Review Article - Journal of Physical Therapy and Sports Medicine (2018) Volume 2, Issue 1

Compared to TKA or HTO, will you choose UKA to treat medial compartmental knee osteoarthritis? A review paper on UKA.

- *Corresponding Author:

- Feng-Lai Yuan

Department of Orthopaedics, The Third Hospital Affiliated to Nantong University, Wuxi, Jiangsu 214041, China

Tel: +86-510-82603332

E-mail: bjjq88@163.com

Accepted date: February 06, 2018

Citation: Ye JX, Yang XF, Lian-Sheng D, et al. Compared to TKA or HTO, will you choose UKA to treat medial compartmental knee osteoarthritis? A review paper on UKA. J Phys Ther Sports Med 2018;2(1):34-40.

DOI: 10.35841/physical-therapy.2.1.26-32

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Physical Therapy and Sports MedicineAbstract

Over the past many years, unicompartment knee arthroplasty (UKA) had been used to treat unicompartment osteoarthritis (OA) of knee. In spite of many years of experiences in performing UKA, the orthopedics scholars had not reached an agreement on it. Herein, compared to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and high tibial osteotomy (HTO), we reviewed the controversy on the advantages and disadvantages about the usage of UKA and the indications, methods, and complications of revision of UKA. Finally, we concluded that compared to TKA or HTO, UKA might be a very good choice for us in the treatment of medial compartment knee OA.

Keywords

Arthroplasty, Knee, Osteoarthritis, Unicompartment.

Introduction

Unicompartment knee arthroplasty (UKA) is an effective treatment for medial compartmental osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee. UKA has been shown to be a satisfactory curable choice for this type of OA and its advantages over TKA are well known: retention of soft tissue and bone stock, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) preservation, earlier and easier rehabilitation, better functional result and lower need for blood transfusion in the immediate postoperative period [1,2]. HTO is also an effective treatment method for unicompartment knee OA of the knee. It also had some advantages and disadvantages. HTO and UKA are reconstructive surgeries advocated for patients with unicomparemental knee OA that many delay or perhaps avoid the need for TKA [3].

All these advantages led to an exponential increase in the number of UKAs performed globally, and in turn, to an increase in the number of revision rates in recent years. The high rate of complications related to the earliest UKAs reduced its popularity in the 1990s [2]. Even with early disagreement results, recent evidence showed inspiring results and survival of modern implants [4,5]. In the course of time, a steady progress of implants, both in the light of manufacturing and design, more cautious patient selection, and developments in surgical approaches have led to survival rates similar to those of TKA [1]. Medial UKA performed in England and Wales represents seven to 11% of all knee arthroplasty procedures, and now that number is also on the rise [6]. Therefore, an increasing number of surgeons focus on UKA due to its better results compared with early research. Compared to TKA or HTO, UKA may also be having some positive and negative factors. This article summarizes the progression of UKA in recent years. And it has been approved by the ethical committee of the third hospital affiliated to Nantong University.

The survival rate of UKA in recently

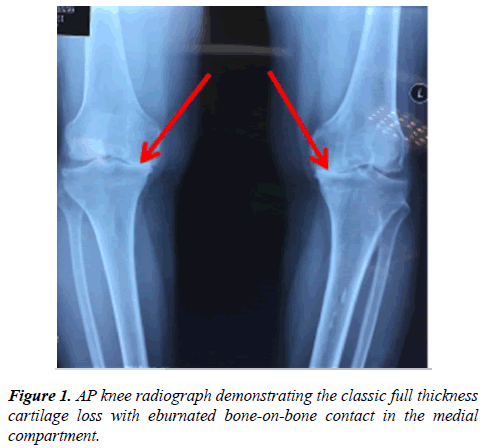

There is almost no dispute about the indication of the UKA operation now. Cartilage wear was found to take place in the anteromedial part of the tibial plateau of knee, with preservation of the posterior cartilage. This was called anteromedial knee OA (AMOA). Key radiographic features on the anteroposterior (AP) X- ray are: Full thickness cartilage loss with eburnated bone-on-bone contact in the medial compartment (Figure 1). Failure to demonstrate full thickness loss is a well-established contra-indication to UKA, with results recognized as being poorer in the medium term. This is an important aspect of the UKA survival rate.

In some reports, survivorship did not satisfaction markedly, although there was a trend towards UKA beyond twelve years. Some editors showed worse survivorship compared to TKA, with survival rates almost five years after implantation as low as 84.7% [7,8]. In 2013, Bruni et al. reported a survivorship at eight years approximates 83% [9], and in 2016, the same group published another report which described a survivorship about 87.6% [10]. A study on the St. Georg Sled showed almost 85.9% survivals at eighteen- twenty years with a mean age at operation of sixty-seven years [11]. In a study by Elke et al., the five- year implant survival rate was about 87.8% [12].

Recently, other reports showed better outcomes. Forster et al. reported a survival rate approximate 97.9% at two years, 94.1% at five years, and 91.3% at ten years [6]. Their followup rate about 97.1%, that is similar to other studies of this characteristic [13,14]. Some studies reviewed the recent investigations of modular UKA designs and found survivorship rates of 93% to 96% at seven to ten years [15,16]. Pennington et al. reported on patients younger than sixty years with 92% survival rates at ten years with Miller-Galante implants [17]. Pandit et al. reported a ten-year survival rate about ninety-six %, if all implant-related reoperations were considered failures; the incidence of implant-related reoperations was almost 2.9% during a mean follow-up period about 5.6 years [18]. Some authors concluded that UKA results were associated with survival rates about 90%-98% at ten years [13,19]; and Price et al. published long-term results with twenty-year survivorship rates of greater of 90% [19]. Lateral and medial UKAs showed similar survival rates based on recent studies [14,20].

Comparison of UKA and TKA

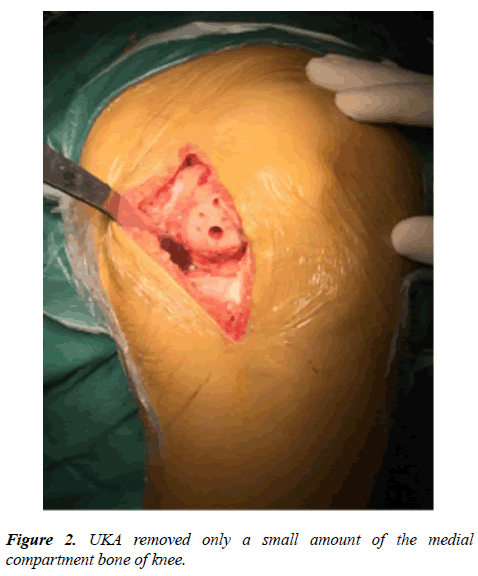

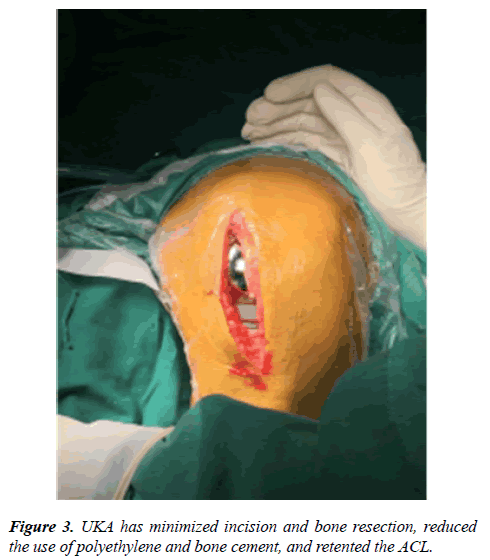

UKA, which is limited to a single compartment, can remove the cartilage lesion of the knee joint only in patients with unicompartment OA; thus, it has the advantages of minimizing bone resection, reducing the use of polyethylene and bone cement, and preserving more normal knee function in comparison with TKA, thereby resulting in a shorter operative time and faster recovery (Figure 2). Hence, postoperative morbidity period is short and good joint motion can be achieved [21]. Many reported advantages of UKA over TKA include conservation of bone stock, an easier and shorter recovery period, lower overall cost, lower morbidity, better functional result due to more normal knee kinematics, and a subjective feeling of a more natural knee [22,23] (Figure 3).

In the present study, Foran et al. demonstrated that there were no significant differences in five-year survival rates between UKA and TKA knees [13]. Liddle et al. reported that the clinical results after TKA and UKA are good; however, functional results and return to sports appear to favor UKA. The main disadvantage of UKA is the lower survival rate in the second decade [24]. Matthew et al. thought that while patients with UKA had higher pre- and postoperative scores than patients with TKA, the differences in scores were similar in both groups and survival appeared higher in patients with TKA [25].

However, these studies are not supported by usable implant registry data from Gro et al., who found that survival rate of UKAs remains enormously lower than that of TKAs, despite a survival benefit for TKA over UKA. The decision to perform UKA should be made with a distinct awareness that its survival is substantially inferior to that of TKA, and that any perceived advantages of UKA should be balanced against this issue of decreased durability [26]. Tuukka et al. also believed that UKA offered tempting advantages compared with TKA; however, the revision frequency for UKAs in widespread use, as measured in a large national registry, was poorer than that of TKAs [27].

There has also been debate about the issue of age at operation for UKA versus TKA. Homayoun et al. believed that, due to its less invasive nature, patients older than seventy-five years undergoing UKA demonstrated a faster initial recovery compared to TKA, while maintaining comparable complications and midterm survival rates [28]. However, its use was criticized because of its potential higher revision rate compared to TKA [25,29]. Overall patient satisfaction scores were significantly higher for UKA than TKA in patients younger than fifty-five years of age. This relationship is less pronounced for patients older than sixty-five years [30].

The perioperative complication rate of UKA in the Homayoun et al. study was low; and more importantly, the revision rates were low and comparable to that of TKA [28]. In the Liddle et al. report, UKA was associated with a lower risk of perioperative complications, such as venous thromboembolic events, stroke and myocardial infarction, and blood transfusion rate [24]. In a meta-analysis by Alisara et al., the authors concluded that postoperative complications in the TKA group were higher compared to the UKA group, whereas revision rates were higher in the UKA group compared to the TKA group [31]. Two previous studies reported a lower rate of venous thrombosis for UKA compared with TKA [22,32]. Leta et al. reported that approximate 3.4% of primary UKAs and about 24% of primary TKAs were revised due to infection [33]. A much larger study reviewing UKA and TKA over a five year period found no statistical significance for thromboembolic events between the 2 subgroups [34].

Comparison of UKA and HTO

The surgical curable methods for OA of the knee largely include HTO and UKA [35]. The differences in indication and clinical prognoses of these two surgical approaches are still debated.

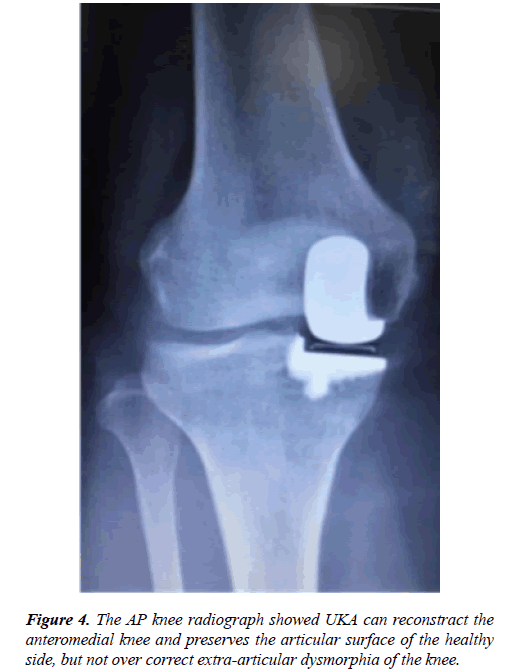

In comparison with HTO, UKA is a reconstructive surgery that replaces the worn out articular surface with an artificial structure, and preserves the articular surface of the healthy side (Figure 4). Additionally, weight-bearing ambulation and early rehabilitation are possible within a short period of time with the advantage of fewer postoperative complications [36]. UKA is known to have advantages of faster return to activities of daily living and early recovery from pain. HTO has a good prognosis, for which malalignment of the medial compartment of the knee OA had been corrected [37]. However, it is technically difficult to achieve an ideal valgus knee after surgery. Also, occurrence of complications after HTO is higher than after UKA.

Broughton et al. retrospectively investigated UKA and lateral closing wedge HTO in their follow-up observations for a five year period. They reported satisfactory results of 76% for patients undergoing UKA and 43% of those undergoing HTO [38]. Sukenborg-Colsman et al. prospectively compared prognoses of UKA and HTO for seven to ten years and reported a better prognosis and fewer operative complications for UKA [36]. The early clinical results of UKA at six months were significantly better compared with HTO [37]. A recent meta-analysis comparing HTO versus UKA indicated that UKA is a more favorable technique for improving clinical results and relieving pain up to ten years postoperatively [39].

Furthermore, with respect to degenerative changes of the knee joint, a report that a degenerative change of the lateral tibiofemoral compartment has not shown a significant difference between HTO and UKA groups, despite having achieved a greater valgus alignment by HTO [40].

Conclusively, either HTO or UKA is a rather outstanding surgical treatment as long as appropriate patient selection can be made. Otto et al. concluded that despite a previous UKA and HTO having a negative effect on a subsequent TKA, the effect is relatively small for HTOs considering the potential benefit of delaying the eventual TKA, and the fact that most patients with HTO and UKA never undergo revision surgery. Therefore, they argued that their findings supported the continued use of UKA and HTO in selected patients. However, it is critical that patients undergoing those reconstructive procedures be counseled about the risks and complexities associated with revision of these procedures to TKAs [41]. Postoperative rate of revision and complications did not differ significantly between two groups. With the correct patient selection, both HTO and UKA show effective and reliable results [42].

Revision of UKA and its methods

In early reports, UKA had worse results than TKA and UKA had higher revision rates. There were many reasons for revision, including technical failure, aseptic loosening, and unexplained pain among others. Lindstrand et al. discussed revisions due to loosening, subsidence, or fracture. These revisions were performed within one year [43]. In a series by Jong et al., time to reoperation was approximately 22.3 months [44]. Estrella et al. reported a revision rate of failed UKAs of 3.4% [45], and lower than in other recent series [46], of more than 6%.

Unexplained pain was an important indication for revision. When performing revision surgery in patients with pain of unknown etiology, the results were poorer than when the etiology was known. Revisions for unexplained knee pain may be partly responsible for the increased incidence of revisions during UKA compared to TKA [47].

From a technical perspective, the loss of anatomic references and bone stock makes UKA revision surgery difficult, and according to some authors, as technically challenging as TKA revision [48,49]. The main technical challenges in revision surgery of UKA are bone stock loss and difficulty in the location and position of the joint line and axis due to altered anatomical landmarks [45].

Another possible explanation of the higher revision rate of UKA is the long learning curve. Jones et al. discussed biased operative procedures on revision surgery. For example, excessive tibial resection implies more bone loss and altered anatomic landmarks [49]. Robertson et al. concluded that there is an association between the numbers of UKAs performed in a surgical unit and the incidence of subsequent revisions [50]. Rees et al. showed that the average American Knee Society Score of the first ten cases was significantly lower than that of subsequent ones [51]. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (2004) reported that surgeons with fewer than twenty three cases per year produce significantly lower survival rates [49]. Zambianchi et al. concluded that prosthetic design and model had less of an impact on results than surgeon experience [16]. Perkins and Gunckle, in a study with a six-year follow-up period, reported that the possibility of requiring revision surgery was high when the postoperative tibiofemoral angle was larger than 3° varus or larger than 7° valgus [52].

Apart from well known risk factors, Jeschke et al. recently reported a significant influence of age, sex, obesity, fixation, depression, and complicated diabetes on the UKA revision rate. They argued that surgical indications and preoperative patient counseling should be considered [11]. While improvements in implant design and surgical technique have led to reduced revision rates, patient selection seems to be crucial for success in UKA. Barrett and Scott suggested that errors in patient selection were responsible for about 31% failure rate [53]; Saldanha et al. also noted that almost 13% failures cases were due to poor patient selection [1].

The methods of UKA revision include UKA and TKA. Revision of a UKA with another UKA is not routinely recommended. Pearse et al. in reviewing the New Zealand Joint Registry showed that UKA revision with a new UKA had a revision rate about 6.67% in the first year, compared to 0.48% in primary TKA and 1.97% in UKA revision with TKA [54]. Hang et al. [55] obtained similar conclusions.

Some surgeons claim that revision of a primary UKA to TKA yields the same results as a primary TKA [56]. However, many surgeons prefer to offer UKA to younger patients and to postpone TKA, believing that the outcomes of UKA to TKA are equal to those of primary TKA and better than those of TKA to TKA [1,54]. Tesfaye et al. compared primary UKAs and primary TKAs revised to TKAs. Overall, about 12% of those in the UKA to TKA group and 13% in the TKA to TKA group underwent re-revision [33]. The ten-year survival rates of UKA to TKA versus TKA to TKA were approximate 82% versus 81%, respectively. However, the risk of re-revision was two times higher for TKA to TKA patients who were older than seventy years of age at the time of revision. TKA to TKA had a longer operative time and more of the procedures required stems and stabilization compared with UKA to TKA. TKA to TKA had a higher percentage of re-revisions due to deep infection compared with UKA to TKA.

Complications

UKA is an effective curable for patients with OA of the knee, and may be a good alternative to TKA in certain cases. However, UKA also has shortcomings, such as difficulties in surgical technique, subluxation of the tibiofemoral joint due to inaccurate location, migration of prosthesis, infection, and bone defects developed during revision. Despite the above mentioned technical difficulties, complications of UKA have rarely been reported [57]. But Jong et al. recently reported intra- and postoperative complications of UKA. Intraoperative complications included fractures of the medial tibial condyle, the intercondylar eminence, and rupture of the medial collateral ligament (MCL). Postoperative complications included: 1) polyethylene bearing dislocation, 2) suprapatellar bursitis, 3) aseptic loosening of the femoral component, 4) soft tissue impingement due to malalignment, 5) TKA conversion due to medial component overhanging, 6) periprosthetic fracture, and 7) pain of unexplained etiology, among others [29].

Still many published mechanisms of UKA failure [58,59] included aseptic loosening, arthritic progression, and unexplained knee pain. The most frequent causes of UKA failure are OA progression in other knee compartments and aseptic loosening of components [60]. Berger et al. reported that the indication of UKA revision to TKA, at seven and eleven years, was due to progression of patellofemoral arthritis. At the final follow-up visit, no radiographically loose component was found and there was no evidence of periprosthetic osteolysis [61]. In recent reports, the most frequent complications as a reason for revision was progression of OA [6]. Aseptic loosening was the second most common complication, which occurred most commonly on the tibial side. Aseptic loosening after UKA has been described as responsible for up to 67% of all failures [55].

In general, compared to TKA or HTO, UKA not only have many advantages, but also have many disadvantages in itself. Only if we choose right patents, have a strict indication of the operation, regular surgical procedure, and good perioperative management, UKA might give us a good result in the curable of medial compartmental knee OA.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (81270011; 81472125) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant BK20151114), Foundation of Traditional Chinese Medicine of Jiangsu Province (YB201578) and Medical Innovation Center Team of Health and Family Planning Commission of Wuxi, No. CXTD006.

References

- Saldanha KA, Keys GW, Svard UC, et al. Revision of Oxford medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty to total knee arthroplasty - results of a multicentre study. Knee. 2007;14: 275-9.

- Chou DT, Swamy GN, Lewis JR, et al. Revision of failed unicompartmental knee replacement to total knee replacement. Knee. 2012;19: 356-9.

- Robertsson O, Wdahl A. The Risk of Revision After TKA Is Affected by Previous HTO or UKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473: 90-93.

- Kwong LM, Nielsen ES, Ruiz DR, et al. Cementless total knee replacement fixation: a contemporary durable solution--affirms. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B: 87-92.

- Nakama GY, Peccin MS, Almeida GJ, et al. Cemented, cementless or hybrid fixation options in total knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis and other non-traumatic diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10: CD006193.

- Forster-Horvath C, Artz N, Hassaballa MA, et al. Survivorship and clinical outcome of the minimally invasive Uniglide medial fixed bearing, all-polyethylene tibia, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty at a mean follow-up of 7.3years. Knee. 2016;23: 981-86.

- Kuipers BM, Kollen BJ, Bots PC, et al. Factors associated with reduced early survival in the Oxford phase III medial unicompartment knee replacement. Knee. 2010;17: 48-52.

- Price AJ, Waite JC, Svard U. Long-term clinical results of the medial Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005: 171-80.

- Bruni D, Akkawi I, Iacono F, et al. Minimum thickness of all-poly tibial component unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in patients younger than 60 years does not increase revision rate for aseptic loosening. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21: 2462-7.

- Bruni D, Gagliardi M, Akkawi I, et al. Good survivorship of all-polyethylene tibial component UKA at long-term follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24: 182-7.

- Steele RG, Hutabarat S, Evans RL, et al. Survivorship of the St Georg Sled medial unicompartmental knee replacement beyond ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88: 1164-8.

- Jeschke E, Gehrke T, Gunster C, et al. Five-Year Survival of 20,946 Unicondylar Knee Replacements and Patient Risk Factors for Failure: An Analysis of German Insurance Data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98: 1691-98.

- Foran JR, Brown NM, Della Valle CJ, et al. Long-term survivorship and failure modes of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471: 102-8.

- Smith JR, Robinson JR, Porteous AJ, et al. Fixed bearing lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty--short to midterm survivorship and knee scores for 101 prostheses. Knee. 2014;21: 843-7.

- Scott CE, Eaton MJ, Nutton RW, et al. Proximal tibial strain in medial unicompartmental knee replacements: A biomechanical study of implant design. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B: 1339-47.

- Zambianchi F, Digennaro V, Giorgini A, et al. Surgeon's experience influences UKA survivorship: a comparative study between all-poly and metal back designs. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23: 2074-80.

- Pennington DW, Swienckowski JJ, Lutes WB, et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in patients sixty years of age or younger. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A: 1968-73.

- Pandit H, Jenkins C, Gill HS, et al. Minimally invasive Oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee replacement: results of 1000 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93: 198-204.

- Berger RA, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ, et al. Results of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty at a minimum of ten years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87: 999-1006.

- Ollivier M, Abdel MP, Parratte S, et al. Lateral unicondylar knee arthroplasty (UKA): contemporary indications, surgical technique, and results. Int Orthop. 2014;38: 449-55.

- Chassin EP, Mikosz RP, Andriacchi TP, et al. Functional analysis of cemented medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11: 553-9.

- Sun PF, Jia YH. Mobile bearing UKA compared to fixed bearing TKA: a randomized prospective study. Knee. 2012;19: 103-6.

- Bolognesi MP, Greiner MA, Attarian DE, et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty among Medicare beneficiaries, 2000 to 2009. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95: e174.

- Liddle AD, Judge A, Pandit H, et al. Adverse outcomes after total and unicompartmental knee replacement in 101,330 matched patients: a study of data from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Lancet. 2014;384: 1437-45.

- Lyons MC, MacDonald SJ, Somerville LE, et al. Unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty database analysis: is there a winner? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470: 84-90.

- Dyrhovden GS, Lygre SH, Badawy M, et al. Have the Causes of Revision for Total and Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasties Changed During the Past Two Decades? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017.

- Niinimaki T, Eskelinen A, Makela K, et al. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty survivorship is lower than TKA survivorship: a 27-year Finnish registry study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472: 1496-501.

- Siman H, Kamath AF, Carrillo N, et al. Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty vs Total Knee Arthroplasty for Medial Compartment Arthritis in Patients Older Than 75 Years: Comparable Reoperation, Revision, and Complication Rates. J Arthroplasty. 2017.

- Labek G, Thaler M, Janda W, et al. Revision rates after total joint replacement: cumulative results from worldwide joint register datasets. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93: 293-7.

- Von Keudell A, Sodha S, Collins J, et al. Patient satisfaction after primary total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: an age-dependent analysis. Knee. 2014;21: 180-4.

- Arirachakaran A, Choowit P, Putananon C, et al. Is unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) superior to total knee arthroplasty (TKA)? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25: 799-806.

- Willis-Owen CA, Sarraf KM, Martin AE, et al. Are current thrombo-embolic prophylaxis guidelines applicable to unicompartmental knee replacement? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93: 1617-20.

- Leta TH, Lygre SH, Skredderstuen A, et al. Outcomes of Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty After Aseptic Revision to Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Comparative Study of 768 TKAs and 578 UKAs Revised to TKAs from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (1994 to 2011). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98: 431-40.

- Brown NM, Sheth NP, Davis K, et al. Total knee arthroplasty has higher postoperative morbidity than unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a multicenter analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27: 86-90.

- Weale AE, Lee AS, MacEachern AG. High tibial osteotomy using a dynamic axial external fixator. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001: 154-67.

- Stukenborg-Colsman C, Wirth CJ, Lazovic D, et al. High tibial osteotomy versus unicompartmental joint replacement in unicompartmental knee joint osteoarthritis: 7-10-year follow-up prospective randomised study. Knee. 2001;8: 187-94.

- Jeon YS, Ahn CH, Kim MK. Comparison of HTO with articular cartilage surgery and UKA in unicompartmental OA. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2017;25: 2309499016684092.

- Broughton NS, Newman JH, Baily RA. Unicompartmental replacement and high tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis of the knee. A comparative study after 5-10 years' follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68: 447-52.

- Spahn G, Hofmann GO, von Engelhardt LV, et al. The impact of a high tibial valgus osteotomy and unicondylar medial arthroplasty on the treatment for knee osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21: 96-112.

- Yim JH, Song EK, Seo HY, et al. Comparison of high tibial osteotomy and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty at a minimum follow-up of 3 years. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28: 243-7.

- Robertsson O, A WD. The risk of revision after TKA is affected by previous HTO or UKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473: 90-3.

- Fu D, Li G, Chen K, et al. Comparison of high tibial osteotomy and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in the treatment of unicompartmental osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28: 759-65.

- Lindstrand A, Stenstrom A, Ryd L, et al. The introduction period of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty is critical: a clinical, clinical multicentered, and radiostereometric study of 251 Duracon unicompartmental knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15: 608-16.

- Ji JH, Park SE, Song IS, et al. Complications of medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2014;6: 365-72.

- Borrego Paredes E, Barrena Sanchez P, Serrano Toledano D, et al. Total Knee Arthroplasty After Failed Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty. Clinical Results, Radiologic Findings, and Technical Tips. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32: 193-96.

- Oduwole KO, Sayana MK, Onayemi F, et al. Analysis of revision procedures for failed unicondylar knee replacement. Ir J Med Sci. 2010;179: 361-4.

- Carstens EB, Lu A. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional analysis of the HindIII P region of a temperature-sensitive mutant of Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. J Gen Virol. 1990;71 ( Pt 12): 3035-40.

- Otte KS, Larsen H, Jensen TT, et al. Cementless AGC revision of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12: 55-9.

- Wynn Jones H, Chan W, Harrison T, et al. Revision of medial Oxford unicompartmental knee replacement to a total knee replacement: similar to a primary? Knee. 2012;19: 339-43.

- Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, et al. The routine of surgical management reduces failure after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83: 45-9.

- Rees JL, Price AJ, Beard DJ, et al. Minimally invasive Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: functional results at 1 year and the effect of surgical inexperience. Knee. 2004;11: 363-7.

- Perkins TR, Gunckle W. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: 3- to 10-year results in a community hospital setting. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17: 293-7.

- Barrett WP, Scott RD. Revision of failed unicondylar unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69: 1328-35.

- Pearse AJ, Hooper GJ, Rothwell A, et al. Survival and functional outcome after revision of a unicompartmental to a total knee replacement: the New Zealand National Joint Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92: 508-12.

- Hang JR, Stanford TE, Graves SE, et al. Outcome of revision of unicompartmental knee replacement. Acta Orthopaedica. 2010;81: 95-98.

- Robb CA, Matharu GS, Baloch K, et al. Revision surgery for failed unicompartmental knee replacement: technical aspects and clinical outcome. Acta Orthop Belg. 2013;79: 312-7.

- Aleto TJ, Berend ME, Ritter MA, et al. Early failure of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty leading to revision. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23: 159-63.

- Citak M, Cross MB, Gehrke T, et al. Modes of failure and revision of failed lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasties. Knee. 2015;22: 338-40.

- Saragaglia D, Bonnin M, Dejour D, et al. Results of a French multicentre retrospective experience with four hundred and eighteen failed unicondylar knee arthroplasties. Int Orthop. 2013;37: 1273-8.

- Hawi N, Plutat J, Kendoff D, et al. Midterm results after unicompartmental knee replacement with all-polyethylene tibial component: a single surgeon experience. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2016;136: 1303-7.

- Berger RA, Meneghini RM, Sheinkop MB, et al. The progression of patellofemoral arthrosis after medial unicompartmental replacement: results at 11 to 15 years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004: 92-9.