- Biomedical Research (2014) Volume 25, Issue 1

Diabetes risk 10 years forecast in the capital of Saudi Arabia: Canadian Diabetes Risk Assessment Questionnaire (CANRISK) perspective.

Ahmad Alghadir1, Hamzeh Awada1*, Einas Al-Eis2, Alia Alghwiri21Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

2Department of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, The University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan

- *Corresponding Author:

- Hamzeh Awad

Rehabilitation Research Chair

Saudi Arabia

King Saud University

P.O. Box 2925, Riyadh 11461

Accepted November 14 2013

Abstract

The prevalence of diabetes type 2 (DMT2) in Saudi Arabia has been increased dramatically. The early detection of diabetes is crucial in delaying the process of the disease. The Canadian Risk (CANRISK) is a self-administered questionnaire used to identify people at high risk for developing diabetes. The main objective of this study was to utilize the CANRISK to evaluate the diabetes risk among participants in the capital of Saudi Arabia (Riyadh). In this cross-sectional study design, the CANRISK was administered to a convenience sample of people (603) in Riyadh by healthcare professionals. Six hundred and three participants were recruited from public areas of Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, to participate in this study. The mean total CANRISK score for this study was 33.24(SD±11.36) with a range from 9 to 68. Women had significantly higher CANRISK total scores than did men in both moderate and high risk categories. High CANRISK score is emphasizing that more than half of the study participants have high risk for developing DMT2. Thus, urge the need for efforts to minimize sedentary lifestyle in Saudi general population.

Keywords

Diabetes Mellitus (DM), Canadian Risk (CANRISK), Body Mass Index (BMI), Prediabetes, Screening

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes has been increasing enormously at an alarming rate worldwide. Worldwide approximately 366 million people suffer from diabetes mellitus in 2011, some 80% of whom live in low- and ]. Prevalence of diabetes in 1middle-income countries [ Saudi Arabia is among the highest globally, affecting 23.7% of the Saudi population [2].

Despite high rates of undiagnosed diabetes and prediabetes in Middle East, the assessment tools currently used to estimate an individual’s risk of diabetes are lacking. It is clinically important to be able to identify individuals at risk of diabetes. First, undiagnosed diabetes often remains undetected for 4 to 7 years before clinical diagnosis, and many newly diagnosed patients already exhibit signs of micro- and macro-vascular complications [3,4]. Second, individuals with prediabetes (Impaired Fasting Glucose [IFG] and/or impaired glucose tolerance [IGT]) have a high likelihood of developing DMT2 (10 to 20) times than of normoglycemic persons [5,6]

Worldwide, large randomized experimental studies such as the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study [7] and the US have demonstrated that [8] Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle intervention can effectively reduce the incidence of diabetes among those with prediabetes. Risk-scoring questionnaires may be useful to enhance individual risk assessment. Most risk-scoring models for DMT2 require specific blood test results [9-16], which presumes that a clinical encounter or diagnostic testing has already taken place. This limits widespread use of these models from a public health perspective. A diabetes risk assessment approach that relies on information a participant can selfcomplete without detailed knowledge of specific laboratory test values has been developed in Finland [17].

The Finnish Diabetes Risk Score [17] FINDRISC was adapted to include ethnicity and other key variables, such as gender and level of education to create the Canadian Diabetes Risk Assessment Questionnaire (CANRISK) [18], which has been widely used to identify those who are at risk of developing diabetes.

The countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), share a similar culture and ethnicity, while their sociodemographic distributions and socioeconomic development are also similar [19]. Although the countries of the GCC have experienced noticeable advances in delivering healthcare, the burden of non-communicable diseases is increasing rapidly [20] the prevalence of obesity in these countries, which is associated with multichronic diseases (i.e diabetes) exceeds that in the developed countries because of their rapid economic growth and associated changes in lifestyle [21-23]. Furthermore, the International Diabetes Federation reports that five of the countries of the GCC ranked globally among the top ten countries in the world for diabetes prevalence [24].

The main objective of this study was to describe the diabetes risk among participants in the capital of Saudi Arabia (Riyadh) using CANRISK.

Material and Methods

Recruitment and Participants: Participants for this study were recruited from local gathering social centers areas, i.e. Estarahes (party lounges), markets, malls and parks in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. All participants were healthy community-dwelling adults who gave their informed consent to participate and were residents of Riyadh with no history of diabetes. The study targeted males and females adults between the ages of 40 and 74 years of age in the period June-2012 to October-2012. Exclusion criteria for this study was previous diagnosis of Type I or II diabetes.

Study Design: In this cross-sectional study design, the CANRISK (CANadian RISK) evaluation tool was utilized to determine each participant’s risk for diabetes or pre-diabetes. The CANRISK questionnaire is a tool designed in 2009 to evaluate a person’s risk of developing type II diabetes or pre-diabetes. The CANRISK is an adaptation to the Canadian population from the FINDRISC (the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score) by including language to better evaluate the Canadian population, such as smoker vs. non-smoker, ethnic origin of the participants’ parents, any history of gestational diabetes in women and family history of diabetes. The CANRISK also includes questions regarding level of education and a selfevaluation of current health status in order to further evaluate the demographics of those evaluated (18). The CANRISK was administered by physical therapist research assistant or another health professional. As the original CANRISK tool is written in English, the data collectors were fluent in English, and participants were with good knowledge of English. Data collectors were trained and asked to revise the questionnaire with participants to insure the accurate knowledge and facilitate the accuracy of the information.

Outcomes: Variables of the questionnaire will be useful in drawing a picture of the risk of diabetes in the Saudi’s population. This study examined the following variables: body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, physical activity, daily consumption of fruits & vegetables, use of anti-hypertensive medication, history of high blood glucose, and family history of diabetes. The risk of developing DMT2 within 10 years is categorized as low, slightly elevated, moderate, high, and very high as per instructions the original validated tool.

Ethical consideration: Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee at King Saud University. The recruitment of potential participants was accomplished after explaining the objectives of the study by trained field research assistants. Participation was voluntary and consent was acquired from each participant. Confidentiality of all participants was maintained as no names were requested in the questionnaires.

Data Analysis: Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 20. Descriptive statistics were used for frequencies and percentage of the answers as well as for the mean and standard deviation of total score. The t-test for 2 independent samples was performed between male and female (gender) to explore significant differences between them on CANRISK total score categories.

Results

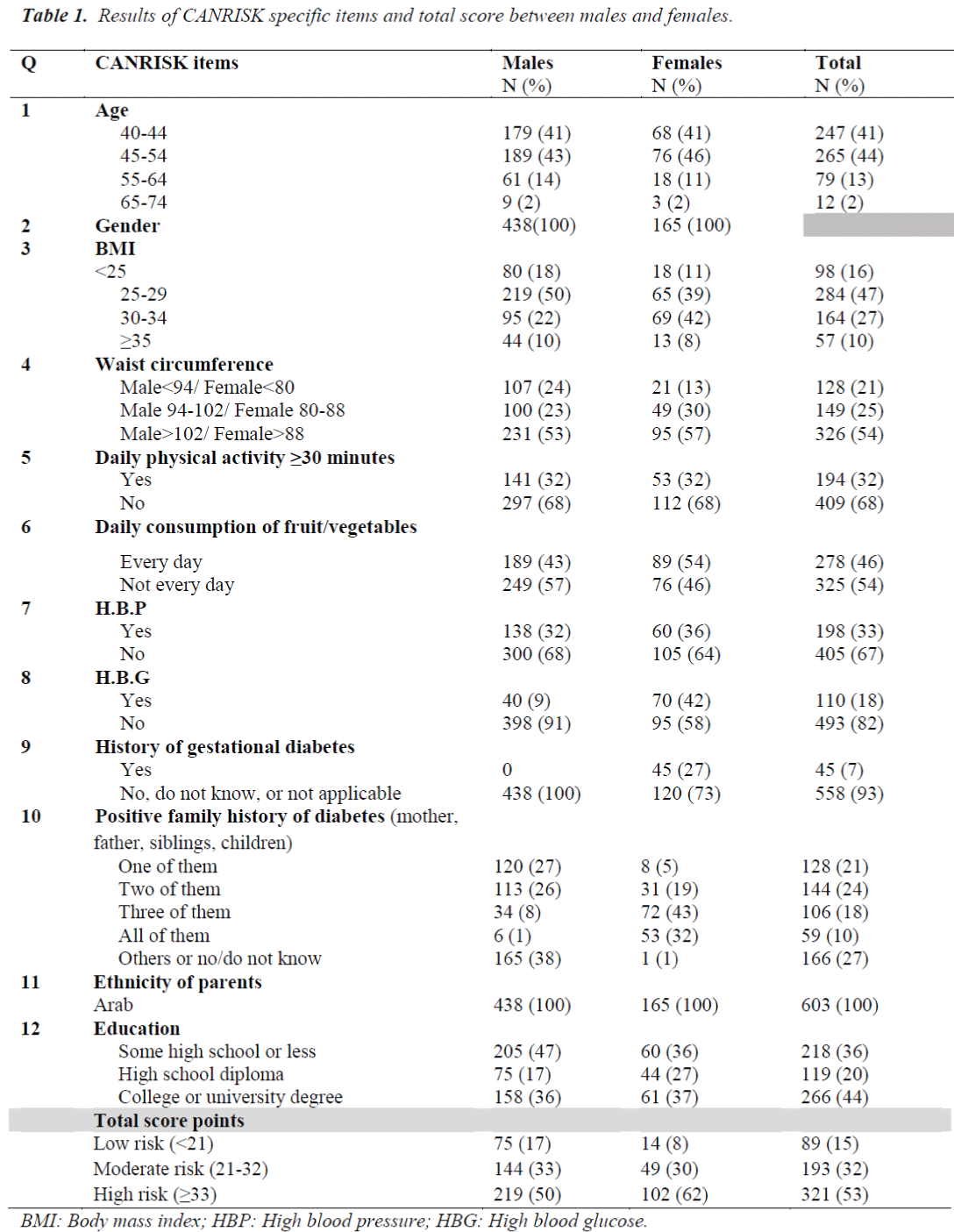

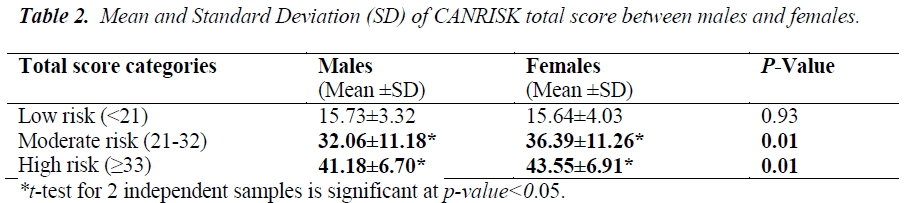

Six hundred and three (603) participants were recruited from public areas of Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, to participate in this study. The mean total CANRISK score for this study was 33.24 (SD=11.36) with a range from 9 to 68.With regards to the total scores for each participant of this study, more than half of them (53%)ranked in the category of high risk for developing diabetes (Table 1). By using the independent t-test, we found that women had significantly higher CANRISK total scores than did men in both moderate and high risk categories (Table 2), indicating that women had higher risk of developing DMT2 that did men. Level of P-value demonstrated statically relation (males and females) from one side and (moderate and high) total risk from the other side.

Participants

This study’s sample consisted of 73% males and 27% females. Table 1 presents a breakdown of the CANRISK results of specific items compared between males and females. While examining BMI, the mean BMI across all participants was 29.23 (SD=5.29) with a range of 15.37 to 57.33. Waist circumference was also examined using the tape measurement. More than half of participants; 53% of males and 58% of females, measured at the highest category of waist circumference indicating higher risk of developing diabetes.

According to the CANRISK questionnaire, women were questioned as to whether they had given birth to a large baby weighing 9 pounds. For those women answering in the affirmative, only 7% had developed gestational diabetes. With regards to ethnic groups, CANRISK divided ethnicity into 6 categories: White; Aboriginal; Black; East Asian; South Asian; and other non-white including Arab. However, all participants’ parents in this study were Arabic origins.

Educational levels for all participants were divided into “some high school or less” with 218 (36%) participants; “high school diploma” with 119 (20%) participants; “some college or university” and “university or college degree with 266 (44%) participants.

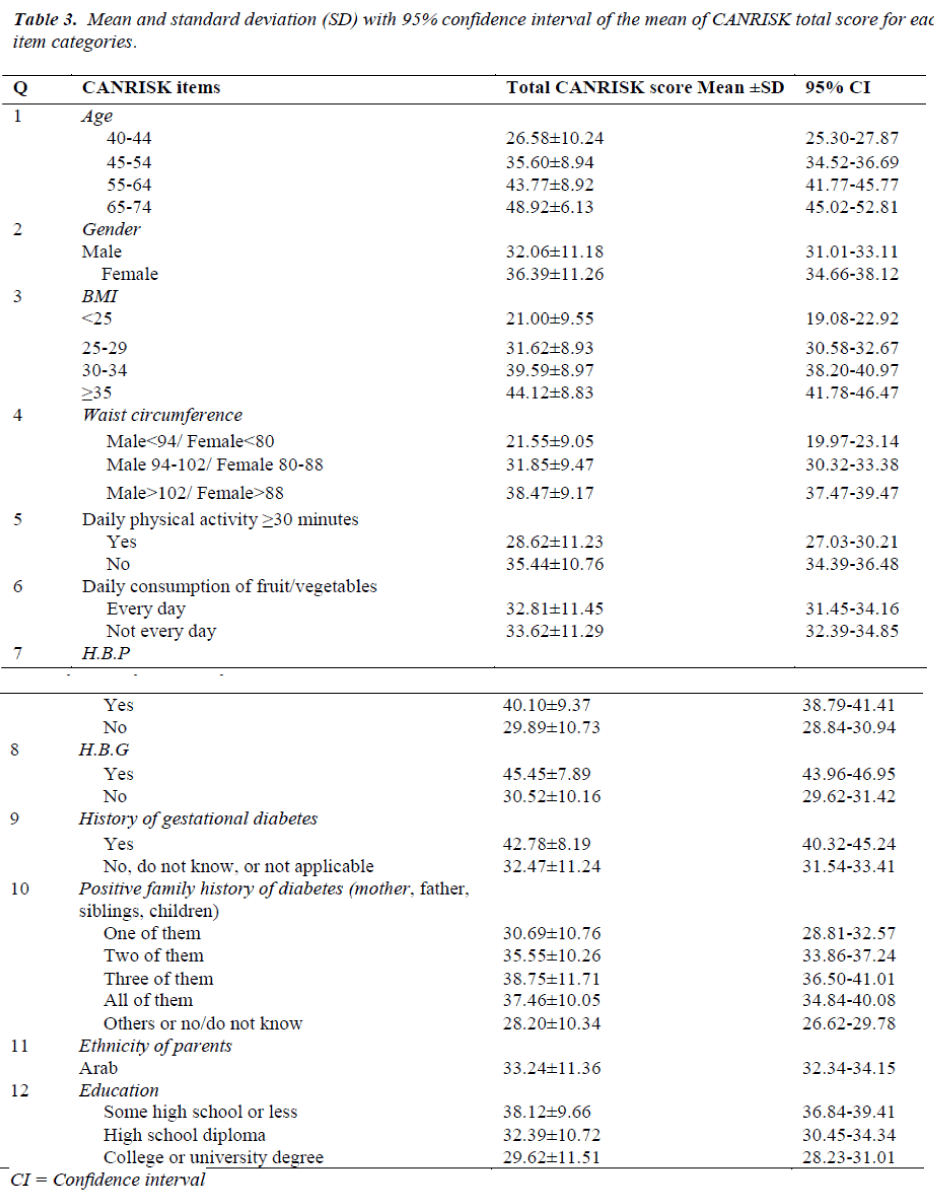

The mean, SD and 95% Confidence Interval for each item categories of CANRISK is presented in (Table 3). By looking at age, it is obvious that older participants scored higher in CANRISK total score for all age categories. Regarding BMI and waist circumference, participants with greater BMI and waist circumference had higher CANRISK total score. Similarly, participants who mentioned doing regular physical activity and consuming vegetable or fruit daily had smaller CANRISK total score. However, the difference in mean CANRISK score was not that high between participants who mentioned consuming vegetables or fruits daily and participants who did not. Additionally, participants who had history of high blood pressure, high blood sugar, and gestational diabetes scored higher in CANRISK total score. When asked about relatives with DM, participants who had more relatives with DM scored higher in CANRISK total score. Similarly, participants with university or college degree had smaller CANRISK total score than participants with high school diploma and participants with some high school or less education.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to describe the diabetes risk among participants in the capital of Saudi Arabia (Riyadh) using CANRISK. The outcomes of the CANRISK questionnaire were useful in drawing a picture of the risk of diabetes in the residents of Riyadh. Knowing the size of this problem in Saudi Arabia would be an important addition to the current literature around the world. Additionally, the current study contributes in drawing the attention of local policy makers for preventive strategies to decrease the incidence of getting diabetes. Moreover, the current results may encourage other Arab countries to evaluate such a risk in their populations.

This study searches for possible justification of high risk factors and to what extent it supports our study outcomes with regard to modifiable risk factors (such as BMI and a sedentary lifestyle). As it is accepted fact that the number of diabetic patients in Saudi Arabia is high and it is also increasing very rapidly due to lifestyle changes. In the CANRISK, most of the variables used to predict risk of DMT2 within 10 years are related to lifestyle. Therefore, it would be appropriate to apply CANRISK in spite of race/ethnicity or cultural differences.

Risk factors for type 2 diabetes

BMI

Our study represented that just below 50% of males and females participants are overweight with BMI score range [25-29] due to CANRISK. Such result supports the notion that risk of diabetes development is higher among participants with higher BMI. Indeed, there is strong evidence in literature with longitudinal studies showing that increased BMI is a strong risk factor for DMT2 [25,27]. A strong positive association between obesity and DMT2 is found both in men [26-28], and women [26,27,29].

Hypertension

CANRISK demonstrated that about third of males and females suffered from hypertension. previous studies showed that hypertension progression is an independent predictor of DMT2 [30-32]. Several possible factors are likely causes of the association between DMT2 and hypertension. Endothelial dysfunction could be one of the common pathophysiological pathways explaining the strong association between blood pressure and incident of DMT2. Clinical perspective indicate that markers of endothelial dysfunction are associated with new-onset of diabetes [33,34]. Insulin resistance could be another possible link between blood pressure levels and the incidence of DMT2 [35].

Central obesity and waist circumference

This study outcomes demonstrated that large waist circumference was prevalent among participants with more than 50% over 102 cm. Since the central obesity defined as the waist circumference >102 cm for males and >88 cm for females; our data revealed that approximately half of males and females suffered from central obesity. Evidence is now emerging that obesity-driven DMT2 might become the most common form of diabetes in adolescents within the next ten years [36].

Physical activity and dietary pattern

WHO and diabetes association’s world-wide developed Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. WHO stated that unhealthy diets and physical inactivity are among the leading causes of the major noncommunicable diseases, including cardiovascular disease, DMT2 and certain types of cancer, and contribute substantially to the global burden of disease, death and disability [37]. Regardless of this alarm from WHO since 2004, the study participants were not physically active, just above two third of men and women participants reported that they are not physically active. Also, nearly half of women and men participants reported not eating vegetables or fruits every day. However, the CANRISK does not take into account the type or frequency of physical activity as well as types of vegetables and fruits. Longitudinal studies revealed that physical inactivity is a strong risk factor for DMT2 [27,38-41]. Prolonged television watching as a surrogate marker of sedentary lifestyle, was reported to be positively associated with diabetes risk in both men and women [42-44].

In literature, moderate and vigorous physical activity is associated with a lower risk of DMT2 [38,45]. Evidence from clinical trials which included physical activity as an integral part of lifestyle interventions suggested that onset of DMT2 can be prevented or delayed as a result of successful lifestyle interventions that included physical activity [46]. Physical activity plays an important role in delaying or preventing the development of DMT2 in those at risk both directly by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing insulin resistance, and indirectly by beneficial changes in body mass and body composition [47-49].

An important life style factor associated with the development of DMT2 is dietary habits. Positive association has been reported between the risk of DMT2and different patterns of food intake [50]. Higher dietary glycemic index has been consistently associated with elevated risk of DMT2 in prospective cohort studies [51-53]. A prospective study found that regular consumption of white rice is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes whereas replacement of white rice by brown rice or other whole grains was associated with a lower risk [51]. A review which included 19 studies concluded that a higher intake of polyunsaturated fat and long- chain fatty acid is beneficial, whereas higher intake of saturated fat and trans fat adversely affects glucose metabolism and insulin resistance [54]. Another prospective study found higher consumption of butter, potatoes and whole milk to be associated with increased risk of DMT2. Higher consumption of fruits and vegetable was associated with reduced risk of DMT2 [55]. However, CANRISK is not looking in details about the type or frequency of food. Therefore, modification could be recommended when one admit CANRISK in future work.

Genetics

The current study reported that just under quarter of the participants have direct one or two relatives who have been diagnosed with diabetes, males percentage were higher than females with consideration to this point, this might be to large number of males compare to females in this study. Such outcomes of having 1,2, or more direct relatives would support the notion of increasing their risk in developing diabetes as several studies have found that genetic components plays an important role in pathogenesis of DMT2 [56-58]. Several prospective studies and cross sectional studies have reported that positive family history among first degree relatives gives an increased risk of DMT2 and the risk is greater when both parents are affected [56-60]. Also, diabetes prevalence varies substantially among different ethnic groups [61]. However, there was no diversity in ethnicity among Riyadh participants since our participants were all Arab and local.

Indeed, it is generally agreed that DMT2 is a poly etiological disorder. The genetic background, environmental factors, and the interaction between these all influence the development of the disease. This implies that of our sample had a genetic predisposition to develop DMT2, in addition to the high consanguinity rate among Saudi citizen [62].

Educational level

There is a considerable burden of DMT2 attribute to socioeconomic and lower educational levels in many countries [63] .Socioeconomic inequalities in health have been acknowledged in the scientific literature for more than 30 years [64] and a socioeconomic attribute for many diseases such as coronary heart disease and DMT2 [65]. The study finding demonstrated that lower level of education had a higher mean and confidence interval comparing to higher education. This may shed the light on the importance of this item in DMT2 risk assessment and ultimately in prevention.

Conclusion

DMT2 is a significant public health problem worldwide as well as in KSA. The current study provides insight into the progression and onset of DMT2 among Saudi nondiabetic population within next 10 years. Third of the study participants have high risk for developing DMT2 (one in three). Furthermore, females have higher risk to develop diabetes than males from CANRISK perspective. Therefore, there is a great need to address an effective obesity prevention program, taking into account the cultural context, to stop the wave of obesity and ultimately the wave of diabetes in KSA. Although the current results were based on a small sample size in the capital of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh data and experience can be generalized and used across regions in the kingdom and facilitate any implementation for any effective national plan addressing the cultural context in each region.

Limitations

The language of the CANRISK questionnaire is in English which prohibited us from giving the self-report questionnaire to the participants with no knowledge in English language. Also, one may suggest that a bigger sample with longer period in different areas across the kingdom matching with gender will draw a better picture about the estimated 10 years forecast in every single region (North, East, West, East) individually and across the country. Although the survey were randomly selected, a respondent bias may have possibly existed that could have skewed the results. Modification in physical activities and diet to ask more details about the frequencies will add valuable meaning for DMT2 risk prediction.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their appreciation to the College of Applied Medical Sciences Research Center and the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this research.

References

- Diabetes Atlas Fifth Edition. International Diabetes Federation [Internet]. Available from: http://www.idf.-org/diabetesatlas/5e/the-global-burden. [cited October 2012].

- Al-Nozha MM, Al-Maatouq MA, Al-Mazrou YY, Al- Harthi SS, Arafah MR, et al, Diabetes mellitus in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J 2004; 25(11): 1603-1610.

- Williams B.The Hypertension in Diabetes Study (HDS): a catalyst for change. Diabet Med. 2008 Aug;25 Suppl 2:13-9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464- 5491.2008.02506.

- Harris MI, Klein R, Welborn TA, Knuiman MW. Onset of NIDDM occurs at least 4-7 years before clinical di- agnosis. Diabetes Care 1992; 15(7): 815-819.

- Unwin N, Shaw J, Zimmet P, Alberti KG. Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glycaemia: the current status on definition and intervention. DiabetMed 2002; 19: 708-723.

- de Vegt F, Dekker JM, Jager A, Hienkens E, Kostense PJ, Stehouwer CD, et al; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study Group. Relation of impaired fasting and postload glucose with incident type 2 diabetes in a Dutch popu- lation: the Hoorn Study. JAMA 2001; 285(16): 2109-2113.

- Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1343-1350.

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Haman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al; The Diabetes Pre- vention Program Research Group. Reduction in the in- cidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393-403.

- Buijsse B, Simmons RK, Griffin SJ, Schulze MB. Risk assessment tools for identifying individuals at risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Epidemiol Rev 2011; 33:46-62.

- Griffin SJ, Little PS, Hales CN, Kinmonth AL, Ware- ham NJ. Diabetes risk score: towards earlier detection of type 2 diabetes in general practice. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2000; 16(3):164-171.

- He G, Sentell T, Schillinger D. A new public health tool for risk assessment of abnormal glucose levels. Prev Chronic Dis 2010; 7(2): 1-9.

- Heikes KE, Eddy DM, Arondekar B, Schlessinger L. Diabetes Risk Calculator: a simple tool for detecting undiagnosed diabetes and pre-diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008; 31: 1040-1045.

- Koopman RJ, Mainous AG, Everett CJ, Carter RE. Tool to assess likelihood of fasting glucose impairment(TAG-IT). Ann Fam Med 2008; 6(6): 555-561.

- Nelson KM, Boyko EJ; Third National Health and Nu- trition Examination Survey. Predicting impaired glu- cose tolerance using common clinical information: data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examina- tion Survey. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(7): 2058-2062.

- Park PJ, Griffin SJ, Sargeant L, Wareham NJ. The per- formance of a risk score in predicting undiagnosed hy- perglycemia. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 984-988.

- Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Vigo A, Pankow J, Ballan- tyne CM, Couper D, et al. Detection of undiagnoseddiabetes and other hyperglycemia states: the Atheroscl- erosis Risk in Communities Study. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(5): 1338-1343.

- Lindstrom J, Tuomilehto J. The Diabetes Risk Score: a practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care 2003; 26(3): 725-731.

- Kaczorowski J, Robinson C, Nerenberg K. Develop- ment of the CANRISK questionnaire to screen for pre- diabetes and undiagnosed type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabe- tes 2009; 33(4): 381-385.

- Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook. See https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html (last accessed 2 February 2011).

- Mandil A. Commentary: Mosaic Arab world, health and development. International Journal of Public Health 2009; 54: 361-362. [PubMed]

- Ng SW, Zaghloul S, Ali HI, et al. The prevalence and trends of overweight, obesity and nutrition-related non- communicable diseases in the Arabian Gulf States. Obes Rev 2011; 12: 1-13. [PubMed]

- Al-Nozha MM, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Maatouq MA, et al. Obesity in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J2005; 26: 824- 829. [PubMed]

- Mabry RM, Reeves MM, Eakin EG, et al. Evidence of physical activity participation among men and women in the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council: a review. Obes Rev 2010;11:457–64.[PubMed].

- Diabetes Atlas Fifth Edition. International Diabetes Federation [Internet]. Available from: http://www.idf.-org/diabetesatlas/5e/Update2012 [cited 2012].

- Meisinger C, Thorand B, Schneider A, Stieber J, Dor- ing A, Lowel H. Sex differences in risk factors for inci- dent type 2 diabetes mellitus: the MONICA Augsburg cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(1): 82-89.

- Knowler WC, Pettitt DJ, Saad MF, Charles MA, Nel- son RG, Howard BV, et al. Obesity in the Pima Indi- ans: its magnitude and relationship with diabetes. A J Clin Nutr 1991; 53: 1543S-1551S.

- Almdal T, Scharling H, Jensen JS, Vestergaard H. Higher prevalence of risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus and subsequent higher incidence in men. Eur J Intern Med 2008 ; 19(1): 40-45.

- Skarfors ET, Selinus KI, Lithell HO. Risk factors for developing non-insulin dependent diabetes: a 10 year follow up of men in Uppsala. BMJ 1991; 303(6805): 755-760.

- Colditz GA, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Hennekens CH, Arky RA, et al. Weight as a risk factor for clinical diabetes in women. Am J Epidemiol 1990: 132(3): 501-513.

- Kumari M, Head J, Marmot M. Prospective study of social and other risk factors for incidence of type 2 dia- betes in the Whitehall II study. Arch Intern Med 2004; 64 (17): 873-880.

- Conen D, Ridker PM, Mora S, Buring JE, Glynn RJ. Blood pressure and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Women's Health Study. Eur Heart J 2007;28(23):2937-43.

- Movahed MR, Sattur S, Hashemzadeh M. Independent association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and hyper- tension over a period of 10 years in a large inpatient population. ClinExpHypertens 2010;32 (3):198-201.

- Meigs JB, Hu FB, Rifai N, Manson JE. Biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and risk of type 2 diabetes mel- litus. JAMA 2004;291(16):1978-86.

- Meigs JB, O’Donnel CJ, Tofler GH, Benjamin EJ, Fox CS, Lipinska I, et al. Hemostatic markers of endothelial dysfunction and risk of incident type 2 diabetes: TheFramingham Offspring Study. Diabetes 2006; 55(2):530-7.

- Ferrannini E, Buzzigoli G, Bonadonna R, Giorico MA, Oleggini M, Graziadei L, et al. Insulin resistance in es- sential hypertension. N Engl J Med 1987;317(6):350-7.

- Rees, A., Thomas, N., Brophy, S., Knox, G., & Wil- liams, R. Cross sectional study of childhood obesity and prevalence of risk factors for cardiovascular dis- ease and diabetes in children aged 11–13. BMC Public Health2009;9:86-91.

- Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health.The Fifty-seventh World Health Assembly (2004). WHA57.17. [Online] Available:www.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA57/A57_R17- en.pdf

- Fretts AM, Howard BV, Kriska AM, Smith NL, Lumley T, Lee ET, et al. Physical activity and incident diabetes in American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. A J Epidemiol 2009;170(5):632-9.

- Gimeno D, Elovainio M, Jokela M, De VR, Marmot MG, Kivimaki M. Association between passive jobs and low levels of leisure-time physical activity: the Whitehall II cohort study. Occup Environ Med 2009;66(11):772-6.

- Villegas R, Shu XO, Li H, Yang G, Matthews CE, Leitzmann M, et al. Physical activity and the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the Shanghai women's health study. Int J Epidemol 2006;35(6):1553-62.

- Jeon CY, Lokken RP, Hu FB, van Dam RM. Physical activity of moderate intensity and risk of type 2 diabe-tes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2007;30(3):744-52.

- Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitusin women. JAMA 2003;289(14):1785-91.

- Hu FB, Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Physical activity and television watching in relation to risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in men. Arch Intern Med 2001;161(12):1542-8.

- Krishnan S, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR. Physical activity and television watching in relation to risk of type 2 dia- betes: the Black Women's Health Study. Am J Epide- miol 2009;169(4):428-34.

- Weinstein AR, Sesso HD, Lee IM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, et al. Relationship of Physical Activity vs Body Mass Index With Type 2 Diabetes in Women. JAMA 2004 Sep 8;292(10):1188-94.

- Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, Wang JX, Yang WY, An ZX,et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 1997; 20 (4):537-44.

- Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, Lachin JM, Bray GA, Delahanty L, et al. Effect of weight loss with life- style intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006; 29(9):2102-7.

- Boule NG, Haddad E, Kenny GP, Wells GA, Sigal RJ. Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of con- trolled clinical trials. JAMA 2001; 286(10):1218-27.

- Kay SJ, Fiatarone Singh MA. The influence of physical activity on abdominal fat: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev 2006;7(2):183-200.

- Liese AD, Weis KE, Schulz M, Tooze JA. Food intake patterns associated with incident type 2 diabetes: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes Care 2009; 32(2):263-8.

- Sun Q, Spiegelman D, van Dam RM, Holmes MD, Malik VS .Willett WC, et al, White rice, , brown rice,and risk of type 2 diabetes in US men and women. Arch Intern Med 2010;170(11):961-9.

- Schulze MB, Liu S, Rimm EB, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and die- tary fiber intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes inyounger and middle-aged women. Am J ClinNutr 2004;80(2):348-56.

- Villegas R, Liu S, Gao YT, Yang G, Li H, Zheng W, et al. Prospective study of dietary carbohydrates, glyce- mic index, glycemic load, and incidence of type 2 dia- betes mellitus in middle-aged Chinese women. Arch In- tern Med 2007;167(21) :2310-6.

- Hu FB, van Dam RM, Liu S. Diet and risk of Type II diabetes: the role of types of fat and carbohydrate. Dia- betologia 2001;44(7):805-17.

- Montonen J, Knekt P, Harkanen T, Jarvinen R, Heliovaara M, Aromaa A, et al. Dietary patterns and the incidence of type 2 diabetes. AmJEpidemiol 2005;161(3) :219-27.

- Amini M and Janghorban M Diabetes and impaired glucose regulation in first- degree relatives of patients with type 2 diabetes in Isfahan, Iran: Prevalence and risk factors. Rev DiabetStud 2007; 4:169-176.

- Meigs JB, Cupples LA, Wilson PW. Parental transmis- sion of type 2 diabetes: the Framingham OffspringStudy. Diabetes 2000; 49(12):2201-7.

- Harrison TA, Hindorff LA, Kim H, Wines RC, Bowen DJ, McGrath BB, et al. Family history of diabetes as a potential public health tool. Am J Prev Med 2003; 24(2):152-9.

- Ma XJ, Jia WP, Hu C, Zhou J, Lu HJ, Zhang R, et al.Genetic characteristics of familial type 2 diabetes pedi- grees: a preliminary analysis of 4468 persons from 715 pedigrees. CMJ 2008; 88(36):2541-3.

- Bjornholt JV, Erikssen G, Liestol K, Jervell J, Thaulow E, Erikssen J. Type 2 diabetes and maternal family his- tory: an impact beyond slow glucose removal rate andfasting hyperglycemia in low-risk individuals? Results from 22.5 years of follow-up of healthy nondiabetic men. Diabetes Care 2000;23(9):1255-9.

- Diamond J. The double puzzle of diabetes. Nature 2003; 423(6940):599-602.

- Elhadd, T. A., Al-Amoudi, A. A., Alzahrani, A. S. Epi- demiology, clinical and complications profile of diabe- tes in Saudi Arabia: A review. Annals of Saudi Medi- cine 2007;27:241-250.

- Mackenbach JP, Bakker MJ: Tackling socioeconomic inequalities in health: analysis of European experi-ences. Lancet 2003, 362(9393):1409-14.

- Mackenbach JP: Socioeconomic inequalities in health in The Netherlands: impact of a five year research pro- gramme.BMJ 1994, 309(6967):1487-91.

- Agardh E, Allebeck P, Hallqvist J, Moradi T, Sidor- chuk A: Type 2 diabetes incidence and socioeconomic position: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inter- national Journal of Epidemiology 2011, 1-15.