Research Article - Biomedical Research (2017) Volume 28, Issue 9

Factors influencing relapse in schizophrenia: A longitudinal study in China

Fengchun Wu, Yuanyuan Huang, Yanling Zhou, Hehua Li, Bin Sun, Xiaomei Zhong, Xinni Luo, Yingjun Zheng, Hongbo He and Yuping Ning*The Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University/Guangzhou Huiai Hospital, Guangzhou, PR China

- *Corresponding Author:

- Yuping Ning

The Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University

Guangzhou Huiai Hospital, PR China

Accepted on February 6, 2017

Abstract

Identifying predictors of relapse in Schizophrenia (SZ) has been a hot issue since relapse is associated with worse clinical outcome. In this study, relapse rates of SZ patients after hospital discharge and their possible factors were investigated annually over 3 years to differentiate short-term and long-term predictors for relapse in SZ in China. According to the sequence of discharge date, 420 SZ patients were recruited. The severity of disease, compliance with medication use, social functions, and relapse rate were assessed at the time points of 1-, 2- and 3-year after hospital discharge. After each assessment, only the not-relapsed participants remained in the study for the next assessment. The factors influencing relapse in SZ were analysed by a logistic regression. Our results indicated that the relapse rate at 1-, 2- and 3-year after hospital discharge was 33.0%, 29.8%, and 16.4%, respectively. Compliance with medication use, communication skills, and work/study functioning were associated with relapse in SZ, with differential long-term and short-term effects. Especially, the compliance with medication use in the relapsed participants were significantly worse than that in the not-relapsed participants in three assessments over 3 years (P<0.001). Logistic regression analyses also revealed that SZ patients with worse compliance with medication use, communication skills, and work/study functioning showed higher risk of relapse. Importantly, worse compliance with medication use was associated with a 6.369-, 13.889-, and 8.850- fold increase in relapse at 1-, 2- and 3-year after hospital discharge, respectively (P<0.001). To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to investigate factors influencing relapse in SZ in China. Our results demonstrated that good compliance with medication use, communication skills, and work/study functioning may reduce the risk of relapse in SZ. The findings of this study suggested that good compliance with medication use is critical to prevention of SZ relapse.

Keywords

Schizophrenia, Relapse rate, Compliance with medication use, Social functions, Influencing factors.

Introduction

Schizophrenia (SZ) is a chronic mental disorder characterized with high rates of relapse and disability. The relapse of SZ is the characteristics of disease aggravation, leading to overall hypofunction, decreasing the working or learning ability [1] and increasing social and economic burden [2]. Over 50% of SZ patients present with repeated episode [3,4]. For patients with the first episode, the 1-year relapse rate is 28% on average, 43% for 1 to 1.5 years and 54% for 3 years [5]. Approximately 20% to 56% of patients have relatively poor compliance [6]. High relapse rate of SZ is a challenge for physicians. Poor compliance is the highest risk factor of SZ relapse [7]. Most previous studies are cross-sectional studies and only investigate severity of disease, compliance, and relapse rate at 1 year after hospital discharge; these studies show a large difference in relapse rates of SZ [5,7,8]. To identify the relationship between the relapse rate of SZ patients and influencing factors, a longitudinal study is necessary and of grate interest.

In this study, the severity of disease, compliance with medication use, social functions, and relapse rate were assessed at the time points of 1-, 2- and 3-year after hospital discharge. The relationships between relapse rates and influencing factors were analysed by logistic regression analyses. The findings of this study may provide evidences whether effective prevention is helpful to reduce the risk of relapse in SZ.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

According to the sequence of hospital discharge date, 420 patients diagnosed with SZ admitted to the Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University between September 2011 and August 2012 were recruited in this study. Written informed consents were signed by all patients or their relatives. The study procedures were in accordance with the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University.

Inclusion criteria

1) In accordance with the diagnostic criteria of SZ in ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision); 2) patients obtained “recovery” upon hospital discharge; 3) aged 18-65 years; 4) informed consents were signed by patients or their relatives.

Exclusion criteria

1) Patients with residual core symptoms upon hospital discharge; 2) those with unknown clinical efficacy upon hospital discharge; 3) those rejected to participate in this study; 4) those failed to attend follow-up by telephone.

Criteria of loss to follow-up

1) No telephone answering ≥ 3 times on different days; 2) those rejected to participate in this study after 3 times of explanation and persuasion at different time points; 3) wrong contact information.

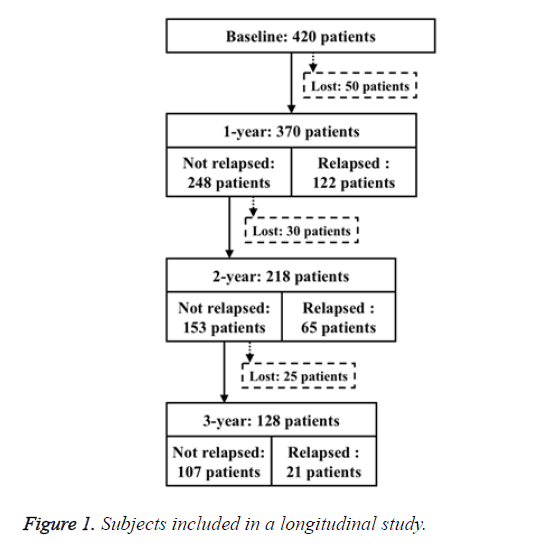

Finally, we included 370, 218, 128 SZ patients in the 1-, 2-, and 3-year assessment, respectively (Figure 1).

Methods

According to the clinical treatment, the questionnaire survey was self-invented and divided into the medical record and telephone investigations. The severity of disease, compliance with medication use, and social functions were obtained at the time points of 1-, 2- and 3-year after hospital discharge. After each assessment, only the not-relapsed participants remained in the study for the next assessment. According to the methods by Weiden et al. [9], compliance with medication use was classified into complete compliance and non-compliance (partial or non-compliance).

Questionnaire survey

1) Demographic data (e.g., gender, age, marriage status, residence place, educational background) and medical history of mental disorders (e.g., course of diseases, age of onset, frequency of hospitalization, days of hospital stay, family history) were obtained from medical record investigations; 2) telephone investigations included questions, such as frequency of re-examinations, current medication use, adverse drug reaction, compliance with medication use, possible reasons of non-compliance, attitudes of family members to medication use, relapse and possible factors, self-care ability of daily living, communication skills, work/study functioning, drinking, smoking.

Assessment of compliance with medication use

1) Complete compliance: Patients taking the medication strictly according to the doctor's advice or the time of non-compliance with the medication intake according to the doctor's advice<1 week; 2) partial compliance: in the recent 1 year, the time of non-compliance with the medication intake according to the doctor's advice ranging from l week to 6 month; the time of medication termination<1 week; 3) noncompliance: those opposed to medication or terminated the medication voluntarily ≥ 1 week, or the time of non-compliance with the medication intake according to the doctor's advice ≥ 6 months.

Diagnostic criteria for SZ relapse

Referring to the diagnostic criteria for SZ relapse [10], one of the following conditions should be met: 1) those requiring increasing dose or type of antipsychotics due to the fluctuation of patient's conditions; 2) those requiring higher frequency of out-patient or hospitalization due to unstable patient's conditions; 3) those requiring strengthened nursing care to avert the incidence of accident or danger due to the fluctuation of patient's conditions.

Investigators

All investigation procedures were accomplished by professional clinicians receiving training courses from the Department of Neurology. Both medical record and telephone investigations were completed by one single physician.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed by SPSS 18.0. Group comparisons between the relapsed and not-relapsed participants were analysed by using independent sample t-test, non-parametric rank-sum test, and chi-square test. The relationships between relapse rates and influencing factors were analysed by logistic regression analyses. A P-value of less than 0.05 (two-side) was considered as statistical significance.

Results

Baseline data

The demographic data and mental illness history of all subjects at baseline were shown in Table 1. Briefly, a total of 420 SZ patients were eligible for this study including 202 males (48.1%) and 218 females (51.9%), aged (36.6 ± 11.9) years on average; the age of onset was (26.5 ± 9.6) years; the mean length of hospital stay was (59.4 ± 1.9); the course of diseases was 7 years on average (3 to 15 years).

| Not-relapsed N=248 | Relapsed N=122 | t/χ2/z | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data and mental illness history | ||||

| Gender (male) | 117 (47.2%) | 61 (50.0%) | 0.261 | 0.658 |

| Age (years) | 35.5 ± 11.7 | 38.1 ± 12.7 | -1.936 | 0.054 |

| Marriage status (married) | 115 (46.4%) | 65 (53.3%) | 1.562 | 0.225 |

| Residence place (city) | 146 (58.9%) | 63 (51.6%) | 1.74 | 0.187 |

| Educational background (technical college above) | 60 (24.2%) | 15 (12.3%) | 8.931 | 0.2 |

| Course of diseases (year) | 7 (3, 13) | 8.5 (2.8, 20) | -1.757 | 0.079 |

| Age of onset (year) | 26.5 ± 10.0 | 26.34 ± 9.0 | 0.154 | 0.878 |

| Frequency of hospitalization | ||||

| (≥ 4 times) | 52 (21.0%) | 46 (37.7%) | 11.765 | 0.001** |

| Days of hospital stay | 60.5 ± 1.92 | 57.24 ± 1.9 | 0.755 | 0.451 |

| Family history (Yes) | 70 (28.2%) | 27 (22.1%) | 1.57 | 0.258 |

| At 1 year after hospital discharge | ||||

| Compliance with medication use (good) | 197 (79.4%) | 62 (50.8%) | 31.886 | <0.001** |

| Communication skills (good) | 152 (61.3%) | 39 (31.9%) | 28.154 | <0.001** |

| Work/ study functioning (Yes) | 180 (72.6%) | 77 (63.1%) | 3.454 | 0.063 |

| Note: *denotes P<0.05, **denotes P<0.01. | ||||

Table 1. Comparison of clinical parameters between the relapsed and not-relapsed patients at 1 year after hospital discharge.

Comparison of SZ relapse and influencing factors

The relapse rate at 1-, 2- and 3-year after hospital discharge was 33.0%, 29.8%, and 16.4%, respectively. The overall rate relapse of 3 years was 58.0%.

In the assessment of 1-year after hospital discharge, 50 patients were lost to follow-up and 370 completed the follow-up. Compared with the relapsed participants, the non-relapsed participants showed better compliance with medication use (χ2=31.886, P<0.001) and better communication skills (χ2=28.154, P<0.001), as shown in Table 1.

In the assessment of 2-year after hospital discharge, 30 patients were lost to follow-up and 218 completed the follow-up. Compared with the relapsed participants, the non-relapsed participants showed better compliance with medication use (χ2=62.668, P<0.001), better communication skills (χ2=22.388, P<0.001), and better work/ study functioning (χ2=10.472, P=0.001). However, no significance was found in these factors between two groups in the assessment of 1-year after hospital discharge, as shown in Table 2.

| Not-relapsed N=153 | Relapsed N=65 | t/χ2/z | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data and mental illness history | ||||

| Gender (male) | 73 (47.7%) | 29 (44.6%) | 0.176 | 0.675 |

| Age (years) | 36 ± 11.1 | 34.8 ± 11.8 | 0.713 | 0.477 |

| Marriage status (married) | 71 (46.1%) | 30 (46.2%) | 0.001 | 0.973 |

| Residence place (city) | 93 (60.8%) | 36 (55.4%) | 0.551 | 0.485 |

| Educational background (technical college above) | 38 (24.8%) | 13 (20.0%) | 3.078 | 0.745 |

| Course of diseases (year) | 8 (3, 13) | 6 (3, 14.5) | -0.267 | 0.782 |

| Age of onset (year) | 26.6 ± 9.8 | 25.5 ± 10.3 | 0.724 | 0.47 |

| Frequency of hospitalization | ||||

| (≥4 times) | 36 (23.5%) | 13 (20.0%) | -0.479 | 0.632 |

| Days of hospital stay | 59.5 ± 1.8 | 65.4 ± 1.9 | -1.019 | 0.309 |

| Family history (Yes) | 40 (26.1%) | 20 (30.8%) | 0.489 | 0.484 |

| At 2 year after hospital discharge | ||||

| Compliance with medication use (good) | 197 (79.4%) | 62 (50.8%) | 31.886 | <0.001** |

| Communication skills (good) | 152 (61.3%) | 39 (31.9%) | 28.154 | <0.001** |

| Work/ study functioning (Yes) | 180 (72.6%) | 77 (63.1%) | 3.454 | 0.063 |

| Note: *denotes P<0.05, **denotes P<0.01. | ||||

Table 2. Comparison of clinical parameters between the relapsed and not-relapsed patients at 2 year after hospital discharge.

In the assessment of 3-year after hospital discharge, 25 patients were lost to follow-up and 128 completed the follow-up. Compared with the relapsed participants, the non-relapsed participants showed better compliance with medication use (χ2=20.713, P<0.001), better communication skills (χ2=7.149, P=0.008), and better work/ study functioning (χ2=12.339, P<0.001). However, no significance was found in these factors between two groups in the assessment of 2-year after hospital discharge, as shown in Table 3.

| Not-relapsed N=107 | Relapsed N=21 | t/χ2/z | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data and mental illness history | ||||

| Gender (male) | 51 (47.7%) | 10 (47.6%) | 0 | 0.997 |

| Age (years) | 36.9 ± 10.9 | 31.9 ± 11.2 | 1.893 | 0.061 |

| Marriage status (married) | 51 (47.7%) | 9 (42.90%) | 0.163 | 0.687 |

| Residence place (city) | 61 (57.0%) | 13 (61.9%) | 0.172 | 0.678 |

| Educational background (technical college above) | 30 (28%) | 2 (9.6%) | 11.831 | 0.014* |

| Course of diseases (year) | 8 (4, 14) | 8 (3, 12.5) | -0.444 | 0.657 |

| Age of onset (year) | 26.6 ± 9.6 | 23.7 ± 9.0 | 1.314 | 0.191 |

| Frequency of hospitalization | ||||

| (≥ 4 times) | 27 (25.2%) | 7 (33.3%) | -0.623 | 0.533 |

| Days of hospital stay | 59.8 ± 1.9 | 53.0 ± 2.0 | 0.717 | 0.474 |

| Family history (Yes) | 32 (29.9%) | 3 (14.3) | 2.156 | 0.142 |

| At 2 year after hospital discharge | ||||

| Compliance with medication use (good) | 89 (83.2%) | 18 (85.7%) | 0.082 | 0.774 |

| Communication skills (good) | 91 (85%) | 16 (76.2%) | 1.004 | 0.316 |

| Work/study functioning (Yes) | 86 (80.4%) | 15 (71.4%) | 0.884 | 0.358 |

| At 3 year after hospital discharge | ||||

| Compliance with medication use (good) | 87 (81.3%) | 14 (66.7%) | 20.713 | <0.001** |

| Communication skills (good) | 89 (83.2%) | 12 (57.1%) | 7.149 | 0.008** |

| Work/ study functioning (Yes) | 74 (69.2%) | 6 (28.6%) | 12.339 | <0.001** |

Table 3. Comparison of clinical parameters between the relapsed and not-relapsed patients at 3 year after hospital discharge.

Logistic regression analyses

In the assessment of 1-year after hospital discharge, the relapse of SZ was used as a dependent variable; the frequency of hospitalization, compliance with medication use, communication skills, and work/study functioning were regarded as the independent variables for the logistic regression analysis. Participants with better compliance with medication use (OR=6.369, P<0.001) or better communication skills (OR=2.653, P<0.001) had a lower risk of SZ relapse, as shown in Table 4.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | B | S.E. | Wald | P | Exp (B) | 95% CI for EXP (B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| 1-year schizophrenia relapse | Poor compliance (vs. good compliance)a | 1.851 | 0.307 | 36.334 | <0.001 | 6.369 | 3.484 | 11.628 |

| Poor communication skills (vs. good communication skills)a | 0.976 | 0.252 | 14.961 | <0.001 | 2.653 | 1.618 | 4.348 | |

| Note: aRepresents follow-up status at 1 year after hospital discharge. | ||||||||

Table 4. Logistic regression analysis of factors influencing relapse in schizophrenia at 1 year after hospital discharge.

In the assessment of 2-year after hospital discharge, the relapse of SZ at 2-year was used as a dependent variable; the frequency of hospitalization at 1-year assessment, compliance with medication use, communication skills, and work/study functioning at both 1-year and 2-year assessments were regarded as the independent variables for the logistic regression analysis. Participants with better compliance with medication use (OR=13.889, P<0.001), or better communication skills (OR=3.413, P=0.002), or work/study functioning (OR=2.611, P=0.019) had a lower risk of SZ relapse, as shown in Table 5.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | B | S.E. | Wald | P | Exp (B) | 95% CI for EXP (B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| 2-year schizophrenia relapse | Poor compliance (vs. good compliance)a | 2.633 | 0.386 | 46.582 | <0.001 | 13.889 | 6.536 | 29.412 |

| Poor communication skills (vs. good communication skills)a | 1.228 | 0.395 | 9.678 | 0.002 | 3.413 | 1.575 | 7.407 | |

| No work/study (vs. work/ study)b | 0.96 | 0.409 | 5.501 | 0.019 | 2.611 | 1.171 | 5.814 | |

| Note: aRepresents follow-up status at 1 year after hospital discharge; bRepresents follow-up status at 2 years after hospital discharge. | ||||||||

Table 5. Logistic regression analysis of factors influencing relapse in schizophrenia at 2 year after hospital discharge.

In the assessment of 3-year after hospital discharge, the relapse of SZ at 3-year was used as a dependent variable; the frequency of hospitalization at 1-year, compliance with medication use, communication skills, and work/study functioning at both 2-year and 3-year assessments were regarded as the independent variables for the logistic regression analysis. Participants with better compliance with medication use (OR=8.850, P<0.001) or work/study functioning (OR=5.714, P=0.002) had a lower risk of SZ relapse, as shown in Table 6.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | B | S.E. | Wald | P | Exp(B) | 95% CI for EXP(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| 3-year schizophrenia relapse | Poor compliance (vs. good compliance)a | 2.179 | 0.561 | 15.081 | <0.001 | 8.85 | 2.941 | 26.315 |

| Poor communication skills (vs. good communication skills)a | 1.742 | 0.575 | 9.172 | 0.002 | 5.714 | 1.848 | 17.513 | |

| Note: aRepresents follow-up status at 3 year after hospital discharge. | ||||||||

Table 6. Logistic regression analysis of factors influencing relapse in schizophrenia at 3 year after hospital discharge.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to investigate factors influencing relapse in SZ in China. Our results indicated that: 1) the risk of SZ relapse was the highest at 1-year after hospital discharge and the relapse rate declined year by year; 2) compliance with medication use, communication skills, and work/study functioning were associated with relapse in SZ, with differential long-term and short-term effects; 3) SZ patients with worse compliance with medication use, communication skills, and work/study functioning showed higher risk of relapse.

A number of previous studies have indicated risk factors of SZ relapse, such as worse compliance with medication use, stressful event, substance abuse and insufficient family and social support [5,11-15]. In this longitudinal study over 3 years, we indicated that the rate of SZ relapse was associated with compliance with medication use, communication skills, and work/study functioning. Importantly, the compliance with medication use in the relapsed participants was significantly worse than that in the not-relapsed participants in three assessments over 3 years. Moreover, worse compliance with medication use was associated with a 6.369-, 13.889-, and 8.850- fold increase in relapse at 1-, 2- and 3-year after hospital discharge, respectively. These findings were consistent with a previous study, in which the percentage of patients with non-compliance with medication use was ranged from 20% to 60.26% [6]. Therefore, we speculated that poor compliance was a major factor influencing relapse in SZ [7,8].

Interestingly, our results showed that the relapse rate was associated with the compliance with medication use in the year, but not with that in the previous year. This finding suggested that the compliance after discharge could predict the short-term effect rather than the long-term effect. Therefore, persistent monitoring is necessary for patients with good compliance with medicine use. Most SZ patients neglect the importance of maintenance of therapy and ignore that compliance of medication use may decline over time [16]. The decline of compliance constantly leads to the relapse in SZ [17]. The relapse in SZ should be highly monitored when the compliance becomes worse. Therefore, the importance of medication use should be delivered to patients during hospitalization and after hospital discharge. After hospital discharge, persistent treatment should be implemented to strengthen the compliance with medication use, which can fundamentally decrease the long-term relapse rate.

In this study, communication skills of relapsed patients significantly differed in three follow-up assessments; work/ study functioning also significantly differed in two follow-up assessments. Compared with not-relapsed patients, social functions were severely damaged for relapsed patients. These results were consistent with previous findings regarding the damages of work and communication in SZ patients [18,19]. Negative symptoms were more likely to impact the communication and social skills of the patients [20]. Menendez et al. [21] indicate that psychopathology affected subjective social functions, whereas the severity of disease and negative symptoms influenced social functions. Improvement of social functions has become an ultimate objective of clinical treatment [22].

Throughout the 3-year follow-up assessments, the factors influencing relapse in SZ significantly varied, suggesting that short-term and long-term influencing factors might differ. During 2- and 3-year after hospital discharge, work/study functioning was an influencing factor of SZ relapse, whereas no statistical significance was observed during the 1st year after discharge, suggesting that work/study functioning mainly affects the long-term relapse rate of schizophrenia. Moreover, patients with higher frequency of hospitalization presented with a higher relapse rate at 1 year after discharge rather than during 2- and 3-year after discharge, suggesting that the frequency of hospitalization is more likely to affect short-term relapse rate. Previous investigations have demonstrated that the frequency of hospitalization is increased and the interval of hospitalization is shortened [11]. Short-term relapse even readmission is probably subject to the influence of the disease itself, especially for lack of self-recognition ability.

There were several limitations in this study. First, the follow-up survey was conducted via telephone and some of the relatives failed to completely answer the questions in details. Second, the patient’s condition was not evaluated by an objective evaluation scale, which reduced the accuracy to certain extent. Third, the confounding factors of influencing factors of SZ relapse were not excluded. In future studies, we'll explore a more detailed questionnaire, include the evaluation scale and conduct laboratory examination to further identify the influencing factors of SZ relapse and provide evidence for clinical diagnosis and treatment of SZ for clinicians.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that good compliance with medication use, communication skills, and work/study functioning may reduce the risk of relapse in SZ. The relapse rate was not affected by the compliance or social functions in the previous year. Persistent treatment after hospital discharge can effectively reduce the rate of SZ relapse. The short-term and long-term influencing factors of SZ relapse were inconsistent. Worse compliance and declined work/study functioning were risk factors of long-term SZ relapse. Medical staff, relative, and social supports contribute to recovery of SZ and prevention of SZ relapse.

Acknowledgement

Our study was supported by Science and Technology Program of Guangdong (Project Number: 2016A020216004) and Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (Project Number: 2014Y2-00105, 2017010160496; Application Number: 201605122303495).

References

- Kane JM. Treatment strategies to prevent relapse and encourage remission. J Clin Psychiatry 2007; 68: 27-30.

- Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, Salkever D, Slade EP. The cost of relapse and the predictors of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 2010; 10: 2.

- Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162: 441-449.

- McIntyre RS, Fallu A, Konarski JZ. Measurable outcomes in psychiatric disorders: remission as a marker of wellness. Clin Ther 2006; 28: 1882-1891.

- Alvarez-Jimenez M, Priede A, Hetrick SE, Bendall S, Killackey E. Risk factors for relapse following treatment for first episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Schizophr Res 2012; 139: 116-128.

- Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, Leckband SG, Jeste DV. Prevalence of and risk factors for medication non-adherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63: 892-909.

- Kao YC, Liu YP. Compliance and schizophrenia: the predictive potential of insight into illness, symptoms, and side effects. Compr Psychiatry 2010; 51: 557-565.

- Mi WF, Zou LY, Li ZM. Compliance with antipsychotic treatment and relapse in schizophrenia. Chin J Psychiatry 2012; 45: 25-28.

- Weiden P, Rapkin B, Mott T, Zygmunt A, Goldman D. Rating of medication influences (ROMI) scale in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1994; 20: 297-310.

- Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, Morozova M, Eerdekens M. Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res 2010; 116: 107-117.

- Rabinowitz J, Mark M, Popper M, Slyuzberg M, Munitz H. Predicting revolving-door patients in a 9-year national sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1995; 30: 65-72.

- Chabungbam G, Avasthi A, Sharan P. Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with relapse in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2007; 61: 587-593.

- Leucht S, Tardy M, Komossa K, Heres S, Kissling W. Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012; 379: 2063-2071.

- Horan WP, Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, Hwang SS, Mintz J. Stressful life events in recent-onset schizophrenia: reduced frequencies and altered subjective appraisals. Schizophr Res 2005; 75: 363-374.

- Verdoux H. Factors associated with risk of relapse and outcome of persons with schizophrenia. Rev Prat 2013; 63: 343-348.

- Sapra M, Vahia IV, Reyes PN, Ramirez P, Cohen CI. Subjective reasons for adherence to psychotropic medication and associated factors among older adults with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2008; 106: 348-355.

- Marder SR, Glynn SM, Wirshing WC, Wirshing DA, Ross D. Maintenance treatment of schizophrenia with risperidone or haloperidol: 2-year outcomes. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160: 1405-1412.

- Bae SM, Lee SH, Park YM, Hyun MH, Yoon H. Predictive factors of social functioning in patients with schizophrenia: exploration for the best combination of variables using data mining. Psychiatry Investig 2010; 7: 93-101.

- Harvey PD. Disability in schizophrenia: contributing factors and validated assessments. J Clin Psychiatry 2014; 75: 15-20.

- Harvey PD, Heaton RK, Carpenter WT, Green MF, Gold JM, Schoenbaum M. Functional impairment in people with schizophrenia: focus on employability and eligibility for disability compensation. Schizophr Res 2012; 140: 1-8.

- Menendez-Miranda I, Garcia-Portilla MP, Garcia-Alvarez L, Arrojo M, Sanchez P. Predictive factors of functional capacity and real-world functioning in patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry 2015; 30: 622-627.

- Burns T, Patrick D. Social functioning as an outcome measure in schizophrenia studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007; 116: 403-418.