Research Article - Journal of Mental Health and Aging (2022) Volume 6, Issue 2

Direct and indirect effects of built and natural environment on elderly mental health: A meta-synthesis

Mahdi Khakzand1*, Zohreh Rakhshani2

1Department of Landscape Architecture, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran

2Department of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture and Urban Design, Isfahan Art University, Isfahan, Iran

- *Corresponding Author:

- Mahdi Khakzand

Department of Landscape Architecture

Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran

E-mail: mkhakzand@iust.ac.ir

Received: 27-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. AAJMHA-22- 39628; Editor assigned: 23-Aug-2022, PreQC No. AAJMHA-22- 39628 (PQ); Reviewed: 30-Oct-2022, QC No. AAJMHA-22- 39628; Revised: 16-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. AAJMHA-22- 39628 (R); Published: 18-Mar-2022, DOI:10.35841/AAJMHA-6.2.106

Abstract

The places where people live affect their physical, social, and mental health. This is also true for the elderly. In this review, with the aim of increasing the understanding of how the built and natural environment impact elderly mental health, two scales of environment have been investigated, architecture (personal home and nursing home) and urban. Data were collected from three scientific databases (Science Direct, Scopus, and PubMed). The analysis of the meta-synthesis results demonstrates variety concepts that have direct and indirect effect. The extracted concepts were examined in three categories. By averaging determined that concepts related to Personal homes have a direct impact on mental health with 17.5%, whereas in nursing homes have indirect impact on mental health through physical health with 12.5% and in urban spaces have indirect impact through social health with 18%. Also, the connection with nature in all three spaces simultaneously created both types of effects. In the comparison among all the concepts in three categories, it was found that social interactions with 32% have the greatest impact on mental health

Keywords

Mental health, Elderly, Built environment, Natural environment, direct and indirect effect.

Introduction

In 1946, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared mental well-being as one of three fundamental components of health, along with physical and social well-being. More recently, in 2013, the WHO released its Mental Health Action Plan, which established mental health research as one of its goals [1]. Additionally, in 2015, the United Nations recognized the promotion of mental health and well-being as a health priority of the global development agenda effort [2]. In 2016, 44.7 million adults in the United States (US) lived with a mental illness [3]. Internationally, the WHO reported that in 2016, neuropsychiatric disorders were the third leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in Europe, behind only cardiovascular diseases and cancer. In 2017, the WHO reported that depression was the leading cause of disability worldwide. Specifically, depression was identified as the single largest contributor to nonfatal health loss globally [4]. In addition the whole world is aging; both the number and proportion of older people is increasing in post-industrial and developing nations. It is projected that by 2050, 21% of people will be more than 60 years old [5].

With the increasing global population of older adults, there is a need to consider built and natural environmental factors that directly and indirectly (through physical and social health) affect the mental health and emotional well-being of the elderly. Many studies have been carried out on the elderly and their mental, physical, and social needs, which in some cases have led to improved care for the elderly in private centres, but research conducted in the last decade shows that the cause of many elderly mental health problems is environment-related [6-8]. The purpose of this article is to synthesize peer research in a literature review, to understand how the environment (direct or indirect) affects the mental health of the elderly.

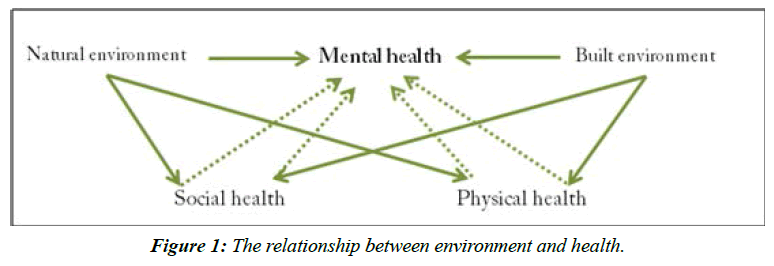

One of the today’s challenges in built and natural environment is supporting mental health for older users. The aging process brings about changes in elderly person´s physiological and psychological capacities, as well as predisposing them to depression, [9,10] that One of the important causes of depression is a decrease in the daily activities of the elderly. Thus, due to their loss of or reduction in autonomy, the built and natural environment gains more significance. Research demonstrates that mental health is closely related to physical and social health [10,11] all of which are influenced by environmental factors (Figure 1).

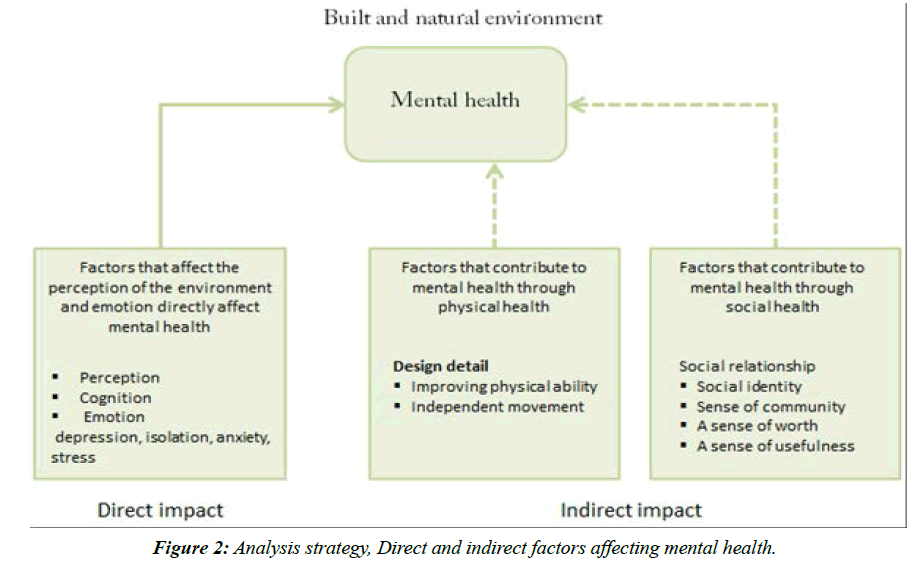

According to the American Psychiatric Association, emotions and cognitions (e.g. depressive thoughts) are related to mental health [11,12]. The environment can play an effective and direct role on mental health through emotions and cognitions and can play an indirect role through physical and social health. In research on the elderly, social health is determined through social relationships [12,13] and physical health is determined through physical activity and independence [6,14]

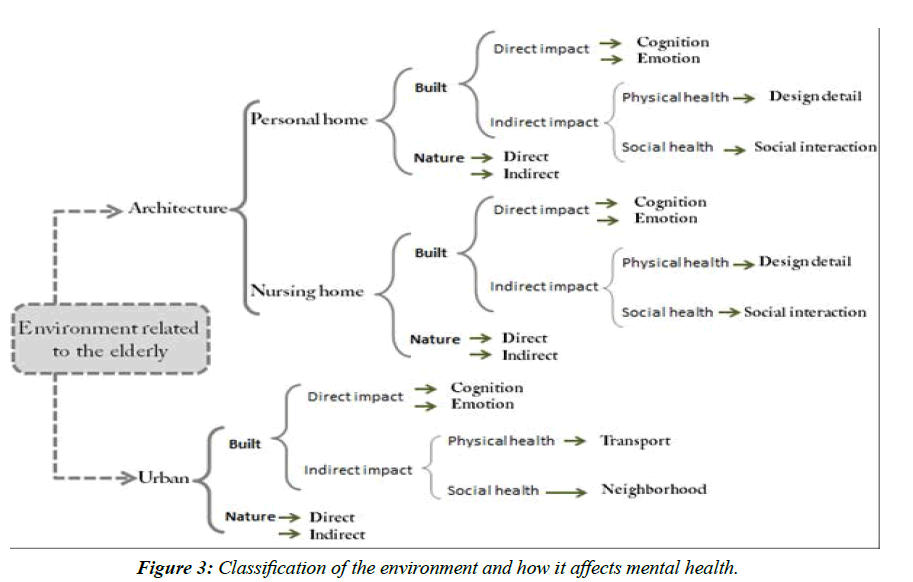

The built and natural environment related to elderly’s mental health can be examined according to two categories: architecture and urban. In this article, the architecture and urban literature in the fields of natural and built environment was analysed. The built architectural environment was then categorized into "personal home" and "nursing home" (Figure 2).

Built environment and mental health

Indirect impact on mental health through physical health: Rural-urban interface of the Bangalore (two transects) was defined as a common space for interdisciplinary research. The northern transect (N-transect) is a rectangular strip of 5 km width and 50 km length, the lower part of this transect cuts into urban Bangalore, and the upper part contains rural villages. The Southern transect (S-transect) is a polygon covering a total area of 300 km2. Rural-Urban interface was further divided into three sub regions viz., Rural, Transition and Urban areas based on the simplified Survey Stratification Index (SSI) by following the logic of the Urban-Rural Index which considered distance to the city centre (Vidhana Soudha) and percentage of built-up area [4]. This classification of regions, formed basis for selection of 300 middle income households based on purposive random sampling, in the rural-urban interface of Bangalore. In which 479 women and 474 men were assessed for nutritional status. Studies demonstrate that the environment can help the physical health of the elderly and pave the way for physical activity [15,16]. There are several factors in designing an environment that can encourage movement and physical activity [17-19]. Detailed design is effective in aspects of interiors such as lighting, furniture and form [20-22], and in exterior attention to access and support facilities of the building [16,19]. Studies have also been conducted on the built environment factors affecting the mental health of the elderly in nursing homes, including: Research into the factors that promote physical activity [16], interior design factors, attention to materials, facilities and service of the building and support facilities, acoustics, lighting, and indoor air quality [21-24].

In addition to architecture, urban spaces are a subset of built environments. The components of urban design that are most related to mental health have been studied in the categories of “transportation”, “neighbourhood” and “urban landscape”. There is a lot of research on the effect of walking on the physical and mental health of the elderly, which represents the route choice model and the influence of street characteristics on elderly walking for transport [25-27].

Indirect impact on mental health through social health: The importance of social interactions on mental health in residential areas of the elderly has been proven. Studies on the place of residence of the elderly show that older people want have choices about where and how they age in place homes and communities [27]. Jennifer Reichstadt et al. stated in 2007: “Older adults place greater emphasis on psychosocial factors as being key to successful aging, with less emphasis on factors such as longevity, genetics, and absence of disease/ disability, function, and independence.” This study shows that psychosocial factors are more important for the elderly than physical factors [28].

Another important factor is child proximity as shown by the research conducted. For instance, Hongwei, in his studies, states “Overall grandparents who cared for grandchildren had better mental and physical health, compared with non-caregivers. There was some evidence that the ‘sandwich’ grandparents who cared for both grandchildren and great-grandparents reported greater life satisfaction, fewer depressive symptoms, and reduced hypertension compared with non-caregivers” [29]. Also Williams declared: “intergenerational co-residence was found to have some positive health effects for older Chinese adults” [30].

When considering the urban category, residential neighborhood is also one of the most effective aspects of urban design for the mental health of the elderly. Social interactions and sense of community are important factors in supporting mental health [31-36]. Walkable environments and the possibility of physical activity in neighborhoods are other notable factors [37-44]. Feng states in his research that public transportation accessibility instead of auto transportation accessibility, vegetable markets instead of supermarkets and convenience stores, open spaces and parks along with chess and card rooms instead of gyms and sports centers are more decisive in affecting the travel behavior and mental health of the elderly [45]. Lauwers and colleagues also examined how neighborhood environment affects mental health and stated: “a detailed description of physical neighborhood factors (green-blue spaces, services, design and maintenance, traffic, cellphone towers) and social neighborhood factors (neighbor ties, neighbor diversity, social security) are linked to mental well-being”. In addition to the above, a number of studies have examined street characters characteristics for mental health, including the street as a place for social interaction [46].

The direct impact on mental health: The built and natural environment can directly affect mental health and contribute to the mental well-being of the elderly. In fact, the factors that affect perception of environment and emotions can eliminate the symptoms of depression, stress and nervous tension [47]. A review of the literature shows the relationship between interior detail and elderly mental health. Yajing Wang in his article describes how light exposure had little effect on the physiological rhythm of the elderly, but it did affect the visual performance and psychological feelings of the elderly [48]. In nursing homes, architectural factors influence the sense of home in nursing homes [49] and the design of mental and behavioral health facilities [50] play an important role in the mental health of the elderly. Design based on perception is an issue that is important in housing design. Marie Monique Paiva et al. demonstrate that understanding how people 'feel' spaces is fundamental to the person-environment relationship and its effects on mental health.

Natural environment and mental health

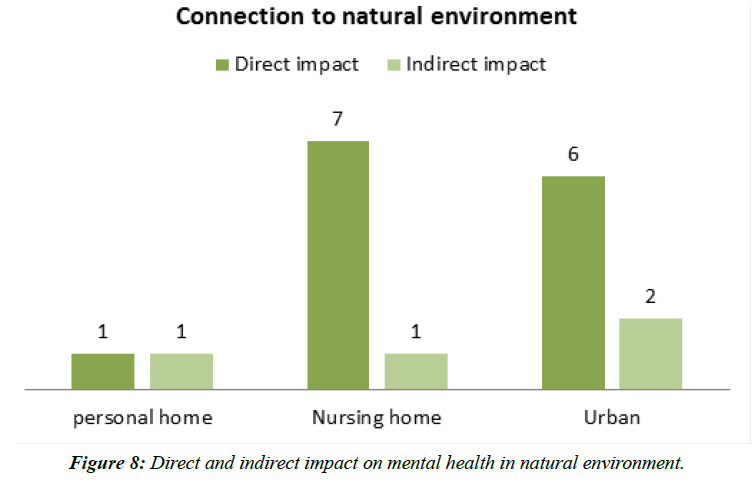

In addition to the built environment, the natural environment can also be effective (directly or indirectly) on mental health. Exposure to nature does have positive influences including improvements in physical health [51,52], mental health [51] and cognitive function [53], and social health [54]. Connection to nature is analyzed at three levels: personal home, nursing home and urban.

Studies have shown that the outdoor environment of a personal home for the elderly must consider nature, comfort, accessibility, mobility, and security [54-56]. Urban landscape and proximity to nature have been considered in many studies. According to these studies, neighborhood exposure to blue and green space was significantly associated with elderly individuals' mental health [57-59]. The health effects of viewing landscapes have been studied in the Velarde’s research [60]. In a number of studies, other effects of urban landscape on mental health are expressed, including: Extent of “eyes on the streets” on participant’s street, extent of variety of built form on participant’s street [61] and characteristics of a built-in residential environment that affects the mental health of adults such as walling materials used on buildings and, density of dwelling units [62].

Materials and Methods

Data collection method

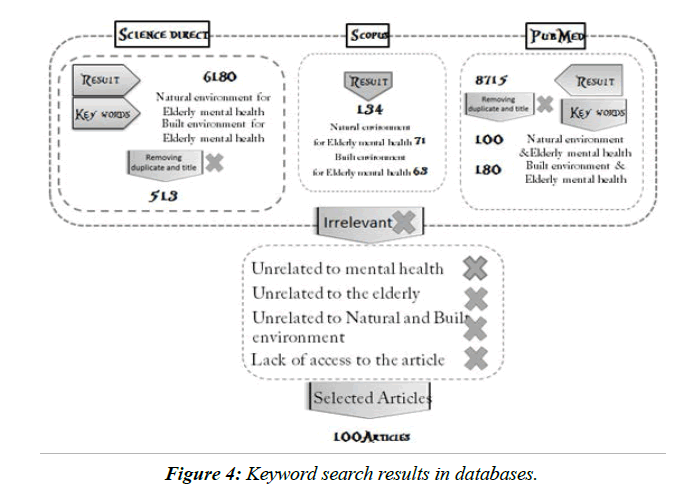

A literature search was conducted using Science Direct, Scopus, and PubMed to identify articles with two groups of keywords: one focusing on the “Mental Health of elderly and natural” and the second on “Mental health of elderly and built environment”

The results of the search were 6180 articles from Science Direct, 134 articles from Scopus, and 8715 articles from PubMed. The target period was 2000 to 2020; articles which were not directly or indirectly in the field of built and nature environments and the mental health of the elderly or were not in the desired time period were deleted. Finally, 100 articles remained and were used for review and meta-synthesis. Finally, results and percentages are obtained by averaging (Figures 3 and 4).

Method of Data Analysis

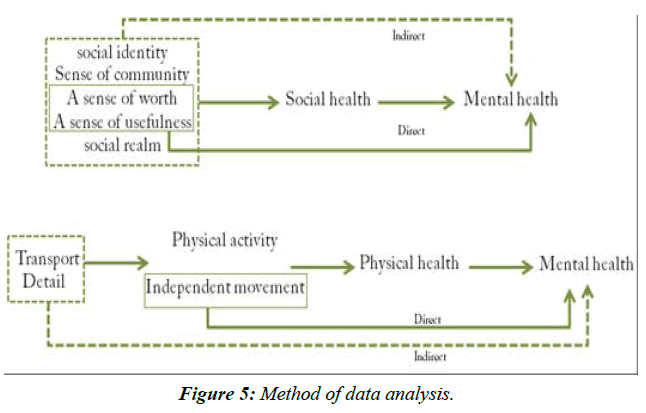

Qualitative analysis was carried out using, the meta-synthesis method. The aim of meta-synthesis is interpretive rather than deductive. The qualitative meta-synthesis method seeks to understand and explain phenomena [63]. Search results were categorized in two areas of architecture and urban spaces. The natural and built environment can affect mental health directly (cognition and emotion) (10] or indirectly (through social and physical health).

According to Theng’s research, social relationships are one of the most important factors that affect social health [64]. Social relationships free a person from isolation and subsequent depression by creating a sense of belonging to society and a sense of social identity. According to the WHO reports; Social health supports to mental health. As a result, all the factors of the natural and built environment that cause social relationships of the elderly contribute to the social health and thus have indirect effect on mental health. Also, interacting with others and accepting a role in society can help reduce depression by creating a sense of usefulness and worth, and thus have a direct effect on mental health [30,65] (Figure 4).

Many studies demonstrate that physical activity is one of the most important factors affecting physical health [15,66,67]. According to the WHO reports, physical health is very effective for mental health. As a result, any concept in the environment that helps promote physical activity and physical health can indirectly affect mental health. Also research has shown that independence in movement and physical activity is one of the factors that in addition to supporting physical health due to creating a sense of independence thus have a directly effect on mental health [14].

According to the above, design details in spaces related to the elderly, whether in private homes, care centres or urban spaces, which contribute to the physical activity and independent movement of the elderly, provide the basis for physical health and indirectly support mental health (Figure 2). In the following, we will review the studies conducted in these three areas of health and extract concepts from them.

Results

Figure 3 shows the numbers of publications identified, screened, assessed for eligibility and included. In total, 15029 articles were identified through database searching and checking reference lists. After removing duplicates and reviewing titles, 927 publications remained in the sample. Finally, by studying the abstracts and removing the unrelated items, 100 articles remained which formed the basis for the meta-synthesis review study. (Table provided in Supplementary file 1).

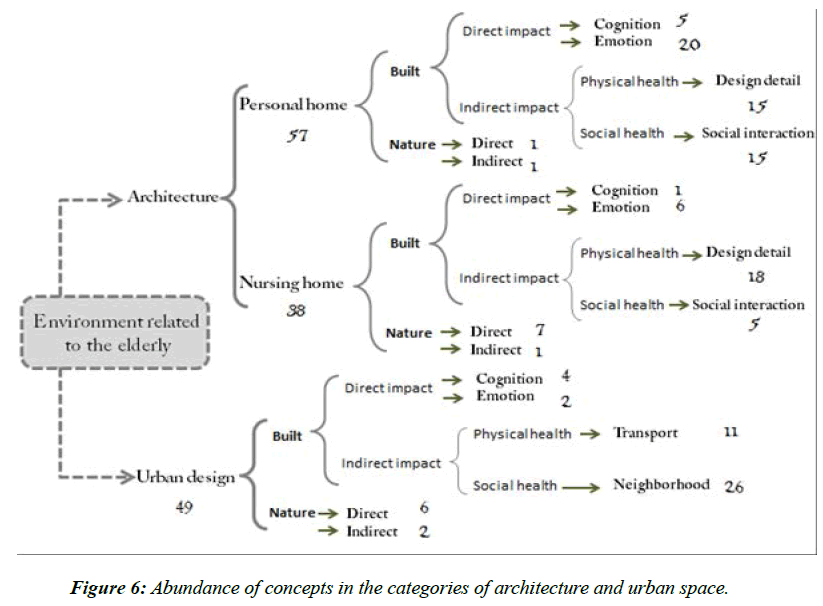

The selected research was classified into two general categories of architecture and urban that architectural articles were divided into two sections: “personal home” and “nursing home”.

In this study, the constructs were expressed in five categories which are known to a specific effect mechanism on mental health with direct and indirect effects. The following tables describe the mechanism of each construct and its effects on mental health.

Discussion

As described above, articles collected from 2000 to 2020 in the field of architecture and urban were divided into two categories of built and natural environment. The results of extracting concepts show the direct and indirect effects of natural and built environmental factors on mental health.

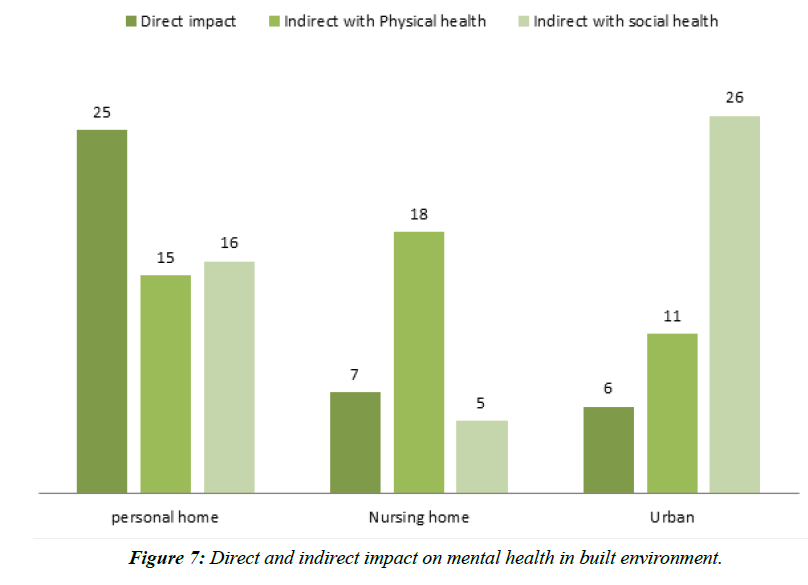

From a total of 100 articles reviewed, 144 factors were extracted, of which 30 factors covered two or three areas of health and factors related to mental health as follows: in the field of architecture and the subdivision of personal homes, 25 direct factors, 15 indirect factors (through physical health) and 15 indirect factors (through social health) and 2 natural factors with common effects on mental health were found. In nursing homes, 7 direct factors, 18 indirect factors (through physical health) and 5 indirect factors (through social health) and 8 natural factors with common effects on mental health were found. In the field of urban, 6 direct factors, 11 indirect factors through physical health and 26 indirect factors through social health and 8 natural factors with common effects on mental health were found (Figures 5 and 6).

Findings from previous research express the concepts that are created in the built and natural environment related to the elderly on their mental health. In this review, based on the concepts and factors extracted from the articles, two types of comparisons were made.

• Comparison between concepts and extracting the most effective concept supporting the mental health of the elderly.

• Comparing concepts in the environment related to the elderly and finding out how different types of environments affect mental health.

A review of articles conducted in the field of architecture and on the scale of the personal home of the elderly shows that environmental factors directly affect the mental health of the elderly. Factors such as built form, indoor space layout (private balcony, toilet, kitchen, and living room), external building characteristics, internal building environment, walling materials used on buildings, the quality of walling materials, light etc. (Table 1) These can directly lead to mental health improvements by reducing stress, anxiety and improving depression. In fact, the results suggest that in the personal homes of the elderly, the direct effects of environmental factors on mental health outweigh the indirect effects, as expressed by Wang in an article on the “Effect of light on health” whereby the short duration (i.e. 20 min) of light exposure had little effect on the physiological rhythm of the elderly, but it did affect the visual performance and psychological feelings of the elderly [20]. This may also be due to the emotional attachment to home and the sense of belonging to the place and neighbourhood mentioned in the article by Wiles et al [68]. Previous studies have shown that building factors are associated with mental health [69] and built environmental factors in homes directly affect mental health [27,47] (Figure 7).

| Construct | Mechanism | Result | Direct | Indirect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detail | · Improving physical ability | 1. light effect (1) | * | * | 1. Wang et al (2020) |

| 2. interior furniture (3,6) | |||||

| 3. lifts and water supply (3) | * | * | 2. Leung et al (2020) | ||

| 4. Areas available for walks (6) | * | 3. Leung et al (2020) | |||

| 5. locking the premises limit the ability (6) | * | 4,5,6,7. Mahrs Träff et al (2020) | |||

| 6. corridors (6) | * | 8. Li & Zhou (2020) | |||

| 7. dining room (6) | * | 9. Shikder et al(2012); Leung et al (2020) | |||

| 8. design of interior components of housing (7) | * | 10. Mahrs Träff et al (2020); Rodiek & Schwarz (2006) | |||

| 9. lighting design (10)(3) | * | 11. Jeste et al (2016) | |||

| 10. increased contact and activity levels with the outdoors (30,6) | * | ||||

| 11. safe outdoor (31) | |||||

| · Independent movement | 1. smart homes(5) | * | * | 1. Engineer et al (2018) | |

| 2. convenient transportation (31) | * | * | 2. Jeste et al (2016) | ||

| 3. building services and supporting facilities (4) | * | * | 3. Leung et al (2017) | ||

| 4. built form (9) | * | * | 4. Qiu et al (2020) | ||

| Social interaction | · social identity | 1. housing location (8) | * | 1,2,3. Friesinger et al (2019) | |

| 2. neighbourhood quality (8) | * | 4. De Belvis, et al (2008); Routasalo et al (2006) | |||

| 3. privacy and social identity (8) | * | 5. Laditka et al (2009) | |||

| 4. friends (18)(25) | * | ||||

| 5. socially involved (24) | * | ||||

| Sense of community | 1. age in place (12) | * | 1. Wiles et al(2012) | ||

| 2. intergenerational relationships (16) | * | 2. Shin (2014) | |||

| 3. intergenerational co-residence (17) | * | 3. Williams et al (2017) | |||

| 4. attachment to home (20) | 4,5. Wiles et al (2009) | ||||

| 5. neighborhood (20) | * | 6. Shin (2018) | |||

| 6. multi-family housing (23) | * | ||||

| · A sense of worth | 1. family social support (19) | * | * | 1. Li et al(2019) | |

| 2. social contacts (21)(22) | * | * | 2. Holmén & Furukawa (2002); Brown et al (2009) | ||

| ·A sense of usefulness | 1. proximity to grandparents and grandchildren (14) | * | * | 1. Xu (2019) | |

| 2. the role played by grandparents (15) | 2. Desiningrum (2018) | ||||

| 3. child proximity (17) | * | * | 3. Williams et al (2017) | ||

| cognition | Improve cognition ability | 1. built form (9) | * | 1. Qiu et al (2020) | |

| 2. attachment to home (20) | * | 2,3. Wiles et al (2009) | |||

| 3. attachment to neighborhood (20) | * | 4,5. Mercader-Moyano et al (2020) | |||

| 4. perceived quality in pathways and routes (27) | |||||

| 5. perceptions related to visual aesthetics (27) | * | ||||

| Emotion | Improve depression | 1. indoor space layout (Private balcony, toilet, kitchen, and living room) can reduce depression (7) | * | 1,2,3,4. Li & Zhou (2020) | |

| 2. external building characteristics (7) | 5,6. Liang (2020) | ||||

| 3. household facilities (7) | |||||

| 4. internal building environment (7) | * | ||||

| 5. number of floors (13) | * | ||||

| 6. high-quality houses (13) | * | ||||

| Reduce stress | 1. light effect (1) | * | 1.Wang et al (2020) | ||

| 2. built form (9) | * | 2. Qiu et al (2020) | |||

| 3. walling materials used on buildings (29) | * | 3-10. Ochodo et al (2014) | |||

| 4. density of dwelling units (29) | * | ||||

| 5. state of street lighting (29) | * | ||||

| 6. types of doors (29) | * | ||||

| 7. states of roofs (29) | * | ||||

| 8. states of windows (29) | * | ||||

| 9. the quality of walling materials (95) | |||||

| 10. density of dwelling units (95) | * | ||||

| Connection to nature | ·Encourage movement | 1. greenspace exposure89(28) | * | 1. De Keijzer et al (2020) | |

| · Reduce stress | 1. Interact with nature64(32) | * | 1. Orr et al (2016) |

Table 1. Constructs related to the elderly’s home shown to influence mental health outcomes.

This study found that supporting mental health through social and physical health in the personal home is of secondary importance. In personal home, it is possible to interact with friends, neighbours and family, which plays a very effective role in creating a sense of social identity. Paul et al. stated that “a community is a social unit of any size that shares common values, or that is situated in a given geographical area (e.g. a village or town)”. It is a group of people who are connected by durable relations that extend beyond immediate genealogical ties, and who mutually define that relationship as important to their social identity and practice [70]. Family support and interaction with the family can reduce depression [71] and create a sense of worth, and the role of grand parenting, proximity of grandparents and grandchildren [30] and caring for children and grandparents can create a sense of usefulness and thus support mental health [72].

In addition, older people want choices about where and how they age in place. “Aging in place” was seen as an advantage in terms of a sense of attachment or connection and feelings of security and familiarity in relation to both homes and communities. Aging in place related to a sense of identity both through independence and autonomy and through caring relationships and roles in the places people live [27]. Connection with nature in personal homes affects mental health both directly and indirectly (Figure 8). Nature encourages the elderly to move and be active by creating a sense of vitality. Also, interacting with nature also helps reduce stress, thus affecting both types of effect (direct and indirect) at the same time [55]. Areas available for walks, corridors, design of interior components of housing, lighting design and the outdoors increase contact and activity levels and this contributes to physical health.

One of the mechanisms that can create both types of impact at the same time is independence. Paying attention to design details that allow older people to move independently can improve depression by creating a sense of independence, and by encouraging older people to move contribute to their physical health. Smart Homes, convenient transportation, building services and supporting facilities, and built form can help create a sense of independence [18,73-75].

Unlike a private home, in nursing homes, environmental factors primarily support mental health indirectly through physical health. Factors such as space management, interior design factors, facilitate way finding, well-designed outdoor spaces and physical activity facilities encourage the elderly to move and be active. Also, acoustics, air quality, the indoor thermal climate, optimization of light and temperature adapts the space of the nursing home to the physical condition of the elderly and supports mental health by helping physical health. A review of research on nursing homes shows that environmental factors that can directly affect mental health are of secondary importance. One of the most important factors is having a private bedroom and personalization of the environment by the elderly and architectural factors that help reduce depression and isolation of the elderly by creating a sense of home [49,76,77]. Wang’s research suggests that reminiscence can help relieve depression [78]. On the other hand, the furniture used in care centres and the way they are arranged can create an intimate environment and provide a basis for reminiscence, and thus directly affect the mental health of the elderly. In addition to the entire above, positive technology, facilities and global design can help create a sense of independence and help improve depression and physical health of elderly (Figure 7).

In care centres, contact with nature has both direct and indirect effects. The results show that horticultural therapy improves physical function and reduces stress, and also supports social health due to social interaction with other elderly people [79]. Green spaces, gardens and lakes also play a supporting role in reducing stress (Figure 8).

In urban spaces (neighbourhoods and transportation routes), social health is the most effective component supporting mental health. Open spaces and parks along with chess, a walkable environment characterized by a high population density and proximate local, public transportation, mixed land use, eyes on the streets etc. (Tables 2 and 3) are factors that contribute to social health by creating the conditions for social interaction and thus support mental health. In urban spaces, there are also factors that contribute to social health by creating a sense of belonging to society, such as public transport, residential environment of neighbourhood, proximity to a wet market, aesthetics and natural space [31,38,80-85]. Having a social realm can also contribute to social health. A view from home to neighbourhood, neighbourhood security, neighbourhood services, public open space, etc. can help create a social realm [33,34,86-90]. The importance of social health has been proven in previous studies. Reichstadt et al. stated that older adults place greater emphasis on psychosocial factors as being key to successful aging [28,91-95] (Figure 7).

| Construct | Mechanism | Result | Direct | indirect | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detail | Improving physical ability | 1. facilitate way finding (36) | * | 1. Ludden et al (2019) | |

| 2. areas available for walks (6) | * | 2,3,4,5. Mahrs Träff (2020) | |||

| 3. locking the premises limit the ability (6) | * | 6. Anme et al (2013) | |||

| 4. corridors (6) | * | 7. Leung et al (2020) | |||

| 5. dining room (6) | * | 8,9. Leung et al (2019) | |||

| 6. wood (41) | * | 10,11,12,13. Roelofsen (2014) | |||

| 7. interior design factors (43) | * | 14. Zadeh et al (2018) | |||

| 8. space management (38) | * | 15. Othman & Fadzil (2015) | |||

| 9. building services and supporting facilities (38) | * | ||||

| 10. acoustics (40) | * | ||||

| 11. light (40) | |||||

| 12. air quality (40) | * | ||||

| 13. the indoor thermal climate (40) | |||||

| 14. optimization of light and temperature (45) | |||||

| 15. well-designed outdoor spaces (53) | |||||

| Independent movement | 1. positive technology (33) | * | * | 1. Grossi et al (2020) | |

| 2. facilities (35) | * | * | 2. Anthony & McCaffrey (2018) | ||

| 3. universal design (46) | * | * | 3. Mustaquim MM. (2015) | ||

| Social interaction | social identity | - | |||

| Sense of community (social engagement) | 1. environmental design (36) | * | * | 1. Ludden et al (2019) | |

| 2. wood (41) | * | 2. Anme et al (2013) | |||

| social realm | 1. Courtyards (44) | * | 1. Mohammad et al (2016) | ||

| 2. choices of bedrooms (44)(47) | * | 2. Mohammad et al (2016); Paiva et al (2015) | |||

| 3. furniture (3) | * | 3. Leung et al (2020) | |||

| Cognition | Improve cognition ability | 1- feel of environment (47) | 1. Paiva et al (2015) | ||

| Emotion | Improve depression | 1. reminiscence (2) | * | 1. Wang et al (2005) | |

| 2. furniture (3) | 2. Leung et al (2020) | ||||

| Reduce stress | 1. architectural factors (34) | * | 1. Eijkelenboom et al (2017) | ||

| the sense of home | 2. bedroom privacy (39) | * | 2. Tao et al (2018) | ||

| 3. privacy personalization (45) | * | 3. Zadeh et al (2018) | |||

| 4. comfort98(47) | * | 4. Paiva et al (2015) | |||

| Connection to nature | Physical (improved physical ability) |

1. horticultural therapy (48) | * | 1. Chan et al (2017) | |

| Mental (Reduce stress) |

1. horticultural therapy (49) | * | 1. Han et al (2018) | ||

| 2. Greenspace interventions (50) | * | 2. Masterton et al (2020) | |||

| 3. Exposure to greenery and use of greenspace (51) | * | 3. Carver et al (2020) | |||

| 4. Parks (96) | * | 4,5,6,7. Finlay et al (2015) | |||

| 5. Gardens (96) | * | ||||

| 6. street greenery (96) | * | ||||

| 7. lakes (96) |

Table 2. Constructs related to the elderly’s nursing home shown to influence mental health outcomes.

| Construct | Mechanism | Result | Direct | indirect | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport | Improving physical ability | 1. street characteristics (54) | * | 1. Hatamzadeh & Hoseinzadeh (2020) | |

| 2. walking for transport (55)(56) | * | 2. Borst et al (2009); Cheng et al (2020) | |||

| 3. land use (57) | * | 3. Frank et al (2019) | |||

| 4. walkable environment (65)(72)(77)(80)(83) | * | 4.Koohsari et al (2019); Loo et al (2017)a; Chaudhury et al (2016); Bird et al (2018); Balfour & Kaplan (2002) | |||

| 5. accessibility (78) | 5.Gao et al (2016) | ||||

| Independent movement | 1. pedestrian networks (58) | * | * | 1.Gaglione et al (2020) | |

| 2. accessible homes (61) | * | * | 2.Oswald et al (2002) | ||

| 3. short distance access to vehicles (86) | * | * | 3.Fernández-Niño et al (2019) | ||

| 4. commerce and mixed land use (71) | * | * | 4.Danielewicz et al (2018) | ||

| 5. a road network buffer had (82) | 5.Melis et al (2015) | ||||

| 6. Predominant setback of buildings from street (97) | * | * | 6.Burton et al (2011) | ||

| Residential neighborhood | Social interaction | 1. open spaces and parks along with chess instead of gyms and sports centers (66) | * | 1.Feng (2017) | |

| 2. feeling safe from traffic (68) | 2,3,4.Gómez et al (2010) | ||||

| 3. areas with middle park area (68) | * | 5.Levasseur et al (2015) | |||

| 4. quality of the sidewalks (68) | * | 6.Koohsari et al (2019) | |||

| 5. social participation (81) | 7. Feng (2017) | ||||

| 6. walkable environment characterized by a high population density and proximate local (65) | 8,9. Danielewicz et al (2018) | ||||

| 7. public transportation (66) | * | 10.Lauwers et al (2020) | |||

| 8. commerce land (71) | 11. Loo et al (2017)b | ||||

| 9. mixed land use (71) | * | 12.Chen & Yuan (2020) | |||

| 10. social security (84) | * | 13. Burton et al(2011) | |||

| 11. walkable environment (88) | * | ||||

| 12. exposure to the especially blue space (90) | * | ||||

| 13. eyes on the streets (97) | * | ||||

| Sense of community(social engagement) | 1. land use (57) | * | 1. Frank et al (2019) | ||

| 2. public transport (59) | * | 2. Melis et al (2015) | |||

| 3. residential environment of neighborhood (62)(67)(71)(72)(73)(77)(83) | * | 3. Zhang & Zhang (2017); Mohammad & Abbas(2012); Danielewicz et al (2018); Loo et al (2017)b; Walker & Hiller(2007); Chaudhury et al (2016); Balfour & Kaplan(2002) | |||

| 4. walkable environments (69)(70) | 4. Marquet & Miralles-Guasch (2015); Distefano et al (2020) | ||||

| 5. proximity to a wet market (85) | 5. Lane et al (2020) | ||||

| 6. aesthetics (87) | * | 6. Zhao & Chung (2017) | |||

| 7. natural space (92) | * | 7. Rugel et al (2019) | |||

| social realm | 1. observed from the home (74) | * | 1. Lager et al (2015) | ||

| 2. neighborhood security (75) | 2,3,4. Cramm et al (2013) | ||||

| 3. neighborhood services (75) | * | 5. Francis et al (2013) | |||

| 4. neighborhood social capital (75) | * | 6. Qiu et al (2019) | |||

| 5. public open space (79) | * | ||||

| 6. Safety (82) | |||||

| cognition | Improve cognition ability | 1. different urban environments (60) | * | 1. Tilley et al (2017) | |

| 2. subjective indicators (64) | * | 2. Dujardin et al (2014) | |||

| 3. safety (78)(99) | * | 3. Gao et al (2016); Wang et al (2019) | |||

| 4. variety of built form (98) | * | 4. Nishigaki et al (2020) | |||

| Emotion | Improve depression | 1. independence (63) | * | 1. El-Gilany et al (2018) | |

| Reduce stress | 2. building configurations (91) | * | 2. Zhifeng & Yin (2020) | ||

| Connection to nature (physical) | Physical • improved physical ability | 1. urban green and blue spaces (89) | * | 1. El-Gilany et al (2018) | |

| 2. street environment (94) | * | 2. Kabisch et al (2020) | |||

| Mental • Reduced stress • Stimulation of the senses |

1. urban green and blue spaces (84)(89) | * | * | 1. Lauwers et al (2020); Kabisch et al (2017) | |

| 2. exposure to the especially blue space (90) | * | 2. Chen & Yuan (2020) | |||

| 3. viewing landscape (93) | * | 3. Velarde et al (2007) | |||

| 4. tree density (98) | * | 4,5. Nishigaki et al (2020) | |||

| 5. rural areas (98) | 6. Liu et al (2020) | ||||

| 6. water space (100) |

Table 3. Constructs related to urban shown to influence mental health outcomes.

Considering the urban category, the impact of environmental factors on physical health is of secondary importance. Street characteristics, a walkable environment and accessibility are among the items that contribute to physical health and indirectly to mental health by providing physical activity conditions. Also, pedestrian networks, accessible homes, short distance access to vehicles, a road network buffer and predominant setback of buildings from street are cases that support physical, social, and mental health by helping the elderly to move independently [96-101]. Urban green and blue spaces, viewing landscape, tree density and rural areas have a direct impact on mental health (Figure 8) [102-109].

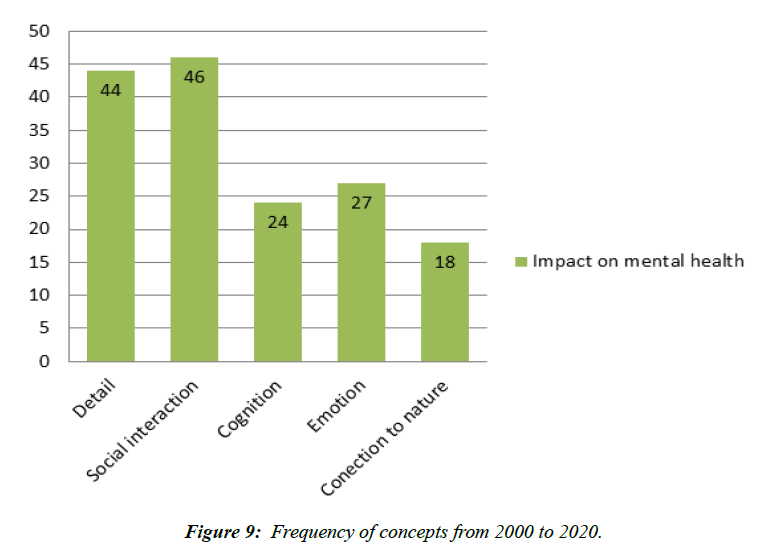

Examining the frequency of concepts in all environments related to the elderly also indicates that, in general, the greatest effects of environment on mental health are indirectly through the provision of social interactions (Figures 9 and 10) [110-117].

- World Health Organization. (2013). Mental health action plan 2013-2020.

- Lee BX, Kjaerulf F, Turner S, et al. Transforming our world: implementing the 2030 agenda through sustainable development goal indicators. J Public Health Policy. 2016;37(1):13-31.

- Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, et al. Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2008; 165(6):703-11.

- Friedrich MJ. Depression is the leading cause of disability around the world. Jama. 2017; 317(15):1517.

- World Health Organization. The world health report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life. World Health Organization. 2002.

- El-Gilany AH, Elkhawaga GO, Sarraf BB. Depression and its associated factors among elderly: A community-based study in Egypt. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2018; 77:103-7.

- Oswald F, Wahl HW, Schilling O, et al. Relationships between housing and healthy aging in very old age. The Gerontologist. 2007; 47(1):96-107.

- Shin JH. Listen to the elders: design guidelines for affordable multifamily housing for the elderly based on their experiences. J Hous Elderly. 2018; 32(2):211-40.

- Maciel MG. Physical activity and functionality of the elderly. J Teach Phys Educ. 2010; 16(4):1024-32.

- Nahas MV. Atividade física, saúde e qualidade de vida. Londrina: Midiograf. 2001; 3:278..

- Beemer CJ, Stearns-Yoder KA, Schuldt SJ, et al. A brief review on the mental health for select elements of the built environment. Indoor Built Environ. 2021; 30(2):152-65.

- Vahia VN. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5: A quick glance. Indian J. Psychiatry. 2013; 55(3):220.

- Brown SC, Mason CA, Lombard JL, et al. The relationship of built environment to perceived social support and psychological distress in Hispanic elders: The role of “eyes on the street”. J Gerontol B. 2009; 64(2):234-46.

- Bloom JR. The relationship of social support and health. Soc Sci. 1990; 30(5):635-7.

- Sun F, Norman IJ, While AE. Physical activity in older people: a systematic review. BMC public health. 2013; 13(1):1-7.

- Mahrs Träff A, Cedersund E, Abramsson M. What Promotes and What Limits Physical Activity in Assisted Living Facilities? A Study of the Physical Environment’s Design and Significance. Journal of Aging and Environment. 2020; 34(3):291-309.

- Rodiek S, Schwarz B. The role of the outdoors in residential environments for aging. Routledge. 2006.

- Engineer A, Sternberg EM, Najafi B. Designing interiors to mitigate physical and cognitive deficits related to aging and to promote longevity in older adults: a review. Gerontology. 2018; 64(6):612-22.

- Ruengtam P. Factor analysis of built environment design and management of residential communities for enhancing the wellbeing of elderly people. Procedia Eng. 2017; 180:966-74.

- Jeste DV, Blazer II DG, Buckwalter KC, et al. Age-friendly communities initiative: public health approach to promoting successful aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016; 24(12):1158-70.

- Wang Y, Huang H, Chen G. Effects of lighting on ECG, visual performance and psychology of the elderly. Optik. 2020:164063.

- Leung MY, Wang C, Wei X. Structural model for the relationships between indoor built environment and behaviors of residents with dementia in care and attention homes. Building and Environment. 2020; 169:106532.

- Shikder S, Mourshed M, Price A. Therapeutic lighting design for the elderly: a review. Perspect Public Health. 2012; 132(6):282-91.

- Anme T, Tanaka E, Watanabe T, et al. Wood products improve the quality of life of elderly people in assisted living. Int. Multidiscip. Sci. GeoConference. 2013:515.

- Roelofsen P. Healthy ageing-Design criteria for the indoor environment for vital elderly. Intell Build Int. 2014; 6(1):11-25.

- Hatamzadeh Y, Hosseinzadeh A. Toward a deeper understanding of elderly walking for transport: An analysis across genders in a case study of Iran. J Transp Health. 2020; 19:100949.

- Borst HC, de Vries SI, Graham JM, et al. Influence of environmental street characteristics on walking route choice of elderly people. J Environ Psychol. 2009; 29(4):477-84.

- Wiles JL, Leibing A, Guberman N, et al. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. The gerontologist. 2012; 52(3):357-66.

- Reichstadt J, Depp CA, Palinkas LA, et al. Building blocks of successful aging: a focus group study of older adults' perceived contributors to successful aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007; 15(3):194-201..

- Xu H. Physical and mental health of Chinese grandparents caring for grandchildren and great-grandparents. Soc Sci. 2019; 106-16.

- Williams L, Zhang R, Packard KC. Factors affecting the physical and mental health of older adults in China: The importance of marital status, child proximity, and gender. SSM - Population Health. 2017; 3:20-36.

- Zhang Z, Zhang J. Perceived residential environment of neighborhood and subjective well-being among the elderly in China: A mediating role of sense of community. J Environ Psychol. 2017; 51:82-94.

- Walker RB, Hiller JE. Places and health: A qualitative study to explore how older women living alone perceive the social and physical dimensions of their neighbourhoods. Soc Sci Med. 2007; 65(6):1154-65.

- Lager D, Van Hoven B, Huigen PP. Understanding older adults’ social capital in place: Obstacles to and opportunities for social contacts in the neighbourhood. Geoforum. 2015; 59:87-97.

- Cramm JM, Van Dijk HM, Nieboer AP. The importance of neighborhood social cohesion and social capital for the well being of older adults in the community. The Gerontologist. 2013; 53(1):142-52.

- Levasseur M, Généreux M, Bruneau JF, et al. Importance of proximity to resources, social support, transportation and neighborhood security for mobility and social participation in older adults: results from a scoping study. BMC public health. 2015; 15(1):1-9.

- Lauwers L, Leone M, Guyot M, et al. Exploring how the urban neighborhood environment influences mental well-being using walking interviews. Health & Place. 2021; 67:102497.

- Koohsari MJ, McCormack GR, Nakaya T, et al. Urban design and Japanese older adults' depressive symptoms. Cities. 2019; 87:166-73.

- Mohammad NM, Abbas MY. Elderly environment in Malaysia: Impact of multiple built environment characteristics. Procedia Soc. 2012; 49:120-6.

- Gómez LF, Parra DC, Buchner D, et al. Built environment attributes and walking patterns among the elderly population in Bogotá. Am. J Prev Med. 2010; 38(6):592-9.

- Distefano N, Pulvirenti G, Leonardi S. Neighbourhood walkability: Elderly's priorities. Res Transp Bus Manag. 2021; 40:100547.

- Lam WW, Loo BP, Mahendran R. Neighbourhood environment and depressive symptoms among the elderly in Hong Kong and Singapore. Int J Health Geogr. 2020; 19(1):1-0.

- Loo BP, Lam WW, Mahendran R, et al. How is the neighborhood environment related to the health of seniors living in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Tokyo? Some insights for promoting aging in place. Annals of the American Association of Geographers. 2017; 107(4):812-28.

- Bird EL, Ige JO, Pilkington P, et al. Built and natural environment planning principles for promoting health: an umbrella review. BMC public health. 2018; 18(1):1-3.

- Chaudhury H, Campo M, Michael Y, et al. Neighbourhood environment and physical activity in older adults. Soc Sci Med. 2016; 149:104-13.

- Feng J. The influence of built environment on travel behavior of the elderly in urban China. Transp Res D Transp Environ. 2017; 52:619-33.

- Frank LD, Iroz-Elardo N, MacLeod KE, et al. Pathways from built environment to health: A conceptual framework linking behavior and exposure-based impacts. Journal of Transport & Health. 2019; 12:319-35.

- Li C, Zhou Y. Residential environment and depressive symptoms among Chinese middle-and old-aged adults: A longitudinal population-based study. Health & Place. 2020; 66:102463.

- Li X, Wang X. Relationships between stroke, depression, generalized anxiety disorder and physical disability: Some evidence from the Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health. Psychiatry Res. 2020; 290: 113074.

- Eijkelenboom A, Verbeek H, Felix E, et al. Architectural factors influencing the sense of home in nursing homes: An operationalization for practice. Front Archit Res. 2017; 6(2):111-22.

- Anthony KH, McCaffrey K. Designing Mental and Behavioral Health Facilities: Psychological, Social, and Cultural Issues. InEnvironmental Psychology and Human Well-Being 2018; 335-363. Academic Press.

- Pretty J. How nature contributes to mental and physical health. Spirituality and Health International. 2004; 5(2):68-78.

- Björk J, Albin M, Grahn P, et al. Recreational values of the natural environment in relation to neighbourhood satisfaction, physical activity, obesity and wellbeing. J Epidemiology Commu. 2008; 62(4):e2.

- Sugiyama T, Leslie E, Giles-Corti B, et al. Associations of neighbourhood greenness with physical and mental health: do walking, social coherence and local social interaction explain the relationships?. J Epidemiology Community Health. 2008; 62(5):e9.

- Bratman GN, Hamilton JP, Daily GC. The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012; 1249(1):118-36.

- Mercader-Moyano P, Flores-García M, Serrano-Jiménez A. Housing and neighbourhood diagnosis for ageing in place: Multidimensional Assessment System of the Built Environment (MASBE). Sustainable cities and society. 2020; 62:102422.

- de Keijzer C, Bauwelinck M, Dadvand P. Long-term exposure to residential greenspace and healthy ageing: A systematic review. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2020; 7(1):65-88.

- Orr N, Wagstaffe A, Briscoe S, et al. How do older people describe their sensory experiences of the natural world? A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. BMC geriatrics. 2016; 16(1):1-6.

- Chen Y, Yuan Y. The neighborhood effect of exposure to blue space on elderly individuals’ mental health: A case study in Guangzhou, China. Health & Place. 2020; 63:102348.

- Rugel EJ, Carpiano RM, Henderson SB, et al. Exposure to natural space, sense of community belonging, and adverse mental health outcomes across an urban region. Environ Res. 2019; 171:365-77.

- Liu Y, Wang R, Lu Y, et al. Natural outdoor environment, neighbourhood social cohesion and mental health: Using multilevel structural equation modelling, streetscape and remote-sensing metrics. Urban For Urban Green. 2020; 48:126576.

- Velarde MD, Fry G, Tveit M. Health effects of viewing landscapes–Landscape types in environmental psychology. Urban For Urban Green. 2007; 6(4):199-212.

- Burton EJ, Mitchell L, Stride CB. Good places for ageing in place: development of objective built environment measures for investigating links with older people's wellbeing. BMC public health. 2011; 11(1):1-3.

- Ochodo C, Ndetei DM, Moturi WN, et al. External built residential environment characteristics that affect mental health of adults. J Urban Health. 2014; 91(5):908-27.

- Walsh D, Downe S. Meta?synthesis method for qualitative research: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005; 50(2):204-11.

- World Health Organization, 2020. World Report of Physical Health.

- Theng YL, Chua PH, Pham TP. Wii as entertainment and socialisation aids for mental and social health of the elderly. InCHI'12 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2012; 691-702.

- Liang Y. Heterogeneity in the trajectories of depressive symptoms among elderly adults in rural China: The role of housing characteristics. Health & place. 2020; 66:102449.

- Garin N, Olaya B, Miret M, et al. Built environment and elderly population health: a comprehensive literature review. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health: CP & EMH. 2014; 10:103.

- Wiles JL, Allen RE, Palmer AJ, et al. Older people and their social spaces: A study of well-being and attachment to place in Aotearoa New Zealand. Soc Sci Med. 2009; 68(4):664-71.

- James P, Nadarajah Y, Haive K, et al. Sustainable communities, sustainable development: other paths for Papua New Guinea. University of Hawaii Press; 2012.

- Paul DR. Polymer Blends Volume 1. Elsevier; 2012.

- Li C, Jiang S, Zhang X. Intergenerational relationship, family social support, and depression among Chinese elderly: A structural equation modeling analysis. J Affect Disord. 2019; 248:73-80.

- Desiningrum DR. Grandparents' roles and psychological well-being in the elderly: a correlational study in families with an autistic child. Enfermeria clinica. 2018; 28:304-9.

- Wang R, Liu Y, Lu Y, et al. Perceptions of built environment and health outcomes for older Chinese in Beijing: A big data approach with street view images and deep learning technique. Comput Environ Urban Syst. 2019; 78:101386.

- Qiu QW, Li J, Li JY, et al. Built form and depression among the Chinese rural elderly: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 2020; 10(12):e038572.

- Friesinger JG, Topor A, Bøe TD, etL. Studies regarding supported housing and the built environment for people with mental health problems: A mixed-methods literature review. Health & place. 2019; 57:44-53.

- Tao Y, Lau SS, Gou Z, et al. Privacy and well-being in aged care facilities with a crowded living environment: case study of hong kong care and attention homes. Int J Environ Res. 2018; 15(10):2157.

- Zadeh RS, Eshelman P, Setla J, et al. Environmental design for end-of-life care: An integrative review on improving the quality of life and managing symptoms for patients in institutional settings. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018; 55(3):1018-34.

- Wang JJ, Hsu YC, Cheng SF. The effects of reminiscence in promoting mental health of Taiwanese elderly. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005; 42(1):31-6.

- Han AR, Park SA, Ahn BE. Reduced stress and improved physical functional ability in elderly with mental health problems following a horticultural therapy program. Complement Ther Med. 2018 ; 38:19-23.

- Francis J, Wood LJ, Knuiman M, et al. Quality or quantity? Exploring the relationship between Public Open Space attributes and mental health in Perth, Western Australia. Soc Sci. 2012; 74(10):1570-7.

- Balfour JL, Kaplan GA. Neighborhood environment and loss of physical function in older adults: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2002; 155(6):507-15.

- Carver A, Lorenzon A, Veitch J, et al. Is greenery associated with mental health among residents of aged care facilities? A systematic search and narrative review. Aging Ment Health. 2020; 24(1):1-7.

- Chan HY, Ho RC, Mahendran R, et al. Effects of horticultural therapy on elderly’health: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC geriatrics. 2017; 17(1):1-0.

- Cheng L, De Vos J, Zhao P, et al. Examining non-linear built environment effects on elderly’s walking: A random forest approach. Transp Res D Transp Environ. 2020; 88:102552.

- Danielewicz AL, d'Orsi E, Boing AF. Association between built environment and the incidence of disability in basic and instrumental activities of daily living in the older adults: Results of a cohort study in southern Brazil. Prev Med. 2018; 115:119-25.

- de Belvis AG, Avolio M, Spagnolo A, et al. Factors associated with health-related quality of life: the role of social relationships among the elderly in an Italian region. Public health. 2008; 122(8):784-93.

- Dujardin C, Lorant V, Thomas I. Self-assessed health of elderly people in Brussels: Does the built environment matter?. Health & place. 2014; 27:59-67.

- Fernández-Niño JA, Bonilla-Tinoco LJ, Manrique-Espinoza BS, et al. Neighborhood features and depression in Mexican older adults: A longitudinal analysis based on the study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE), waves 1 and 2 (2009-2014). PloS one. 2019; 14(7):e0219540.

- Finlay J, Franke T, McKay H, et al. Therapeutic landscapes and wellbeing in later life: Impacts of blue and green spaces for older adults. Health & place. 2015; 34:97-106.

- Gaglione F, Cottrill C, Gargiulo C. Urban services, pedestrian networks and behaviors to measure elderly accessibility. Transp Res D Transp Environ. 2021; 90:102687.

- Gao M, Ahern J, Koshland CP. Perceived built environment and health-related quality of life in four types of neighborhoods in Xi’an, China. Health & place. 2016; 39:110-5.

- Grossi G, Lanzarotti R, Napoletano P, et al. Positive technology for elderly well-being: A review. Pattern Recognit Lett. 2020; 137:61-70.

- Holmén K, Furukawa H. Loneliness, health and social network among elderly people—a follow-up study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002; 35(3):261-74.

- Kabisch N, van den Bosch M, Lafortezza R. The health benefits of nature-based solutions to urbanization challenges for children and the elderly–A systematic review. Environ Res. 2017; 159:362-73.

- Kabisch N, Pueffel C, Masztalerz O, et al. Physiological and psychological effects of visits to different urban green and street environments in older people: A field experiment in a dense inner-city area. Landsc Urban Plan. 2021; 207:103998.

- Laditka SB, Corwin SJ, Laditka JN, et al. Attitudes about aging well among a diverse group of older Americans: Implications for promoting cognitive health. The Gerontologist. 2009; 49(S1):S30-9.

- Lane AP, Hou Y, Wong CH, et al. Cross-sectional associations of neighborhood third places with social health among community-dwelling older adults. Soc Sci. 2020; 258:113057.

- Leung MY, Wang C, Chan IY. A qualitative and quantitative investigation of effects of indoor built environment for people with dementia in care and attention homes. Build Environ. 2019; 157:89-100.

- Leung MY, Famakin I, Kwok T. Relationships between indoor facilities management components and elderly people's quality of life: A study of private domestic buildings. Habitat Int. 2017; 66:13-23.

- Ludden GD, van Rompay TJ, Niedderer K, et al. Environmental design for dementia care-towards more meaningful experiences through design. Maturitas. 2019; 128:10-6.

- Marquet O, Miralles-Guasch C. Neighbourhood vitality and physical activity among the elderly: The role of walkable environments on active ageing in Barcelona, Spain. Soc Sci. 2015; 135:24-30.

- Masterton W, Carver H, Parkes T, et al. Greenspace interventions for mental health in clinical and non-clinical populations: What works, for whom, and in what circumstances?. Health & Place. 2020; 64:102338.

- Melis G, Gelormino E, Marra G, et al. The effects of the urban built environment on mental health: A cohort study in a large northern Italian city. Int J Environ Res. 2015; 12(11):14898-915.

- Mohammad SA, Dom MM, Ahmad SS. Inclusion of social realm within elderly facilities to promote their wellbeing. Procedia Soc. 2016; 234:114-24.

- Mustaquim MM. A study of Universal Design in everyday life of elderly adults. Procedia Comput Sci. 2015; 67:57-66.

- Nishigaki M, Hanazato M, Koga C, et al. What types of greenspaces are associated with depression in urban and rural older adults? A multilevel cross-sectional study from JAGES. Int J Environ Res. 2020; 17(24):9276.

- Othman AR, Fadzil F. Influence of outdoor space to the elderly wellbeing in a typical care centre. Procedia Soc. 2015; 170:320-9.

- Paiva MM, Sobral ER, Villarouco V. The elderly and environmental perception in collective housing. Procedia Manuf. 2015; 3:6505-12.

- Qiu Y, Liu Y, Liu Y, et al. Exploring the linkage between the neighborhood environment and mental health in Guangzhou, China. Int J Environ Res. 2019; 16(17):3206.

- Routasalo PE, Savikko N, Tilvis RS, et al. Social contacts and their relationship to loneliness among aged people–a population-based study. Gerontol. 2006; 52(3):181-7.

- Sanjay TV, Yannick PP, Madhusudan M, et al. Depression and its associated factors among elderly patients attending rural primary health care setting. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2017; 4(2):471.

- Shin JH. The residential choices of ethnic elders in affordable housing: Changing intergenerational relationships and the pursuit of residential independence. J Hous Elder. 2014; 28(2):221-42.

- Tilley S, Neale C, Patuano A, et al. Older people’s experiences of mobility and mood in an urban environment: A mixed methods approach using electroencephalography (EEG) and interviews. Int J Environ Res. 2017; 14(2):151.

- Zhao Y, Chung PK. Neighborhood environment walkability and health-related quality of life among older adults in Hong Kong. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics. 2017; 73:182-6.

- Zhifeng W, Yin R. The influence of greenspace characteristics and building configuration on depression in the elderly. Build Environ. 2021; 188:107477.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref