- Biomedical Research (2009) Volume 20, Issue 3

Interventional Role of Piperazine Citrate in Barium Chloride Induced Ventricular Arrhythmias in Anaesthetized Rats

Ghasi S*, Mbah AU, Nze PU1, Nwobodo E2, Ogbonna AO, Onuaguluchi G1Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 1Department of Anaesthesiology, University of Nigeria College of Medicine, Enugu, Nigeria,

2Department of Physiology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University College of Health Sciences, Nnewi, Nigeria

- *Corresponding Author:

- S. Ghasi

Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics

University of Nigeria College of Medicine

Enugu, Nigeria.

E-mail: samuelghasi@yahoo.com

Accepted date: April 25 2009

Abstract

Interventional potential of piperazine in Barium Chloride (BC) -induced ventricular arrhythmias was investigated in the rats. Various forms of arrhythmias were induced in 10 rats and piperazine (30mg/kg) was given in each case to reverse arrhythmia to sinus rhythm. Five out of six cases of induced ventricular tachycardia (83.3%) were reverted to sinus rhythm by piperazine. Again, 33% success was seen when ventricular fibrillation was induced. One of the three cases was reverted to the sinus rhythm as was also the only case of pulsus bigeminus observed. Piperazine, therefore, has the potential of a good anti-arrhythmic agent. Piperazine was shown to be a more effective antiarrhythmic agent than propranolol against BCinduced ventricular fibrillation. Propranolol not only failed to revert any of the ventricular fibrillations to sinus rhythm, but in two of four cases was not able to reverse the induced ventricular tachycardia. Although piperazine failed to control ventricular fibrillation with the same degree of effectiveness, piperazine has a remarkable therapeutic value in the management of ventricular tachycardia.

Keywords

Piperazine citrate, arrhythmias, electrocardiogram, rat

Introduction

Arrhythmia refers to disruption of normal sequence of electrical impulses causing abnormal heart rhythms. It is a potentially lethal cardiovascular condition. The incidence of ventricular arrhythmias is not well documented. Atrial fibrillation is the most commonly sustained of various kinds of cardiac arrhythmias [1]. It has a prevalence of six per cent in the population over 65 years of age [1]. Atrial flutter has an incidence of 88/100,000 persons per year and increases with age [2]. Patients over 80 years have been documented to have an incidence of 587/100,000 [2].

Anti-arrhythmic drugs act by either slowing conduction or lengthening the refractory period of cardiac tissue [3]. Arrhythmias have been induced with drugs or whole heart ischaemia [4-7] and the ability of a test drug to reverse the induced arrhythmia to sinus rhythm is taken as evidence of anti-arrhythmic effect.

Prompt management of arrhythmic conditions, especially ventricular arrhythmia, is imperative as a proportion of the population presenting with ventricular arrhythmias will be at high risk of sudden cardiac death [8]. Although a giant stride has been taken in understanding basic cardiac electrophysiology, many facts about arrhythmogenesis remain largely unknown. This has made treatment of various tachyarrhthmias an empirical trial often inadequate in preventing life threatening arrhythmias. This has necessitated the introduction of many anti-arrhythmia devices which include traditional pacing systems such as inhibited single and dual chamber pacemakers (AA1, VVl, DVl, and DDD) for the control of bradyarrhythmia and for overdrive suppression of certain tachyarrhythmia [9], radio-frequency ablation, and burst pacing systems and implantable cardioverters for control of both su-praventicular tachycardia and fibrillation [10,11], and synthesis of wide spectrum of drugs with varying electrophysiologic properties [12]. Many of these agents had been used for other ailments before serendipity, coupled with some good sense, necessitated their use as antiarrhythmic drugs. Quinidine for instance was first used as an antimalarial agent before Jean Baptiste de Senac [13] noted its anti-arrhythmic effect and lignocaine, a local anaesthetic, was discovered fortuitously during a cardiac surgery to have anti-arrhythmic properties [14]. The search for anti-arrhythmic drugs still continues, as each drug is associated with adverse effects some of which may be quite serious.

Recently, Onuaguluchi and Ghasi [15] showed that piperazine citrate treatment in human volunteers might be of some value in the management of dysrhythmic conditions. Furthermore, cardioprotective effect of piperazine in the rat has also been demonstrated [16]. Consequently, it was decided to study the effects of piperazine on BC-induced arrhythmias in the anaesthetized albino rat connected to an electrocardiographic machine. For comparative purposes, effects of propranolol, a standard anti-arrhythmic drug, were also evaluated in the same animal model.

The rat has been chosen as the animal model for this study as it withstands the rigors of cannulation more than most other animals, and has been used by many other investigators to determine the ECG changes due to various factors even though the rat has short QT intervals and no ST segment [17-23].

Material and Methods

Albino Wistar rats of either sex weighing between 200 and 250g were used. They were anaesthetized with thiopentone sodium (50mg/kg) intra-peritoneally and placed in a supine position with the four limbs tied to a dissecting board. A longitudinal incision about 1.5cm in length was made in the middle of the neck and the skin reflected laterally to expose one of the external jugular veins. The vein was dissected of fat and other tissues. Two cotton threads for ligature were then passed under the vein. A small incision was made on the vein between these ligatures. A polythene cannula filled with heparinized saline (10 i.u. of heparin per ml of normal saline) was inserted into the vein and secured in position with the inferior ligature. The superior ligature was used to occlude the vessel about the point of cannulation.

The animal was then connected to an electrocardiographic (ECG) machine (Bioscience 400 series Washington Oscillograph) by means of pin electrodes inserted subcutaneously into the right forelimb and left hind limb. ECG records were obtained on Lead II channel of the ECG machine. ECG recordings were obtained at a paper speed of 10mm per second.

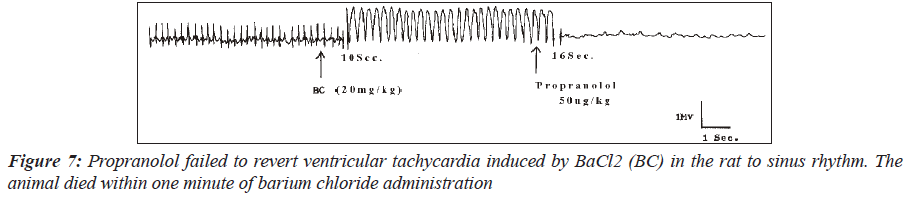

Singh et al. [24] had shown that BaCl2 of 3mg/kg i.v was adequate for the production of ventricular arrhythmia in dogs. However, in the present study it was found that the dosage between 12.5mg/kg and 15mg/kg of BaCl2 was required to induce ventricular tachycardia in the rat, which was sometimes found to induce ventricular fibrillation within 15 seconds. Therefore, cardiotoxicity response to BaCl2 would appear to show species variations. Because a consistent lethal dose was required for this study and BaCl2 at this dose range did not regularly produce ventricular fibrillation, a larger dose of BaCl2 was therefore employed. Ventricular fibrillation was induced by intravenous (jugular vein) administration of barium chloride (20 mg/kg). In all cases, the animals died within, if untreated, one minute of ventricular fibrillation.

To evaluate the anti-arrhythmic action of piperazine, ventricular dysrhythmia was established with BaCl2 (20mg/ kg) in 16 of the animals. The effect of piperazine (30 mg/ kg) on the BaCl2–induced arrhythmia was studied in 10 of the rats. Ability of the drug to revert the arrhythmia to sinus rhythm was taken as an indication of its anti-arrhythmic activity on the particular preparation. For comparative purposes, the anti-arrhythmic effect of propranolol (50mcg/ kg) on the BaCl2-induced arrhythmia in the rat was similarly undertaken in the remaining 6 rats.

Results

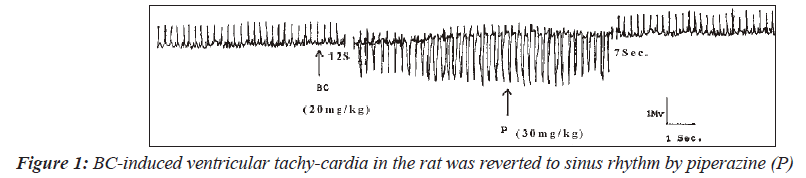

BaCl2 of 20mg/kg was used to induce arrhythmias in 21 Wistar rats of either sex. Five of the rats that were not treated with piperazine following BaCl administration died within one minute from ventricular fibrillation. Among the 10 rats with BaCl2-induced dysrhythmia, treated with piperazine, five of the six cases of ventricular tachycardia were successfully reverted to sinus rhythm. Figure 1 shows the electrocardiograms in which the BaCl2-induced ventricular tachycardia was reverted to sinus rhythm. Ventricular fibrillation was induced in another three rats.

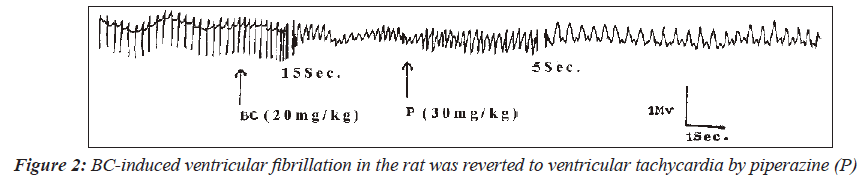

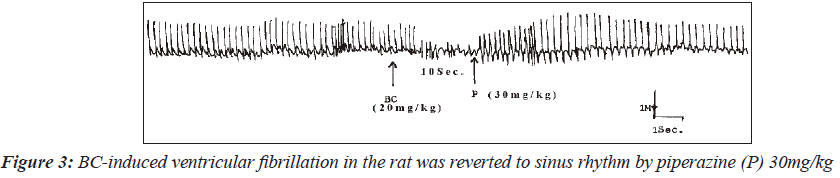

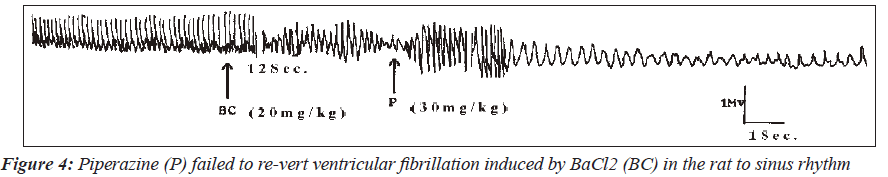

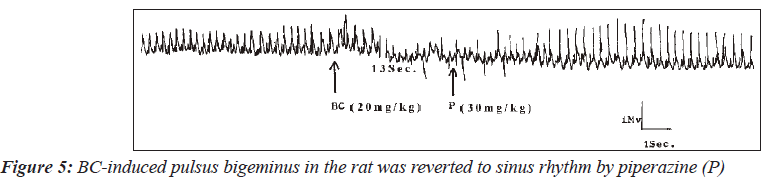

In one of the three animals, induced fibrillation was reverted to tachycardia (Figure 2). Interestingly, in one rat, piperazine reversed the BaCl2-induced fibrillation to sinus rhythm (Figure 3). However, piperazine at a dose of 30mg/kg failed to reverse the ventricular fibrillation induced in one of the rats to the sinus rhythm (Figure 4). The only case of pulsus bigeminus seen was reverted to sinus rhythm by piperazine (Figure 5).

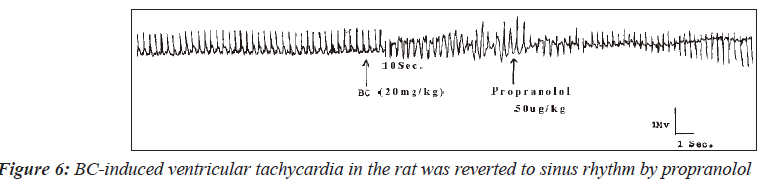

In another group of six rats with ventricular arrhythmias, propranolol at a dose of 50mcg/kg reversed two of the four cases of ventricular tachycardia to sinus rhythm. Figures 6 shows the electrocardiogram of one of the two rats where ventricular tachycardia was reverted to sinus rhythm while Figure 7 is an electrocardiogram showing inability of propranolol to revert barium chloride-induced ventricular tachycardia to sinus rhythm.

Discussion

The results of this study have shown that piperazine is a definite and potent antiarrhythmic agent. The drug has been shown to affect various forms of BC-induced ventricular arrhythmia. Five out of 6 cases of induced ventricular tachycardia (83.3%) were reverted to sinus rhythm by piperazine. Again, 33% success was seen when ventricular fibrillation was induced. One of the three cases was reverted to the sinus rhythm. Piperazine, therefore, has the potentials of a good anti-arrhythmic agent.

Barium is known to stimulate all muscles in the mammalia causing strong vasoconstriction, violent peristalsis, convulsive tremors, and increased excitability and force of contraction of the heart [25]. In terms of ionic fluxes, the effects of barium on the heart and other excitable membranes are largely attributable to the decline in the outward diffusion of K+ from the cell (that is, inhibition of the transient outward and delayed rectifier currents) without any decrease in the actively transported influx, that is, the inward rectifier protein [26]. The result is accumulation of K+ ions within the cells at the expense of extracellular K+. Actually, hypokalaemia is the main electrolyte disturbance in barium toxicity [25,27,28]. Indeed cardiac toxicity induced by Ba2+ has been successfully treated with potassium salt solution given intravenously [25,28,29]. This is because the most important concern regarding K+ depletion is its influence on ventricular fibrillation, which is the leading cause of sudden cardiac death and a major contributor to cardiovascular mortality [30]. Studies in experimental animals have demonstrated that K+ depletion lowers the threshold for electrically induced ventricular fibrillation in the ischaemic myocardium and also increases spontaneous ischaemic ventricular fibrillation [31,32]. The fact that Ba2+ is able to reactivate myocardial Na+-K+ATPase after depression by inhibitors of the enzyme such as ouabain in vitro [33], suggests that Ba2+ may in fact enhance active transport of K+ into the cell in vivo.

Piperazine is a direct non-specific, non-vascular smooth muscle relaxant. It has been shown to inhibit barium chloride, histamine, 5HT and acetylcholine-induced contractions in the guinea-pig ileum and rabbit duodenum [34-36]. It also antagonizes adrenaline-induced contraction of the guineapig vas deferens and oxytocin-induced contractions in the rat uterus [34,35].

The normal cardiac cell at rest maintains a trans-membrane potential approximately 80 to 90mV negative to the exterior. This gradient is established by pumps, especially Na+- K+ATPase, and fixed anionic charges within cells [30].

There is both an electrical and a concentration gradient that would move Na+ ions into resting cells. However, Na+ channels, which allow Na+ to move along this gradient, are closed at negative transmembrane potentials so Na+ does not enter normal resting cardiac cells until it is depolarised above a threshold potential. In contrast, a specific type of K+ channel protein (the inward rectifier protein) is in an open conformation at negative potentials [30].

Since BaCl2 does not have any negative effect on the potassium inward current and may indeed increase K+ influx at negative transmembrane potentials (increased phase 4 slope), it is understandable why BaCl2 elicits automaticity of the cardiac muscle.

From the foregoing discussion, piperazine has been shown to inhibit the effects of BaCl2. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that its predominant ionic effect is blocking the potassium channels.

Piperazine may, therefore bring about its anti-arrhythmic action by decreasing Ca2+ current, and inhibiting transient outward, delayed rectifier, and especially inward rectifier K+ currents since action potential duration may be influenced by several ion currents simultaneously [37]. It has also been established that transient outward and delayed rectifier currents actually result from multiple ion channel sub-types [38,39], and that acetylcholine-evoked hyperpolarization results from activation of a K+ by hetero-oligomerization of multiple, distinct channel proteins [40]. Piperazine may, therefore, be affecting any of these potassium ion channel sub-types. Incidentally, some piperazine derivatives have been shown to inhibit the potassium channels [41,42].

Potassium channel block would be expected to produce a series of desirable effects, such as, decreased automaticity, reduced defibrillation energy requirement, and inhibition of ventricular fibrillation due to acute ischaemia [43,44]. Furthermore, the increase in action potential duration because of the prolongation of the Q-T interval would increase refractoriness which should be an effective way of treating re-entry rhythm [45,46].

Beta-adrenoceptor agonists, like Ba2+, decrease the plasma concentration of K+ by promoting the uptake of the ion. Beta-blocking agent such as propranolol negates this buffering effect [47], and contributes to its anti-arrhythmic action. Similarly, piperazine may negate the arrhythmogenic effect of BaCl2 by blocking the K+ channels. Since most K+ channel blocking drugs also interact with beta-adrenergic receptors, such as sotolol that prolongs cardiac action potential by inhibiting K+ currents [48], and other channels (example, amiodarone), a multiple mechanism of action may equally be possible in the case of piperazine. Sotolol is more effective for many arrhythmias than other betablocking agents, probably because of its additional K+ channel-blocking actions [30].

It is, therefore, understandable why piperazine in this study proved to be a more effective antiarrhythmic agent than propranolol, as propranolol does not inhibit K+ currents. Propranolol not only failed to revert any of the ventricular fibrillations to sinus rhythm but in two instances it was not able to reverse the induced ventricular tachycardia to the sinus rhythm. Piperazine, on the other hand, was successful in reverting five of the six cases of BaCl2– induced ventricular tachycardia to sinus rhythm.

The therapeutic value of piperazine in the management of ventricular tachycardia was very excellent. It, however failed to manage ventricular fibrillation with the same measure of success. It is, however, interesting to witness any success at all as ventricular fibrillation is a rare phenomenon usually observed by a very few physicians who have by chance recorded the incident at the time of death. The patients were best treated not with drugs but with DCcardioversion, the application of a large electric current across the chest [30]. Therefore, piperazine should have its proper place as an antiarrhyhmic drug, since it is affordable and is well tolerated with minimal adverse effects.

References

- Feinberg WM, Blackshear JL, Laupacis A, Kronmal R, Hart RG. Prevalence, age distribution and gender of patients with atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med 1995;155:469-73.

- Granada J, Uribe W, Chyou PH, Maassen K, Vierkant R, Smith PN, et al. Incidence and predictors of atrial flutter in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:2242-6.

- Schilling RJ. Which patient should be referred to an electrophysiologist: Supraventricular tachycardia. Heart 2002;87:299-304.

- Onuaguluchi G, Igbo IN. Comparative antiarrhythmic and local anaesthetic effects of piperazine citrate and lignocaine hydrochloride. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Therap 1985;274:253-66.

- Lu HR, Yang P, Remeysen P, Saels A, Dai DZ, De Clerck F. Ischaemia/reperfusion induced arrhythmias in anaesthetized rats: a role of Na+ and Ca2+ influx. Eur J Pharmacol 1999;365:233-9.

- Zhu P, Lu L, Xu Y, Schwartz GG. Troglitazone improves recovery of left ventricular function after regional ischaemia in pigs. Circulation 2000;101:1165-71.

- Ansawa R, Seki S, Horikoshi K, Taniguchi M, Mochizuki S. Exacerbation of acidosis during ischaemia and reperfusion arrhythmia in hearts from type 2 diabetic Otsuka Long-Evans TokushimaFatty rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2007;6:17.

- Morgan JM. Patients with ventricular arrhythmias: Who should be referred to an electrophysiologist? Heart 2002;88:544-50.

- Parsonnet V, Berstein AD. Cardiac pacing in the 1980s: Treatment and techniques in transition. JACC 1983;1:339–54.

- Winkle RA, Bach SM Jr, Echt DS, Swerdlow CD, Imran M, Mason JW, et al. The automatic implantabledefibrillation: Local ventricular bipolar sensing to detect ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation. Am J Cardiol

- 1983;52:265–70.

- Morady F. Radio-frequency ablation as treatment for cardiac arrhythmias. N Engl J Med 1999;340:534-44.

- Vaughan Williams EM. A Classification of antiarrhythmic action reassessed after a decade of new drugs. J Clin Pharmacol 1984;24:129-47.

- Bigger JT, Hoffman BF. Antiarrhythmic drugs. In: Gil-man AG, Rall TW, Nies AS, Taylor P, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. Vol. 1. 8th (International) ed. Pergamon Press; 1980. p. 840-70.

- Harrison DC, Sprouse JH, Morrow AG. The antiarrhythmic properties of lidocaine and procainamide- Clinical and physiologic studies of their cardiovascular effects in man. Circulation 1963;28:486-91.

- Onuaguluchi G, Ghasi S. Electrocardiographic profile of oral piperazine citrate in healthy volunteers. Am J Ther 2006;13:43-7.

- Ghasi S. Piperazine protects the rat heart against sudden cardiac death from barium chloride-induced ventricular fibrillation. Am J Ther 2008;15:119-25.

- Kharidia J, Eddington ND. Effects of desethyloamiodarone on the electrocardiogram in conscious freely moving animals: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modelling using computer-assisted radio telemetry. Biopharm Drug Dispos 1996;17:93-106.

- Sgoifo A, de Boer SF, Westenbroek C, Maes FW, Beldhuis H, Suzuki T, et al. Incidence of arrhythmias and heart rate variability in wild-type rats exposed to social stress. Am J Physiol 1997;273:H1754-60.

- Akita M, Kuwahara M, Tsubone H, Sugano S. ECG changes during furosemide-induced hypokalemia in the rat. J Electrocardiol 1998;31:45-9.

- Sgoifo A, De Boer SF, Buwalda B, Korte-Bouws G, Tuma J, Bohus B, et al. Vulnerability to arrhythmias during social stress in rats with different sympathovagal balance. Am J Physiol 1998;275:H460-6.

- Watkinson WP, Campen MJ, Costa DL. Cardiac arrhythmia inductionafter exposure to residual oil fly ash particles in a rodent model of pulmonary hypertension. Toxicol Sci 1998;41:209-16.

- Aberra A, Komukai K, Howarth FC, Orchard CH. The effect of acidosis on the rat heart. Exp Physiol 2001;86:27-31.

- Matthew CB, Bastille AM, Gonzalez RR, Sils IV. Heart rate variability and electrocardiogram waveform as predictors of morbidity during hypothermia and rewarming in rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 2002;80:925-33.

- Singh KP, Pendse VK, Bhandari DS. Cyproheptadine in ventricular arrhythmias. Indian Heart J 1975;27:120-8.

- Roza O, Berman LB. The pathophysiology of barium hypokalaemic and cardiovascular effects. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1971;177:433-9.

- Sperelakis N, Schneider MF, Harris EJ. Decrease in K+ conductance produced by Ba2+ in frog sartorious fibres.J Gen Physiol 1967;50:1565-83.

- Peach MJ. Cation: Calcium, magnesium, barium, lithium, and ammonium. In: Goodman LS, Gilman A, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 5th ed. Macmillan; 1975. p. 782-95.

- Dreisbach RH. Miscellaneous pesticides. In: Hand-book of poisoning. Lange Medical Publications; 1980. 29. Gould DB, Sorrel MR, Luparielo AD. Barium sulphidepoisoning: some factors contributing to survival. Archives of Internal Medicine 1973;1321:891-4.

- Roden DM. Antiarrhythmic Drugs. In: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 10th ed. Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Gilman AG, editors. McGraw Hill, Medical Publishing Division; 2001. p. 933-70.

- Curtis MJ, Hearse DJ. Ischaemia-induced and reperfusioninduced arrhythmia differ in their sensitivity to potassium: implications for mechanisms of initiation and maintenance of ventricular fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1989;21:21-40.

- Yano K, Hirata M, Matsumoto Y, Hano O, Mori M, Ahmed R. et al. Effects of chronic hypokalaemia on ventricular vulnerability during acute myocardial ischaemia in the dog. Japanese Heart Journal 1989;30:205-17.

- Henn FA, Sperelakis N. Stimulative and protective action of Sr2+ and Ba2+ on (Na+- K+) ATPase from cultured heart cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1968;163:415-7.

- Onuaguluchi G. Some aspects of the pharmacology of piperazine citrate and the antiascaris fraction of the ethanolic extract of the bark of ERIN tree (Polyadoa umbellate- Dalziel). West Afr Med J 1966;15:22-5.

- Onuaguluchi G. Effect of the antiascaris fraction of the ethanolic extract of the bark of Polyadoa unbellata (ERIN) and of piperazine citrate on mammalian non-vascular smooth muscle. The Pharmacologist 1981;23:45.

- Onuaguluchi G. Effect of piperazine citrate and of the antiascaris fraction of the bark of Polyadoa umbellate (ERIN) on mammalian non-vascular smooth muscle. Arch Int Pharmacodyn 1984;269:263-70.

- Bányász T, Magyar J, Szentandrássy N, Horváth B, Birinyi P, Szentmiklósi J, et al. Action po-tential clamp fingerprints of K+ currents in canine cardiomyocytes: their role in ventricular repolarization. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;190:189-98.

- Tseng GN, Hoffman BF. Two components of transient outward current in canine ventricular myocytes. Circ Res 1989;308:1436-42.

- Sanguinetti MC, Jurkiewicz NK. Two components of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current: differential sensitivity to block by class III antiarrhythmic agents. J Gen Physiol 1990;96:195-215.

- Krapivinsky G, Gordon EA, Wickman K, Velimirovic B, Krapivinsky L, Clapham DE. The G protein-gated atrial K+ channel is a heteromultimer of two inwardly rectifying K+ channel proteins. Nature 1995;374:135-41.

- Furukawa Y, Akahane K, Ogiwara Y, Chiba S. K+ channel blocking and antimuscarinic effects of a novel piperazine derivative INO2628, on the isolated dog atrium. Eur J Pharmacol 1991;193:217-22.

- Habuchi Y, Tanaka H, Furukawa T, Tsujimura Y, Takahashi H, Yoshimura M. Endothelin enhances delayed potassium current via phospholipase C in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol 1992;262:H345-54.

- Echt DS, Black JN, Barbey JT. Coxe DR, Cato E. Evaluation of antiarrhythmic drugs on defibrillation energy requirements in dogs: Sodium channel block and action potential prolongation. Circulation 1989;79:1106-17.

- Roden DM. Current status of class III antiarrhythmic drug therapy. American Journal of Cardiology 1993;72:44B-9B.

- Task Force of the Working Group on Arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology, The Sicilian Gambit: A new approach to the classification of antiarrhythmic drugs based on their actions on arrhythmogenic mechanisms. Circulation 1991;84:1831-51.

- Singh BN. Arrhythmia control by prolonging repolarization: the concept and its potential therapeutic impact. Eur Heart J 1993;14:14-23.

- Brown MJ. Hypokalaemia from beta2-receptor stimulation by circulating epinephrine. Am J Cardiol 1985;56:3D-9D.

- Hohnloser SH, Woosley RL. Sotalol. N Engl J Med 1994;331:31–8.