Case Report - Current Pediatric Research (2024) Volume 28, Issue 9

Identifying the clinical phenotypes of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome: A case study

Issell Nicolle Aguirre1*, Jose Angel Cruz Estrada2

1Department of Paediatrics, National Autonomous University of Honduras, Tegucigalpa, Honduras

2Department of Paediatrics, Central American Technological University UNITEC, Tegucigalpa, Honduras

- Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Issell Nicolle Aguirre

Department of Paediatrics,

National Autonomous University of Honduras,

Tegucigalpa,

Honduras

E-mail: praga776@gmail.com

Received: 28 July 2020, Manuscript No. AAJCP-24-16338; Editor assigned: 31 July, 2020, Pre QC No. AAJCP-24-16338 (PQ); Reviewed: 14 August, 2020, QC No. AAJCP-24-16338; Revised: 01 September, 2024, Manuscript No. AAJCP-24-16338 (R); Published: 29 September, 2024, DOI: 10.35841/0971-9032.28.09.2355-2358.

Abstract

The wide range of genetic diseases usually have clinical manifestations at a structural and neurodevelopment level, this also apply to the Cornelia de Lange Syndrome which is associated to divers errors on the genetic structures of NIPBL, SMC1A, SMC3, RAD21, HDAC8. This genes regulate cohesin which takes an important rol in chromatin fusion. The Cornelia de Lange Syndrome has different phenotypic characteristics clinically speaking, including growth restriction, variable cognitive deficit, upper extremity malformations and distinct characteristics on cranial bone and face which can help to make an early clinical diagnostic. Here a 2 month old girl is presented who had a low weight at birth of 1320 gr and various phenotypic craneofacial and extremity malformations compatible with Cornelia de Lange Syndrome.

Keywords

Cornelia de Lange Syndrome, Synophrys, Dismorphism.

Introduction

Cornelia de Lange Syndrome (CdLS) is a rare genetic disorder with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations affecting multiple organ systems, including craniofacial anomalies, limb malformations, growth retardation and neurodevelopmental delay. First described in 1933, CdLS has an estimated prevalence of 0.5 to 1 per 10,000 live births, yet it remains underreported in many regions, including Honduras, where only two cases have been documented in the literature. This autosomal dominant disorder is primarily caused by mutations in genes involved in the cohesin complex, such as NIPBL, SMC1A and RAD21, which regulate chromosomal segregation and gene expression. The phenotypic presentation ranges from mild to severe, often making early diagnosis challenging without comprehensive clinical expertise or genetic testing [1].

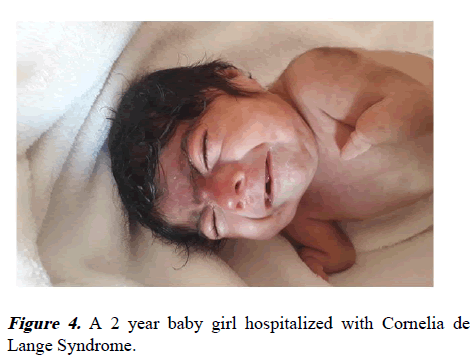

In this report, we describe a two-month-old female infant from Honduras presenting with a constellation of clinical features consistent with classic CdLS. The patient exhibited severe Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR), craniofacial dysmorphisms, limb anomalies and multi-organ involvement, aligning with the established diagnostic criteria for CdLS. Despite the lack of genetic testing, the clinical findings provide sufficient evidence to identify CdLS and emphasize the importance of clinical recognition in resource-limited settings.

This case highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of managing CdLS, underscores the need for interdisciplinary care and adds to the growing body of literature on CdLS in underserved populations [2].

Case Presentation

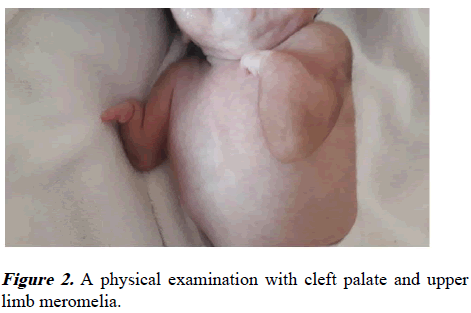

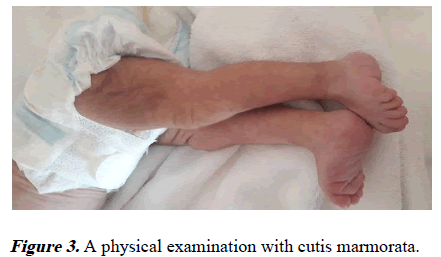

We describe a 2-month-old baby girl, the second child to a nonconsanguineous couple from Honduras. At her birth, the mother was 31 years old with no history of teratogenic exposures and no comobirdities before or during pregnancy. At birth with intrauterine growth restriction and very low weight of 1320 gr (<3 percentile), length 36 cm (<3 percentile), with microcephaly with an OFC of 27.5 cm (<3 percentile). At physical examination with synophrys, generalized hypertricosis and depressed nasal bridge, cleft palate, upper limb meromelia and cutis marmorata. At birth she was hospitalized like Cornelia de Lange Syndrome because of her clinical characteristics and it was found left cystic kidney, left ureteral stenosis, ependemmary cyst and a ventricular septal defect. Unfortunately we do not have a genetical evaluation but the clinical findings can orient any physician to make the diagnosis (Figures 1-4) [3].

Results and Discussion

Cornelia de Lange Syndrome is a dominantly inherited disorder characterized by abnormalities in the upper limbs, hirsutism, growth and cognitive retardation. It is a heterogeneous disorder that shows a wide phenotypic range [4].

The prevalence described is 0.5-1/10.000 live births, in our research we found two clincal cases published in Honduras.

Clinical features

There are three phenotypes described by Gillis in 2004 with a wide spectrum. This classification is based in three physical characteristics: The level of limb reduction, the developmental and cognitive habilities and the growth percentile that can be from mild to severe affectation [5].

The syndrome has a broad spectrum from mild to severe clinical features, where almost every organ system can be affected. The most common involved are neurodevelopmental, craniofacial, gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal systems in Table 1 we describe the most common features by systems [6].

| Clinical features | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Craniofacial features | Microcephaly |

| Low hair implantation | |

| Low ear implantation | |

| Synophrys | |

| Long eyelashes | |

| Anteverted nostrils | |

| Fine lips | |

| Elongated filtrum | |

| Retromicrognathia | |

| Growth and nutrition | Intrauterine growth restriction |

| Posnatal growth retardation | |

| CNS | Cognitive delay |

| Musculoskeletal | Severes: Amelia, phocomelia, meromelia oligodactyly |

| Mild: Clinodactily, sindactily, short fifth finger | |

| Others | Hypertrichosis |

| Cutis marmorata 60% |

Table 1. Common clinical features in Cornelia de Lange Syndrome.

In our patient almost all this characteristic were present including other such as cardiac defects.

Diagnosis

Phenotypically the classic Cornelia de Lange Syndrome has clinical characteristics that make it easy to identify by qualified personnel, clinically it stands out for different craniofacial malformations accompanied by shortened upper extremities and with birth weight below the 5th percentile [7].

In 2018 a group of international experts, established an international Cornelia de Lange Syndrome consensus group, they classified several features described as: 6 cardinal signs (2 pts each), 7 suggestive signs (1 pts each), whereas if the score is greater than or equal to 11, it is considered a classic phenotype, 9-10 is considered a non-classical phenotype, 4-8 of which 1 is a cardinal sign, genetic tests must be indicated and less than 4 does not indicate genetic tests [8].

Prenatal diagnosis have a greater degree of difficulty, with intrauterine growth failure being one of the main characteristics, where the literature reports cephalic and abdominal fetal circumference that falls below the 10th percentile, in the third trimester [9].

In the ultrasound we can find an interesting tool, though it's findings will depend on the degree of severity with which Cornelia de Lange Syndrome occurs, where the observational is usually clinodactyly, monodactyly or complete absence of the upper limb. The easy characteristics can be suggestive. Other malformations can also be identified, such as: diaphragmatic hernia, heart disease. In conclusion, there is no relationship between alterations in amniotic fluid volume and Cornelia de Lange Syndrome [10].

For the right therapeutic guideline, interdisciplinary attention is required with otorhinolaryngologists, neurologists, psychology, gastroenterologist and surgery, who must annually monitor psychomotor development. Growth and assess heart and kidney function.

Conclusion

This case of a two-month-old infant with Cornelia de Lange Syndrome exemplifies the diagnostic complexities and multisystem involvement characteristic of this rare genetic disorder. The patient's clinical presentation, marked by significant craniofacial anomalies, upper limb malformations, growth retardation and associated cardiac and renal abnormalities, aligns with the classical phenotype of CdLS. Although genetic testing was unavailable in this case, the constellation of clinical features underscores the critical role of thorough physical examination and clinical acumen in diagnosing CdLS, especially in low-resource settings. This case also highlights the importance of interdisciplinary management, including genetic counseling, neurologic evaluation and monitoring of growth and organ function. Early recognition and coordinated care are essential to optimize developmental outcomes and address the complex needs of individuals with CdLS. Furthermore, prenatal detection of key features such as IUGR and limb abnormalities via ultrasonography could enhance early diagnosis and parental counseling in future cases. By documenting this case, we aim to increase awareness of CdLS within the medical community, particularly in regions where it is infrequently reported. Further studies and collaborations are necessary to better understand the epidemiology, clinical spectrum and genetic basis of CdLS in diverse populations, ensuring timely diagnosis and access to specialized care for affected individuals.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Krantz ID, McCallum J, de Scipio C, et al. Cornelia de Lange Syndrome is caused by mutations in NIPBL, the human homolog of Drosophila melanogaster Nipped-B. Nat Genet 2004; 36: 631-635.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Basel‐Vanagaite L, Wolf L, Orin M, et al. Recognition of the Cornelia de Lange Syndrome phenotype with facial dysmorphology novel analysis. Clin Genet 2016; 89: 557-563.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kline AD, Krantz ID, Sommer A, et al. Cornelia de Lange Syndrome: Clinical review, diagnostic and scoring systems and anticipatory guidance. Am J Med Genet 2007; 143A: 1287-1296.

- Rodriguez P, Asturias K. A 16‐day‐old infant with a clinical diagnosis of classical Cornelia de Lange Syndrome. Case Rep Pediatr 2020; 2020: 6482938.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kline AD, Moss JF, Selicorni A, et al. Diagnosis and management of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome: First international consensus statement. Nat Rev Genet 2018; 19: 649-666.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avagliano L, Bulfamante GP, Massa V. Cornelia de Lange Syndrome: To diagnose or not to diagnose in utero? Birth Defects Res 2017; 109: 771-777.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oliver C, Arron K, Sloneem J, et al. Behavioural phenotype of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome: Case-control study. Br J Psychiatry 2008; 193: 466-470.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kline AD, Moss JF, Selicorni A, et al. Diagnosis and management of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome: First international consensus statement. Nat Rev Genet 2018; 19: 649-666.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Basel-Vanagaite L, Wolf L, Orin M, et al. Recognition of the Cornelia de Lange Syndrome phenotype with facial dysmorphology novel analysis. Clin Genet 2016; 89: 557-563.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilmink FA, Papatsonis DN, Grijseels EW, et al. Cornelia de Lange Syndrome: A recognizable fetal phenotype. Fetal Diagn Ther 2009; 26: 50-53.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]