS, Na HJ, Kim HJ, et al. Evaluation of proximal contact strength by postural changes. J Adv Prosthodont. 2009;1(3):118-23.

- Muthukrishnan L. Imminent antimicrobial bioink deploying cellulose, alginate, EPS and synthetic polymers for 3D bioprinting of tissue constructs. Carbo Poly. 2021;260:117774.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Nivedhitha MS, et al. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures by cone-beam computed tomography in root-filled teeth with confirmation by direct visualization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endo. 2021;47(8):1198-214.

- Chakraborty T, Jamal RF, Battineni G, et al. A review of prolonged post-COVID-19 symptoms and their implications on dental management. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5131.

- Muthukrishnan L. Nanotechnology for cleaner leather production: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19(3):2527-49.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Is a filled lateral canal–A sign of superiority?. J Dent Sci. 2020;15(4):562.

- Narendran K, MS N, Sarvanan A. Synthesis, Characterization, Free Radical Scavenging and Cytotoxic Activities of Phenylvilangin, a Substituted Dimer of Embelin. Ind J Pharmac Sci. 2020;82(5):909-12.

- Reddy P, Krithikadatta J, Srinivasan V, et al. Dental caries profile and associated risk factors among adolescent school children in an urban South-Indian city. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2020;18(1):379-86.

- Sawant K, Pawar AM, Banga KS, et al. Dentinal Microcracks after Root Canal Instrumentation Using Instruments Manufactured with Different NiTi Alloys and the SAF System: A Systematic Review. App Sci. 2021;11(11):4984.

- Bhavikatti SK, Karobari MI, Zainuddin SL, et al. Investigating the Antioxidant and Cytocompatibility of Mimusops elengi Linn Extract over Human Gingival Fibroblast Cells. Int J Enviro Res Public Hea. 2021;18(13):7162.

- Karobari MI, Basheer SN, Sayed FR, et al. An In Vitro Stereomicroscopic Evaluation of Bioactivity between Neo MTA Plus, Pro Root MTA, BIODENTINE & Glass Ionomer Cement Using Dye Penetration Method. Mat. 2021;14(12):3159.

- Rohit Singh T, Ezhilarasan D. Ethanolic extract of Lagerstroemia Speciosa (L.) Pers., induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in HepG2 cells. Nutr Cancer. 2020;72(1):146-56.

- Ezhilarasan D. MicroRNA interplay between hepatic stellate cell quiescence and activation. Euro J Pharmacol. 2020;885:173507.

- Romera A, Peredpaya S, Shparyk Y, et al. Bevacizumab biosimilar BEVZ92 versus reference bevacizumab in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(12):845-55.

- Raj R K. β?Sitosterol?assisted silver nanoparticles activates Nrf2 and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis via oxidative stress in human hepatocellular cancer cell line. J Biomed Mat Res Part A. 2020;108(9):1899-908.

- Vijayashree Priyadharsini J. In silico validation of the non?antibiotic drugs acetaminophen and ibuprofen as antibacterial agents against red complex pathogens. J Periodontol. 2019;90(12):1441-8.

- Priyadharsini JV, Girija AS, Paramasivam A. In silico analysis of virulence genes in an emerging dental pathogen A. baumannii and related species. Archiv Oral Biol. 2018;94:93-8.

- Uma Maheswari TN, Nivedhitha MS, Ramani P. Expression profile of salivary micro RNA-21 and 31 in oral potentially malignant disorders. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34.

- Gudipaneni RK, Alam MK, Patil SR, et al. Measurement of the maximum occlusal bite force and its relation to the caries spectrum of first permanent molars in early permanent dentition. J Clini Pediatr Dent. 2020;44(6):423-8.

- Chaturvedula BB, Muthukrishnan A, Bhuvaraghan A, et al. Dens invaginatus: a review and orthodontic implications. Br Dent J. 2021;230(6):345-50.

- Kanniah P, Radhamani J, Chelliah P, et al. Green synthesis of multifaceted silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Aerva lanata and evaluation of its biological and environmental applications. Chem Select. 2020;5(7):2322-31.

- Lukacs JR, Largaespada LL. Explaining sex differences in dental caries prevalence: Saliva, hormones, and “life?history” etiologies. Am J Hum Biol. 2006;18(4):540-55.

- Kamberi B, Koçani F, Begzati A, et al. Prevalence of dental caries in Kosovar adult population. Int J Dent. 2016;2016.

- Loomans BA, Opdam NJ, Roeters FJ, et al. Comparison of proximal contacts of Class II resin composite restorations in vitro. Oper Dent. 2006;31(6):688-93.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Google Scholar Cross Ref Indexing

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref