Research Article - Journal of Public Health Policy and Planning (2021) Volume 5, Issue 12

Exploring sexual and reproductive health knowledge among adolescents in the Ghanaian society a situational study of Komenda community in the Komenda Edina Eguafo Abrem (KEEA) municipality in the central region of Ghana.

Charles Owusu-Aduomi Botchweya1*, Francis Acquahb1, Richmond Opokuc2, Agartha Afful Boatengd1, Lawrencia Aggrey-Bluweye11Department of Health Administration and Education, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana

2Department of Public Health Education, University of Skills Training and Entrepreneurial Development, Mampong, Ghana

- *Corresponding Author:

- Charles Owusu-Aduomi Botchweya

Department of Health Administration and Education

University of Education, Winneba, Ghana

E-mail: chaboat08@yahoo.com/coabotchwey@uew.edu.gh

Accepted date: December 27, 2021

Citation: Botchweya CO, Acquahb F, Opokuc R, Boatengd AA, Aggrey-Bluweye L. Exploring sexual and reproductive health knowledge among adolescents in the Ghanaian society a situational study of Komenda community in the Komenda Edina Eguafo Abrem (KEEA) municipality in the central region of Ghana. 2021; 5(12):116-129

Abstract

Introduction: Sexual and Reproductive Health is very critical in all aspects of all Homo sapiens including their physical, mental, social, economic and emotional well-being. Of much important and concern is that of the adolescents who are globally said to be the most vulnerable group to this aspect of health. Aim: This study was designed to explore the sexual and reproductive health knowledge of adolescents in the Central Region of Ghana with Komenda as the case study. Methodology: A mixed method with a case study design was adopted through quantitative survey and focus group discussions among 95 adolescents in the Komenda community. Results and discussion: The findings indicated that the knowledge of adolescents in Komenda community on sexual and reproductive health was generally poor. Religion and culture were found to be the major cause of poor sexual and reproductive health knowledge among these adolescents. Similarly, schools were found to be the most prominent source and most preferred place that adolescents in the study will want to learn about sexual and reproductive health from. As to who they will prefer to discuss their sexual and reproductive health issues with, it was found to be relative thus depends on the type of issue at hand and the prevailing conditions surrounding it. The study equally identified that poor sexual and reproductive health was found to be very intense and inimical to the long term well-being of the adolescents and the family. Recommendation: The study recommends that sexual and reproductive health programmes or projects by government and other stakeholders be designed to overcome both cultural and religious barriers. Additionally, future researches to investigate other areas of sexual and reproductive health and their relationship with socio-demographic characteristics of the adolescents should be embarked on. Conclusion: It is imperative to mention that for a successful implementation of sexual and reproductive health policies to yield fruition, religion, culture, knowledge and availability of sexual and reproductive health services should be seen as the building blocks.Keywords

Homo sapiens, Well-being, Globally, Socio-economic, Vulnerable, Sexual and reproductive health knowledge

Introduction

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has defined adolescence as the age range of 10 to 19 years. It is the period between childhood and adulthood, marked by physical growth, attainment of a mature structure, learning of physical characteristics, mental maturation and the development of secondary-sex characteristics. There are 1.2 billion adolescents representing 16% of the world population [1].

While adolescents generally enjoy good health compared with other age groups, adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) constitutes a major component of global burden of ill-health and therefore needs special attention. Adolescents face particular health risks, which may be detrimental not only for their immediate future but for the rest of their lives. High prevalence of HIV, teenage pregnancy and unsafe abortions are challenges faced by many countries especially in Sub-Saharan Africa [2].

Research has shown that many of the health problems that arise are due to a lack of general basic understanding on “reproductive biology and prevention methods” [2]. The health of adolescents and particularly their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) are of particular concern for a number of reasons: adolescents account for 23% of the overall burden of disease (disabilityadjusted life years) because of pregnancy and childbirth [3]. WHO estimated 16 million births annually occur to young women aged 15 to 19 years, representing 11% of all births. Almost all (95%) of adolescent births take place in developing countries. 18% and 50% of births annually in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa respectively occur during adolescence. Approximately 2.5 million births occur to girls aged 12 to 15 years in low-resourced countries each year of which around a million births occur to girls younger than 16 years in Africa. Early childbearing is linked with higher maternal mortality and morbidity rates and increased risk of induced mostly illegal and unsafe abortions. Maternal deaths constitute the leading cause of death among adolescent females [4]. Of the estimated 22 million unsafe abortions that occur every year, 15% occur among young women aged 15 to19 years. An estimated one million young people aged 15 to 24 years are infected with HIV every year representing 41% of all new infections among those aged 15 years and older. Most of these conditions, death and illness can be avoided. Gender-based violence is also too common a reality for many adolescents, especially girls [3].

What is even alarming is that whilst mortality rate is consistently reducing from all regions; it is still escalating and highest in Africa, increasing the global mortality in adolescents [5].

According to the 2014 Ghana Demographic and Health Survey [6], Ghana is characterised by a young population with 14% and 13% in the 5-9 and 10-14 age groups, respectively. Adolescents aged 10-19 and young adults aged 20-24 together constitute 29.3% of Ghana's population (21.9% and 7.4%, respectively).Adolescent just like in other developing countries face challenges related to sexual and reproductive health, for example STIs including HIV, as well as malnutrition, mental health, substance use, non-communicable diseases, intentional and unintentional injuries, various forms of violence, inequities and risks and vulnerabilities linked with child marriage, child labour, trafficking as well as disabilities. A number of initiatives have been undertaken in Ghana since 1980 culminating the launching of the National Adolescent Health and Development (ADHD) programme in 2001. A seven-year (2009-2015) National ADHD Strategic Plan was developed in 2009 which sought to provide a multi-sectorial support to every young person living in Ghana with education and information that will lead to the adoption of a healthy lifestyle physically, sexually, psychologically and socially.

Although many gains have been made over the past decades as a result of such initiatives, for example, the rate of new HIV infections among 15-19 year adolescents has decreased by 40%. The proportion of females aged below 20 years who deliver with the assistance of a skilled provider increased to 72 percent, however birth rate among adolescents aged 15-19 remains high. Central region consistently ranked as the second region with highest prevalence rate in teenage pregnancy in Ghana for example, recorded more than 13,000 teenage pregnancies in 2016 [7]. Again, 2020 data from GHS depict that teenage pregnancy is still a big challenge in Ghana. According to GHS, Ghana recorded 1,098,888 teen pregnancies with the lowest girls to be put in the family way being ten years old. Per the data girls between the ages of 10 and 14 accounts for 2,865 in pregnancies recorded in 2020 whilst another 107,023 girls between the ages of 15 to 19 were impregnated within same year. This infer that in every one hour, there were 301 teen pregnancies in 2020. Ashanti Region was the region with the highest number of teen pregnancies (17,802), followed by Eastern Region (10,865).

Central Region the focus of this study was the third region with the highest number of teen pregnancies (10,301). Analysing the data from case to population ratio makes the region the highest with teen pregnancy in Ghana. KEEA municipality for which Komenda is one of the circuits is one of the hot spot areas in the region where most adolescent faces these challenges (GHS annual teen pregnancy report, 2020).

All these phenomena show that there is a gap that needs to be filled upon all governmental and Non-Governmental Organisations’ (NGOs) efforts to significantly reduce such unhealthy sexual and reproductive incidents in the region and the country at large.

It is against this background that this study seeks to explore the sexual and reproductive health knowledge of adolescents in central region of Ghana using Komenda in the Komeneda Edina Eguafo Abrem municipality in the central region of Ghana as a case study.

Exploring the knowledge that adolescents possess on sexual and reproductive health will enable stakeholders and policy makers plan for comprehensive strategies for helping them by addressing their knowledge gaps. This is because sexual and related risk behaviours among adolescents can be reduced through raise of awareness about STDs, abortion, early pregnancies and the related sociocultural factors (Leshabari et al., 2008).

Generally, this study aims at empirically assessing knowledge on sexual and reproductive health among adolescents in Komenda in the Central Region of Ghana.

Specifically, the study sought to achieve the following:

(i) Explore the causes of poor knowledge on sexual and reproductive health among adolescent in Komenda community in the Central Region.

(ii) Propose methods of enhancing the knowledge in sexual and reproductive health of the youth of Komenda community in the Central Region of Ghana.

(iii) Determine the effects of poor knowledge on sexual and reproductive health on the socioeconomic development of youth of Komenda community in the Central Region.

Materials and Methods

The study used the following materials: the encyclopedia, quetext, and grammarly. The encyclopedia was used to check the meanings of new vocabulary items which were strange to the researchers. The quetext was used to identify plagiarized contents whilst the grammarly was useful in checking spelling mistakes and grammatical errors.

The study employed the mixed method with a case study design. A case study is a research approach that is used to generate an in-depth, multi-faceted understanding of a complex issue in its real-life context. It is used to explain, describe or explore events or phenomena in the everyday contexts in which they occur (Crowe et al., and Yin). Specifically, the study employed the observational case study where data were collected by participant observation which was then enhanced by a focus group discussion. Mixed method research is the type of research in which a researcher or team of researchers combines elements of qualitative and quantitative research approaches for the broad purposes of breadth and depth understanding and confirmation [8]. Combination of these techniques is said to enable the researcher to minimise subjectivity of judgment [9], but also give room for personal experiences by the participants. Thus such integration permits a more complete and synergistic utilisation of data than do separate quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis. The qualitative data obtained for example assisted in obtaining a more realistic data of the investigation that could otherwise would have not been experienced relying on the numerical data and statistical analysis using the quantitative research design alone.

The study population for this research constitutes adolescents in Komenda community in the Central Region of Ghana.

The study took into consideration both inclusion and exclusion criteria in the selection of the study population.

The sample size used for this study was drawn from a pool of adolescents in the Komenda community. As a part a qualitative study, the sample size was determined using the principle of saturations. Guest et al. [10] refer to it as having become ‘the gold standard by which purposive sample sizes are determined in health science research. The principle of saturation was used to reduce repetitiveness of respondents’ responses and the collection of large responses that does not add up to what had been collected [11]. A total of 95 respondents were therefore deployed for the study. This sample size to the greater extent was large enough to mimic the true characteristics of the population being studied.

The study used both simple random sampling and purposeful sampling techniques to equitably select adolescents with varied age range, academic and socioeconomic background from all seventeen electoral areas in the Komenda community to make a total number of ninety-five (95) adolescents. The simple random sampling was used to handle the quantitative aspect of the research whilst the purposeful sampling technique was also used to deal with the qualitative aspect. This collectively enabled the recruitment of participants who provided in-depth and detailed information about the study under investigation taking research objectives and questions into consideration.

Therefore, taking into account of the very space of this study, questionnaire and focus group discussion guide (in-depth interview guide) were used as instrument to assess knowledge and the experiences of adolescents on sexual and reproduction health.

Data were collected using an in-depth interview guide for focused group discussion, questionnaires, field notes and tape recorder. Sixty questionnaires were purposefully and randomly distributed among the adolescents who met the inclusive criteria in all the sixteen electoral areas of Komenda community. Again, seven focus groups made up of five participants of same sex each was also held in different electoral areas in Komenda community with the help of focus group guide. In all 35 adolescents comprising of 20 females and 15 males were deployed for the focus group discussions. At the end of each focus group discussion, study participants were given an opportunity to ask questions related to the discussion. Each group discussion lasted for an average of one hour-thirty minutes. Discussions were held in both “Fante” (local language of the people) and English. A semi-circular sitting arrangement was planned to ensure there was a good communication between the study participants and the researchers.

Very conscious of the ethical issues and guidelines for research on reproductive health involving minors [3], permission was sought from University of Education, Winneba where the researchers are affiliated to, leaders of Komenda community where the research was conducted and the KEEA municipal assembly. Consent from participants, their guardian, teachers or parents were also considered as well as adherence to confidentiality and anonymity of study participants within and after the said study period. In summary all ethical issues were strictly adhered to.

Data collected from the questionnaires were analysed using SPSS software; version 19 and Microsoft excel 2019. Descriptive data were presented as simple frequencies and percentages whilst data analysis from the focus group discussions commenced with transcribing, translating, reviewing and coding of interview excerpts. This enabled conceptualisation and categorisation of key themes emanating from the data.

Findings and Discussions

Findings

Demographic characteristics of respondents

Ninety five (95) respondents participated in the study. Sixty (60) of them were made to respond to the questionnaires whilst the remaining thirty five (35) were used for the focus group discussions. The mean age of the participants was 16.9 whilst the median age was calculated to be 17 with 18 being the modal age. The standard deviation for the distribution of the ages was found to be 1.61. The demographic characteristics of the participants have been presented in Table 1.

| Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 10.-15 | 23 | 24.21 |

| 16-19 | 72 | 75.79 |

| Total | 95 | 100 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 43 | 45.26 |

| Female | 52 | 54.74 |

| Total | 95 | 100 |

| Religion | ||

| Christianity | 70 | 73.68 |

| Islamic | 25 | 26.32 |

| Total | 95 | 100 |

| Education level | ||

| Tertiary | 3 | 3.16 |

| Senior High School | 36 | 37.89 |

| Junior High School | 40 | 42.11 |

| Primary | 16 | 16.84 |

| Total | 95 | 100 |

| Marital status | ||

| Co-habiting | 7 | 7.37 |

| Not married | 25 | 26.32 |

| In a relationship | 50 | 52.63 |

| Single | 13 | 13.68 |

| Total | 95 | 100 |

| What they do | ||

| Student | 65 | 68.42 |

| Trading | 14 | 14.74 |

| Others | 16 | 16.84 |

| Total | 95 | 100 |

| Who they stay with | ||

| Parents | 60 | 63.16 |

| Guardian | 26 | 27.37 |

| Others | 9 | 9.47 |

| Total | 95 | 100 |

| Number of child or children | ||

| Yes | 17 | 17.89 |

| No | 78 | 82.11 |

| Total | 95 | 100 |

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of both questionnaires and focus group.

Knowledge on sexual and reproductive health in general

As Table 2 and Table 3 depict, 60 out of the 95 study participants who responded to the items on the questionnaires’ knowledge on general SRH were explored. When asked to respond whether they were conversant with the term SRH, 52 respondents representing 86.7% of the respondents responded “YES” whilst the remaining 13.3% responded “NO”. To further test their assertions, those who responded “YES” were made to respond to a list of options that they thought were under the broad area of SRH. 50 respondents recognised “sex education” as being part of SRH and more than half of the respondents also chose “STIs prevention” and “pregnancy” as part of broad areas of SRH. More than third of the respondents also recognised “human right” and “abortion” as being part of the broad scope of SRH. However, only 18 of the respondents considered “contraceptives” to be inclusive of the broad areas of SRH.

| Responses | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 52 | 86.7 |

| No | 8 | 13.3 |

Table 2: Respondents responses recognition of SRH.

| Number of Respondents = 52 | ||

|---|---|---|

| SRH Areas | Frequency | Percentage ( area/52 times 100) % |

| Sex education | 50 | 96.15 |

| STI prevention | 31 | 59.62 |

| Contraceptives | 18 | 34.62 |

| Human Right | 20 | 38.46 |

| Pregnancy | 30 | 57.69 |

| Abortion | 21 | 40.38 |

Table 3: Responses of respondents to what SRH covers.

Meanwhile when engaged in focus group discussions to ascertain what the term SRH meant to others. It was found that their understanding on what SRH entailed was so skeptical. Some admitted that they have not heard about it before. Many of them understood it from the biological perspective of health as some of them put it in similar ways as:

“Sexual and reproduction in my opinion is about keeping your private parts clean.”

“It is about personal hygiene and keeping the body free from disease.”

“It is the health about your sexual and reproductive organ.”

Others also understood it as the activities that go on in the relationships between male and female as one male explained;

“It means male and female having sexual affairs.”

No one was able to comprehend and conceptualise SRH as a concept so comprehensive in it nature as defined by authorities such as WHO and ICPD.

Knowledge on contraceptives and pregnancy

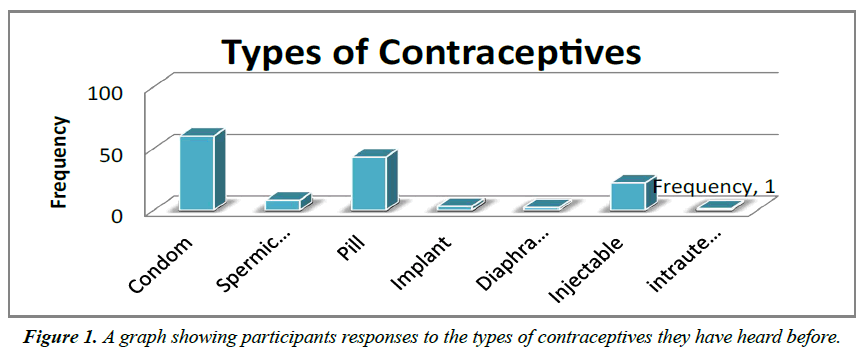

The study assessed the knowledge on contraceptive and pregnancy, for example, “what contraceptives are”, types of contraceptives they know or have heard”, “do contraceptives have side effect”, “can one use contraceptives and still get pregnant and STDs” via the questionnaire. A total of 54 out of the 60 (90%) respondents claimed to know what contraceptives were. When made to respond to as many as applicable to them what contraceptives were used for, 36 and 41 out of the 54 respondents who claimed to know what contraceptives were revealed that contraceptives were used to prevent disease and prevent pregnancy respectively. 22 of the 54 (40.7%) respondents unfortunately thought that contraceptives were also used for abortion. Then again, the 60 respondents were made to respond to which of these thus condom, implant, injectable, spermicide, diaphragm, sterilisation, pill, cervical cap and intrauterine device they had heard of, 100% of the 60 respondents selected condom, the second known contraceptive was pill representing 71% of the total respondents with diaphragm (3.3%) and intrauterine device (1.7%) being the least known contraceptives as shown in Figure 1. Again almost half of the respondents did not know that one could use contraceptives and still get STDs or pregnant. Approximately one third of the respondents also never knew that contraceptives had side effects. Table 4 shows the details of the responses to each item.

| Item | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Do you know contraceptives what contraceptives are? | ||

| Yes | 54 | 90 |

| No | 6 | 10 |

| What contraceptives are used for? | ||

| Use to prevent diseases | 36 | 66.7 |

| Use to prevent pregnancy | 41 | 75.9 |

| Use to do abortion | 22 | 40.7 |

| Which of these have you heard of? | ||

| Condom | 60 | 100 |

| Spermicide | 8 | 13.3 |

| Pill | 43 | 71.7 |

| Implant | 3 | 5 |

| Diaphragm | 2 | 3.3 |

| Injectable | 22 | 36.7 |

| intrauterine device | 1 | 1.7 |

| Can you use contraceptives and still get STDs? | ||

| Yes | 31 | 51.7 |

| No | 29 | 48.3 |

| If yes what contraceptives is best for preventing STDs? | ||

| Condom | 27 | 87.1 |

| Injectable | 4 | 12.9 |

| Can one use contraceptives and still get pregnant? | ||

| Yes | 34 | 56.7 |

| No | 26 | 43.3 |

| If Yes what contraceptives is best for preventing pregnancies? | ||

| Condom | 17 | 50 |

| Spermicide | 3 | 8.8 |

| Pill | 7 | 20.6 |

| Implant | 1 | 2.9 |

| Injectable | 6 | 17.6 |

| Do contraceptives have side effect? | ||

| Yes | 39 | 65 |

| No | 21 | 35 |

Table 4: Responses on knowledge on contraceptives and pregnancy.

When those who responded “YES” as to the fact that contraceptives had side were probed to state the effect of contraceptives, 4 of them stated the general effect of contraceptives as causing death, 9 of the respondents stated injectable (family planning) as causing bareness, overweight and delaying of pregnancy in the future. Similarly, 16 of the respondents also cited white, rashes, bursting and leaking as the side effects of using condom. The remaining of the respondents cited womb destruction, bleeding, infertility, abortion and changes in menstrual cycle as the side effects of pill.

Knowledge on STDS including HIV

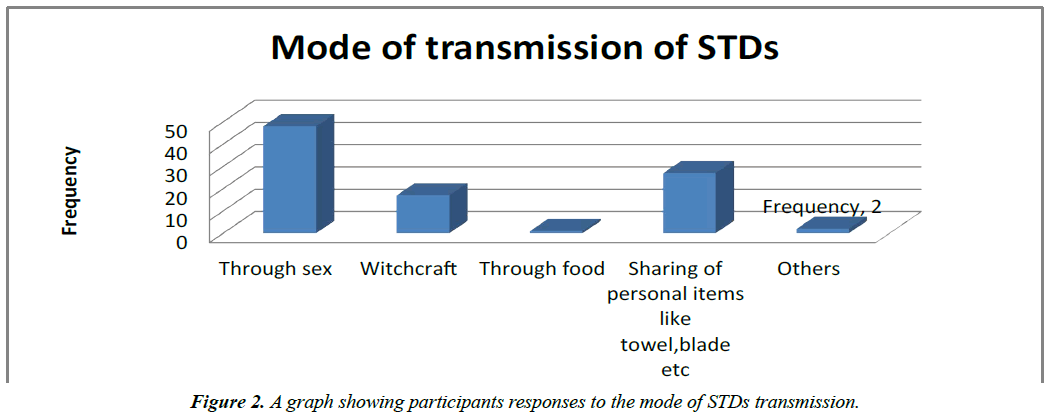

Knowledge on STDs including HIV was being assessed via survey and focus group discussion. The study showed as detailed in Table 5 that 50 out 60 of the respondents who responded to the questionnaire claimed to know what STDs were. Those who responded “YES” as usual knowledge on STDs were being probed further to know whether they knew its mode of transmission of STDs. 48 out of the 50 respondents (96%) knew that it could be transmitted through “sex”, 17 of them claimed that it could be transmitted through “witchcraft”, 27 of the respondents recognised “sharing of personal items like towel and blade” and 2 others mentioned “blood transfusion” as one of the modes of transmission with only one respondent claiming STDs can be transmitted through “food”. A total of 58 out of the 60 respondents recognised.

| Item | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Do you know what STDs? | ||

| Yes | 50 | 83.3 |

| No | 10 | 16.7 |

| How can STDs be transmitted? | ||

| Through sex | 48 | 96 |

| Witchcraft | 17 | 34 |

| Through food | 1 | 2 |

| Sharing of personal items like towel, blade etc. | 27 | 54 |

| Others | 2 | 4 |

| Which of these are examples of STDs? | ||

| HIV | 58 | 96.7 |

| Gonorrhoea | 47 | 78.3 |

| Chlamydia | 5 | 8.3 |

| Syphilis | 36 | 60 |

| Heptatitis B | 7 | 11.7 |

| Genital Wart | 12 | 20 |

| Can STDs be cured? | ||

| Yes | 44 | 73.3 |

| No | 16 | 26.7 |

Table 5: Respondents knowledge on STDs including HIV.

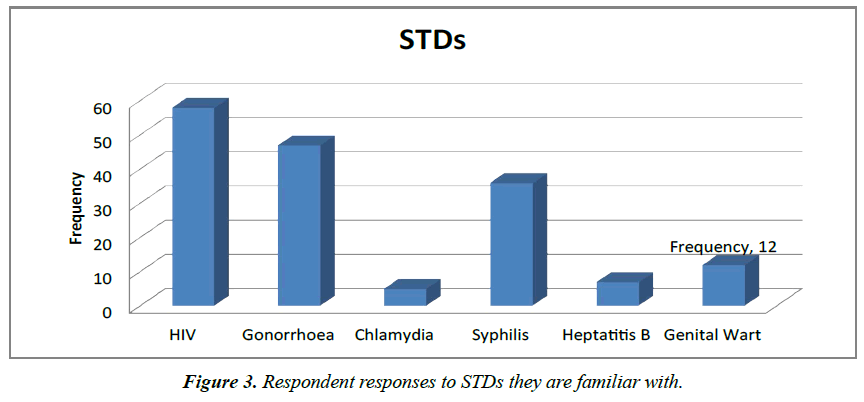

“HIV” as being example of STDs. The second most known STD was “gonorrhea” followed by “syphilis” and “genital wart” with the least known STDs in descending order being “hepatitis B” and “chlamydia”. Overall, 44 representing 73.3% of the respondents claimed that STDs could be cured whilst the remaining claimed that it could not be cured.

Figure 2 shows the detail analysis on respondents’ knowledge on STDs including HIV whilst Figure 3 shows respondents’ responses to STDs they are familiar with. During the focus group discussion, respondents were asked whether they knew how to prevent STDs or pregnancy during their first sex experience. Most of them claimed to be ignorant on how to prevent STDs or pregnancy during their first sex experience. A respondent stated that:

“Before I had my first sex experience, I had no prior knowledge about it. It was someone who educated me on that after. She even advises me to go for family planning.”

Even with those who knew before engaging in sex, clarity was being made by one of them on the fact that they refused to be protected. The respondent went further to assert that:

“All what they are saying is right, being the first time you are going to experience sex, you will be rushing and so even if you know about condom, you will not think about it. At that time it will just be a matter of pushing the penis into it. You will never think about wearing a condom and that is when if you are not lucky you will be in trouble.”

Assessing their knowledge on the best way to prevent pregnancy and STDs revealled many facts, misconceptions and beliefs. Some cited abstinence and condom usage as the best way of preventing pregnancy and STDs whilst others held and supported some of these assumptions. Two of the respondents continued separately on the fact that:

“I know that there is a medicine for girls to use to prevent pregnancy when having sex, they call it P2 or you the man and the woman can take chill water just before sex, when it happens like that it will reduce the quantity of sperms that will come out of the man and the few that will enter the woman will be flushed out as the woman urinate right after the sex and no pregnancy will occur.”

“Either we use condom or bath just after sex so that any disease around us will be washed away and render us clean. If we do that we will not get any disease.”

Causes of Poor SRH

Identifying and understanding the cause of an issue is part of the solution process. In view of this, the causes of poor SRH health knowledge were critically examined using both questionnaire and focus group discussion. As shown in Table 6, 47 and 37, out of the 60 representing 78.3% and 61.7% of the respondents who responded to the questionnaires expressed their opinion that they are not permitted to freely talk on sex issues by their religion and their community respectively.

| Categories | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Does religion permit adolescents to talk about sex freely? | Yes | 13 | 21.7 |

| No | 47 | 78.3 | |

| Total | 60 | 100 | |

| Can adolescents discuss sex or SRH issues in the community freely? | Yes | 23 | 38.3 |

| No | 37 | 61.7 | |

| Total | 60 | 100 | |

| Last time they heard or learnt something on SRH? | Days | 10 | 16.7 |

| Months | 27 | 45 | |

| Year(s) | 23 | 38.3 | |

| Total | 60 | 100 | |

| Where they hear or learnt something on SRH the last time? | School | 40 | 66.7 |

| Media | 14 | 23.3 | |

| Home | 5 | 8.3 | |

| Others | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Total | 60 | 100 |

Table 6: A Table showing respondents’ responses on the causes of poor SRH.

Similar responses were identified during focus group discussions. Most of them argue that it is not accepted to stand in public and discuss issues of SRH especially, issues relating to sex with friends at that tender age and that the elderly would not tolerate or accept that as stated by some of the respondents and was being supported by others. Two of the respondents buttress this fact by stating:

“No, it is not our tradition for us to talk about that and our elders would not even permit that.”

“No, as at now we are not allowed to talk on issues of sex with our peers, our elders in Komenda do not permit us to stand in public and talk about those issues.”

“No we cannot even feel free and ask our parents, we can only feel free and ask our friends and we can only do that when the adults are not around. Unless we the “boys boys” meet in our playing grounds.”

The few others who were of the view that they could talk on sexual issues with their friends acknowledged the fact that they were faced with limitations. A respondent buttressed that:

“It depends on when and where you are and who you are standing with, for example in youth club you can discuss about it, sometimes it is not in a bad way so you can ask for explanation so you can have knowledge about it.”

Another respondent indicated that:

“Yes we can, just that if you want to do that you have to go to secret place, it is not respect to talk about it when there is elderly around.”

Again, when being asked the last time they heard or learnt something on SRH, 23 of the respondents alleged that they had heard or learnt it a year or some years ago, 27 indicated month(s) ago and the remaining just few days ago. As of the place they heard it, 40 out of the 60 claimed they heard it from “school” (66.7%) followed by “media” (23.3%), “home” (8.3%) and “religious gathering” (1.7%).

Methods/Sources of SRH information

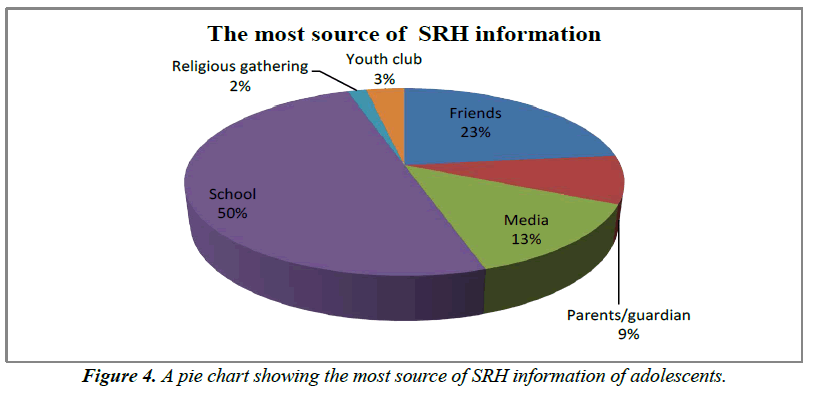

Participants claimed to have many sources of SRH information as depicted in Table 7 through the survey. However, as depicted by Figure 4 the most source of SRH information for the study participants was found to be school (50%) followed by friends (23.3%), media (113.3%) and parents (8.3%).The least most source of information for the study participants were found to be youth club (3.3%) and Religious gathering (1.6%). 39 representing 65% of the quantitative survey participants were ignorant about organisations or facilities in the community that offers SRH services.

| Item | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Where they have been getting SRH information from | Friends | 42 | 70 |

| Parents/guardians | 16 | 26.7 | |

| Media | 44 | 73.3 | |

| School | 51 | 85 | |

| Religious ground | 4 | 6.7 | |

| Youth club | 25 | 41.7 | |

| Where they most often get SRH information from | Friends | 14 | 23.3 |

| Parents/guardian | 5 | 8.3 | |

| Media | 8 | 13.3 | |

| School | 30 | 50 | |

| Religious gathering | 1 | 1.6 | |

| Youth club | 2 | 3.3 | |

| Do you any organisation that offer SRH services | Yes | 21 | 35 |

| No | 39 | 65 | |

| Who they will prefer to discuss SRH issue with | Parent/guardian | 34 | 56.7 |

| Religious leader | 3 | 5 | |

| Health professional | 31 | 51.7 | |

| Teacher | 13 | 21.7 | |

| Peers | 31 | 51.7 | |

| Where they will prefer to learn about SRH with peers | School | 43 | 71.7 |

| Media | 4 | 6.7 | |

| Health facility | 26 | 43.3 | |

| Youth club | 25 | 41.7 | |

| Religious ground | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Home | 14 | 23.3 |

Table 7: A Table depicting the method/sources of SRH information.

As to whom they would prefer to share SRH issue with, 34 of the respondents considered their parents or siblings as one of the entities they would want to discuss SRH issue with, 31 of them were also found to prefer to share SRH issues with their peers and health professionals. Only few were willing to share SRH issue with their Teachers and religious leaders. Again, 43 of the participant chose school as one of the places they would prefer most to learn about SRH with their peers followed by health facility and youth club thus 26 and 25 participants respectively. Only 4 and 1 participant liked media and religious gathering respectively.

The study revealed during focus group discussions that most of the adolescents’ respondents preferred to discuss SRH issue with their parents/guardians as one of the male respondent asserted:

“I will tell my parents, since they are the ones who gave birth to me and they have taken care of me to grow up. I will never be ashamed to report to them.”

Others also argued that they were shy of their parents and so they would either tell their friends or go to the drug store to seek help. In support of this claim, one of the female respondents alluded that:

“For me I am shy of my parent so I will tell my friends.”

However, as discussions went on, emphasis was laid on the fact that it depends on the type of SRH issue to be discussed. Being supported by the other female respondents, two of the female respondents emphasised separately that:

“If it happens that I woke up now and experience any changes in my reproductive organ, the first person I will tell is my boyfriend.”

“Not all things should be told to a friend especially the sensitive ones. They will even ridicule you with it in the future.”

As to where they would prefer most to learn on SRH, most of them cited school as the best place to learn or receive knowledge on SRH. One of them made a remarkable comment that:

“To me, I wish they will remove core mathematics and replace it with it. So that it will become one of the core subject, because you are always told to find X but I don’t see it’s relevant in my life, this is what will help my life.”

One of the female respondents when discussing said:

“I heard the government wanted to add it to the subject but the parents refuse, but if it is true then they have committed a sin and a crime because they want the children to go wayward and continue getting pregnant anyhow. It should be allowed to be taught in school because most people don’t have any idea about it and our parents themselves don’t know much about it.”

Others also proposed youth club and where the public used to gather as one of the best places to receive knowledge on SRH aside school. Most of them also agreed that it would be best to discuss SRH issue in group as this will enable them to learn and share experiences with each other. This will not also let others perceive one as a “bad boy” whom they are giving some sort of advice especially when engaged individually. In support of this assertion was made by two male respondents that:

“When they engage only me, it will be like they are offering only me advice and I will never agree, when we are in group then I will agree because they are offering all of us advice and I will be Ok.”

“Group is nice, everyone will share idea, and so group is better that individual.”

Others also recommend that the information be shared through media as they will be able to reach more people since the media has become a common place for people including adolescents to share and receive information. Buttressing this opinion, one female respondent opined that:

“They should spread the message in social media, since everyone nowadays goes there.”

Socio-economic impact of poor SRH knowledge

The socio-economic impact of poor SRH knowledge was assessed as shown in Table 8, the results depicted that 55 out of 60 of those who responded to the questionnaires acknowledged the fact that there were indeed social consequences of poor SRH knowledge on the adolescents with most giving reasons such as adolescent teenage pregnancy, school dropout leading to abandonment by parent and contracting infections or diseases. Exploring further with the focus group discussions reveals greater intensity of poor SRH on the social life of the adolescents. It was found out that the social effect of poor SRH goes beyond the adolescent and it just not a matter of just getting pregnant, dropping out of school or contracting diseases, the consequences are deep as one female who dropped out of school explained:

| Item | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Does poor SRH have any consequences on adolescent social life? | Yes | 55 | 91.7 |

| No | 5 | 8.3 | |

| Total | 60 | 100 | |

| Does poor SRH have any consequences on adolescent economic life? | Yes | 47 | 78.3 |

| No | 13 | 21.7 | |

| Total | 60 | 100 |

Table 8: Respondents responses on socio-economic impact of poor SRH knowledge.

“Now a days if it happened that one teen impregnate the other, both families will be disappointed in you. You will receive a lot of insults from friends and family, you will never be happy in life, you will not feel ok approaching friends or moving to public places. Sometimes you may think of ending it all. You will be stigmatized and same is true if you contract HIV, in Komenda here no one will be willing to mingle with you and you will tarnish your image for the rest of your life time.”

Another female also alleged:

“In this community, many may like you but immediately you get pregnant, all of this love one’s will hate you. You will wonder why someone who loves you has just turned your enemy. Your parents will not also relate well with you because what they want you to be you didn’t humble yourself, you did not become what they want you to become. You have rushed and got it wrong.”

It was also found out that the social effect of poor SRH knowledge is not just sometimes inimical to entire life of the adolescent alone but also to the family in which the adolescent belongs to. To personalise this effect of poor SRH on the family, a female respondent eluded that:

“we are three and because of financial problems the other two have to stop schooling to support me to continue schooling, so if it happen that I get pregnant, it will really hurt them.my mother may drink poisons as she always says and die because of it.”

Others went ahead to also discuss the very daily decisions that will be affected as a result of poor SRH knowledge as indicated by a male respondent that:

“If you don’t have any knowledge in what we are discussing, it will affect your daily decisions. You will one day surely impregnate someone or contract infection.”Similarly, 47 of the survey participants as shown in Table 8 also recognised that poor SRH knowledge had some level of economic effect on them. Prominent reasons given were not being able to afford drugs and feed well when they contract STDs or get involve in pregnancy. Others also cited poverty and inability to work.

When explored further during the focus group discussions, a deeper insight of the economic impact of poor SRH was being revealed. The custom monetary imposed burden is what makes the economic impact very worse as alleged by one of the focus group participants that:

“In our community, I mean Komenda, impregnating someone’s child is really a big issue, you can never got scot free. We call something “nkwaseabu sika” (a traditional Fante term used to denote penalty paid as compensation to the one being impregnated family) they will call your parent and charge you. They said they have to charge you because you have stolen someone gift. This is the monetary issue that can bring burden to you and your family, I know a friend who was charged five thousand cedi. If you the child doesn’t have and the family too do not also have, it will bring conflict between you and your family and the other family and can land you in prison.”

One of the participants also made important submission depicting why some of them involved themselves in activities that the laws and traditions of the society did not permit. He stated that:

“In this our current life, money is needed for everything, if it happen that I impregnate someone and since my parent do not have money, I will surely be troubled. What I will not do ordinary is what I am going to do so that I can cater for the girl.”

In the same vein others also moaned on the very financial crisis that they are bound to encounter when they get themselves pregnant. One of the female participants who has given birth before and as a result led to parent abandonment shared her experience in anguish:

“As of the monetary aspect I do not want to hear or talk about it, don’t even think about the one who impregnated you, everyone will turn their back on you. You will have to do everything for yourself. You it ok let me end here.”

It was clear from the discussions that indeed poor SRH knowledge does not only have very bad consequences on the adolescents’ immediate life but goes far beyond it and that there is necessity for action to be taken if the future of these adolescents is to be guaranteed.

Discussion

The objectives of the study were to examine the general sexual and reproductive knowledge, identify causes of poor SRH knowledge, methods/sources of SRH knowledge and the socioeconomic impact of poor SRH knowledge among adolescents in the Komenda community in the central region of Ghana. This sub section outlines the discussions of the findings presented in this section with respect to study objectives.

Knowledge on sexual and reproductive health in general

Findings indicated that adolescents had limited comprehensive knowledge on what SRH is all about as defined by authorities. For example, only less than a third of those who claimed to know what SRH entails were able to recognise contraceptives as being part of broad SRH domain. United Nations, 1995 recognised human rights as being one of the major parts of the SRH domain yet only a third of the respondents were able to recognise it as such and same is true for abortion. This may be as a result of the fact that the subject matter is not well taught in schools in its systematic and comprehensive nature, thus some sections are being taught. The manner in which some aspects of the subject matter are taught in school confirms the reason why a significant of them were able to recognise sex education and STIs as such since most of the respondents are in schools (68.42%) or have been students before. This of course is in line with findings of Ivanova et al. [12] study on adolescents in which adolescents pointed out inadequacies related to the range of SRH topics taught in school, which were usually limited to abstinence with very little information on contraceptives.

The various other sources that offer them SRH knowledge may also not offer broad services concerning the subject matter but based on needs and what they the service providers consider to be relevant. Health is broad and same is true for SRH, we cannot achieve that complete state of well-being without adequately meeting the broader conceptualisation of health as defined by WHO (1948) as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” Same is true for SRH, adolescents cannot grow up safe, healthy, and ready to succeed when their knowledge and skills to make healthy decisions about their sexual and reproductive health is fragmented. There is therefore, the need to recognise all areas of SRH as equally important so as to project actions to inculcate in the adolescents the very comprehensive knowledge and skills they need in order for them to make smart and healthy choices concerning their sexual and reproductive health so as if possible achieve that ideal state of well-being with regards to sexual and reproductive health.

Knowledge on contraceptive and pregnancy’

Adolescents’ knowledge on contraceptives found in the findings of the result of this study was quite comparable to their counterparts in other parts of the world. Eliason et al. [13] found that a little over 90% of young women of reproductive age knew at least one method of modern contraceptives as compared to this study where 90% claimed to understand what contraceptives are used for and where all the respondents understood at least one type of contraceptive (condom). It is also in conformity to the GDHS 2014 finding that knowledge of contraceptives among young females and adolescents has been relatively high. Among 15-19 year olds, knowledge of any form of contraceptive has improved upon significantly.

The findings on the best contraceptive to prevent pregnancy also match with Ayalew et al. [14] findings that is, 50% versus 47.7% respectively. Even though the study did not use quantitative approach to explore contraceptives usage, the insights revealed in the focus group discussions explained why contraceptive usage is low as reported in the finding of GDHS, and Ivanova et al. [13] as clearly observed in the discussions of the female participants when being asked whether their guys use condom during sex. In support of the facts that they and their guys are not willing to use contraceptive, two of the female respondents separately alleged that:

“Will you want to eat toffee with the rubber on, I know my boys even if you give them condoms they will never use it, they prefer it raw, we the ladies sometimes have to protect ourselves by taking pills.”

“I have not given birth even if I have; I will never do family planning. I will not do that so that if i don’t give birth in the future, no one will say is my grandmother sitting somewhere who is responsible.”

Such statements stress on the fact even though they knew and have options in choosing contraceptives to prevent pregnancies, however, they are not willing, possibly this may be due to the misconceptions they hold about contraceptives and the perceive side effect of using contraceptives as revealed in the findings, for example, a significant 65% of the participants responded that there is serious effect associated with the use of contraceptives. Access to contraceptives seems to be not a problem in this context.

It will also be a fallacy to argue that since most knew at least one contraceptive, so they have complete knowledge on what contraceptives are and what they are appropriately used for. The finding of the study indicates that a significant proportion of the study participants, more than a third thought that contraceptives are also used for abortion; these misconceptions may arise because significant percentage of the respondents receive SRH information from wrong sources such as friends and sometimes the media. Even though acquisition of knowledge or information does not necessary guarantee the application and usage of that knowledge by the individual, one cannot also make any informed or smart decision without accurate and reliable information or knowledge. The health belief model for example posits a cue or trigger that is necessary for prompting engagement in health-promoting behaviours by the individual, this cue include information from peers and the media. There is therefore, the need to control such erotic information sources from the media and related sources.

Knowledge on STDS including HIV

Findings of the result depicted that a very significant number of the study participants were very conversant with STDs. 50 out 60 of the participants representing 83.3% of those who responded to the questionnaire claimed to know what STDs are. 48 participants representing 96% of the respondents who knew what STDs were indicated that it can be transmitted through sex. This of course do not deviate from the research conducted on adolescents in secondary school in Nigerian which found out that majority of the adolescents had good knowledge on STIs and their mode of transmission. The study is also in conformity to the findings of GDHS, (2014) which reported that nearly all the participants had heard about HIV thus this study found out that 96.7% of the participants knew HIV as an STD. The study also goes a long way to reflect the findings of Eaton et al. 2010 and Hassan et al. 2015, who found out that generally adolescents wer