Research Article - Asian Journal of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences (2019) Volume 9, Issue 67

Kinetic properties of Rhodanese from African locust bean seeds (Parkia biglobosa)

Adeola Folashade Ehigie, Mohammed Adewumi Abdulrasak, Fiyinfoluwa D Ojeniyi and Ona Leonard Ehigie*

Department of Biochemistry, College of Health Sciences, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso, Nigeria

- Corresponding Author:

- Ona Leonard Ehigie

Department of Biochemistry Ladoke

Akintola University of Technology Ogbomoso, Nigeria

E-mail: Lehigie@lautech.edu.ng

Accepted date: June 05, 2019

Citation: Adeola Folashade Ehigie et.al. Kinetic properties of Rhodanese from African locust bean seeds (Parkia biglobosa). Asian J Biomed Pharmaceut Sci. 2019;9(67):18-23.

DOI: 10.35841/2249-622X.67.19-215

Visit for more related articles at Asian Journal of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical SciencesAbstract

African locust bean (Parkia biglobosa) is a legume which can be processed into condiment. Rhodanese is a sulphurtransferase enzyme. It catalyses the degradation of cyanide to a less toxic metabolite, thiocyanate. Rhodanese purication and biochemical characterization were carried out in this study. The activity of this enzyme from Parkia biglobosa was evaluated and the kinetics of the rhodanese enzyme reaction, including pH and temperature profiles, substrate specificity and effects of metal ions were assessed. Studies on the rhodanese enzyme from other systems have been compared with the results of this study. Rhodanese was isolated from Parkia biglobosa and purified using ammonium sulphate precipitation, CM-Sephadex, and Reactive Blue 2-agarose column chromatography. The purified enzyme has a specific activity of 3.69 RU/mg with a percent yield of 0.20. Km and Vmax values of 7.61 mM and 0.65 RU/ml/min were obtained respectively when KCN was used as a substrate while values of 11.59 mM and 0.57 RU/ml/min was obtained with Na2S2O3. The enzyme showed preference for sodium thiosulphate (Na2S2O3) among different substrates tested namely Mercapto-ethanol (HOCH2CH2SH), Ammonium per sulphate (NH4)2S2O8), Ammonium sulphate (NH4)2SO4), Sodium sulphate (Na2SO4), Sodium metabisulphite (Na2SO5). Optimum temperature and pH of 50?C and 8 were obtained respectively. Chloride salts tested showed little or no inhibitory effect at 1 mM concentration with the exception of HgCl2 and MnCl2. However at 10 mM concentration, the divalent metals; MnCl2 HgCl2, CaCl2, BaCl2 inhibited the enzyme. The present study showed that locust bean seeds possess a cyanide detoxifying enzyme with suitable kinetic properties which renders it safe for consumption.

Keywords

Sulphurtransferase enzyme, Enzyme reaction, Ammonium sulphate precipitation, Diarrhoea.

Introduction

Rhodanese (thiosulphate: cyanide sulphur transferase (E.C. 2.8.1.1)) is a ubiquitous enzyme found in all living organism across all kingdoms. It generates thiocyanate from a sulphur donor and free cyanide. Rhodanese also transfers sulphane sulphur from glutathione persulfide (GSSH) to sulphite producing thiosulphate and from thiosulphate to cyanide producing thiocyanate [1]. The enzyme has been documented to perform other physiological role in living organism other than cyanide detoxification which includes sulphur and selenium metabolism, synthesis or repair of iron-sulphur proteins [2], H2S detoxification [3], Neuromodulator [4].

African locust bean tree (Parkia biglobosa) is a perennial tree grown in Nigeria, especially in the North and South Western part of the country [5]. It is acclaimed for having nutritional, economic, industrial and medicinal importance [6]. The seed is processed by fermentation and used as condiment and helps to intensify meatiness in soups, sauces and other prepared dishes [7,8]. The condiment has different local names in Nigeria viz; Iru, dawadawa, ogiriigala etc.

Other than the nutritional benefits, the tree has several important uses namely; nitrogen fixation [9] enhances soil stability, nutrient cycling and provides shade [10]. The leaves, husks and pods can be processed into livestock feed [11,12]. The industrial uses include manufacture of soap, production of particle board [13].

Rosaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, or Gramineae family of plants is known to be cyanogenic [14]. Cyanide is an irreversible inhibitor of cytochrome c oxidase leading to inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation, reduction in ATP level, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and depolarization of mitochondria membrane leading to opening of permeability transition pore. Cyanide poisoning results in nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness, weakness, mental confusion, and convulsions followed by terminal coma and death [15]. Several factors contribute to cyan genesis including nature of soil, fertilizers application. There is gradual increase in HCN concentration as the plant ages [16].

This study was sought to investigate the presence of rhodanese enzyme in locust bean seeds by purifying and characterizing the protein from the locust bean seeds.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Biogel P-100 was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Benicia Ca., and USA. Other chemicals used were of analytical grade and were procured from reputed chemical firms. Glycerol, sodium acetate, sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), low molecular weight calibration kit for electrophoresis, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), Coomassie Brilliant- Blue, Blue Dextran, Reactive Blue-2 Agarose and Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company, St. Loius, Mo., USA. Potassium cyanide, nitric acid, sodium borate sodium citrate, formaldehyde, sodium thiosulphate, boric acid, ferric nitrite, citric acid, and ε-aminon- caproic acid were obtained from BDH Chemical Limited, Poole, England.

Plant material

Locust bean pods (Parkia biglobosa) were purchased from a local market in Ogbomoso, Nigeria. They were identified and authenticated at the Department of Biology, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso, Nigeria.

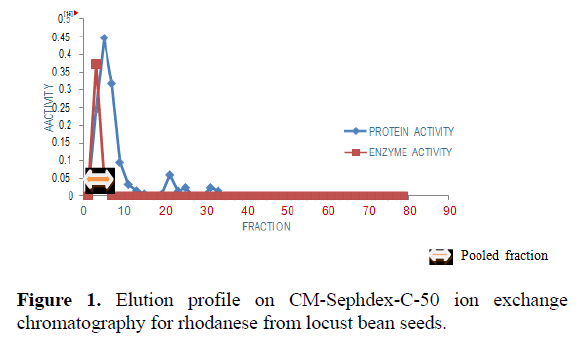

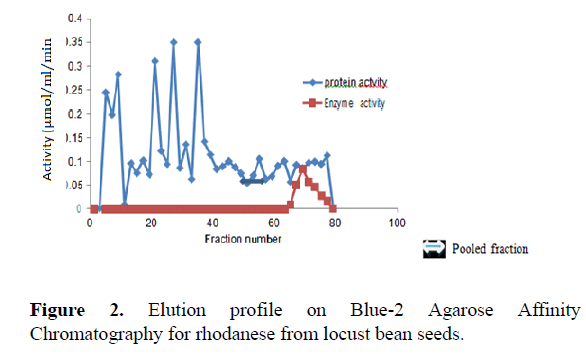

Enzyme extraction and isolation

The locust bean pods were washed and seeds were removed. The removed locust bean seeds were crushed with mortar and pestle. Hundred grams (100 g) of the crushed seeds were homogenized using a Warring blender in three volumes of homogenization mixture containing 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.5. After the removal of debris by centrifugation (4000 rpm at 10°C for 15 min) using Centurion cold centrifuge (R-1880), the supernatant fluid was filtered. Powdered ammonium sulphate was then added slowly to the supernatant fluid (100 ml) with occasional stirring for 1 h and left standing for 12 h at 4°C. After ammonium sulphate fractionation, the precipitated protein collected by centrifugation (4000 rpm for 30 min) was re suspended in 0.1 M Phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). The enzyme solution was concentrated by dialyzing against several changes of the Phosphate buffer and further centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was collected was assayed for enzyme activity and protein concentration was determined. Six milliliters (6 ml) of the concentrated enzyme solution was loaded onto a CM-Sephadex C-50 (25 × 40 mm, flow rate 48 ml per h) previously equilibrated with 0.1 M Phosphate buffer (pH 7.6). The enzyme was eluted with 0.5 m NaCl and 1.0 M NaCl in the same buffer and fractions (4 ml) were collected. The fractions that were enzymatically the most active were pooled and dialyzed against 50% glycerol in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.6). Three milliliters (3 ml) of the concentrated enzyme solution was loaded onto a Reactive Blue-2 Agarose resin (1.5 × 10 cm flow rate 12 ml per h) equilibrated with 0.05 M citrate buffer (pH 5.0). The enzyme was eluted with 1.0 M NaCl in the same buffer and fractions (2 ml) were collected. The fractions that were enzymatically the most active were pooled and dialyzed against 100 mL of 50% glycerol in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). The dialyzed fraction was assayed for enzyme activity and protein content.

Enzyme assay conditions

The assay for rhodanese was based on the methods of Sorbo and Aminlari et al. The reaction mixture contained 0.25 ml of 50 mM borate buffer (pH 9.4), 0.1 ml of 250 mM potassium cyanide, 0.1 ml of 250 mM sodium thiosulphate and 0.1 ml of the enzyme solution in a total volume of 0.55 ml. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 min, and the reaction was stopped with the addition of 0.25 mL of 15% formaldehyde. The production of thiocyanate was determined spectrophotometrically by the addition of 2.5 ml of 1% ferric nitrate (in 13% nitric acid) reagent and optical density reading was taken at 460 nm. One rhodanese unit was defined as that amount of enzyme which formed l mmol of thiocyanate during the 1 min incubation period. The reaction was linear with time during the 1 min incubation period.

Protein content determination

In this section, total protein was determined spectrophotometrically by Bradford reagent.

Analysis of kinetic data

The kinetic parameters of rhodanese enzyme were investigated by varying the concentration of sodium thiosulphate and potassium cyanide between 10 mM and 50mM at a fixed concentration of 25 mM potassium cyanide and sodium thiosulphate. The double reciprocal plot was applied to evaluate experimental data.

pH and temperature effects

Citrate buffer (0.1 M) (pH 3.0-6.0); Phosphate buffer (0.1 M) (pH 7.0-8.0) and Borate buffer (pH 9.0-10.0) were used to study the effect of pH changes. 0.25 mL of buffer was added to the reaction volume to make 1.0 ml. Temperature effects on enzyme activities were studied at different temperatures (30– 100°C) at pH 9.4.

Effectof salts on the catalysis

Chloride salts (monovalent and divalent) were tested to assess their relationship with enzyme activity. The salt solutions were buffered with 50 mM borate buffer (pH 9.4). The salts used include; NaCl, KCl, BaCl2, HgCl2 and MnCl2 at 0.001 mM, and 0.01 mM prepared from standard solutions of 0.1 mM.

Substrate specificity study

The specificity of the enzyme for different substrate was assessed using Mercapto-ethanol (HOCH2CH2SH), Ammonium per sulphate (NH4)2S2O2), Ammonium sulphate (NH4)2SO4), Sodium sulphite (Na2SO4), Sodium metabisulphate (Na2S2O5). The solutions of the compound (250 mM) were prepared in 50 mM borate buffer, pH 9.4 and assayed as described above.

Results

Purification

The result of the purification protocol for locust bean rhodanese showed a specific activity 5.09 RU/mg with yield of 0.06%. The purification procedure is summarized in Table 1. Figures 1 and 2 show elution profile on CM-Sephadex C-50 and Reactive Blue-2 Agarose respectively.

| Total Protein (mg) | Total Activity (U) | Specific Activity (u/mg) | Yield % |

Purification Fold | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Enzyme | 150.61 | 378.75 | 2.51 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 80% (NH4)2SO4 Precipitation | 33.7 | 105.77 | 3.14 | 0.28 | 1.25 |

| CM-Sephadex C-50 Ion Exchange Chromatography | 20.11 | 74.24 | 3.69 | 0.20 | 1.47 |

| Affinity 7.06 Chromatography |

7.06 | 36.79 | 5.21 | 0.10 | 2.07 |

Table 1. The purification profile of rhodanese from Locust bean seeds (Parkia biglobosa).

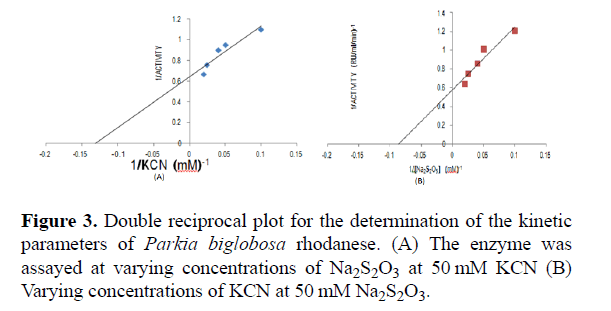

Kinetic parameters

Rhodanese followed Michaelis-Menten kinetics with a Km for sodium thiosulphate (Na2S2O3) of 13.95 mM with Vmax of 0.48 RU/ml/min estimated from a double reciprocal plot (Table 2 and Figure 3).

| Source | Specific Activity (RUmg1) | Purification Fold |

|---|---|---|

| Locust bean seed | 5.21 | 2.07 |

| Goat Liver | 1.55 | 1.88 |

| Cat fish rhodanese I | 73 | 49 |

| Cat fish rhodanese II | 72 | 48 |

| Topioca Leave | 5.74 | 7.8 |

| Zinginber officinale rhizome | 0.47 | 1.02 |

Table 2. Comparism of purification values of rhodenese from different sources.

The Km for potassium cyanide (KCN) of 11.14 mM with Vmax 0.46 RU/ml/min estimated from double reciprocal plot (Table 3 and Figure 3A).

| Substrate | Km | Vmax |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium cyanide | 7.61 | 0.65 |

| Sodium thiosulphate | 11.59 | 0.57 |

Table 3. Showing the Kinetic Values of the Potassium cyanide and Potassium cyanide substrates from Locust bean seeds rhodanese.

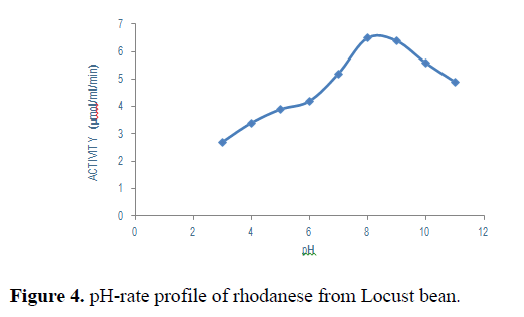

The effect of pH on the rate of rhodanese activity is shown in Figure 4. Rhodanese activity was found in pH ranging from 4 to 9. An optimum pH of 8 was obtained.

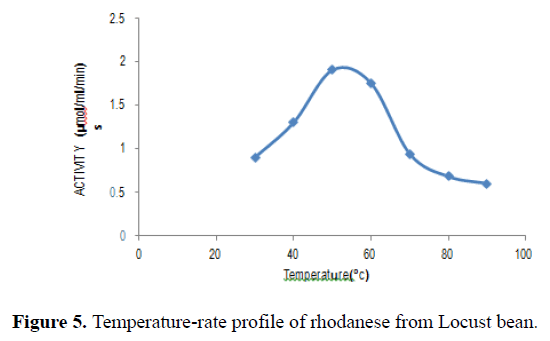

The effect of temperatures between 30°C to 100°C on the rhodanese activity showed that optimum temperature for the enzyme was 50°C (Figure 5).

The result of the effect of various sulphur compounds (inhibitors) on the activity of rhodanese is presented in Table 4. The activity is expressed relatively to the activity of the enzyme with sodium thiosulphate as the control. Percentage activity decreased in the order Na2S2O3>HOCH2CH2SH>(NH4)2S2O8>Na2S2O5. The effect of metal ions (NaCl, KCl, HgCl2, BaCl2, MnCl2) at concentrations of 1 mM and 10 mM was studied. The enzyme activity was inhibited by the divalent salts in the order HgCl2>MnCl2>BaCl2>CaCl2 in a concentration dependent manner while KCl, NaCl showed no inhibitory effect.

| Substrate | % Activity |

|---|---|

| Sodium Sulphate | 100 |

| Sodium Metabisulphite | 34.74 |

| Ammonium persulphate | 37.11 |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | 40.01 |

Table 4. Showing the Percentage Substrate Specificity of each Sulphur Compound from Locust bean seeds rhodanese.

Discussion

The presence of rhodanese activity has been studied in plants, such as on ginger, cabbage, and cassava [17-21]. The enzyme has been proposed to play a role in cyanide detoxification [20]. Hatzfeld and Saito (2000) were the first to isolate and characterize in plants two cDNAs encoding rhodanese isoforms in Arabidopsis thaliana, AtRDH1 and AtRDH2. In plants, a close relationship exists between cyanogenesis and rhodanese activity, which shows that the enzyme provides a mechanism for cyanide detoxification in cyanogenic plants [22,23].

Parkia biglobosa rhodanese was isolated and purified. The partially purified enzyme has a specific activity of 5.21 RU per mg of protein and 0.10% recovery (Table 1). Various purification values have been obtained for rhodanese from other sources as presented in Table 2.

Rhodanese catalysis is a non-sequential double displacement mechanism as was reported by Sorbo (1953) for bovine liver rhodanese. Either of the substrates may bind first to the rhodanese active site. Researchers on rhodanese have reported various affinities between the substrates. Locust bean seeds rhodanese had a higher affinity for potassium cyanide compared to sodium thiosulphate. This is similar to the affinitiy demonstrated by rhodanese from cytosol of fruit bat liver, hepatopancreas of Limicolaria flammea and guinea pig kidneys [24].

The apparent Km values of locust bean obtained from Lineweaver-Burk plots, for potassium cyanide and sodium thiosulphate were 7.61 and 11.59 mM, respectively (Tables 3-5). However, some other researchers reported a contrasting higher affinity for sodium thiosulphate compared to potassium cyanide. Such findings include that of rhodanese from Zinginber officinale rhizome, tapioca leaf, and goat liver [20,25,26].

| Chloride salts | % Residual Activity (1 mM) (µmole/ml/min) | % Residual Activity (10 mM) (µmole/ml/min) |

|---|---|---|

| HgCl2 | 70 | 68 |

| KCl | 95 | 94 |

| CaCl2 | 88 | 77 |

| NaCl | 98 | 95 |

| BaCl2 | 83 | 70 |

| MnCl2 | 75 | 63 |

Table 5. Effect of Metals on Rhodanese from Locust bean seeds.

pH-rate profiles reveals the role of acidic and basic functional groups in catalysis [27]. Figure 5 depicts the pH-rate profile for rhodanse extracted from Parkia biglobosa. With increase in pH level from 4 to 9, increase in activity was observed. The optimum activity was found to be at pH 8. Optima pH values of 7.0-11.0 have been reported. Akinsiku et al. [28,29] working on the African catfish liver obtained a pH value of 6.5. Ehigie et al. [20] reported for the ginger rhodanese an optimum pH of 9.0, Chew and Boey in 1972 worked on tapioca leaf and obtained a value of 10.2 to 11, Ebizimor reported for the sheep liver rhodanese of optimum pH of 8.5 and pH of 10.5 for the rainbow trout liver [30,31].

Activity of the enzyme was measured over the temperature range of 30°C to 100°C. The optimum temperature for Locust bean rhodanese was 50°C. This has been compared with that obtained from other sources (Table 6).

| Source | Optimum temperature | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Locust bean seed | 50°C | Present study |

| Bovine Liver | 50°C | Sorbo, 1953 |

| Mudskipper | 50°C | Okonji et al., |

| Trichoderma strains | 35-55°C | Ezzi et al., 2003 |

| Catfish | 40°C | Akinsiku et al., 2010 |

Table 6. Comparison of optimum temperature of rhodanese from different sources.

Sulphur compounds tested drastically reduced the activity of the enzyme which is a confirmation that the enzyme has preference for sodium thiosulphate as substrate compared to the others (Table 4). This is in agreement with the findings reported by Ehigie et al. and Okonji et al. Inbition studies provide a clue into the nature of the enzyme molecule and that of its active site. The inhibition my mercaptoethanol is evident of the presence of sulphur containing amino acids at the active site of the enzyme molecule. Mercaptoethanol disrupt protein structure by breaking disulphide bonds either intramolecular or intermolecular.

The influence of metal ions on the enzyme activity could be as a result of change in conformation of the enzyme molecule or change in the ionic interactions at the active site between the enzyme and the substrate. A number of metal ion binding residues in protein molecules have been identified e.g. cysteine, histidine, tyrosine, and asparagines [32-41]. The inhibition by metal ions (Table 5) used in this study may be due to local interactions with sulphurhydryl groups at the active center or change in the ionic nature of the whole molecule resulting into changes in the conformation of the enzyme. Further experimental procedures are required to fully elucidate the mechanism of inhibition.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study shows the presence of rhodanese in locust been seeds. The physicochemical characterization of the enzyme demonstrated similar characteristics with that from other sources. The plant benefit from the presence of rhodanese in cyanide detoxification and other notable functions of rhodanese.

References

- Adewumi BA. Developments in the technology of locust bean processing. J Tech Sci. 1997; 1: 9-14.

- Agboola FK, Okonji RE. Presence of Rhodanese in the cytosolic fraction of the fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) Liver. J Biochem Mol Bio 2004; 37: 275-281.

- Akande FB, Adejumo OA, Adamade CA, Bodunde J. Processing of locust bean fruits : Challenges and Prospects. African J Agricul Res 2010; 5: 2268-2271.

- Anosike EO, Ugochukwu EN. Characterization of Rhodanese from cassava leaves and tubers. J Experimet Botany 1981; 32: 1021-1027.

- Anosike EO, Jack AS. Kidney rhodanese from Guinea pig (Lepus caniculus) and Abino rat (Mus musculus). Enzyme 1982; 27: 33-39.

- Blain JC, Grisvard M. Plantes Veneneuses, la maison Rustique, Paris, France. Boey C, Yeoh H, Chew M. Purification of tapioca leaf rhodanese. Phytochemistry 1976; 15: 1343–1344

- Burns AE, Bradbury JH, Cavagnaro TR, Gleadow RM. Total cyanide content of cassava food products in Australia. J Food Compos Analysis 2012; 25: 79– 82.

- Campbell-Platt G. African locust bean (Parkia Species) and its West African fermented food product, Dawadawa. Ecol Food Nut 1980; 9: 123-132.

- Chew, M. Y. and Boey, C. G. Rhodanese of tapiocal leaf. Phytochemistry 1972; 11: 167-160.

- Chukwu O, Orhevba BA, Mahmood BI. Influence of hydrothermal treatments on proximate compositions of fermented locust bean (Dawadawa). J Food Tech 2010; 8: 99-101.

- Cipollone R, Ascenzi P, Visca P. Critical review: common themes and variations in the Rhodanese superfamily. IUBMB Life 2007; 59: 51–59.

- Cipollone R, Visca P. Is there evidence that cyanide can act as a neuromodulator? IUBMB Life, in press. 2007

- Cobley LS, Steele WM. An Introduction to the Botany of Tropical Crops. 2nd Ed. London. Longman. 1976.

- Douglas SJ. Tree Crops for Food Storage and Cash. Parts I and II. World Crops. 1972; 24: 15-19

- Drochioiu G, Arsene C, Murariu M, Oniscu C. Analysis of cyanogens with resorcinol and picrate. Food Chem Toxicol 2008; 46: 3540–3545.

- Ebizimor W. Effects of Temperature, pH and Some Monoatomic Sulphur Compounds on Rhodanese from Sheep Liver. J Nat Sci Res 2015; 5: 42-47.

- Ehigie OL, Okonji RE, Balogun RO, Bamitale KDS. Distribution of Enzymes (Rhodanese, 3-Mercaptopyruvate Sulphurtransferase, Arginase And Thiaminase) in Some Commonly Consumed Plant Tubers in Nigeria. 2nd International Conference on Engineering and Technology Research 2013; 4: 8-14.

- Elemo GN, Elemo BO, Oladunmoye OO, Erukainure OL. Comprehensive investigation into the nutritional composition of Dehulled and Defatted African Locust bean seed (Parkia biglobosa). African J Plant Sci 2011; 5: 291-295.

- Frehner M, Scalet M, Conn EE. Pattern of the cyanide potential in eveloping fruits: Implications for plants accumulating cyanogenic monoglucosides (Phaseolus lunatus) or cyanogenic diglucosides in their seeds (Linum usitatissimum, Prunus amygdalus). Plant Physiol 1990; 94: 28–34.

- Ehigie AF, Okonji RE, Abdulrasak MA, Ehigie LO. Partial Purification and Characterisation of Rhodanese from Zinginber officinale (Ginger). In: Olusola Ojurongbe (ed), Translating Research Findings into Policy in Developing Countries Contributions from Humboldt Kolleg Osogbo-2017; 88-100.

- Hamel J. A review of acute cyanide poisoning with a treatment update. Critical Care Nurse 2011; 31: 72–82.

- Hatzfeld Y, Saito K. Evidence for the existence of rhodanese (thiosulfate:cyanide sulfurtransferase) in plants: preliminary characterization of two rhodanese cDNAs from Arabidopsis thaliana. Federation of European Biochemical Societies (FEBS) Letters 2000; 470: 147-150.

- Hildebrandt TM, Grieshaber MK. Three enzymatic activities catalyze the oxidation of sulfide to thiosulfate in mammalian and invertebrate mitochondria. FEBSJ 2008; 275: 3352-3361.

- Lee CH, Hwang JH, Lee YS, Cho KS. Purification and characterization of mouse liver rhodanese. J Biochem Mol Biol 1995; 28: 170-176.

- Libiad M, Sriraman A, Banerjee R. Polymorphic Variants of Human Rhodanese Exhibit Differences In Thermal Stability And Sulfurtransfer Kinetics. Enzymology. J Biological Chem 2015; 1-23.

- Nagahara N, Ito T, Minam M. Mecaptopyruvate sulphurtransferase as a defence against cyanide toxications; Molecular properties and mode of detoxification. Histol Histopath 1999; 14: 1277-1286.

- Nagahara N, Nishino T. Role of Amino acid residues in the active site of rat liver mercapto pyruvate sulphur transferases. J Biol Chem 1996; 271: 27395-27401.

- Akinsiku OT, Agboola FK, Kuku A, Afolayan A. Physicochemical and kinetic characteristics of rhodanese from the liver of African catfish Clarias gariepinus Burchell in Asejire lake. Fish Physiol Biochem 2010; 36: 573–586.

- Obiazoba IC. Fermentation of African Locust Bean. Text on Nutrition Quality of Plant Fruits. Osagie, Eka (Ed). Post-Harvest Research Unit. Dept Biochem. UNIBEN. Nigeria. 2000; pp: 160-198.

- Odunfa SA. A Note of Microorganisms Associated with the Fermentation of African Locust Bean (Parkia species) during Iru Production. J Plant Foods 1981; 3: 245-250.

- Ogudugu BE, Ademakinwa NA, Ezinma EN, Agboola FK. Purification and Physicochemical Properties of Rhodanese from Liver of Goat, Capra Aegagrus Hircus. J Biochem Mol Biol Res 2015; 1: 105-111.

- Okonji RE, Adewole HA, Kuku A, Agboola FK. Physicochemical Properties of Mudskipper (Periophthalmus Barbarus Pallas) Liver Rhodanese. Australian J Basic Applied Sci 2011; 5: 507-514.

- Okonji RE, James IE, Madu JO, Fagbohunka BS, Agboola FK. Purification and Characterization of Rhodanese from the Hepatopancreas of Garden Snail, Limicolaria flammea. Ife J Sci 2015; 17: 289-303.

- Owolarafe OK, Adetan DA, Olatunde GA, Ajayi AO, Okoh IK. Development of a Locust Bean Processing Device. J Food Sci Tech 2011.

- Owoyale JA, Shok MA, Olagbemiro T. Some Chemical Constituents of the Fruits Parkia Clapppertoniare as Protein Industrial Raw Material. Paper Presented at the 2nd Annual Conference of Biotechnology Society of Nigeria. Unilorin, Ilorin. 1986.

- Smith J, Urbanska KM. Rhodanese Activity in Lotus corniculatus sensu-lato. J Nat Histol 1986; 20: 1467-1476.

- Sorbo BH, Crystalline R. Enzyme catalyzed reaction. Acta Chem Scand 1953; 7: 1137-1145.

- Tayefi-Nasrabadi H, Rahmani R. Partial purification and characterization of Rhodanese from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Liver. Sci World 2012: 1-5.

- Ulmer DD, Vallee BL. Role of metals in sulphurtransferase activity. Annual Rev Biochem. 1972; 32, 86-90.

- Westley J. Rhodanese and the sulphane pool, In: Enzymatic basis of detoxification. 1980; 245-259.

- Yudkin J. The pengrim encyclopaedia of nutrition. Richard Clay Ltd. Bungay; 1985; 222-230.