Research Article - Journal of Clinical Nephrology and Therapeutics (2022) Volume 6, Issue 6

Drug induced acute nephritis mimicking acute abdomen: biopsy-proven a case report

Sinan Kilic*Depatmant of Pediatric Surgery, Gebze Yuzyil Hospital, Gebze, Kocaeli, Turkey

- *Corresponding Author:

- Sinan Kilic

Depatmant of Pediatric Surgery

Gebze Yuzyil Hospital

Gebze, Kocaeli, Turkey

E-mail: dr.sinankilic@yahoo.com

Received: 21-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. AACNT-22-81646; Editor assigned: 25-Oct-2022, PreQC No. AACNT-22-81646(PQ); Reviewed: 08-Nov-2022, QC No. AACNT-22-81646; Revised: 10-Nov-2022, QC No. AACNT-22-81646(R); Published: 17-Nov-2022, DOI:10.35841/aacnt-6.6.126

Citation: Kilic S. Drug induced acute nephritis mimicking acute abdomen: Biopsy-proven a case report. J Clin Nephrol Ther. 2022;6(6):126

Abstract

Background: Acute interstitial nephritis is among the causes of abdominal pain. We aimed to demonstrate acute interstitial nephritis, which can occur after intentional drug use as a suicide attempt and can be confused with acute abdomen.

Case presentation: A 15-year-old girl described tenderness in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen in the examination and free fluid was existent in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen according to the abdominal ultrasound results. She was referred to a nephrology department because her creatinine value was 3.4 mg/dl. Although the patient was asked about any drug use, she stated that she had not taken any medication. However, the patient stated that she had taken 13 tablets of valproic acid and doxycycline after a kidney biopsy. The pathology report of the kidney biopsy was consistent with an acute tubular interstitial nephritis case.

Conclusion: Although it is primarily advised to rule out acute abdomen or surgical diagnoses in a patient with abdominal pain, a meticulous medical history should be taken, considering the possibility of a suicide attempt by drug-use.

Keywords

Acute abdomen, Nephritis, Suicide attempt by drug-use.

Background

Abdominal pain is a complaint that frequently leads to admission to hospitals in both infants and adults. Acute abdomen means abdominal pain that requires surgical treatment. Since acute abdomen may require surgical intervention, the abdominal pain should be evaluated urgently. Thus, every abdominal pain should be taken into account by medical practitioners in terms of whether there is a surgical emergency or not. Although the common reasons for abdominal pain are well-known diseases such as acute gastroenteritis, constipation, systemic respiratory viral illness and mesenteric lymphadenitis; sometimes the reason is an acute abdomen that will require surgical intervention. The drugs taken by the teenage patient and the possibility of adverse drug reactions should be taken into consideration.

Acute Interstitial Nephritis (AIN) is also among the lesserknown causes of abdominal pain. It is an immune-mediated type of tubulointerstitial kidney damage that can occur as the result of a secondary or a reactive process; especially as a result of drugs, autoimmune diseases, infections and some hematological disorders [1,2]. Tubulointerstitial inflammation was first described by Biermer [3] and was defined as the distinct entity of acute interstitial nephritis by Councilman [4,5]. On the other hand, Drug-Induced Acute Interstitial Nephritis (DI-AIN) was first reported in 19466. In this pathological condition caused by sulfonamides, several clinical symptoms, including allergic reactions, were observed in the patient6. Acute interstitial nephritis is characterized by eosinophilic inflammatory infiltration in the renal interstitium and is associated with acute failure in glomerular function. Medications are by far the most frequent cause of acute interstitial nephritis. This etiology makes up approximately 70% (perhaps as high as 90%) of the cases [6]. Theoretically, almost any drug might cause AIN. While more than 250 drugs for miscellaneous types of treatment were reported as the cause of AIN, multiple drug use was to blame in 15% of the cases. Drugs cause a low but significant dose-independent risk of starting a hypersensitivity reaction that can cause acute interstitial nephritis. Other causes include autoimmune diseases, infections, sarcoidosis and uveitis. The most common cause of AIN is a medication that is responsible for almost 65% of AIN cases and antibiotics are the leading cause among almost all drug classes. The gold standard in the diagnosis of AIN is a kidney biopsy, which reveals classical pathologic signs of inflammatory infiltration in renal the interstitium.

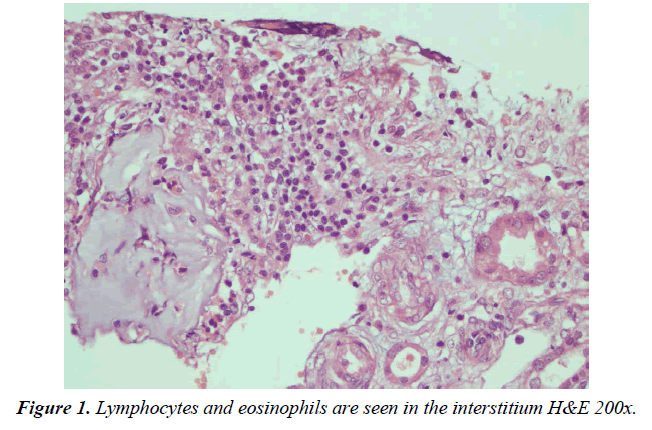

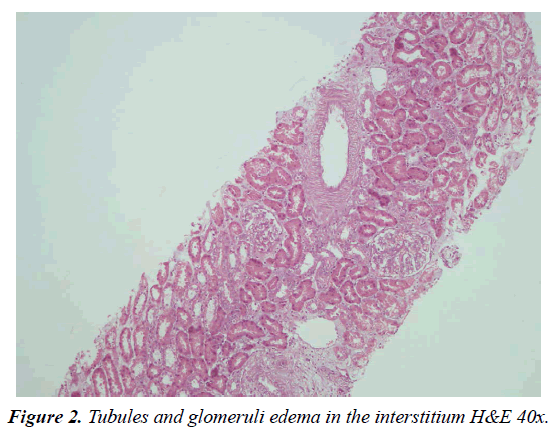

Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis is a well-known reason for acute renal injury and usually manifests as an unexplained increase in blood creatinine levels. A renal biopsy is urgently needed to make a definitive diagnosis and start treatment. The distinctive pathologic signs of DIAIN oedema and inflammation in the interstitium, tubulitis with a dominance of T lymphocytes (CD4+) and mononuclear cells with varying numbers of eosinophils.

A meticulous anamnesis taking and performing a thorough physical examination is crucial to determine the origin of acute abdominal pain and it’s important to terms of identifying the other rare conditions; because an excessive number of different underlying causes may make it difficult to diagnose.

Case presentation

A 15-year-old girl was admitted to the emergency service of the hospital with abdominal pain that had been ongoing for three days. She did not complain of symptoms, such as fever, nausea, vomiting or diarrhea other than abdominal pain. Physical examination revealed a temperature of 37.1°C, pulse rate of 98/min, respiratory rate of 23/min and blood pressure of 104/62mm Hg. Heart and lung examinations were unremarkable. Abdominal examination revealed tenderness in the right lower quadrant, while the bowel sounds were normal. Laboratory tests demonstrated mild leukocytosis (12.88×109/l) and elevated creatinine value (3.2 mg/l). Abdominal ultrasonography was performed because of the tenderness in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. There was free fluid around the caecum according to the ultrasound report and practitioners of paediatric surgery were consulted for the suspected acute appendicitis. While the patient was being monitored for acute abdomen, she was referred to the pediatric nephrology service due to the continued high creatinine value (3.4 mg/dl). The creatinine value of the patient, who was followed up with a preliminary diagnosis of acute renal failure, first increased to 3.9 mg/dl and then to 4, 69. In other laboratory tests such as complement 3-4 (C3-C4), hemogram and the blood pressure artery values were evaluated to be systolically and diastolically (98/65mmHg) normal. In the urinalysis, 3+ proteinuria was detected. The patient was started on Methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) intravenously. She was consulted by ophthalmology because tubulointerstitial nephritis was reported together with autoimmune diseases such as sarcoidosis uveitis. The creatinine values measured on the 3rd day of the patient's hospitalization decreased to 1.65mg/dl. Kidney biopsy was performed on the patient. Although the patient was questioned about the drugs she had used during her hospitalization, she reported to not taking any medication. However, the patient stated that she took 13 tablets (valproic acid and doxycycline) after a kidney biopsy. The kidney ultrasound report and the hematocrit follow-up of the past were also evaluated to be normal after the drug use had been learned. The pathology result of the patient after discharge was compatible with acute tubular interstitial nephritis. According to the micro evaluation of the kidney biopsy, interstitium edema and accumulation of lymphocytes and eosinophils in the interstitium were observed (Figure 1-2).

Discussion

AIN is defined as the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the renal interstitium. This infiltration leads to renal injury. It causes acute renal failure in approximately one in three cases. There are two phases of the clinical course: oliguric and nonoliguric [6,7]. Etiological causes may be allergic, infectious, autoimmune, systemic and idiopathic or drug-induced. the gold standard diagnostic method for AIN is a kidney biopsy and inflammatory infiltration and edema in renal interstitium are the prominent hallmark features in the classical pathology biomarkers. According to experimental models, humoral and cellular reactions have been shown to play an important role in the pathophysiology of AIN. However, in humans, unlike animals, it is clear that the cellular immune mechanism plays the most important role [8]. As soon as the diagnosis of AIN is made, any drug used or suspected to have been used should be discontinued immediately. Oral or preferably intravenous steroid therapy should be quickly started afterward. Steroid therapy is directly proportional to rapid and definite recovery. In some rare cases, full recovery may not be achieved.

Most patients with AIN, regardless of the causes, present symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or signs of acute deterioration in kidney function. In our case, the patient's first symptom was severe abdominal pain. As in our case, patients have severe abdominal pain due to the pressing of the renal capsule caused by an interstitial event. When kidney-related signs and symptoms are evaluated, all patients are observed to have sudden deterioration in kidney function, which is usually non-oliguric. However, about 40% of the patients may develop serious insufficiency that requires dialysis. In our case, oliguria was not observed. Signs of a hypersensitivity reaction such as maculopapular rash, fever and eosinophilia may be observed. Only in 10% of the patients, these three signs are observed together [9]. These clinical findings were not observed in our case. The infiltration is always accompanied by interstitial edema. In the patient who was followed up regarding elevated creatinine levels, it was possible to see AIN pathological findings together with the kidney biopsy performed. In the first stage of treatment, the drug that causes AIN should be stopped. However, when the drug causing kidney damage is stopped, 30-70% of patients do not return to normal renal functions. Although controlled randomized studies are not yet convincing enough, methylprednisolone therapy is still the most effective approach [10,11]. In addition; the use of steroids in the treatment of AIN has been demonstrated in three extensive retrospective studies [12,13].

Conclusions

AIN should be suspected in the presence of elevated creatinine in routine biochemical tests performed on the patient who is followed up regarding the clinical picture of the acute abdomen as in this case. When there is an increase in the intake of medications, especially antibiotics, the increase in the prevalence of AIN is notable. Drug intake history should be questioned more meticulously, especially when following patients in the adolescent age group. The first step in treatment is to determine the etiological factor. The suspected drug should be discontinued in patients suffering from drug-related AIN.

References

- Neilson EG. Pathogenesis and therapy of interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 1989;35(5):1257-70.

- Muriithi AK, Leung N, Valeri AM, et al. Biopsy-proven acute interstitial nephritis, 1993-2011: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(4):558-66.

- Dick GF, Dick GH. The etiology of scarlet fever. J Am Med Assoc. 1924;82(4):301-02.

- Councilman WT. Acute interstitial nephritis. J Exp Med. 1898;3(5):393-420.

- Michel DM, Kelly CJ. Acute interstitial nephritis. J Ame Soc Nephrol. 1998;9(3):506-15.

- Baker RJ, Pusey CD. The changing profile of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(1):8-11.

- Joyce E, Glasner P, Ranganathan S, et al. Tubulointerstitial nephritis: diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(4):577-87.

- Krishnan N, Perazella MA. Drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis: pathology, pathogenesis, and treatment. IJKD. 2015;9(1).

- Praga M, González E. Acute interstitial nephritis. Kidney Int. 2010;77(11):956-61.

- Rossert JA, Fischer EA. Acute interstitial nephritis. In: Floege J, Johnson RJ, Feehally J. Comprehensive clinical nephrology. 5th Ed. Missouri: Elsevier Saunders 2015; 728.

- Fogo AB, Lusco MA, Najafian B, et al. AJKD atlas of renal pathology: acute interstitial nephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67(6):e35-6.

- de Nefritis Intersticiales GM, González E, Praga M. When to use steroid treatment for those patients with drug-induced acute interstitial nephritis? Nefrología (English Edition). 2009;29(2):95-8.

- Clarkson MR, Giblin L, O'Connell FP, et al. Acute interstitial nephritis: clinical features and response to corticosteroid therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(11):2778-83.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross Ref