Review Paper - Biomedical Research (2019) Volume 30, Issue 1

Drainage versus no drainage after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis

Wenjie Huang1, Liying Ying2 and Yuzhu Jia3*

1Department of Urology, the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China

2School of Nursing, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou, China

3Department of Radiology, Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province, Hangzhou, China

- *Corresponding Author:

- Yuzhu Jia

Department of Radiology

Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province, China

Accepted on April 19, 2018

DOI: 10.35841/biomedicalresearch.30-18-120

Visit for more related articles at Biomedical ResearchAbstract

Objective: To conduct a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) meta-analysis to assess the effectiveness of drains in reducing complications after Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy (LC) for acute cholecystitis.

Methods: An electronic search of PubMed, EMBase, Science Citation Index, and the Cochrane Library from January 1990 to January 2016 was performed to identify randomized clinical trials that compare prophylactic drainage with no drainage in LC for acute cholecystitis. The outcomes were calculated as Odds Ratios (ORs) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) using RevMan 5.2.

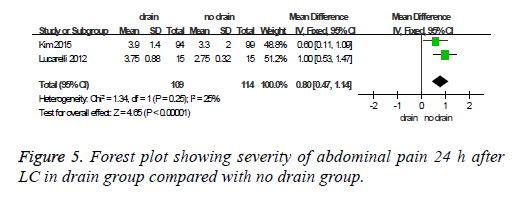

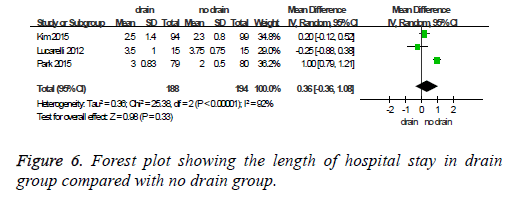

Results: Three RCTs, which included 382 patients, were identified for analysis in our study. There was no statistically significant different in the rate of morbidities (OR=1.23, 95% CI 0.55-2.76, P=0.61). Abdominal pain 24 h after surgery was more severe in the drain group (MD=0.80, 95% CI 0.47-1.14; P<0.00001). No significant difference was present with respect to wound infection rate and hospital stay.

Conclusion: Placement of drain is not beneficial for the prevention or reduction of postoperative morbidities after emergent laparoscopic cholecystectomy and can even increase postoperative pain.

Keywords

Acute cholecystitis, Cholecystectomy, Drain.

Introduction

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy (LC) is widely acknowledged as the definitive management for either elective cholecystectomy or emergent cholecystectomy [1-3]. With the advent of LC, the use of the drainage of the hepatic bed after LC may be justified because of the increased incidence of biliary injury and, consequently, bile leakage. Prophylactic drainage after abdominal surgery has been widely used either to detect early complications, such as postoperative hemorrhage or leakage, or to remove collections such as ascites, blood, and bile. However, evidence-based data do not support the routine use of prophylactic drainage in many abdominal surgery procedures [4-6]. Actually, it is now considered that prophylactic drainage is not necessary after elective LC for chronic cholecystitis [7].

However, prophylactic drainage after LC for acute cholecystitis is still controversial. Many surgeons habitually placed an abdominal drain after emergent cholecystectomy, without any doubt regarding the actual effectiveness of drainage [8]. Nevertheless, some surgeons advocate that drainage of the abdominal cavity has no advantage for detecting bile leakage or bleeding, and it is not helpful for preventing postoperative morbidities. Recently, some studies [9-12] have indicated that routine drainage is not needed to prevent postoperative after surgery for acutely inflamed gallbladder. There is no solid evidence to support routine abdominal drainage after LC for acute cholecystitis. For this reason, we conducted this meta-analysis with the aim to assess the helpfulness of the routine use of drainage in reducing morbidities after emergent LC.

Materials and Methods

Searching strategy

The methods for the analysis and generation of inclusion criteria were conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [13]. An electronic search of PubMed, Embase, the Science Citation Index, and the Cochrane Library from January 1990 to January 2016 was performed to identify all of the related published RCTs comparing prophylactic subhepatic drainage with no drainage in LC for acute cholecystitis. The keywords used in the searches were as follows: acute cholecystitis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, laparoscopy, drain, drainage. The language was restricted to English only. The citations within the reference lists of the articles were searched manually to identify any additional eligible studies.

Study selection

The studies were considered eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT); (ii) Patient undergoing LC for acute cholecystitis; (iii) With reported outcome comparing prophylactic subhepatic drainage with no drainage. Abstracts from conferences and full texts without raw data that was available for retrieval, duplicate publications, letters, non-randomized trials, retrospective analyses and reviews were excluded. The primary outcome, in this meta-analysis, was morbidity rate and intra-abdominal abscess. The secondary outcomes were as follow: wound infection, abdominal pain and length of hospital stay.

Quality assessment

The literature quality was independently assessed by two authors Xiaoli and Huang by utilizing the modified Jadad Scale [14], where 7 points as the maximum possible score. Studies with a score of 4 or more were defined as high-quality studies. Those with a score of 3 or less were defined as low quality.

Data extraction and statistical analysis

Two reviewers Xu and Wenjie independently extracted the relevant information from each article by a standardized form. Information regarding the characteristics of the study population, authors, publication year, study period, country, sample size, interventions and the relevant outcomes were recorded. Disagreements between reviewers regarding data abstraction were resolved by consensus. Statistical analysis of dichotomous variables was performed using the Odds Ratio (OR) as the summary statistic, while continuous variables were analysed using the weighted Mean Difference (MD). For both variables, 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were reported. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. The heterogeneity among the studies was evaluated using the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test, with its significance set at P<0.1 and the extent of inconsistency was assessed with the I2 statistic [15]. I2 values>50% were defined as significant heterogeneity. In cases that lacked significant heterogeneity, fixed-effects models were used for the meta-analysis. If significant heterogeneity is present; the random-effects were applied. For these tests, a P-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were conducted with Review Manager Version RevMan 5.2.

Results

Search results and reporting quality

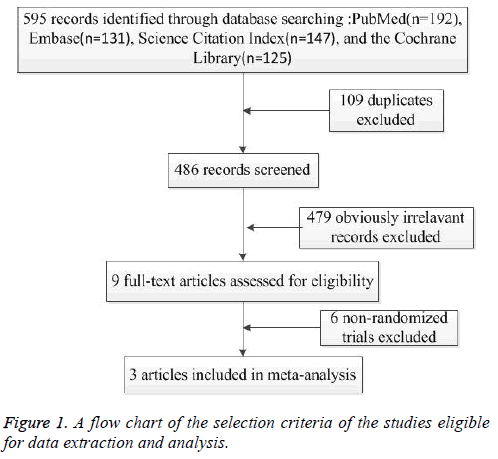

A flow diagram for study inclusion and exclusion is presented in Figure 1. The initial searches generated 585 citations, of which 3 studies [10-12] considered to be suitable for the final meta-analysis using the stated eligibility criteria. A total of 382 patients (188 drained versus 194 non-drain patients in emergency LC). The characteristics, quality assessment, and outcomes for the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

| Author(year) [Ref] | Study design Level of evidence |

Study period | Comparison | Cases | Sex(M/F) | Age(year) | Duration of drain |

Jadad scale score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kim et al.(2015) | RCT (Multicentre) |

2013-2014 | drains no-drain |

94 99 |

50/44 51/48 |

58.1±15.8 56.0±13.6 |

Not report | 5 |

| Park et al.(2015) | RCT (Single centre) |

2008-2012 | drains no-drain |

79 80 |

51/28 46/34 |

59.2±15.1 55.0±16.1 |

within 24 h after surgery or less than 50 ml/day |

5 |

| Lucarelli et al. (2012) | RCT (Single centre) |

2011-2012 | drains no-drain |

15 15 |

6/9 4/11 |

59.0(36–84) 67.5(37–88) |

24 h after surgery | 7 |

Table 1: The characteristics and quality assessment of the included studies.

Meta-analysis results

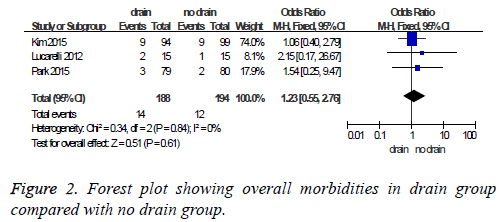

Overall mortality and morbidity: There was no postoperative mortality in all studies. Total patient morbidities were 14/188 (7.45%) in the drain group and 12/194 (6.19%) in the no drain group. Pooled analysis showed no statistically significant difference (OR=1.23, 95% CI 0.55-2.76, P=0.61) (Figure 2). Heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2=0, P=0.84).

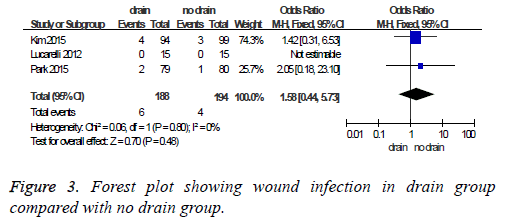

Wound infection: The wound infection rate was 3.19% in the drain group compared to 2.06% in the no drain group. Pooled analysis showed no statistically significant difference (OR=1.58, 95% CI 0.44-5.73, P=0.48) (Figure 3).

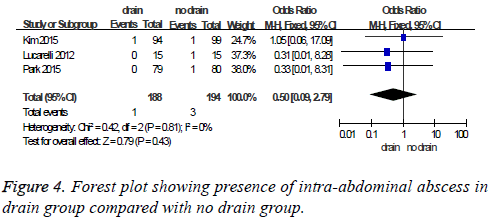

Heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2=0, P=0.80).Intra-abdominal abscess: Intra-abdominal abscess was present in 1 of 188 patients (0.53%) in the drain group and 3 of 194 patients (1.55%) in the no drain group. Pooled analysis showed no statistically significant difference (OR=0.50, 95 % CI 0.09-2.79, P=0.43) (Figure 4). Heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2=0, P=0.81).

Abdominal pain: Two studies [10,11] provided information about the 24 h postoperative abdominal pain. Abdominal pain 24 h after surgery was less severe in the no drain group (MD=0.80, 95% CI 0.47-1.14; P<0.00001) (Figure 5). Heterogeneity was not statistically significant (I2=25%, P=0.25).

The length of hospital stay: There was no difference in the length of hospital stay (MD 0.22 day, 95% CI-0.45 to 0.89). Heterogeneity was statistically significant (I2=92%, P<0.00001) (Figure 6).

Discussion

Because of the severe inflammation and tissue friability in acute cholecystitis, the risk of bile leakage or bleeding after LC could be increased. Therefore, prophylactic abdominal drains have been routinely used in LC for acute inflammatory cholecystitis by many surgeons for the early detection of postoperative bile leakage or any unsuspected hemorrhage and the possibility to evacuate abdominal fluid collections without the need for more invasive procedures. But this is based on traditional teaching and not on clear scientific evidence. The effectiveness of routine drainage after LC for acute cholecystitis remains controversial and debatable [16]. An experimental study [17] showed that when a drain is inserted in the peritoneal cavity that contains no fluids, it is quickly surrounded by omental tissue and completely occluded within 48 h and then loses the function of detection. Moreover, severe bleeding or bile leakage that require additional management can be rapidly diagnosed by a change in clinical symptoms or laboratory results, without the information provided by drainage. In fact, the incidence of serious complications, such as hemorrhage or bile leakage after LC performed for acute cholecystitis, only range from 0.1% to 0.9% [18,19]. Because the rate of these morbidities is relatively rare, it is expected that the clinical significance of routine drainage would be very low. In our study, there was no statistically significant difference between the drain and no drain groups in terms of postoperative morbidity, mortality, and the length of hospital stay.

The wound infection and intra-abdominal abscess rates were similar between the two groups with no significant differences. However, many authors [20,21] reported that the drain may become a bacterial entrance into peritoneal cavity, which could cause ascending infection and result in wound infection at the insertion site of the drain. Reducing the surgically placed drains is a valid method to decrease wound infection rates.

When postoperative abdominal pain was estimated using the visual analog scale, a higher pain score with significant difference was observed in the drain group than no drain group 24 h after surgery. The increase in pain by drain insertion is probably because of the irritation of the peritoneum and the skin at the entry point of the drains by a foreign material.

This meta-analysis has some limitations that should be acknowledged when considering the results. First, the number of RCTs included in this study was only three, which is considered lower quality. Second, the available data from the included studies did not enable us to perform a reliable metaanalysis about the abdominal fluid collection, operative time, shoulder tip pain, postoperative nausea and vomiting. Third, the characteristics of included patients were not consistent among studies leading to some heterogeneity in our overall analyses. In the study of Kim [10], the patients were composed of acute edematous cholecystitis, gallbladder empyema and even gallbladder gangrene. However, patients were excluded if they were gangrenous or emphysematous cholecystitis in the study of Lucarelli [11]. For all considerations of limitation, more high-methodological quality RCTs with an adequate number of patients and homogeneously collected data are warranted.

In summary, this is the first meta-analysis to assess the role of drainage after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. We found no significant advantage of using drainage after LC. Placement of drain is not beneficial for the prevention or reduction of postoperative morbidities after emergent LC and can even increase postoperative pain. Therefore, the drainage in LC performed to treat an acute inflamed gallbladder should be avoided, except in unusual cases when intraoperative complications occur.

References

- Strasberg SM. Clinical practice. Acute calculous cholecystitis. N Engl J Medi 2008; 358: 2804-2811.

- Gurusamy KS, Davidson C, Gluud C. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for people with acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Datab Sys Rev 2013; 6: 005440.

- Koti RS, Davidson CJ, Davidson BR. Surgical management of acute cholecystitis. Langenbecks Arch Surg/Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Chirurgie 2015; 400: 403-419.

- Launay-Savary MV, Slim K. Evidence-based analysis of prophylactic abdominal drainage. Annales de Chirurgie 2006; 131: 302-305.

- Karliczek A, Jesus EC, Matos D. Drainage or nondrainage in elective colorectal anastomosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorect Dis J Assoc Coloproctol Great Britain Ireland 2006; 8: 259-265.

- Petrowsky H, Demartines N, Rousson V. Evidence-based value of prophylactic drainage in gastrointestinal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 1074-1084; discussion 84-85.

- Gurusamy KS, Koti R, Davidson BR. Routine abdominal drainage versus no abdominal drainage for uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Datab Sys Rev 2013; 9: 006004.

- Navez B, Ungureanu F, Michiels M. Surgical management of acute cholecystitis: results of a 2-year prospective multicenter survey in Belgium. Surg Endosc 2012; 26: 2436-2445.

- Bawahab MA, Abd El Maksoud WM, Alsareii SA. Drainage vs. non-drainage after cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a retrospective study. J Biomed Res 2014; 28: 240-245.

- Kim EY, Lee SH, Lee JS. Is routine drain insertion after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis beneficial? A multicenter, prospective randomized controlled trial. J Hepato Biliary Pancreatic Sci 2015; 22: 551-557.

- Lucarelli P, Picchio M, Martellucci J. Drain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis. a pilot randomized study. Ind J Surg 2015; 77: 288-292.

- Park JS, Kim JH, Kim JK. The role of abdominal drainage to prevent of intra-abdominal complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: prospective randomized trial. Surg Endoscopy 2015; 29: 453-457.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62: 1006-1012.

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996; 17: 1-12.

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002; 21: 1539-1558.

- Gurusamy KS, Samraj K. Routine abdominal drainage for uncomplicated open cholecystectomy. Cochrane Datab Sys Rev 2007; 2: 006003.

- Agrama HM, Blackwood JM, Brown CS. Functional longevity of intraperioneal drains: an experimental evaluation. Am J Surg 1976; 132: 418-421.

- Kim EY, You YK, Kim DG. Is a drain necessary routinely after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for an acutely inflamed gallbladder? A retrospective analysis of 457 cases. J Gastrointest Surg Off J Aliment Tract 2014; 18: 941-946.

- Schuld J, Glanemann M. Acute cholecystitis. Viszeralmedizin 2015; 31: 163-165.

- Ammori BJ, Davides D, Vezakis A. Day-case laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective evaluation of a 6-year experience. J Hepato Biliary Pancreatic Surg 2003; 10: 303-308.

- Yeh CY, Changchien CR, Wang JY. Pelvic drainage and other risk factors for leakage after elective anterior resection in rectal cancer patients: a prospective study of 978 patients. Ann Surg 2005; 241: 9-13.