Research Article - Current Pediatric Research (2021) Volume 25, Issue 12

Effect of arm ergometry training on pulmonary function in children with down syndrome

Reham AA Abouelkheir1,2, Mohamed E Khalil2, Ashwag Saleh Alsharidah3, Hanaa Mohsen Abd Elfattah4*

1Department of Physical Therapy for Pediatrics and Surgery, College of Physical Therapy, Misr University for Science and Technology, Giza, Egypt

2Department of Physical Therapy, College of Medical Rehabilitation, Qassim University, Qassim, Saudi Arabia

3Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, Qassim University, Qassim, Saudi Arabia

4Department of Physical Therapy for Pediatrics and Pediatric Surgery, College of Physical Therapy, Badr University in Cairo, Cairo, Egypt

- Corresponding Author:

- Hanaa Mohsen Abd Elfattah

Department of Physical Therapy for Pediatrics and Pediatric

Surgery

Badr University in Cairo

Cairo, Egypt

E-mail: Hanaa753@gmail.com

Accepted date: 23rdDecember, 2021

Abstract

Objective: The aim of the current research was to evaluate the efficiency of upper-limb aerobic exercise (arm ergometry) in improving pulmonary function in Down syndrome children. Methods: This study included thirty Down syndrome children (boys and girls). All participants were randomly separated into two groups of equal size (A&B). Group A received traditional chest physical therapy while Group B received an arm ergometry training program. A Discovery spirometer was used to assess pulmonary functions both Forced Expiratory Volume (FEV1) and Peak Expiratory Volume (PEV) was measured. Results: There were no significant differences between the two groups before the treatment program in all of the evaluated parameters. Post-treatment data’s showed significant improvements in group B compared to group A (P < 0.05). Conclusion: Based on the findings of this study, it can be stated that the arm ergometry training program which used in this study is an effective therapeutic program that can be used to improve pulmonary functions in children with Down syndrome.

Keywords

Arm ergometery, Down syndrome, Chest physical therapy, Pulmonary function.

Introduction

Down Syndrome (DS) is one of the most predominant chromosomal abnormalities, occurring in one out of each 800 births [1,2]. DS comprises a series of congenital disabilities such as mental retardation, obesity, typical facial features, heart disorders, pulmonary infections, visual ailment, and numerous other health difficulties [3,4] .

Physical impairments typically associated with DS, including muscle weakness, circulatory and pulmonary anomalies were proposed to explain their low level of physical efficiency [5]. Heart defects, lung hypoplasia, hypotonia, and narrow nasal and oral cavities are among the anatomical changes linked to DS, which can restrict their pulmonary function [6].

Among children with DS, cardiopulmonary problems are the principal source of illnesses and hospitalization [7,8]. Chronic lung infections, middle ear infections, and persistent tonsillitis are also more common in DS children [8]. Children with DS who do not suffer from pulmonary anomalies, inherited heart defects, and endocrine defects are typically experienced restriction in their normal daily work routine. These children struggle with simple tasks when compared to their peers who are normal [9-11].

Children with DS are more prone to getting pulmonary dysfunctions. It occurs due to several causative aspects, including immunological failure, poor muscle tone, and respiratory muscle neurological dysfunction that contribute to low capacity with reduced ventilatory pump. Immune dysfunction may potentially have a part in the increased incidence of respiratory issues found in DS patients [12]. Pulmonary function tests provide an objective evaluation of pulmonary function and are essential in determining the impact of cardiopulmonary disease pathology and treatment outcomes [13]. A vital part of pulmonary rehabilitation is chest physical therapy. Treatment frequency must be adjusted to the seriousness of the disease and the condition of the airway secretions [14]. Respiratory problems are associated with developmental, musculoskeletal, or ventilatory pump impairment. Pulmonary rehabilitation aids in the restoration or maintenance of cardio-respiratory functions in DS patients [15]. Upper and lower limb aerobic exercise activities are essential components of any pulmonary rehabilitation interventions.

Aerobic training is essential for pulmonary rehabilitation because it helps patients with chest diseases enhance their functional capability [16,17]. Aerobic activity involves treadmill walking, swimming, arm ergometer training, and climbing stairs, cycling, running, and rowing [18]. In patients with DS, a mixture of gradual strength and aerobic exercise can significantly influence physical performance than aerobic exercise by itself [5].

Traditional chest physical rehabilitation includes respiratory exercises, postural drainage, therapeutic percussion, and aerobic exercise, which assist the patients in enhancing their life quality, improving their ability to conduct everyday tasks safely, and reducing the usage of pharmacological medicine [19]. This research evaluated the effectiveness of upper-limb aerobic training in DS children.

Material and Methods

Study design

A single-blind, randomized clinical trial was conducted at the national institute of neuromotor system and Badr university in Cairo.

Randomization

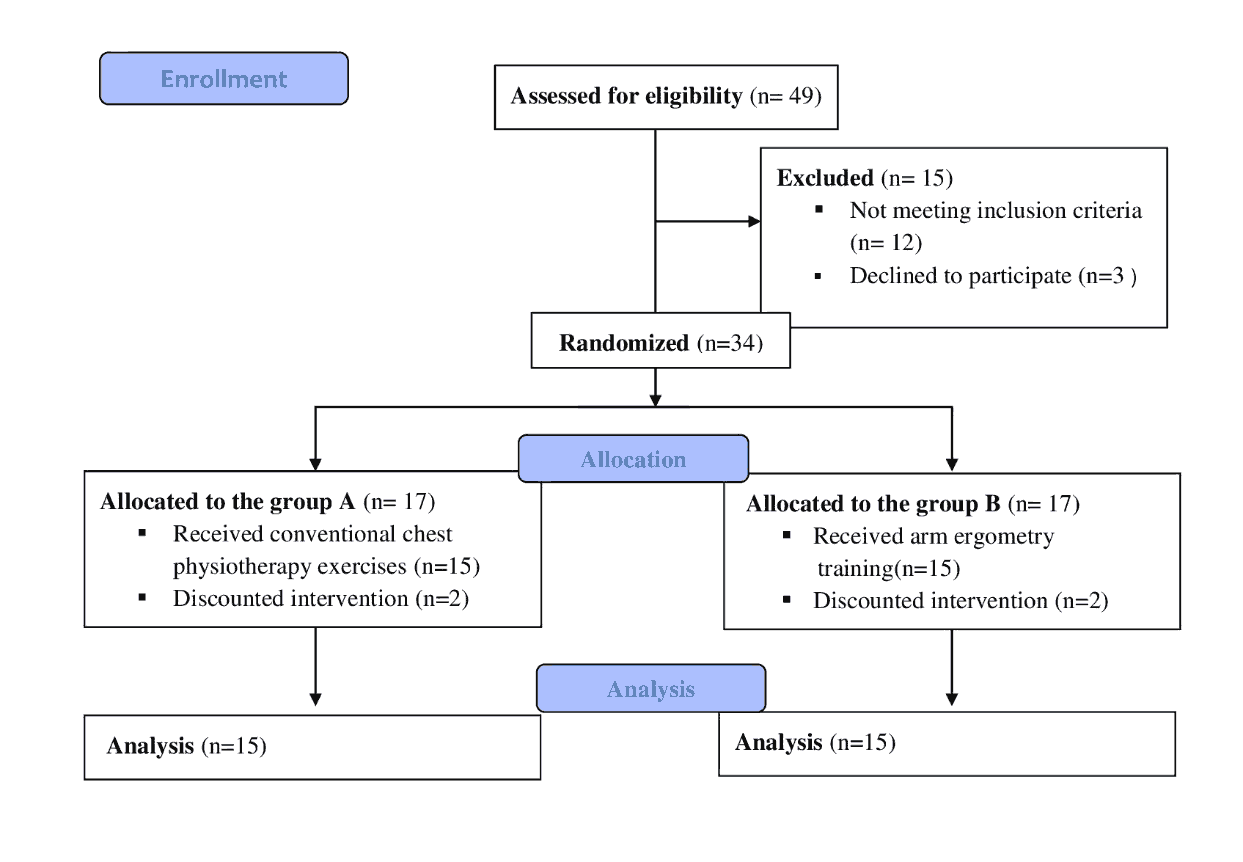

49 children with DS were chosen for our study; 12 did not match the eligibility criteria and were excluded, and 3 refused to participate. Participated children were randomly allocated to any of the two groups after baseline measurements: A or B. The children were given a number in order from 1 to 30. After that, 17 children were randomized to each category at random using online graph pad software. Researchers responsible for evaluations were blinded to participants’ allocation. Figure 1 depicts the experimental design.

Participants

Thirty DS children (19 boys and 11 girls) of both genders were able to comprehend and follow directions. The participants' age ranged from ten to fourteen years. Children could not participate if they had any of the following conditions. 1: Anomalies of the vasculature. 2: Participating in sports of any kind. 3: Moderate to severe asthma. Before gathering the data, the goals, techniques, and benefits were carefully described to the children's parents. Parents were offered the option of providing a written agreement for their children to participate in the contemporary research. The declaration of Helsinki criteria for human studies was followed throughout this study. The faculty of physical therapy, Cairo university ethics review board, gave their approval to the project and it was registered at clinicaltrail.gov with registration number: NCT05068570.

Outcome measures

Discovery spirometer-model: Discovery MPN: C09020-022-99 country/region of manufacture (United States) was used to test pulmonary functions, discovery spirometer was used to measure forced expiratory volume after 1 second "FEV1" and Peak Expiratory Flow Rate "PEFR" pre and post-treatment for 14 weeks at 3 times per week.

Weight and height scale: It was used to determine the child's weight (in kilograms) and height (in centimeters), which are required for the "discovery spirometer" to function properly.

Interventions

Group A received a respiratory physical therapy protocol that included respiratory exercises and incentive spirometer training for 30 minutes/session. In contrast, Group B received an arm ergometry training protocol (the Magneciser pedal exercise, model 803, from the United States, was used). The following protocol was applied, as shown in Table 1 [20].

| Weeks | Description |

|---|---|

| 01-Apr | The children in this group were taught to cycle at a pace of 15-25 cycles per minute without resistance for 2 minutes of exercise followed by 1 minute of rest for a total of up to 10 minutes. |

| 05-Sep | For a total of up to 12 minutes, children in this group were trained at a pace of 25-35 cycles per minute without resistance for periods of 2 minutes of exercise followed by 1 minute of rest. |

| Oct-14 | For a total of up to 14 minutes, children in this group were trained at a pace of 35-45 cycles per minute without resistance for periods of 2 minutes of exercise followed by 1 minute of rest. |

Table 1. Arm ergometer training protocol (Group B).

5 minutes before beginning the exercise and for 5 minutes after they're finished: as thoracic mobility exercises and stretching exercises for the upper and lower extremities were used to warm up and cool down. Both groups were trained four days a week for 14 weeks.

Study sample

The pre-study sample size calculation was completed through a pilot study via G*power statistical software (version 3.1.9.2; Franz Faul, University of Kiel, Germany). For means differences between two independent means (two groups), α=0.05, β=0.2 was and revealed that the appropriate sample size for this study was not less than 24 children. We recruited up to 34 children to account for the possible withdrawal rates.

Statistical analysis

The general attributes between groups were evaluated through the t-test, mean, and standard deviation. The comparison between pre and post-scores within and between groups was analyzed using paired and unpaired t-test. Statistical significance was detected as (P<0.05). All statistical computations were performed using the computer program SPSS (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) version 20.

Results

There were no significant differences in the demographic data between both groups as shown in Table 2 between the two groups (p<0.05).

| Subject characteristics | Mean ± SD | P-value | |

| Age/year | Group A | 11.6 ± 1.3 | |

| Group B | 11.4 ± 1.1 | 0.127a | |

| Weight/Kg | Group A | 29.8 ± 2.6 | |

| Group B | 30.1 ± 2.5 | 0.374a | |

| Height/m | Group A | 1.35 ± 0.035 | |

| Group B | 1.38 ± 0.022 | 0.453a | |

Table 2. Subject’s data (Group A), (Group B). SD: Standard Deviation and p-value stands for the degree of significance in a t-test. a: Comparison between groups.

The pretreatment results of this study showed that there were no significant differences (p>0.05) in all measured parameters among both groups of patients in the pulmonary functions as indicated in Table 3 which revealed that both groups were matched in the measured variables at the start of the study and the pulmonary functions (FEV1, and PEFR) were below the predicted values for these patients in relation to their ages, weights and heights. The post treatment findings showed that, there were enhancement in both groups of the participants’ pulmonary function "FEV1, PEFR" represented by significant differences between the pre-treatment and post-treatment pulmonary functions after 14 weeks as indicated in Table 3 (p<0.05).

| Pre-treatment | Pa-value | Post-treatment | Pa-value | Pre vs. Post | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | Group A | Group B | Group A | Group B | |||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Pb-value | Pb-value | |||

| FEV1 (L) | 1.213 ± 0.10 | 1.198 ± 0.09 | 0.198 | 1.35 ± 0.08 | 1.4 ± 0.03 | 0.008 | 0.065 | 0.003 |

| PEFR (L/Min) | 181.5 ± 11.2 | 179 ± 11.18 | 0.41 | 181.5 ± 11.2 | 187 ± 11.6 | 0.047 | 0.058 | 0.006 |

Table 3. FEV1 (L) and PEFR (L/min) statistical analysis for both groups. SD: Stands for Standard Deviation; P-value: Stands for the level of SD; p-value stands for the level of significance; a: Comparison between groups, b: Comparison within groups.

Discussion

The effectiveness of arm ergometry training and respiratory physical therapy in improving pulmonary function in DS children was examined in this study. In the pre-treatment outcomes of this investigation, there were no significant differences between both groups of patients regarding lung function. As a result of these findings, both groups started the experiment with equal measurements and lung functioning. The participants pulmonary functions were lower than expected for their ages, weights, and heights.

Improved post-treatment results in Group A may be due to increased alveolar ventilation and decreased dead space ventilation [21]. It may also be due to the strengthening of respiratory muscles that was proven by Rutchik et al. who concluded that an improvement in pulmonary function and a decrease in dyspnea were most likely due to the strengthening of respiratory muscles. Also, Darnley et al. stated that strengthening respiratory muscles improves exercise ability and alleviates breathlessness symptoms [22,23]. Bott 21 reported that chest physical therapy improves deep diaphragmatic breathing and expands collapsed areas by providing visual feedback for diaphragmatic exercise.

The improved post-treatment results of Group B can be related to enhanced skeletal muscle development, endurance, and oxidative capacity. The body's need for oxygen increases during aerobic exercise, so the respiratory system must increase oxygen supply to the active muscles. As a result, aerobic exercise increases respiratory system efficiency, raising oxygen supply [24]. According to the findings, treadmill training, swimming, bicycling, and other types of aerobic exercise offer an appropriate stimulation to enhance ventilatory functions [25]. Similar results have been stated by other researchers Normandin et al. and Rochester who stated that after the aerobic exercise program, patients with obstructive pulmonary disease had improved pulmonary functions and exercise capacity [26,27].

Aerobic exercise training increases oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production, and the lungs respond by maintaining a stable blood level of these gases in the bloodstream. Lactic acid, which is produced by working muscles, starts to circulate in the bloodstream. This is referred to as the lactate threshold. Lactic acid is the source of metabolic acidosis. The lungs interact with lactic acidosis during aerobic activity by increasing ventilation, decreasing arterial PCO2, and maintaining normal arterial blood pH. The respiratory system fully adapts to the pH effects of lactic acid during exercise [28].

During aerobic exercise, the lungs must deliver extra oxygen to the working muscles via the bloodstream due to the body's increased oxygen demand. Increased breathing depth improves the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the lungs. Consequently, frequent exercise enhances the lungs' oxygen-supply capacity [29]. There was no follow-up with the children to ensure that the improvements were maintained over time, which is one of the study's limitations [30,31].

Conclusion

This study's arm ergometry training technique could benefit children with DS aiming to improve their pulmonary functions. According to our findings, the arm ergometer training program should be used in schools for children with DS as a part of their schedule. Future researches should be conducted to monitor the influence of ergometry on physical strength, lifestyle, fatigue, pain, muscle strength, and health-related quality of life. The efficacy of aerobic exercise in DS patients and possible side effects should be properly evaluated.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude to all patients and their parents who took part in the study.

Author Disclosures

This research got no funding. The authors declare no financial ties to or engagement with any commercial entity that has a direct financial interest in any of the topics or materials covered in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Abouelkheir RA, Abd-Elfattah HM, Khalil ME, Alsharidah AS. Methodology: Abd-Elfattah HM, Khalil ME. Formal analysis: Khalil ME. Writing original draft: Khalil ME, Alsharidah AS. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

References

- Roizen NJ, Patterson D. Down's syndrome. The Lancet 2003; 361(9365): 1281-9.

- Ulrich DA, Ulrich BD, Angulo-Kinzler RM, et al. Treadmill training of infants with Down syndrome: Evidence-based developmental outcomes. Pediatrics 2001; 108(5): e84.

- Pitetti KH, Rimmer JH, Fernhal B. Physical fitness and adults with mental retardation. Sports Med 1993; 16(1): 23-56.

- Winnick JP, Porretta DL. Adapted physical education and sport. (6th edn). Human Kinetics 2016.

- Dodd KJ, Shields N. A systematic review of the outcomes of cardiovascular exercise programs for people with Down syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 86(10): 2051-8.

- Andriolo RB, El Dib R, Ramos L, et al. Aerobic exercise training programmers for improving physical and psychosocial health in adults with Down syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 12(5): CD005176.

- Hilton JM, Fitzgerald DA, Cooper DM. Respiratory morbidity of hospitalized children with Trisomy 21. J Paediatr Child Health 1999; 35(4): 383-6.

- Doull I. Respiratory disorders in downs syndrome: Overview with diagnostic and treatment options. Down's Syndrome Medical Interest Group 2002.

- Fernhall B. Limitations to physical work capacity in individuals with mental retardation. Clin Exerc Phys 2001; 3: 176-85.

- Baynard T, Pitetti KH, Guerra M, et al. Age-related changes in aerobic capacity in individuals with mental retardation: A 20 years review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008; 40(11): 1984-9.

- Pitetti KH, Climstein M, Mays MJ, et al. Isokinetic arm and leg strength of adults with Down syndrome: A comparative study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1992; 73(9): 847-50.

- Marder E, Dennis J. Medical management of children with Down's syndrome. Curr Pediatr Res 2001; 11(1): 57-63.

- Batshaw ML, Pellegrino L, Roizen NJ. Review of the month. Learn Disabil Pract 2008; 11(3): 15-25.

- Weinberger S. Pulmonary anatomy and physiology: The basic in principle of pulmonary medicine (4th edn). 2004; pp:1-19.

- Gaowgzeh RA, Chevidikunnan MF, Khan FR. Impact of pulmonary rehabilitation program on respiratory function and exercise tolerance in subjects with Down syndrome. IOSR-JDMS 2017; 16(2): 68-72.

- Satshanna S, Teresa G. Pulmonary rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 99(9): 769-774.

- Larson JL, Covey MK, WIrtz SE, et al. Cycle ergometer and inspiratory muscle training in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit 1999; 160(2): 500-7.

- Cheng YJ, Macera CA, Addy CL, et al. Effects of physical activity on exercise tests and respiratory function. Br J Sports Med 2003; 37(6): 521-8.

- Verrill D, Barton C, Beasley W, et al. The effects of short-term and long-term pulmonary rehabilitation on functional capacity, perceived dyspnea, and quality of life. Chest 2005; 128(2): 673-83.

- Bernasconi SM, Tordi N, Ruiz J, et al. Changes in oxygen uptake, shoulder muscles activity, and propulsion cycle timing during strenuous wheelchair exercise. Spinal Cord 2007; 45(7): 468-74.

- Bott J. Respiratory care: A very necessary specialty in the 21st century. Physiotherapy 2000; 86(1): 2-4.

- Rutchik A, Weissman AR, Almenoff PL, et al. Resistive inspiratory muscle training in subjects with chronic cervical spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998; 79(3): 293-7.

- Darnley GM, Gray AC, McClure SJ, et al. Effects of resistive breathing on exercise capacity and diaphragm function in patients with ischemic heart disease. Eur J Heart Fail 1999; 1(3): 297-300.

- Wouters EF. Approaches to improving health status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: one or several? PATS 2006; 3(3): 262-9.

- Quell KJ, Porcari JP, Franklin BA, et al. Is brisk walking an adequate aerobic training stimulus for cardiac patients? Chest 2002;122(5):1852-6.

- Normandin EA, McCusker C, Connors M, et al. An evaluation of two approaches to exercise conditioning in pulmonary rehabilitation. Chest 2002; 121(4): 1085-91.

- Rochester CL. Exercise training in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Rehabil Res Dev 2003; 40(5): 59-80.

- Sharaf MA, Hashem HE, Ahmed WO. Simultaneous use of factor XIII and fibrin degradation products in diagnosing early cases of NEC and neonatal sepsis. Journal of Scientific Research in Medical and Biological Sciences 2021; 2(4): 1-10.

- Farid R, Ebrahimi A, Khaledan A, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise training on pulmonary function and tolerance of activity in asthmatic patients. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol 2005; 4(3): 133-8.

- Alhusam S. clinical conditions and risk factors of acinetobacter baumannii producing metallo beta-lactamases among hospitalized patients. Journal of Scientific Research in Medical and Biological Sciences 2021; 2(4): 11-17.

- Emiel F. Approaches to improving health status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PATS 2006; 3: 262-269.