Review Article - Biomedical Research (2017) Volume 28, Issue 1

Anesthesia awareness versus memory impairment: can we reach an optimal balance to avoid both?

Liming Lei1#, Xiaofeng Shen1#, Shiqin Xu1#, Wei Wang1, Yusheng Liu1, Haibo Wu1 and Fuzhou Wang1,2*1Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, 210004, PR China

2Division of Neuroscience, The Bonoi Academy of Science and Education, Chapel Hill, NC-27510, USA

#These authors contributed equally to this work

- *Corresponding Author:

- Fuzhou Wang

Department of Anesthesiology

Nanjing Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, Nanjing Medical University

Nanjing 210004, PR China

Accepted date: June 11, 2016

Abstract

A noteworthy endpoint of general anesthesia is the loss of memory. However, a ghastly difficulty of narcosis is the anesthesia awareness, a rare condition that happens when surgical patients can review their surroundings or an occasion identified with their surgery while they are under general anesthesia. Amid general anesthesia, the amnesia is, for the most part, accomplished with general anesthetic drugs, either intravenous or inhaled. In this process, diverse classes of drugs can be administered to achieve the goal of memory loss. There exists a “seesaw balance” between anesthesia awareness and memory impairment, i.e. light anesthesia is prone to cause intraoperative awareness, whereas deep anesthesia would damage memory irreversibly. How can the clinical anesthesia maintain the “balance” where neither anesthesia awareness nor memory impairment occurred? Is the intraoperative monitor good enough in keep these two terrible things away? Therefore, beginning from a brief portrayal of anesthesia awareness and memory impairment, then we concentrate on the anesthesia monitoring, the way to avoid the likelihood of both awareness and memory impairment amid general anesthesia. Through in-depth discussion, we proposed that a theoretical optimal anesthesia interval or window exists by depicting individual curves of consciousness and memory changes upon general anesthesia. Although it is not that easy for getting such predictable curves prior to anesthesia using currently available techniques, its clinical implications are indubitable, and it is hopeful for us to avoiding both anesthesia awareness and memory impairment via relying on this anesthesia interval or window.

Keywords

General anesthesia, Anesthesia awareness, Memory impairment, Seesaw balance, Anesthesia monitor, Predictable curve.

Introduction

During general anesthesia, awareness is the postoperative recall of sensory perception. The incidence is approximately 1-2 per each 1,000 adult patients [1]. This uncommon yet genuine unfriendly occasion can be amazingly troubling for both the patient and the anesthesiologist. Awareness during anesthesia may occur despite apparently sound anesthetic management and is usually not related with pain [2]. However, a couple cases may encounter horrifying torment and have long haul neuropsychiatric sequelae like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [3]. This adverse event can also have serious medico legal insinuation. The incidence of awareness is markedly decreased through watchful checking of medications, measurements and hardware, close observation, and cautiousness during the anesthesia. Currently, the risk elements for anesthesia awareness are the performer who is the junior learner without supervision and the utilization of the neuromuscular blocks [4]. In addition to the anesthesia awareness, memory impairment is another thorny problem from much deeper anesthesia, which was considered as a way staying away from the intraoperative awareness. Cumulating evidence from clinical and animal studies indicated that the deeper the anesthesia with higher concentrations of general anesthetics, the worse the impairment of memory and cognition [5-7]. So it is not that easy for anesthesiologists to anesthetize patients to the optimal point where both awareness and memory impairment could be avoided, i.e. reaching the accurate and precise anesthesia level and maintain this balance to prevent these two nosocomial events. For clinical anesthesia, intraoperative monitors over different types of physiological factors are regarded as the potential solution to these problems [8]. Can monitor itself give us adequate information of the depth of anesthesia, from which we can adjust the anesthetic drugs to stay at the optimal anesthesia level? In this review, we will discuss these issues at length and present our point view on them.

Anesthesia Awareness

By using medications during surgical procedures, anesthesia is a way to control pain and consciousness. General anesthesia has been linked with intraoperative awareness from the time of its inception when the patient has not been given enough of the general anesthetics to make the patient be unconscious during anesthesia. Anesthesia awareness therefore turned into a vital subject of interest, that brings about genuine, and conceivably crippling, mental damage that eventually advances to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [3,9]. Awareness is typically characterized essentially as the patient recollecting an occasion that happened during anesthesia. An extra example of anesthesia awareness is awake paralysis, during which the unequivocal review of tangible discernments happened amid anesthesia [10].

For preventing and managing anesthesia awareness, each institute where general anesthesia can be administered should have a clear and strict protocol on this issue. The fact is that there are different levels of consciousness, in which alertness and general anesthesia are two extremes [11]. Amidst the range, conscious sedation is a special example that alludes to an awareness contingent upon the extent to which a patient is required to be quiet but conscious during surgery [12], of which gives a sheltered and agreeable anesthetic while keeping up the patient’s ability to follow commands [13]. Of course, under most circumstances, general anesthesia is required indicating that the patient should be totally unconscious and oblivious. So according to the range, the anesthesia first needs to reach some extent that can be regarded as general anesthesia that would reduce the incidence of awareness substantially. Although anesthesia awareness does not necessarily imply pain or discomfort [14], it is still a stress evoker that will cause the patient being in psychological anxiety, some even into PTSD, and have long-lasting after-effects, like bad dreams, night fear, flashbacks, sleeping disorder, and even suicide [15].

Whether or not a patient recollects the system largely relies on the assortment of pharmaceuticals utilized and measures monitored. One important fact is the administration of muscle relaxants that pushes the frequency of anesthesia awareness to a higher level and produces much worse sequelae [16]. It is understandable that muscle relaxants can provide surgeons with ideal operation view and anesthesiologists with best condition for tracheal intubation. Nonetheless, these are exactly the very drugs making the anesthesia professionals relax their vigilance over awareness due to patient’s inability to move. Under these conditions, the patient has a large probability to encounter far worse surgical torments, not only anesthesia awareness, but also pain and discomforts from surgical procedures [17]. For anesthesiologists and surgeons, they can realize and find clues to avoid these through some signs and abnormal changes if they are watchful enough. The worst thing, the thing we do not want to see, is such muscle relaxant-related inadequate anesthesia happened and lasted for a relatively longer period, even to the end of the surgery. Most anesthesia-associated cases sued by patients were related to anesthesia awareness [18]. As thus, it is that essential for anesthesiologists to keep alert for the changes of patient’s signs and monitored items to prevent anesthesia awareness from happening. It is not only for anesthesiologist’s benefit, but more importantly, also for patient’s wellbeing. Therefore, in term of the alertness over patient’s changes during anesthesia, it is the required professional characteristic of anesthesiologists as well as their inescapable responsibility.

In current days, anesthesia monitoring is the only reliable way for clinical anesthesiologists to depend on to keep their eyes on patient’s instantaneous alterations [19]. On the screens of different monitoring machines, a lot of parameters there need to be watched and analyzed. No matter whatever monitored, the final real purpose is to reach an ideal anesthesia state for surgeries. But this ideal state does not mean the optimal one because it may be much deeper than the expected, but it was still considered ideal for the surgeons: no moving, no awareness, nice operation view, and relatively stable life signs etc. However, such “ideal” anesthesia would result in another problem: memory impairment.

Memory Impairment from Anesthesia

People who underwent general anesthesia may wind up with memory and cognitive deficits for days or weeks after surgery [20]. For elderly patients, general anesthesia is strongly associated with the possibility of Alzheimer’s disease, a disease characterized with memory loss and dementia [21]. For child patients, this negative effect would be more serious. A number of clinical reports [22-25] and animal researches [26-29] have disclosed that general anesthesia is a risk factor for kids’ learning and abstract thinking when they had been exposed to general anesthetics, especially when they are younger than 3 years; and further this effect would be worse if the exposure time was longer and density was higher [30]. First of all, such impact of general anesthetics on memory or learning is from the drugs’ own property, even though the precise underlying mechanisms are largely unknown, it is certain that these drugs intervene with the normal function of individual neuron or the neuronal circuit [31]. Secondly, this impact is closely related to the anesthesia process, which includes anesthesia depth, duration, and drug selection [32]. Of these, anesthesia duration and drug selection are two fixed aspects that are difficult to be changed for different institutes and surgeries. So only the anesthesia depth is the one that can be adjusted individually.

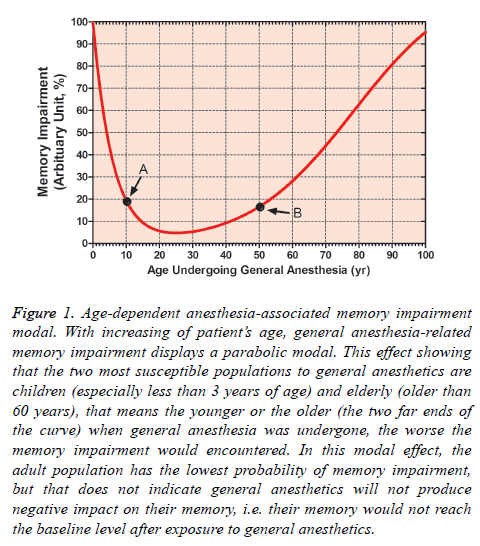

What we first need to keep in mind is the fact that anesthesiainduced memory impairment is an age-dependent phenomenon, i.e. kids and elderly are two susceptible populations, and this kind of distribution is similar to the parabolic modal effect, of which two major different populations are mainly affected at the two far ends of the curve [33]. Of course, this does not mean the healthy adult patients will not be impacted by general anesthetics. They also display various extent of memory impairment that lasts days to weeks after general anesthesia (Figure 1) [6,20,34]. In addition, the level of memory impairment is correlated with many factors like race, gender, health status, smoking, psychological stress, and genome etc [35]. With the exception of these individual confounding factors, the only thing left for anesthesiologists to control is the anesthesia depth. In combination with the abovementioned anesthesia awareness, anesthesia-induced memory impairment theoretically can be alleviated to the minimal extent if the anesthesia was control to the optimal level. So clinical monitoring on the anesthetized patients is the only hope for solving these two issues: anesthesia awareness versus memory impairment. Can we really reach this goal via currently available monitoring methods?

Figure 1: Age-dependent anesthesia-associated memory impairment modal. With increasing of patient’s age, general anesthesia-related memory impairment displays a parabolic modal. This effect showing that the two most susceptible populations to general anesthetics are children (especially less than 3 years of age) and elderly (older than 60 years), that means the younger or the older (the two far ends of the curve) when general anesthesia was undergone, the worse the memory impairment would encountered. In this modal effect, the adult population has the lowest probability of memory impairment, but that does not indicate general anesthetics will not produce negative impact on their memory, i.e. their memory would not reach the baseline level after exposure to general anesthetics.

Anesthesia Monitoring: The Way to Optimize the Balance between Anesthesia Awareness and Memory Impairment?

Anesthesia monitor is the most reliable technique available currently that can provide anesthesiologists with relatively precise data on patient’s general state of anesthesia, which includes vital signs, concentrations of anesthetics, pressure of CO2, anesthesia depth, fluid, electrolytes and acid-base balance, and saturation of O2 etc. All these parameters should be analyzed comprehensively and simultaneously to get the information about the patient’s real time state of anesthesia. However, it is not every patient needs to be monitored over all these above-mentioned measures that are divided into invasive and non-invasive ones. From the guidelines recommended by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), general anesthesia should be basically monitored and evaluated continuously with patient’s oxygenation, ventilation, circulation, and temperature [36]. These basic monitors can only guarantee the vital signs of the patient to fluctuate within a reasonable range, but cannot tell the precise level of anesthesia. So the depth of anesthesia was not considered as one of the basic monitors by ASA in this monitor standard, but the National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) recommended electroencephalogram (EEG)-base monitor of anesthesia depth in patients receiving general anesthesia [37]. In fact, in ASA’s earlier Task Force Advisory, the monitor of anesthesia depth has been suggested to avoid anesthesia awareness [38]. Although it is widely accepted nowadays about the monitor of anesthesia depth in practice, its eventual purpose is to prevent anesthesia awareness, but rather memory impairment. The indisputable reality is that no literatures there mentioned this issue: can the monitor of anesthesia depth be used for preventing memory impairment?

Current available methods for monitoring anesthesia depth majorly include Bispectral Index (BIS), E-Entropy, and Narcotrend-Compact M. All of them are EEG-based techniques, which tell the information of the electrical movement of the cerebral cortex that is dynamic when alert whereas tranquil when anesthetized [39]. Of BIS, a gauge ranged from “0” to “100” was used to scale the conscious level. For patients undergoing general anesthesia, it is typically recommended to keep a number somewhere between 40 and 60 reflecting a low probability of intraoperative consciousness [8,40]. Studies intended to evaluate the correlation between BIS value and anesthesia awareness, but did not get confirmatory results [41,42], and a large range of recommended BIS values (20 to 58) was given for anesthesia during surgical procedures [43]. However, some patients still experiences intraoperative awareness despite the monitored BIS values showing an adequate depth of anesthesia [44,45]. Moreover, other reported observed that BIS itself could be affected by several factors including patient’s conditions [46], muscle relaxants [47], warming or hypothermia [48], cerebral ischemia and reperfusion [49], gas embolism [50], and unrecognized hemorrhage [51]. As thus, BIS cannot be the reliable method for monitoring anesthesia awareness, nor be a way for memory impairment because memory detection is much more difficult to be measured than awareness.

E-Entropy describes the complexity, irregularity, or unpredictability of an electrical signal, and is independent of the absolute measures like the frequency and amplitude of the signal. There are two entropy values can be separately reported: state entropy (SE, ranging from 0 to 91) and response entropy (RE, ranging from 0 to 100) [52]. SE reflects patient’s cortical state, but RE denotes muscle electrical activity. The reference ranges for SE and RE are recommended showing that during general anesthesia, i.e. SE can be at 50-63 and RE can be at 34-52 [53]. Do these suggested numbers guarantee the final result of anesthesia? Several cases were reported that anesthesia awareness was experienced despite the lower entropy, even at “0” [54-56]. Besides, entropy monitor displayed its drawbacks in telling the depth of anesthesia. Entropy cannot correctly detect the burst depression from overdose anesthetics [57], and cannot produce expected response to intracerebral procedures [58], and cannot reflect real time hypnotic state [59]. Again, still no data were presented whether entropy monitor can be used for predicting memory impairment after general anesthesia.

Narcotrend-Compact M is a system to visually classify the EEG patterns. Originally, the raw EEG was classified as follows: A (awake), B (sedated), C (light anesthesia), D (general anesthesia), E (general anesthesia with deep hypnosis), and F (general anesthesia with increasing burst suppression). This alphabet-based scale now has been converted into a quantitative index (Narcotrend® Index), which changes from 0 (deeply anesthetized) to 100 (awake) [60]. Although Narcotrend displayed superior role in anesthesia depth monitor to sole clinical assessment [61], several studies did not find reliable relationship between Narcotrend and intraoperative awareness or loss of consciousness [62-64]. Furthermore, Narcotrend can be influenced by patient’s muscle activity measured with electromyography [65]. Regarding anesthesia-associated memory impairment monitored with Narcotrend, we do not have any reports on this topic. So it is also hard to say that Narcotrend can be used as a reliable method for monitoring anesthesia awareness and memory impairment.

In addition to above-mentioned three commonly recognized EEG-based techniques, there are other methods like Patient State Index, SNAP Index, and Cerebral State Monitor/Cerebral State Index were introduced to detect patient’s consciousness under general anesthesia, whereas currently available data also cannot provide solid evidence upon the use of these three methods in measuring the depth of general anesthesia [66-68]. So theoretically these EEG-related monitoring techniques could provide clinical anesthesia adequate information on the depth of anesthesia, and could be used as the way for detecting intraoperative awareness; the fact however is that they failed in doing so. First, all the EEG-based monitors belong to the nonevoking state detection that only records the changes of cortical activities per se under general anesthesia. Second, as far as the techniques concerned, they are passive recorders that function only by presenting the alterations detected stationarily. Therefore, it is understandable that everything affecting the cerebral activities will disturb the expected recordings of the monitor-recorded tracings [44-51,57-59,65].

Auditory evoked potentials (AEPs), an evoked electrical response to auditory sound stimuli delivered via headphones, record the activities of the brainstem. Although brainstem is not that sensitive to anesthetics, it was found that the increasing concentrations of general anesthetics can evoke predictable changes in the middle-latency AEPs (MLAEPs) [69]. Nowadays, MLAEPs are considered as one relatively reliable method of monitoring the depth of general anesthesia. The classic response of AEPs to escalating anesthetic concentrations is the elongated latency and diminished amplitude of the waves. When correlate MLAEPs to different concentrations of anesthetics, the AEP Index (AAI) was introduced that the scale ranged from “0” to “100”, and recommended that the AAI should be at least less than 25 (range: 21.1-37.8) for anesthesia maintenance to keep a low probability of consciousness. AAI has shown great potential in detecting anesthesia awareness [70], but it is not the ideal solution for preventing all the incidence of awareness [71]. In further, AAI cannot be used as an index for memory formation during anesthesia [72], and we do not have any data depicting the role of AAI as a tool to measure the memory impairment from general anesthesia.

As mentioned above, the techniques available today in clinical anesthesia for depth monitoring are not good enough to keep all incidences of intraoperative awareness totally away. The ascertained thing is that these monitors cannot be regarded as the standard totally relied on, but only should be treated as references for consciousness control, and needs to be assessed comprehensively in combination with patient’s individual conditions and physiological changes during general anesthesia. When considering these monitors for anesthesiaassociated memory impairment, it is far more difficult for anesthesiologists to achieve this goal through these techniques due to: (i) no dataset was established currently on the relationship between anesthesia depth and memory impairment; (ii) time-dependent alterations in learning, cognition, and memory after general anesthesia makes such kind of monitor be hard to be realized; (iii) the debate between anesthesia advocators and skeptics on the negative effect of general anesthetics on patients memory is still ongoing, which would undoubtedly impede the efforts for researchers to find the way to reduce the possibility of memory impairment; (iv) under current clinical situation, the would-be change in memory from general anesthesia can be overlooked if compared with the harmfulness of the disease itself because surgery overweighs the potential damage of memory by general anesthetics.

How to establish the Balance between Anesthesia Awareness and Memory Impairment?

The good thing for clinical anesthesia is the synthesis and administration of general anesthetics (intravenous and inhalational) to reach the goal of absolute anesthesia, but the bad thing is that we still do not clearly understand the underlying mechanisms of these drugs. This is the major reason why we now cannot figure out a reliable method to monitor the changes of consciousness based on the drug’s mechanisms. In addition, the complexity of the cerebral center is another reason why we cannot use sole measuring method to tell the actual level of anesthesia. Given consciousness and memory are two distinct processes that involve different neurotransmitters and various neuronal circuits, and general anesthetics exert different levels of impact on these molecules and nervous systems, then this neural complexity makes it hard to find a way to detect the precise level of anesthesia using currently available knowledge.

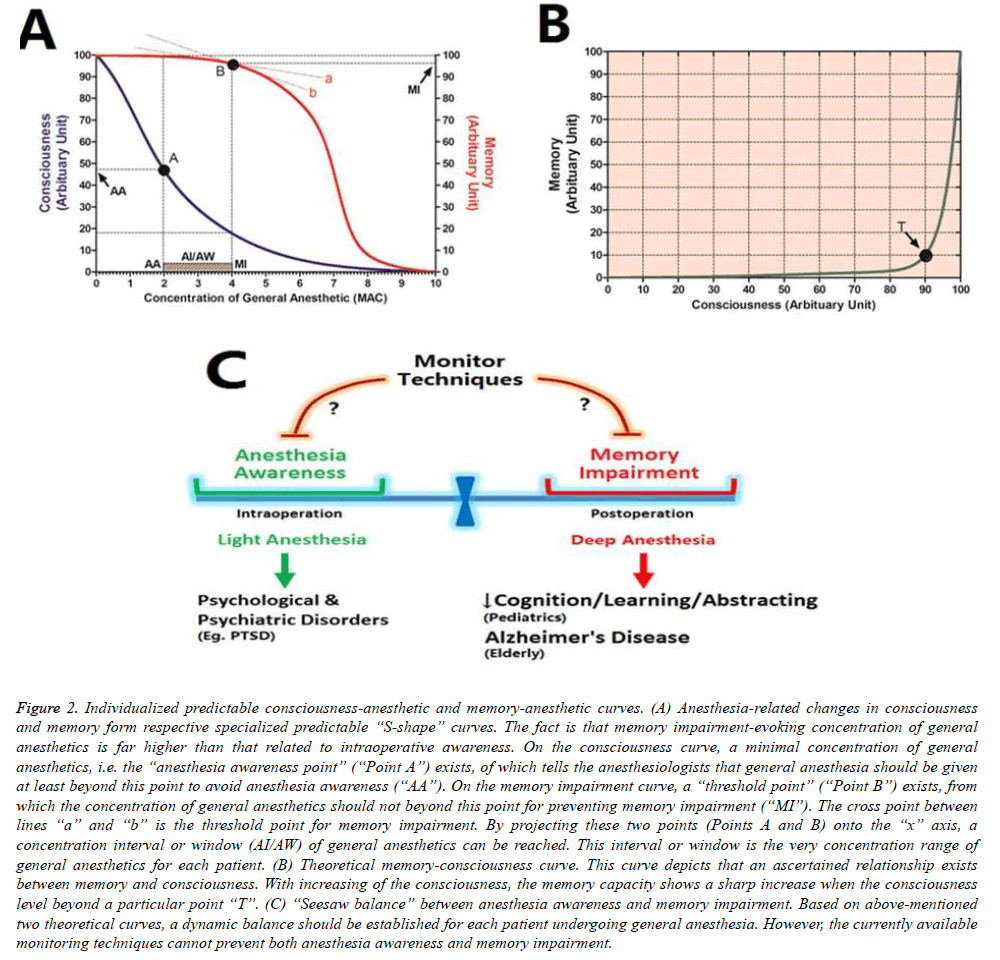

As depicted in our hypothesized modal (Figure 2), a balance interval between anesthesia awareness and memory impairment exists during the performance of general anesthesia, from which we suggest that anesthesia maintenance should fluctuate within this interval. Furthermore, we proposed that this interval is changeable with different patients, i.e. it is an individualized measure that is strongly associated with the patient’s conditions.

Figure 2: Individualized predictable consciousness-anesthetic and memory-anesthetic curves. (A) Anesthesia-related changes in consciousness and memory form respective specialized predictable “S-shape” curves. The fact is that memory impairment-evoking concentration of general anesthetics is far higher than that related to intraoperative awareness. On the consciousness curve, a minimal concentration of general anesthetics, i.e. the “anesthesia awareness point” (“Point A”) exists, of which tells the anesthesiologists that general anesthesia should be given at least beyond this point to avoid anesthesia awareness (“AA”). On the memory impairment curve, a “threshold point” (“Point B”) exists, from which the concentration of general anesthetics should not beyond this point for preventing memory impairment (“MI”). The cross point between lines “a” and “b” is the threshold point for memory impairment. By projecting these two points (Points A and B) onto the “x” axis, a concentration interval or window (AI/AW) of general anesthetics can be reached. This interval or window is the very concentration range of general anesthetics for each patient. (B) Theoretical memory-consciousness curve. This curve depicts that an ascertained relationship exists between memory and consciousness. With increasing of the consciousness, the memory capacity shows a sharp increase when the consciousness level beyond a particular point “T”. (C) “Seesaw balance” between anesthesia awareness and memory impairment. Based on above-mentioned two theoretical curves, a dynamic balance should be established for each patient undergoing general anesthesia. However, the currently available monitoring techniques cannot prevent both anesthesia awareness and memory impairment.

So the key question is that how we can calculate this interval predictably through individual’s consciousness curve according to patient’s conditions prior to surgeries. If we can do that that means we also can reach the anesthesia state, under which neither intraoperative awareness nor memory impairment will we encounter. Therefore, several prerequisites are needed when we are working on establishing this individualized curve: (i) Preoperative assessment of patient’s EEG or AAI is an indispensable aspect, from which the basic predictable curve can be built up. (ii) Much more in-depth understanding of the EEG or AAI waves is needed. (iii) Patient’s gender, age, height, weight, and alcohol drinking status etc. can be used to adjust the curve precisely. (iv) Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) can be used as a tool to assess the consciousness state for establishing the curve. (v) Reliable tracer agent that can specifically bind to cerebral targets to display the consciousness state is required to be detected by fMRI. (vi) The specific cerebral target molecule reflecting consciousness is needed to be found. (vii) The necessity of preoperative fMRI should be assessed sufficiently to answer the question that the benefit of fMRI assessment overweighs anesthesia awareness and memory impairment.

From this modal, we believe that in the near future, establishment of individualized predictable consciousness curve before general anesthesia would be possible, no matter what assessing methods will be used. Besides, this should become one preoperative item assessed routinely. Of course, this will undoubtedly based on the breakthrough of many technical advancements and performance of in-depth researches on corresponding above-mentioned interrelationships. Through this, we do not want to see intraoperative awareness any more, and also do not want to hear patient’s complaint about memory impairment any longer. It would be true someday.

Concluding Remarks

General anesthesia is one of the major techniques available for nowadays clinical anesthesia, but anesthesia awareness and memory impairment are two critical types of indelibility markedly affecting patient’s wellbeing. It is not that easy for anesthesiologists to avoid both anesthesia awareness and memory impairment via currently used EEG-based monitoring techniques and AAI. If using deep anesthesia to prevent intraoperative awareness, memory impairment would result from; but if using light anesthesia to stay away from memory impairment, anesthesia awareness would appear. For this dilemma, we hypothesized that a balance interval or an optimal anesthesia window exists between them, which can be established through individualized consciousness-anesthetic and memory-anesthetic curves. This predictable interval or window will guide clinical anesthesia into a relatively more reliable and safer state.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Scientific Foundation of China (81271242, 81371248), Nanjing Medical University Medical Science Development Grant (2014NMUZD043, 2014NJMU092), and The Reagan Louis Research Foundation (R105BS0100) USA.

References

- Mashour GA, Avidan MS. Intraoperative awareness: controversies and non-controversies. Br J Anaesth 2015; 115: i20- i26.

- Rule E, Reddy S. Awareness under general anaesthesia. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2014; 75: 573-577.

- Whitlock EL, Rodebaugh TL, Hassett AL, Shanks AM, Kolarik E, Houghtby J. Psychological sequelae of surgery in a prospective cohort of patients from three intraoperative awareness prevention trials. Anesth Analg 2015; 120: 87-95.

- Sanderson PM, Watson MO, Russell WJ, Jenkins S, Liu D, Green N. Advanced auditory displays and head-mounted displays: advantages and disadvantages for monitoring by the distracted anesthesiologist. Anesth Analg 2008; 106: 1787-1797.

- Shen X, Liu Y, Xu S, Zhao Q, Guo X, Shen R, Wang F. Early life exposure to sevoflurane impairs adulthood spatial memory in the rat. Neurotoxicology 2013; 39: 45-56.

- Armstrong R, Xu F, Arora A, Rasic N, Syed NI. General anesthetics and cytotoxicity: possible implications for brain health. Drug Chem Toxicol 2016; 2: 1-9.

- Vlisides P, Xie Z. Neurotoxicity of general anesthetics: an update. Curr Pharm Des 2012; 18: 6232-6240.

- Escallier KE, Nadelson MR, Zhou D, Avidan MS. Monitoring the brain: processed electroencephalogram and peri-operative outcomes. Anaesthesia 2014; 69: 899-910.

- Laukkala T, Ranta S, Wennervirta J, Henriksson M, Suominen K, Hynynen M. Long-term psychosocial outcomes after intraoperative awareness with recall. Anesth Analg 2014; 119: 86-92.

- Cascella M, Schiavone V, Muzio MR, Cuomo A. Consciousness fluctuation during general anesthesia: a theoretical approach to anesthesia awareness and memory modulation. Curr Med Res Opin 2016; 5: 1-9.

- Pandit JJ. Acceptably aware during general anaesthesia: 'dysanaesthesia'--the uncoupling of perception from sensory inputs. Conscious Cogn 2014; 27: 194-212.

- Brinjikji W, Murad MH, Rabinstein AA, Cloft HJ, Lanzino G, Kallmes DF. Conscious sedation versus general anesthesia during endovascular acute ischemic stroke treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 525-529.

- Davidson AJ, Huang GH, Czarnecki C, Gibson MA, Stewart SA, Jamsen K, Stargatt R. Awareness during anesthesia in children: a prospective cohort study. Anesth Analg 2005; 100: 653-661.

- Bogod D, Orton J, Oh T. Detecting awareness during general anaesthetic caesarean section. Anaesthesia 1990; 45: 279-284.

- Aceto P, Perilli V, Lai C, Sacco T, Ancona P, Gasperin E, Sollazzi L. Update on post-traumatic stress syndrome after anesthesia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2013; 17: 1730-1737.

- Gazzanelli S, Vari A, Tarquini S, Fermariello A, Caputo M, Almansour M. Monitoring of consciousness with BIS during induction of anesthesia. Which muscle relaxant? G Chir 2005; 26: 163-169.

- Cascella M, Bifulco F, Viscardi D, Tracey MC, Carbone D, Cuomo A. Limitation in monitoring depth of anesthesia: a case report. J Anesth 2016; 30: 345-8.

- Glannon W. Intraoperative awareness: consciousness, memory and law. J Med Ethics 2014; 40: 663-664.

- Shanks AM, Avidan MS, Kheterpal S, Tremper KK, Vandervest JC, Cavanaugh JM, Mashour GA. Alerting thresholds for the prevention of intraoperative awareness with explicit recall: a secondary analysis of the Michigan Awareness Control Study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2015; 32: 346-353.

- Cascella M. The Impact of anesthetics drugs on memory and memory modulation under general anesthesia. J In Silico In Vitro Pharmacol 2015; 1:6.

- Inan G, Özköse Satirlar Z. Alzheimer disease and anesthesia. Turk J Med Sci 2015; 45: 1026-1033.

- Aun CS, McBride C, Lee A, Lau AS, Chung RC, Yeung CK. Short-term changes in postoperative cognitive function in children aged 5 to 12 years undergoing general anesthesia: a cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e3250.

- Lee JH, Zhang J, Wei L, Yu SP. Neurodevelopmental implications of the general anesthesia in neonate and infants. Exp Neurol 2015; 272: 50-60.

- Stratmann G, Lee J, Sall JW, Lee BH, Alvi RS, Shih J. Effect of general anesthesia in infancy on long-term recognition memory in humans and rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014; 39: 2275-2287.

- Williams RK. The pediatrician and anesthesia neurotoxicity. Pediatrics. 2011; 128: e1268- e1270.

- Song Q, Ma YL, Song JQ, Chen Q, Xia GS, Ma JY, et al. Sevoflurane induces neurotoxicity in young mice through FAS/FASL signaling. Genet Mol Res 2015; 14: 18059-18068.

- Qiu L, Zhu C, Bodogan T, Gómez-Galán M, Zhang Y, Zhou K. Acute and long-term effects of brief sevoflurane anesthesia during the early postnatal period in rats. Toxicol Sci 2016; 149: 121-133.

- Chung W, Park S, Hong J, Park S, Lee S, Heo J. Sevoflurane exposure during the neonatal period induces long-term memory impairment but not autism-like behaviors. Paediatr Anaesth 2015; 25: 1033-1045.

- Lobo FA, Guimarães J, Schraag S, Engbers F. The effect of general anaesthesia on memory in children. Anaesthesia 2014; 69: 1062.

- Lin EP, Soriano SG, Loepke AW. Anesthetic neurotoxicity. Anesthesiol Clin 2014; 32: 133-55.

- Mellon RD, Simone AF, Rappaport BA. Use of anesthetic agents in neonates and young children. Anesth Analg 2007; 104: 509-520.

- Gleich S, Nemergut M, Flick R. Anesthetic-related neurotoxicity in young children: an update. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2013; 26: 340-7.

- Lu K. Distribution of the two-sample t-test statistic following blinded sample size re-estimation. Pharm Stat 2016; 15: 208-215.

- Xu X, Tian Y, Wang G, Tian X. Inhibition of propofol on single neuron and neuronal ensemble activity in prefrontal cortex of rats during working memory task. Behav Brain Res 2014; 270: 270-276.

- Flick RP, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Wilder RT, Voigt RG, Olson MD, et al. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes after early exposure to anesthesia and surgery. Pediatrics 2011; 128: e1053-1061.

- Standards for Basic Anesthetic Monitoring. The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), Standards and Practice Parameters. 2015.

- NICE recommends depth of anaesthesia monitors 2016.

- American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Intraoperative Awareness. Practice advisory for intraoperative awareness and brain function monitoring: a report by the american society of anesthesiologists task force on intraoperative awareness. Anesthesiology 2006; 104: 847-864.

- Chang JJ, Syafiie S, Kamil R, Lim TA. Automation of anaesthesia: a review on multivariable control. J Clin Monit Comput 2015; 29: 231-239.

- Halliburton JR, McCarthy JE. Perioperative monitoring with the electroencephalogram and the bispectral index monitor. AANA 2000; 68: 333-340

- Mousavi SM, Adamo?lu A, Demiralp T, Shayesteh MG. A wavelet transform based method to determine depth of anesthesia to prevent awareness during general anesthesia. Comput Math Methods Med 2014; 2014: 354739.

- Zand F, Hadavi SM, Chohedri A, Sabetian P. Survey on the adequacy of depth of anaesthesia with bispectral index and isolated forearm technique in elective Caesarean section under general anaesthesia with sevoflurane. Br J Anaesth 2014; 112: 871-878.

- Bowdle TA. Depth of anesthesia monitoring. Anesthesiol Clin 2006; 24: 793-822.

- Mychaskiw G II, Horowitz M, Sachdev V, Heath BJ. Explicit intraoperative recall at a bispectral index of 47. Anesth Analg 2001; 92: 808-809.

- Rampersad SE, Mulroy MF. A case of awareness despite an “adequate depth of anesthesia” as indicated by a bispectral index monitor. Anesth Analg 2005; 100: 1363-1364.

- Hemmerling TM, Fortier JD. Falsely increased bispectral index values in a series of patients undergoing cardiac surgery using forced-air-warming therapy of the head. Anesth Analg 2002; 95: 322-323.

- Vivien B, Di Maria S, Ouattara A, Langeron O, Coriat P, Riou B. Overestimation of Bispectral Index in sedated intensive care unit patients revealed by administration of muscle relaxant. Anesthesiology 2003; 99: 9-17.

- Hemmerling TM, Fortier JD. Falsely increased bispectral index values in a series of patients undergoing cardiac surgery using forced-air-warming therapy of the head. Anesth Analg 2002; 95: 322-323.

- Kakinohana M, Miyata Y, Kawabata T, Kawashima S, Tokumine J, Sugahara K. Bispectral Index decreased to “0” in propofol anesthesia after a cross-clamping of descending thoracic aorta. Anesthesiology 2003; 99: 1223-1225.

- Kiribayashi M, Nakasone M, Moriyama N, Mochida S, Yamasaki K, Minami Y, Inagaki Y. Multiple cerebral infarction by air embolism associated with remarkable low BIS value during lung segmentectomy with video assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) technique: a case report. Masui 2010; 59: 480-483.

- Brallier JW, Deiner SG. Use of the bilateral BIS monitor as an indicator of cerebral vasospasm in ICU patients. Middle East J Anaesthesiol 2013; 22: 161-164.

- Vakkuri A, Yli-Hankala A, Sandin R, Mustola S, Høymork S, Nyblom S, et al. Spectral entropy monitoring is associated with reduced propofol use and faster emergence in propofol–nitrous oxide–alfentanil anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2005; 103: 274-279.

- Vanluchene ALG, Struys MMRF, Heyse BEK, Mortier EP. Spectral entropy measurement during propofol and remifentanil: A comparison with the bispectral index. Br J Anaesth 2004; 93: 645-654.

- Yli-Hankala A. Awareness despite low spectral entropy values. Anesth Analg 2008; 106: 1585.

- Vassiliadis M, Geros D, Maria K. Awareness despite low spectral entropy values. Anesth Analg 2007; 105: 535.

- Jiang GJ, Fan SZ, Abbod MF, Huang HH, Lan JY, Tsai FF. Sample entropy analysis of EEG signals via artificial neural networks to model patients' consciousness level based on anesthesiologists experience. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 343478.

- Hart SM, Buchannan CR, Sleigh JW. A failure of M-Entropy to correctly detect burst suppression leading to sevoflurane overdosage. Anaesth Intensive Care 2009; 37: 1002-1004.

- Clanet M, Bonhomme V, Lhoest L, Born JD, Hans P. Unexpected entropy response to saline spraying at the end of posterior fossa surgery: a few cases report. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg 2011; 62: 87-90.

- Kreuzer M, Zanner R, Pilge S, Paprotny S, Kochs EF, Schneider G. Time delay of monitors of the hypnotic component of anesthesia: analysis of state entropy and index of consciousness. Anesth Analg 2012; 115: 315-319.

- Kreuer S, Wilhelm W. The Narcotrend monitor. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2006; 20: 111-119.

- D'Mello O. Narcotrend-assisted propofol/remifentanil anaesthesia for prevention of awareness. Br J Anaesth 2008; 100: 421.

- Schneider G, Kochs EF, Horn B, Kreuzer M, Ningler M. Narcotrend does not adequately detect the transition between awareness and unconsciousness in surgical patients. Anesthesiology 2004; 101: 1105-1111.

- Russell IF. The Narcotrend 'depth of anaesthesia' monitor cannot reliably detect consciousness during general anaesthesia: an investigation using the isolated forearm technique. Br J Anaesth 2006; 96: 346-352.

- Kreuer S, Bruhn J, Ellerkmann R, Ziegeler S, Kubulus D, Wilhelm W. Failure of two commercial indexes and spectral parameters to reflect the pharmacodynamic effect of desflurane on EEG. J Clin Monit Comput 2008; 22: 149-158.

- Panousis P, Heller AR, Burghardt M, Bleyl JU, Koch T. The effects of electromyographic activity on the accuracy of the Narcotrend monitor compared with the Bispectral Index during combined anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2007; 62: 868-874.

- Anderson RE, Sartipy U, Jakobsson JG. Use of conventional ECG electrodes for depth of anaesthesia monitoring using the cerebral state index: a clinical study in day surgery. Br J Anaesth 2007; 98: 645-648.

- Hrelec C, Puente E, Bergese S, Dzwonczyk R. SNAP II versus BIS VISTA monitor comparison during general anesthesia. J Clin Monit Comput 2010; 24: 283-288.

- White PF, Tang J, Ma H, Wender RH, Sloninsky A, Kariger R. Is the patient state analyzer with the PSArray2 a cost-effective alternative to the bispectral index monitor during the perioperative period? Anesth Analg 2004; 99: 1429-1435.

- Cagy M, Infantosi AF. Unconsciousness indication using time-domain parameters extracted from mid-latency auditory evoked potentials. J Clin Monit Comput 2002; 17: 361-366.

- De Cosmo G, Aceto P, Clemente A, Congedo E. Auditory evoked potentials. Minerva Anestesiol 2004; 70: 293-297.

- Trillo-Urrutia L, Fernández-Galinski S, Castaño-Santa J. Awareness detected by auditory evoked potential monitoring. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91: 290-292.

- Hadzidiakos D, Petersen S, Baars J, Herold K, Rehberg B. Comparison of a new composite index based on midlatency auditory evoked potentials and electroencephalographic parameters with bispectral index (BIS) during moderate propofol sedation. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2006; 23: 931-936.