Research Article - Research and Reports on Genetics (2018) Volume 2, Issue 2

Distribution of qualitative traits within and between two populations of Nigerian local chickens ecotypes.

Gwaza DS*, Dim NI, Momoh OM

Department of Animal Breeding and Physiology, University of Agriculture, Makurdi, Nigeria

- *Corresponding Author:

- Gwaza DS

Department of Animal Breeding and Physiology

University of Agriculture

Nigeria

Tel: +23408036808979

E-mail: gwazadeeve@yahoo.com

Accepted Date: April 23, 2018

Citation: Gwaza DS, Dim NI, Momoh OM. Distribution of qualitative traits within and between two populations of Nigerian local chickens ecotypes. J Res Rep Genet. 2018;2(2):6-14

Abstract

The study was conducted at Akpehe poultry farm, Makurdi. Nigeria. 1700 local chickens belonging to the Tiv and Fulani ecotypes were used for the study. The study was designed to provide information on the distribution of qualitative traits within and between the ecotypes. The distribution of each qualitative traits was measured on the parent populations as well as on their generations. These were computed as the ratio of their frequencies to the total number of birds. Qualitative traits varied within and between the ecotypes. There were indications of qualitative traits modification for adaptation to climatic challenges. Solid black and black colored related plumages and body pigmentations colors were abundant among the Tiv ecotypes. Color patterns with the capacity to repel radiant heat had higher frequencies in the Fulani ecotypes. There were high distribution of single comb type within and between the ecotypes. Solid black and other black-related plumages and body pigments birds can survive among the Tiv ecotypes populations but not within the fulani ecotypes populations. While the Fulani ecotype can survive within the Tiv ecotypes populations

Keywords

Distribution, Ecotypes, Local-chicken, Qualitative-traits.

Introduction

The Nigeria local chicken had been described as hardy and small bodied. They come in various shapes, sizes and plumage colorations [1,2]. Nwosu [3] reported that the commonest plumage colour patterns are black, red, brown with various laced colours and mottling. The rare colour patterns were light orange, yellow, grey, and white also laced and mottled found within other colours. Nwosu et al. [4] also observed that the Nigerian chickens were characterized by black beak colour, red comb and grey shanks.

A substantial amount of qualitative phenotypic diversity for various traits in the indigenous chicken ecotypes of African Sahara is expected because of diverse agro-climates, ethnic groups, socioeconomic, religions and cultural activities [5]. In addition, natural or man-made catastrophe may accelerate the forces that reduces or modifies allelic frequency, persistency or elimination of certain genes and genotypes from the population’s gene pools [6]. Indigenous domestic chicken in many developing countries may possess similar appearance in some characteristics. However, great variability in morphological characteristics within local population exist [7].

Nthimo [6] reported that local chickens have colourful plumage that may be grouped into two classes, sole colours and mixed colours. Payne [8] observed that the indigenous chicken in the tropics possess light covering of weary feathers that are free from down.

Mukherjee [9] reported that although both melanin and carotenoid pigments contribute to feather color of certain avian species, it is the melanin’s that determine plumage color and patterns. The presence and distribution of the melanin’s result in differences in the feather forms within age and sex, as well as structural variations between and within other feather traits. Oluyemi and Robberts [10] reported that plumage colors have been grouped under four categories: solid, diluted, extension and restriction, and patterns. These authors noted that solid colors include black dominant and recessive white, albinism, depigmentation silver and gold. They stressed that these colors are not pale and do not give the appearance of the diluting effect of genes. By contrast the authors also noted that, diluted colors, though uniform, appear pale suggestive of weakened action of genes responsible for their expression. Color extension and restriction are, though color is present, it is not uniformly distributed to all parts. The authors also noted that instead of causing the distribution of color throughout the entire plumage or among region, color distribution may occur within feathers resulting in patterns. Roberts [11] also reported that each plumage color or pattern is the result of a series of genetically determined events.

Many qualitative traits are ecotypes characteristics. The distribution of qualitative traits between and within local chicken populations could be used to assess the levels of variation, reveals the effects of climate and adaptation to their environment and genetic dissimilarity between and within ecotypes populations. Oluyemi and Roberts [10] reported that comb and wattles on and below the head respectively are a modification of the skin peculiar to the avian class. They added that the comb and wattles play an important role in sensible heat loss. The authors added that the male chicken has more prominent comb and wattles than the females. Obiaha and Oluyemi [11,12] reported that the indigenous tropical chickens and the Mediterranean breeds have more elaborate combs and wattle relative to their body size in contrast to the temperate exotic chickens and that the comb and wattle serve as thermo regulator. Van-kampen [13] reported that this thermoregulatory role would be vital in warm wet climate like South- Western Nigeria. Large combs would therefore be important to ensure the survival and productivity of chicken in such climates. The size of the comb has also been shown to affect the frequency of agonistic behaviors in birds [14]. Mancha and Schwannyana et al. [15,16] reported that red comb color is the commonest among indigenous chicken ecotypes. The objectives of this study were to provides information on the distribution and frequencies of qualitative traits as an insight to assess the levels of adaptation and dissimilarity of the local chickens to their environment.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at akpehe poultry farm, Makurdi. Nigeria. About 1700 local chicken ecotypes comprising of 900 Fulani and 800 Tiv chicken ecotypes were used for the study. The birds were raised on dip litter in half walls wire-netting houses. Routine medication and sanitation were provided. The birds were fed formulated concentrate feed adlibitum. The distribution of qualitative traits were measured on the parent stock as well as on their progenies. The abundance of each qualitative traits was measured as a ratio of their frequencies to the total number of birds.

Correlation among qualitative traits and performance traits of indigenous chicken ecotypes

Body length had been reported to be related to plumage colour [17]. Pink and blackish-red plumage birds had the longest bodies. This showed that body length could conveniently be selected for using plumage color. Body circumference and shank length have also been reported to be related to plumage color. Chest circumference had been reported to relate with comb and earlobe colors. Thigh length is also related to plumage and comb types [15]. Thus plumage, comb and earlobe colors and comb types could be selected for in order to improve chest circumference and thigh length. Skin color and comb color were also correlated to egg number [15]. Yellow skinned hens laid more eggs than the white skinned; the red combed hens laid wider eggs. Thus selection for larger clutch size and wider egg could be achieved using skin and comb color variations respectively.

Distribution of qualitative traits

The distribution of each qualitative trait was measured on the parent stock as a ratio of its frequency to the total number of birds. This was expressed in percentage.

Results

Description of plumage colors within and between the ecotypes

There were variations in the distribution of plumage color within the Tiv ecotype. The common plumage colors were blackishbrown (23.08%), mottled brown (19.20%), solid brown and solid black 11.54% each respectively were more common than silver brown (6.25%), mixed grey and white mottled (3.85 and 3.85%) respectively (Table 1), Figures 1-6. Mottled plumage color pattern were more common (36.54%) than all the other plumage color variants (Table 2). The solid plumage colors were significantly (P>0.05) more among the hens than in cocks. Mottled plumage colors dominated in both sexes among the Tiv ecotypes. Within the Fulani ecotype, plumage colors also varied. The commonest plumage colors were black brown (17.37%), solid brown (17.31%) and mixed black (13.46%) (Table 2). Mottle brown (13.46%) mottled white (9.62%) and mottled black (11.53%) were more numerous than mixed grey (5.77%) and light brown (5.77%) (Table 1) solid white (3.08%) and dull brown (2.69%) were fewer (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 7-9). Again mottled plumage color variants were significantly (P<0.05) more (34.62%) than the other plumage color variants (Table 2). The solid plumage colors were more common among the hens than in cocks. Mottle plumage colors occurred in both sexes within the Fulani ecotype.

Table 1. Diversity in plumage colour distribution of the Tiv local chicken ecotypes.

| Plumage Colour | Number of Birds | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Silver brown | 15 | 6.25 |

| Mottled | 50 | 19.20 |

| Mottle black | 30 | 11.54 |

| Black brown | 60 | 23.08 |

| Solid brown | 30 | 11.54 |

| Solid black | 30 | 03.85 |

| Mixed grey | 10 | 03.85 |

| Light brown | 20 | 07.69 |

| White mottle | 10 | 03.85 |

| Total | 260 | 100.00 |

Table 2. Disctribution of distinct principal background and non distinct principal background plumage colours in the Fulani and Tiv local chicken ecotypes.

| Plumage Colour Variant | Ecotype | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fulani | Tiv | All | ||||

| n | % total | n | % of total | n | % of total | |

| Distinct plumage colour | 75 | 28.85 | 98 | 37.69 | 173 | 33.27 |

| No district plumage colour | 185 | 71.15 | 162 | 62.31 | 347 | 66.73 |

| Moltled plumage colour | 90 | 34.62 | 95 | 36.54 | 185 | 35.58 |

| Solid black colour | 15 | 5.77 | 30 | 11.54 | 45 | 8.65 |

| Solid white colour | 8 | 3.08 | - | - | 08 | 1.54 |

| Solid brown colour | 45 | 17.31 | 30 | 11.54 | 75 | 14.42 |

n=number of observations.

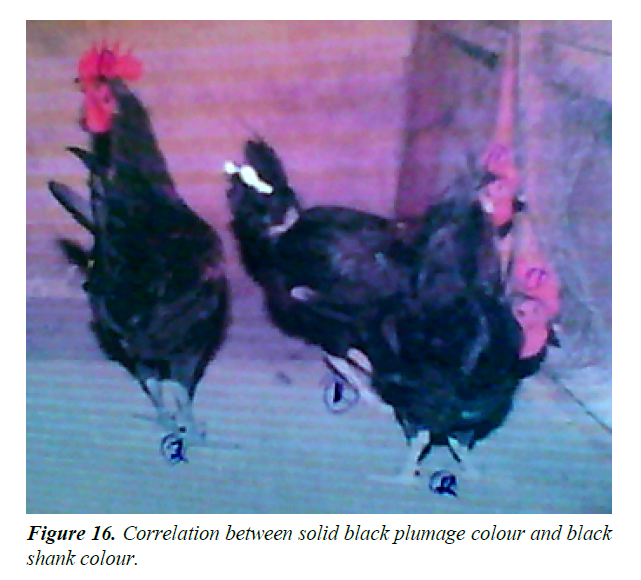

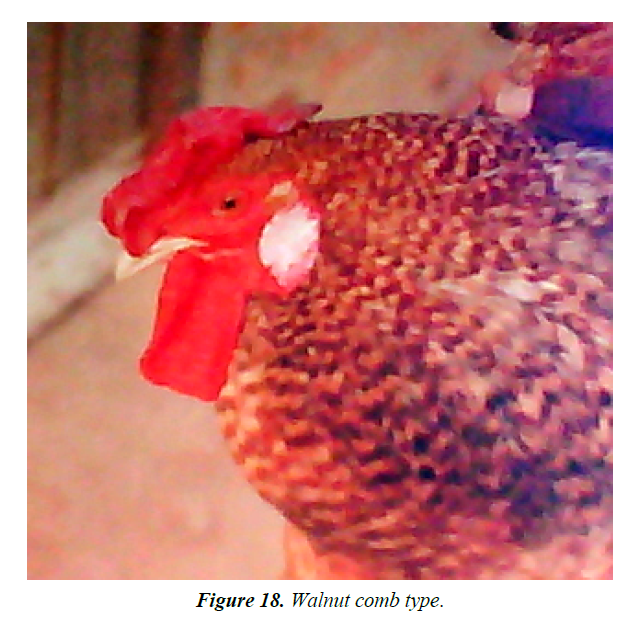

The distribution of plumage colors between the ecotypes also varied. Out of the 520 birds examined in the study, those with distinctly principal background plumage colors of silver, solid brown, solid white and solid black were 173 (33.27%) (Table 2; Figures 10-18). Those with no distinctly principal back ground plumage colors were 347 (66.73%) (Table 2; Figures 5, 11, 12, 15 and 19). Distinct principal background plumage colors were significantly (P<0.05) higher in the Tiv ecotype 98 (37.69%) than 75 (28.85%) in the Fulani ecotype (Table 2). Plumage colors without distinct principal background were significantly (P>0.05) higher in the Fulani ecotype 185 (71.15%) (Table 2; Figures 5, 10, 11 and 12) than 162 (62.31%) (Table 2; Figures 20 and 21) in the Tiv ecotype (Table 2). Mottled plumage colour pattern were high in both the Tiv 95 (36.54%) and the Fulani 90 (34.62%) ecotypes (Table 2). Solid black plumage colour was significantly (P<0.05) higher in the Tiv ecotype 30 (11.54%) (Tables 1 and 2; Figures 16 and 18) than 15 (5.77%) in the Fulani ecotype (Table 2). Solid brown 45 (17.31%) and solid white 8(3.08%) were more common in the Fulani ecotype than 30 (11.54%) and 0 (0.00%) respectively in the Tiv ecotype (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 3. Distribution of qualitative traits in the Tiv and Fulani local chicken population.

| Traits | Phenotype | Ecotypes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiv | Fulani | All | |||||

| n | % of total | n | % of total | n | % of total | ||

| Beak Colour | White | 54 | 20.77 | 51 | 19.60 | 105 | 20.19 |

| Black | 91 | 35.00 | 95 | 36.50 | 186 | 35.77 | |

| Brown | 115 | 44.23 | 114 | 43.90 | 229 | 40.04 | |

| Skin Colour | White | 260 | 100.00 | 260 | 100.0 | 520 | 100.0 |

| Comb Colour | Red | 260 | 100.00 | 260 | 100.0 | 520 | 100.0 |

| Shank Colour | White | 94 | 36.15 | 182 | 70.0 | 276 | 53.08 |

| Green | 33 | 12.69 | abs | abs | 33 | 6.35 | |

| Black | 133 | 51.15 | 78 | 30.0 | 211 | 42.5 | |

| Eye Colour | Yellow | 132 | 50.77 | 200 | 76.9 | 332 | 63.85 |

| White | 52 | 20 | abs | abs | 52 | 10.0 | |

| Brown | 76 | 29.23 | 60 | 23.1 | 136 | 26.15 | |

| Earlobe Colour | Black | 79 | 30.38 | 58 | 22.3 | 137 | 26.35 |

| White | 30 | 11.54 | 117 | 45.0 | 147 | 28.27 | |

| Brown | 103 | 39.62 | 85 | 32.7 | 188 | 36.15 | |

| Red | 48 | 18.45 | abs | abs | 48 | 9.23 | |

| Comb Types | Single | 259 | 99.62 | 258 | 99.23 | 517 | 99.42 |

| Walnut | 01 | 0.38 | 01 | 0.39 | 02 | 0.39 | |

| Rose | abs | abs | 01 | 0.19 | 01 | 0.19 | |

n=number of observation; Abs=absent.

Description of beak colors within and between the ecotypes

Three beak colors were observed (brown beak, black beak and white beak) in the Tiv ecotype (Tables 2 and 3). Brown beak color was significantly highest (P<0.05) 115 (44.23%), followed by black beak color 91 (35.00%) White beak color was least 54 (20.74%) (Table 3). Among the Fulani ecotype the brown beak was most common 114 (43.90%) followed by the black beak 95 (36.50%) (Table 3). The white beak color was also least 51 (19.60%) (Table 3). In all the ecotypes, Brown beak color were most common 229 (40.04%) followed by black beak color 186 (35.77%), while white beak color 105 (20.19%) was least (Table 3).

Description of skin colors within and between the ecotypes

One skin color (white color) was observed within and between the ecotypes (Tables 2 and 3). White skin had 100% occurrence in both the Tiv and the Fulani ecotypes. There were also no sex differences in relation to skin colour.

Description of shank coolers within and between the ecotypes

Three shank colors were observed (white, green and black) in the Tiv ecotype (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 14-16). The black shank color was most common 133 (51.15%) followed by the white shank 94 (36.15%). Green shank had 33 (12.69%) occurrence among the Tiv ecotype (Tables 2 and 3). In the Fulani ecotype, two shank colors were observed (white and black). The white shank color had 182 (70.00%) occurrence against the black shank color 78 (30.00%) (Tables 2 and 3). Between the ecotypes green shank color occurred only among the Tiv ecotype, while the white shank colour is most common in the white Fulani ecotype (Tables 2 and 3).

Description of comb colors within and between the ecotypes

One comb color (red) was observed between and within the ecotypes (Tables 1-3; Figure 4). Red comb color had 100% occurrence in both ecotypes. There was also no sex difference in relation to comb color of the birds.

Description of eye colors within and between the ecotypes

Three eye colors were observed (yellow, white and brown) among the birds of the Tiv ecotypes (Tables 2 and 3). Yellow eye color was most common 132 (50.77%). This was followed by the brown eye colored birds 76 (29.23%). The white eye colored birds were least 52 (20.00%) (Tables 2 and 3). Among the Fulani ecotypes, two eye colors (yellow and brown) were observed (Tables 2 and 3). The yellow colored birds were most common 200 (76.90%). There were least number of brown eye colored birds 60 (23.10) (Tables 2 and 3).

Description of ear lobe colors within and between the ecotypes

Four earlobe colors (white, black, brown and red) were observed among the Tiv ecotype (Tables 2 and 3). Brown earlobe colored birds were most 103 (30.38%). This was followed by the black earlobe colored birds 79 (30.38%). Red and white earlobe colored birds were 48 (18.46%) and 30 (11.54%) respectively (Tables 2 and 3). Among the Fulani ecotype, three earlobe colors (Black, white and brown) were observed (Tables 2 and 3). White earlobe colored birds were most predominant 117 (45.00%). This was followed by the brown earlobe colored birds 85 (32.70%). Black earlobe colored birds had 58 (22.30%) occurrence (Tables 2 and 3).

Correlation between plumage color and shank color

There was correlation between solid black mixed grey, mottled black, blackish-brown and mottled brown plumage colors with black shank color. Light brown and white mottled plumage colors correlated with white shank color (Figures 14-18).

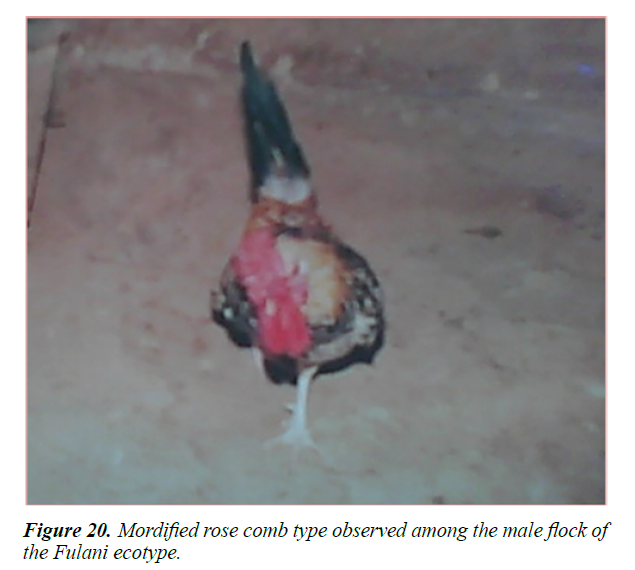

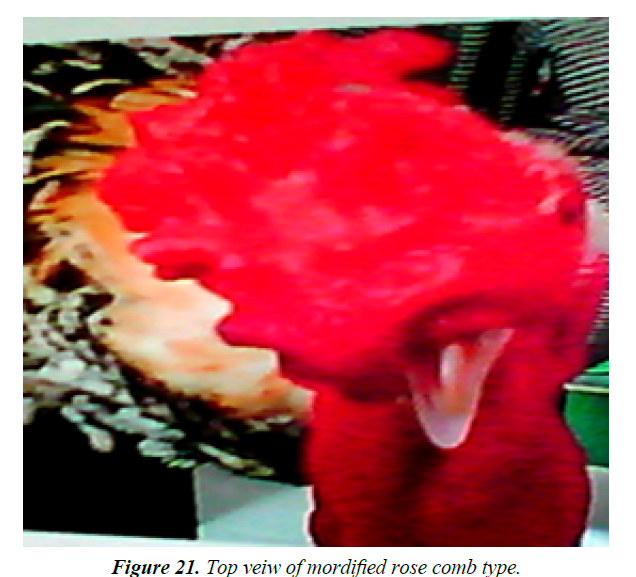

Description of comb types within and between the ecotypes

Two comb types (single and walnut) were observed among the Tiv ecotype (Tables 3 and 4; Figures 18-20). Single comb type was most common 259 (99.61%); while walnut comb type accounted for 01 (0.39%) (Table 3). In the Fulani ecotype three comb types (single, walnut and rose) were observed (Tables 2 and 3; Figures 19-21). Again the single comb type birds were predominant 258 (99.23%) while walnut and rose comb types record 01(0.39%) each respectively (Tables 2 and 3).

Discussion

Description of birds by plumage color

The highly variable shades of plumage color observed in the study [17-19]. The multicolor variation is most likely an adaptation feature for survival [20], or lack of conscious selection and breeding programmes directed towards choice of colour [4]. Social preference, unconscious selection in addition to natural selection and adaptation could be major causes of the variation in plumage color [21]. The wide plumage color variant may also be due to culture and religion that arises from the ethnic and religious differences of their keepers. Plumage colour in birds had been reported to be controlled by the E locus which enhances the distribution of melanin [9]. Other genes also modified, restricts [22], eumelanization. Accumulation of eumelanin intensifiers could also be responsible for solid black color variants [23]. A number of genes acts as eumelanin inhibitors and modify plumage colors. Mixed plumage colors and pattern resulted from interactions between genes at a number of difference loci in addition to the activities of unidentified modifying genes that behave like a polygenic complex and tissue specific mutations [24]. The abundance of single pure brown colour (11.54%), in the Tiv ecotype compare favorably with the findings of Saidu [25], while 11.54% and 23.08% were higher than that observed by Mancha [15]. The abundance of the solid black and black brown in the Tiv ecotype may be due to interactive effect of the birds with the environment by seeking shelter under shrubs, bushes, tree crops, and hut shades, an avenue not available to the Fulani ecotype.

Description of birds by body pigmentation

The proportions of brown beak (44.23%), black beak (35.00%), and white beak (20.74%) observed in this study agreed with the reports of Mancha [15] who reported 43.09 and 30.7 percent for brown and black beak in chickens of Plateau Southern zone. Beak colour is due to pigmentation [26]. The observed beak pigmentation in birds studied has been affected by social preference, natural selection, adaptation and nutrition [21]. One skin colour (white) observed did not agree with the report of Saidu [25] who reported several skin colours. This may be due to the genotype of the birds that metabolized carotene in the diet precluding it to be stored under the skin.

The three shank colours (black, white and green) observed in this study [16,27]. Shanks are covered with scales. The black shank colour was due to presence of melanin in the dermis, while the green shank colour was due to presence of melanin pigment in the epidermis, while the white shank colour was due to the absence of both the lipochrome and melanin pigment. Again the multiple shank colours in the ecotype has been affected by social preference and natural selection. Since black colour predisposes animals to high heat loads, metabolic rates and increased thyroid activity which together reduced survival rate. The higher black shank colour (51.15%) in the Tiv ecotype than the Fulani (30.00%) was possible due to ecotype by environmental interaction effect by seeking shades under bushes, shrubs, tree crops and hut shades, an environment the Fulani ecotype does not have; hence the highest preponderance of the white shank (70.00%) in the Fulani ecotype.

The red comb colour observed had been reported by Schwannyana et al. [16]. The comb colour was due to the blood of the bird that was visible because the skin of the comb has a rich blood supply that is not masked. These skin areas are so highly vascularized that squeezing a comb between the thumb and the forefinger will more than squeeze out some of the bird blood onto your fingers. The three eye colours (yellow, white and brown) observed in these study [17,25]. Eye colour is a result of pigmentation of a number of structures within the eye (Iris, retina, uveal tract, Giliary).

Four earlobe colours (White, black, brown and red) observed in this study did not all agree with the report of Schwannyana et al. [16] who reported red, white and others that were not prominent or distinctly coloured. The red earlobe colour is due to the blood of the bird that was visible because the skin of the earlobes has a rich supply of blood that is not masked. The white earlobe was due to the purine pigment which is controlled by a number of genes. The black and brown earlobe colors were due to the greenish or yellowish tinge of the white earlobes.

Description of birds by comb types

The three comb types (single, walnut and rose) observed in this study had also been reported [21]. The single comb was most common (99.61%) within and between the ecotypes [12,27]. The highest frequency of the single comb type even in the population of Rr+ was because the RR males have poor fertility in several breeds [28]. Their mating frequency is lower and duration of fertility after single insemination is shorter for RR males. The motility of their sperms after storage is inferior and some enzymatic activities differ [28]. Single comb alleles are epistatic to the comb less type of the Breda [29-31] hence the preponderance of the single comb type between and within the ecotype.

Combs are important avenues for heat loss in birds. Large combs would therefore, be important in ensuring the survival and production of the breed. Natural selection and social preferences have combined effects that stabilized and adapted the single comb type to the environment. The walnut and rose comb types were least common because they tend to reduce heat loss, such that birds with such comb type were predisposed to higher heat load, increased metabolic rate and thyroid activity that led to decreased productivity and increased mortality; hence their low frequency in the population.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Conclusion

Qualitative traits varied within and between the ecotypes populations. There were also indications of plumage colour modifications for adaptation to challenging climatic conditions. Solid black plumage and body pigmentations of black colorations were abundance among the Tiv ecotype as compared to the Fulani ecotype. There were high distribution of single comb type compared to the rose, pea and the wattle as an adaptation to body heat regulation.

Recommendation

Solid black, grey, black colour restriction plumage colours of chickens that has the capacity to absorb heat can survive among the Tiv ecotype populations due to available shades. Plumage colours with the capacity to repel heat were the most common among the Fulani ecotypes. There were correlation between black, grey, light black plumage colours with the black shank. Light plumage colours can be selected for among the fulani ecotype while solid black and black related plumage colors can be selected among the Tiv ecotype local chicken populations.

References

- Oluyemi JA, Oyenuga VA. Evaluation of the Nigerian Indigenous fowl. Proceedings of the 1st World Congress on Genetic Applied to livestock production, Madrid, Spain. 1974;321-8.

- Nwosu CC. Characterization of the local chicken of Nigeria and its potential for meat and egg production. In: Poultry production in Nigeria. Proceedings of the 1st National Seminar on poultry production, Zaria pages. 1979;187-201.

- Nwosu CC. Review of indigenous poultry Research. In: Rural Poultry in Africa; Proceeding of an International Workshop held in Ileife, Nigeria. 1990;6.

- Nwosu CC, Gowen FA, Obiaha FC, et al. A biometrical study of the conformation of the native chickens. Nigerian J Anim Prod. 1985;12:141-6.

- Mogosse HH. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of indigenous chicken population in Northwest Ethiopia. Ph.D Thesis, Department of Animal, Wildlife and Grassland Science. University of the free-state, Bloemfontein, South African. 2007.

- Nthimo AM. The phenotypic characterization of native lessotho chickens. M.Sc thesis, Department of Animal, Wildlife and Grassland Sciences. University of the Free State, Bloemfonteein; South Africa. 2004.

- Horst P. Compendium of result of the EEC-research projects No. TS3-CT92-0091. Final workshop at M’bour, Senegal. 1997;14-8.

- Payne WJA. Introduction to Animal Husbandry in the Tropics. 4th Edition. Longman Group Ltd. 1990;684-726.

- Mukherjee TK. Breeding and selection programmes in developing countries. In: Poultry Breeding and Genetics Elsevier, New York, USA. 1990.

- Oluyemi JA, Roberts FC. Poultry production in warm wet climates. Macmillan Press Ltd, London. 1979;198.

- Oluyemi JA, Roberts FA. Poultry Production. Spectrum Books Ltd, Ibadan. 2000.

- Obiaha EC. A guide to poultry production in the tropics. Accna publishers, Enugu. 1992;212.

- Van Kampen M. Physical factors affecting energy expenditure. In: Energy requirement of poultry. British poultry science limited, Edinburgh. 1974;47-59.

- Dawson JS, Siegal HS. Influence of comb removal and testosterone on agonistic behavior in young fowl. Poultry Sci. 1962;41(4):1103-6.

- Mancha YP. Characterization of Local Chickens in Northern part of the Jos Plateau. Ph.D Thesis Animal Production Programme, School of Agriculture, Abubakar Tafawa Belewa University Bauchi. 2004.

- Schwannyana E, Onyait AO, Ogwal J, et al. Characteristics of Rural Chicken Production in Apal and Kumi Districts of Uganda. 2001;5-10.

- Mbap ST, Zakar H. Characterization of local chickens in Yobe State Nigeria. In: The role of agriculture in poverty alleviation. Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the Agricultural Society of Nigeria (ASN). 2000;126-31.

- Orheruata MA, Okpeku M, Imumorin IG. Phenotypic and Body linear characterization in native and some exotic chickens in Edo State. In: Sustaining livestock production under changing economic fortunes. 2004.

- Lesson A, Walsh T. Feathering in commercial poultry I. Feather growth and composition. World’s Poultry Sci J. 2004;60(1):42-51.

- Odubote IK. Influence of qualitative traits on the performance of West African dwarf goat. Nigerian J Anim Prod. 1994;21:25-8.

- Ikeobi CON, Ozoje MO, Adebambo OA, et al. Frequencies of Feet Feathering and Comb type genes in the Nigerian Local Chicken. Pertanika J Trop Sci. 2001;24(2):147-50.

- Moore JW, Smith JR. Melanotic: key to phenotypic enigma in the fowl. J Heredity. 1971; 62(4):215-9.

- Moore JW, Smith JR. Genetic factors associated with plumage colour pattern on the bared fayoumi. Poultry Sci. 1972; 51(4):1149-56.

- Coles EH. In veterinary clinical pathology, second edition. W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia. 1976.

- Saidu IA. Characterization of local chicken in Bauchi: PGD Dissertation, Animal Production Programme, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University, Bauchi. 2002.

- Lucas AM, Stettenheim PR. Avian Anatomy, Integument. Part H. Agricultural Handbook 362. U.S. Government Printing Office. Washington. D.C. 1972.

- Smith AJ. Poultry. Ed. Revised edition. Mac millan Education Limited. 2001;1-63.

- Crawford RD. Origin and History of poultry species. In: Poultry Breeding and Genetic Elservier, New York; Tokyo. 1990;1123.

- Hutt FB. Genetics of the fowl. McGraw-Hill Book Company Inc., New York. 1949.

- Crawford RD. Domestic fowl. In: Evolution of domesticated animals. Longman Inc. New York. 1984.

- Morejohn GV. Plumage colour allelism in the red jungle fowl (Gallus gallus) and related domestic forms. Genet. 1965;38:519-30.