Case Report - Current Pediatric Research (2017) Volume 21, Issue 3

Giant acquired tracheocele in a syndromic child: Case report and review of the literature.

Molinaro F1, Loglisci M2, Cocca S2, Monciatti G2, Pellegrino C1, Di Maggio G1, Angotti R1, Livi W2, Messina M11Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience, Pediatric Surgery, University of Siena, Siena, Italy.

2Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience, ENT, University of Siena, Viale Bracci, Siena, Italy.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Michele Loglisci

Department of Medicine, Surgery and Neuroscience

ENT, University of Siena, Viale Bracci

14, 53100, Siena, Italy.

Tel: +393274382601

Fax: +39 0577585470

E-mail: mik.loglisci@hotmail.it

Accepted date: May 19, 2017

Abstract

We report a case of acquired tracheocele in a child with multiple congenital anomalies of the face, limbs, kidneys, and heart, to share our experience with international scientific community, considering the rarity of the disease especially in the pediatric population. Patient’s history reported a tracheotomy at one month of life that was closed at 3 years old. Ten years later, the patient come to us for an anterior cervical mass swelling during respiratory effort and chronic productive cough. The diagnosis was made by high resolution Computed Tomography scan of the neck and chest and an elective surgical resection of the lesion under general anesthesia was done.

Keywords

Neck swelling, Tracheocele, Tracheostomy.

Introduction

Tracheocele is an uncommon air-filled mucosal diverticulum of the posterior membranous trachea. This cystic lesion contains air or a mixture of air and liquid.

Tracheocele usually occurs at the junction of the cartilaginous and membranous portion of the trachea, commonly on the right side because there is no posterior support from the esophagus [1-4].

Fewer than 30 cases have been reported in literature [5- 9]; especially as complication of tracheostomy’s closure [10-15]. We report a rare case of giant tracheocele in a patient with complex syndrome to share our experience with international scientific community [16-20].

Case Report

A 13 year old male was admitted at our Emergency Department for an anterior cervical mass swelling during respiratory effort and chronic productive cough.

Patient’s history reported a tracheotomy at one month of life for the difficult removal of tracheal tube that has been placed at birth for perinatal hypossia. Tracheotomy was closed at 3 years. Patient is affected from complex syndrome that includes many malformations (cleft palate, solitary kidney, patent ductus Botallo, situs inversus intestinal, congenital hip dysplasia, hypospadias, inguinal hernia). Genetic analysis confirmed chromosomal anomaly with unbalanced translocation of chromosomes 2 and 16. The analysis of the parents' karyotype was negative.

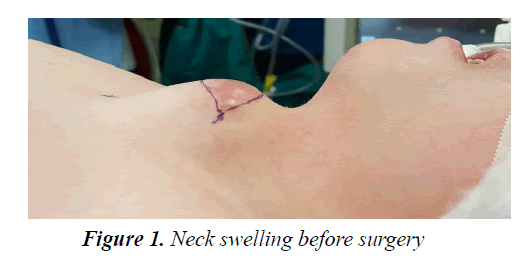

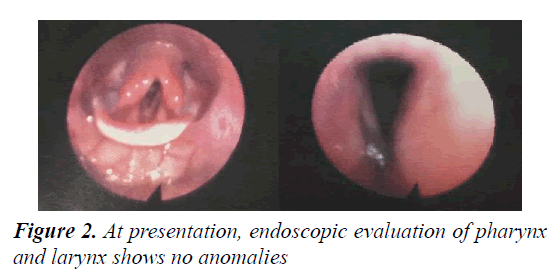

The examination of the neck revealed a soft compressible, non-pulsatile, transilluminant, 48 × 46 mm swelling over the previous tracheostomy scar (Figure 1). Further examination with flexible fiberoptic endoscope, showed absence of anomalies in the laryngeal district (Figure 2). Flexible bronchoscopy revealed a mild bulge of the anterior tracheal wall but no definite opening was identified: on exerting pressure on the neck, we found bubbles emanating approximately 30 mm from the vocal folds. There was no segmental malacia of tracheal wall.

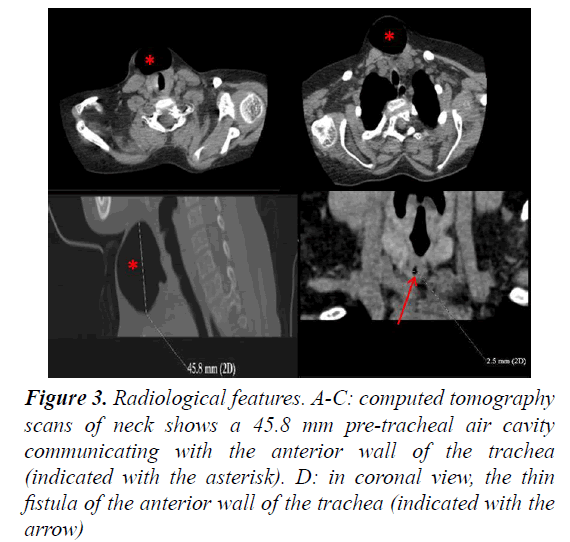

The diagnosis of acquired tracheocele was done by high resolution Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the neck and chest (Figure 3). It revealed a large, air-filled cavity, located on the anterior tracheal wall (40 × 48 × 46 mm diameter), with a small communication at primitive tracheostomy site (second tracheal ring).

Surgical Technique

We performed an elective surgical resection of the lesion under general anesthesia.

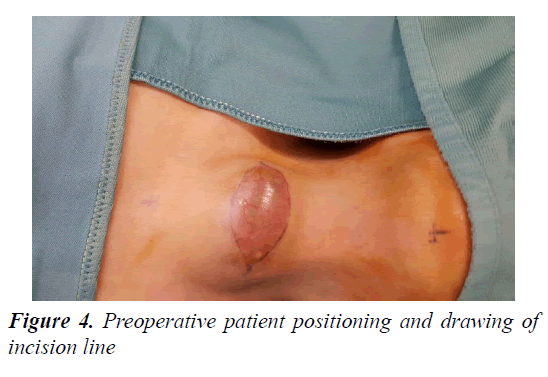

Patient positioning is obtained as in Figure 4. We performed a losange 55 mm incision at previous scar of tracheotomy below the tracheocele (Figure 4).

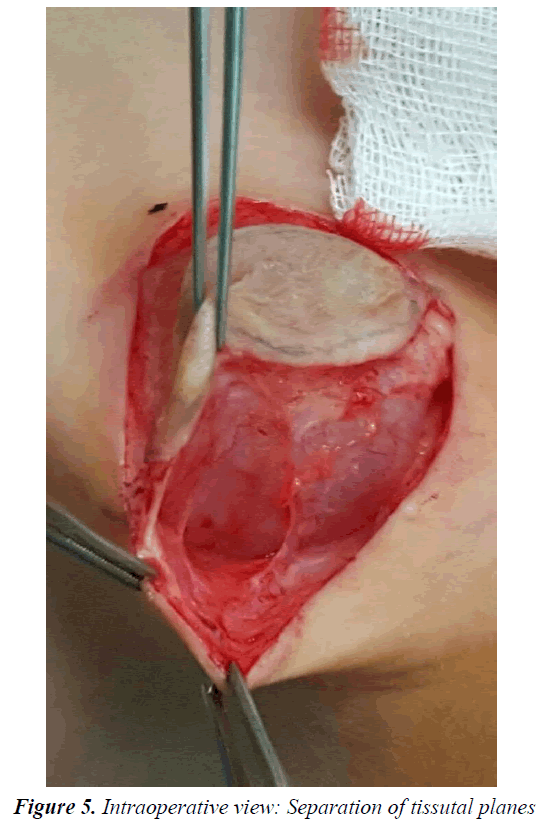

After subplatysmal dissection, sterno-hyoid muscle and sterno-thyroid muscle were cut. Isolation of the tracheocele was obtained by simple separation of tissutal planes without cutting the surrounding structures (Figure 5).

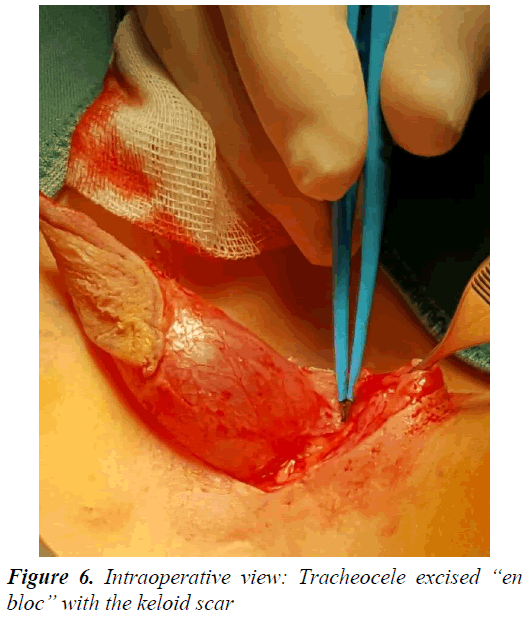

Removal of tracheocele was done “en bloc” with the keloid scar (Figure 6).

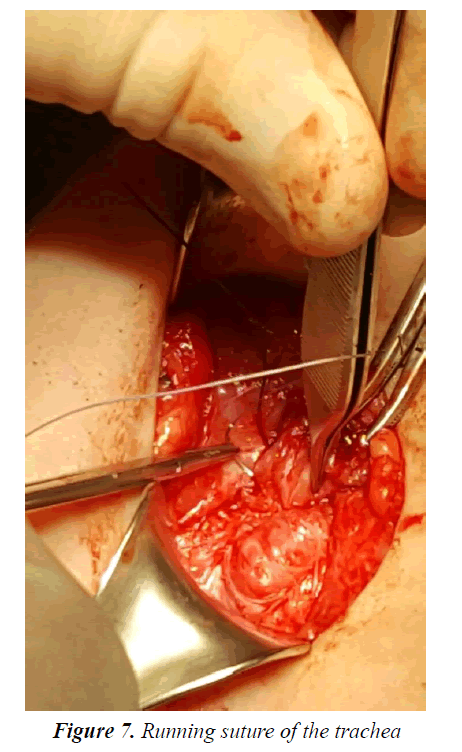

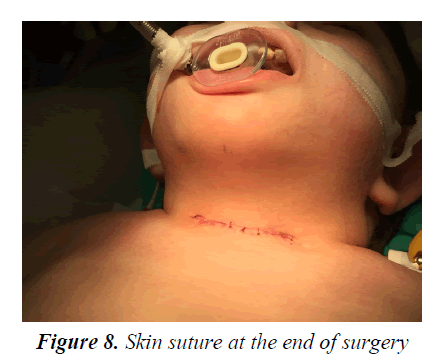

The fenestration of the trachea was closed by running suture (Figure 7). The skin was sutured with 3-0 Vycril and reinforced with pre-thyroid muscles to provide support (Figure 8).

Postoperative antibiotic therapy (ceftazidime 25 mg/kg 8 h intravenous) was given for 5 days. There were no postoperative complications. Histopathology report confirmed tracheocele (respiratory epithelium with chronic inflammation).

The patient was discharged in 5th postoperative day. We saw child in clinic after 3 months, he is in healthy and actually had no sign of recurrence.

Discussion

Tracheocele was first described by Rokitansky in 1846 [5]. Its prevalence is about 1% at postmortem examination and 0.3% at bronchoscopy evaluation of children older than 10 years [7]. Tracheocele can be classified as congenital and acquired: the structure is completely covered with respiratory epithelium and has no smooth muscle and/or cartilage in relation to its etiopathogenesis [8].

A congenital tracheocele arises from tracheal wall because of an embryonic anomaly with a predilection for males [9]. It may be often associated with laryngo-tracheo-esophageal anomalies and can remains dormant until adulthood [6,10,11].

An acquired tracheocele usually appears as a single pouch arising at the junction between the extrathoracic and intrathoracic parts of the trachea [12-15]. Esophageal or tracheal surgery (for example tracheotomy, repair of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula) [2,3,16,17], orotracheal intubation [18], trauma to trachea, chronic/recurrent bronchopulmonary diseases and increased intraluminal pressure have been suggested to explain the etiopathogenesis of tracheocele. In particular, chronic cough or increased inspiratory effort increase intraluminal pressure and this can induce mucosal herniation of weak areas of the tracheal wall [3,8,12,19-21].

Acquired tracheocele is an uncommon disease and is even rarer in pediatric age. Only two pediatric cases are reported in Literature (Table 1) [2,7].

| Title | Authors | Year | Case description | Therapy | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giant tracheocele following primary tracheostomy closure in a 3 year old child2 | Briganti et al. [2] | 2004 | 3 year old female Acquired tracheocele after tracheostomy | Tracheocele was completely dissected, and its small communication was closed | Broncoscopy at 14 months demonstrated a patent airway |

| Endoscopic treatment of tracheocele in pediatric patients7 | Berlucchi et al. [7] | 2010 | 7 year old male Acquired tracheocele after tracheoesophageal surgery | Endoscopic brushing of the tracheocele+application of fibrin glue into the pouch | No recurrence after two months |

| Giant acquired tracheocele in a syndromic child: case report and review of the literature. | Molinaro et al. [16,17] | 2016 | 13 year old-male with tracheotomy at one month of life for the difficult removal of tracheal tube. Tracheotomy was closed at 3 years | Elective surgical resection of the lesion under general anesthesia | No signs of recurrence after 3 months |

Table 1. Summary of the articles in the international literature (pediatric cases)

The first one describes a 3 year old female with an acquired tracheocele arising after simple surgical closure of tracheostomy. In this case, the diagnosis was made by TC scan and flexible bronchoscope which revealed a segmental tracheomalacia. Tracheocele was removed by surgery and broncoscopy at 14 months demonstrated a patent airway and no recurrence.

The second one is about a 7 year old male with acquired tracheocele after tracheoesophageal surgery.

A tracheobronchoscopy was performed and revealed a blind-ending pouch of the trachea. The therapy consisted in an endoscopic brushing of the tracheocele and application of fibrin glue into the pouch. A tracheal endoscopic examination revealed no recurrence after two months.

Our patient has history of tracheostomy at birth with difficulties of closure. However tracheocele showed after 10 years from tracheostomy removal. We suppose that recurrent pulmonary infections and chronic cough are causes of tracheocele in the site of previous tracheostomy. It is known, indeed, that surgery on trachea can expose patient to develop tracheocele.

The clinical presentation of tracheocele usually involves: dyspnea, dysphonia, hemoptysis, laryngeal stridor, apnea, neck pain, dysphagia [22]. Sometimes it can cause problems with orotracheal intubation or ventilation during a general anesthesia, or it can present as pneumomediastinum in case of rupture [23]. However, sometimes, as in our case, it is asymptomatic, as a cervical mass, that swells during respiratory effort.

Tracheobronchoscopy and CT scan are the gold standard exams to diagnose this disorder. Flexible fiberoptic endoscopy is useful to rule out the possibility of laryngocele, which may present with similar symptoms. CT assesses exact location, size and wall thickness of tracheocele and determines the nature of it (congenital or acquired) due to the presence or absence of cartilaginous rings in the diverticulum wall [7]. A barium esophagram is useful to exclude a possible fistula with esophagus and can show a fistula with the esophagus.

Differential diagnosis includes laryngeal and pharyngeal anomalies [6,10,11], apical paraseptal bullae [8], cervical hernia of the lung, intrathyroidal tumor or thyroid goiter, thyroglossal duct cyst, bronchogenic cyst, Zenker diverticulum, cystic hygroma, fasciitis [24], neoplasms.

Treatment of these lesions is usually conservative [8,19]. Surgical excision may be required if there is an airway compromise, recurrent respiratory infections or esthetic reasons [25].

In our case the choice to perform surgery was based on the presence of recurrent respiratory and local infections.

Conclusion

Acquired tracheocele is a rare disease in a pediatric age. Recurrent infections of the lower respiratory tract in children who previously underwent to trachea’s surgery, as in our case, must be considered a risk factor to develop a tracheocele. However, we can’t exclude that it is a correlation between giant tracheocele of child and his complex syndrome. This should justify, the late presentation of pathology from surgery of trachea.

References

- Nerurkar N, Patil P, Tampi S, et al. Tracheocele - A case report. Laryngoscope 2011; 121: 1735-1737.

- Briganti V, Tavormina P, Testa A, et al. Giant tracheocele following primary tracheostomy closure in a 3 year old child. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2004; 3: 411-412.

- Quiroga J, Rivo E, Moldes M. Aquired tracheocele 7 years after tracheostomy closure. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2013; 21: 99.

- Ramandass T, Rayappa C, Santosham R, et al. Tracheocele presenting with intermittent dysphonia: A case report. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015; 67: 141-144.

- Rokitansky K. Handbuk der Pathologischen Anatomie. Vienna. Edited Braunmuller and Seidel 1846; 3: 6-11.

- Early EK, Bothwell MR. Congenital tracheal diverticulum. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2002; 127: 119-121.

- Berlucchi M, Pedruzzi B, Padoan R, et al. Endoscopic treatment of tracheocele in pediatric patients. Am J Otolaryngol 2010; 31: 272-275.

- Soto-Hurtado EJ, Penuela-Ruiz L, Rivera-Sanchez I, et al. Tracheal diverticulum: A review of the literature. Lung 2006; 184: 303-307.

- Madana J, Yolmo D, Saxena SK, Gopalakrishnan S. Giant tracheocele with multiple congenital anomalies. Ear Nose Throat J 2012; 91: E13-15.

- Varetti C, Giannotti G, Meucci D, et al. Neonatal laryngeal saccular cyst: A case report. Chirurgia. 2010; 23: 21-23.

- Sivaraman A, Jaikaran GK, Sashank RK. Tracheocele masquerading as foregut duplication cyst in the neck. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2011; 40: 274.

- Infante M, Mattavelli F, Valente M, et al. Tracheal diverticulum: A rare cause and consequence of chronic cough. Eur J Surg 1994; 160: 315-316.

- Endo S, Saito N, Hasegawa T, et al. Tracheocele: Surgical and thoracoscopic findings. Ann Thorac Surg 2005; 79: 686-687.

- Shah RN, Parikh SL, Johns MM. 3rd edn. Radiology quiz case 1. Diagnosis: Tracheocele. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007; 133: 724-726.

- Goldman L, Wilson JG. Tracheal diverticulosis. AMA Arch Otolaryngol 1957; 65: 504-507.

- Molinaro F, Garzi A, Cerchia E, et al. Sternal reconstruction by extracellular matrix: A rare case of phaces syndrome. Open Med (Wars) 2016; 11: 196-199.

- Molinaro F, Angotti R, Garzi A, et al. Prenatal diagnosis, 3-D virtual rendering and lung sparing surgery by ligasure device in a baby with "cCAM and intralobar pulmonary sequestration". Open Med (Wars) 2016; 11: 200-203.

- Davies R. Difficult tracheal intubation secondary to a tracheal diverticulum and a 90 degree deviation in the trachea. Anaesthesia 2000; 55: 923-925.

- Razak A, Patil PH, Sahota JS, et al. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010; 139: e27-28.

- Henderson CG, Harrington RL, Izenberg S, et al. Tracheocele after routine tracheostomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995; 113: 489-490.

- Passali D, Gregori D, Lorenzoni G, et al. Foreign body injuries in children: A review. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2015; 35: 265-271.

- Alt JA, Vaysberg M, Chheda NN. Tracheocele: An unusual cause of dysphonia. Laryngoscope 2010; 120: S193.

- Möller GM, ten Berge EJ, Stassen CM. Tracheocele: A rare cause of difficult endotracheal intubation and subsequent pneumomediastinum. Eur Respir J 1994; 7: 1376-1377.

- Lorenzini G, Picciotti M, Di Vece L, et al. Cervical necrotizing fasciitis of odontogenic origin involving the temporal region--a case report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2011; 39: 570-573.

- Porubsky EA, Gourin CG. Surgical treatment of acquired tracheocele. Ear Nose Throat J 2006; 85: 386-387.