Research Article - Biomedical Research (2017) Volume 28, Issue 5

Analysis of chest wall masses: a clinical study

Muharrem Cakmak*Gazi Yasargil Education and Research Hospital, Thoracic Surgery Clinic, Diyarbakir, Turkey

- *Corresponding Author:

- Muharrem Cakmak

Gazi Yasargil Education and Research Hospital

Thoracic Surgery Clinic, Diyarbakir, Turkey

Accepted date: September 27, 2016

Abstract

Materials and Methods: Eighty six patients treated for chest wall mass were evaluated. Chest wall masses were divided into 2 groups as masses originated from soft, cartilage or bone tissue and masses having anterior, lateral and posterior location. The rate, localization and histopathologic types of masses in each group were investigated. Results were analyzed using Fisher's exact test.

Findings: The mean age was 46.18 ± 10.16. 56 patients (65%) were male while 30 (35%) were female. 41 (48%) of the masses were originated in soft tissue, 23 (27%) were in cartilage, and 22 (25%) were in bone tissue. 46 (53%) of the masses were found to be located in anterior chest wall, 17 (20%) were in the lateral chest wall, and 23 (27%) were in the posterior chest wall. 54 of the masses (63%) were benign, whereas 32 (37%) were malignant. For reconstruction, muscle flaps and synthetic grafts were used. The possibility of chest wall masses being malignant was found to be significant in masses originated in bone.

Discussion: Malignancy should be strongly considered in chest wall tumors. A detailed history and physical examination are required for diagnosis.

Conclusion: The success of treatment depends on adequate resection as well as the type of tumor.

Keywords

Chest wall, Mass, Resection, Reconstruction

Introduction

The chest wall consists of soft, cartilage, and bone tissue. A large part of the masses are originated from soft tissue. Primary chest wall tumors are a heterogeneous group developing in bone and soft tissue. These tumors constitute 2% of all primary tumors of the body, and 5% of the tumors of the thorax. Malignancy rate is around 60-80%. Painful or painless swelling is the most common findings. The treatment is resection. Autologous tissue and various materials may also be needed for reconstruction [1-5]. In our study, we aimed to share the results of patients treated for chest wall masses.

Materials and Methods

Patients

A total of 86 patients treated for chest wall masses between 2004 and 2015 were evaluated.

Procedures

The files of the patients were analyzed retrospectively. Additionally, age, gender, symptoms and location of disease, radiological examinations, diagnosis and treatment, complications, length of stay, morbidity and mortality were investigated.

Chest wall masses in patients were divided into 2 groups of threes as masses originated from soft, cartilage or bone tissue and masses having anterior, lateral and posterior location [6].

The location between the right-left anterior axillary lines was accepted as anterior, the location between the anterior and posterior axillary lines was considered as lateral, and the location between the right and left posterior axillary lines was assessed as the posterior. The ratio of the masses, origin, location and histopathologic types were investigated.

Statistical analysis

In statistical analysis, continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables were explained as the number-ratio. The results were analyzed by Fisher's exact test [7]. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The mean age was 46.18 ± 10.16. 56 patients (65%) were male while 30 (35%) were female. Mass was located on the right in 43 (50%) patients, whereas it was on the left in 37 (43%), and in the sternum in 6 (7%).

The main symptoms of patients were painless swelling (n=51, 59%), painful swelling (n=35, 41%), cough (n=11, 13%), dyspnea (n=9, 10%), fever (n=9, 10%), pleural effusion (n=6, 7%), and nausea-vomiting (n=4, 5%). The main diagnostic methods were chest X-ray, thoracic CT, MRI, PET-CT, needle aspiration, tru-cut biopsy, and incisional and/or excisional biopsy.

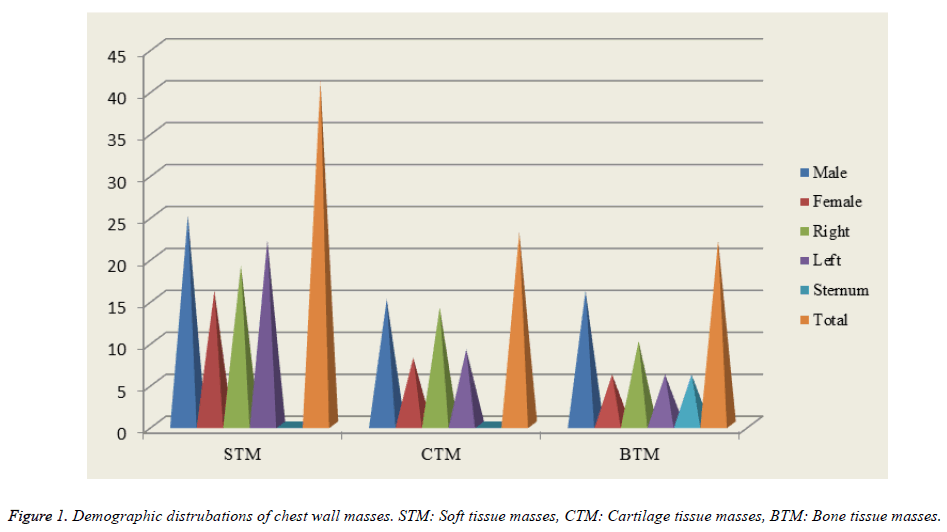

We discovered that 41 (48%) of the masses were originated in the soft tissue, 23 (27%) were originated in cartilage, and 22 (25%) were in the bone tissue (Figure 1). 25 (61%) of the patients who had soft tissue origin (n=41, 48%) were male while 16 (39%) were female. The mass was on the right in 19 (46%), whereas it was on the left in 22 (54%). 5 (12%) of masses were malignant and 36 (88%) were benign. 15 (65%) of the patients who had cartilage tissue origin (n=23, 27%) were male while 8 (35%) were female. The mass was on the right in 14 (61%) while it was on the left in 9 (39%). 11 (48%) of the masses were malignant whereas 12 (52%) were benign. 16 (73%) of the patients having bone tissue origin (n=22, 25%) were male while 6 (27%) were female. The mass was on the right in 10 (46%), on the left in 6 (27%), and in the sternum in 6 (27%) patients. 16 (73%) of the masses were malignant while 6 (27%) were benign (Table 1). The possibility of chest wall masses being malignant was found to be significant in bone originated masses.

| Number | Male | Female | P value | Right | Left | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STM | 41 | 3/22 | 2/14 | 1.0000 | 4/15 | 1/21 | 0.1644 |

| CTM | 23 | 6/9 | 5/3 | 0.4003 | 6/8 | 5/4 | 0.6802 |

| BTM | 22 | 12/4 | 4/2 | 1.0000 | 4/6 | 6/0 | 0.0338* |

| Total | 86 | 21/35 | 11/19 | 1.0000 | 14/29 | 12/25 | 1.0000 |

Table 1. Analysis according to origin of chest wall masses.

It was found that 46 (53%) of the masses were located in anterior, 17 (20%) were in lateral, and 23 (27%) were in the posterior. 10 (22%) of the anterior chest wall masses (n=46, 53%) were located in supraclavicular soft tissue, 1 (2%) was located in clavicle bone, 2 (4%) were located in infraclavicular soft tissue, 6 (13%) were in sternum, 23 (50%) were in rib cartilage, and 4 (9%) were located in the ribs. On the other hand, 11 (64%) of the lateral chest wall masses (n=17, 20%) were located in axillary soft tissue, 3 (18%) were in midaxillary line of soft tissue, and 3 (18%) were located in the ribs. As for posterior chest wall masses (n=23, 27%), we discovered that 4 (17%) were located in suprascapular soft tissue, 3 (13%) were in parascapular soft tissue, 8 (35%) were located in infrascapular soft tissue, and 8 (35%) were located in the ribs (Table 2).

| Compartment | Localization | Male | Female | Right | Left | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior chest wall (n: 46) | Supraclavicular ST | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Clavicular bone | - | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | |

| İnfraclavicular ST | 2 | - | - | 2 | 2 | |

| Sternum bone | 5 | 1 | - | - | 6 | |

| Rib cartilage | 15 | 8 | 14 | 9 | 23 | |

| Rib bone | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | |

| Lateral chest wall (n: 17) | Axillary cavity ST | 7 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| Mid-axillary line ST | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Rib bone | 3 | - | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Posterior chest wall (n: 23) | Suprascapular ST | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Parascapular ST | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| İnfrascapular ST | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| Rib bone | 5 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 8 | |

| Total (n: 86) | 56 | 30 | 43 | 37+6 | 86 |

Table 2. Distrubations according to localization of chest wall masses.

When the histopathological distribution was considered, it was found that masses which had benign cartilaginous origin (n=12) were chondroitin (n=7, 58%), chondrosarcoma (n=2, 17%), fibrous dysplasia (n=2, 17%), and chondromyxoid fibroma (n=1, 8%). However, the masses which had benign bone origin (n=6) were osteochondroma (n=5, 83%) and giant cell tumor (n=1, 17%). With regard to masses having benign soft tissue origin (n=36), we discovered that those were lipoma (n=12, 33%), nonspecific abscess (n=6, 17%), fibrolipoma (n=6, 17%), tuberculosis abscess (n=4, 11%), ganglioneuroma (n=2, 6% ), leiomyoma (n=2, 6%), hydatid cyst (n=2, 6%), cystic hygroma (n=1, 3%), and hemangioma (n=1, 3%). In addition, the masses having malignant cartilage origin (n=11) were chondrosarcoma (n=11, 100%), the masses which had malignant bone origin (n=16) were osteosarcoma (n=16, 100%), and the masses that had malignant soft tissue origin (n=5) were liposarcoma (n=1, 20%), malignant fibrous histiocytoma (n=1, 20%), leiomyosarcoma (n: 1, 20%), plasmacytoma (n=1, 20%), and lymphoma (n=1, 20%), respectively (Table 3).

| Benign | Number | % | Malignant | Number | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cartilage tissue (bening/malignant: 12/11) | Chondroma | 7 | 58 | Chondrosarcoma | 11 | 100 |

| Chondroblastoma | 2 | 17 | ||||

| Fibrous dysplasia | 2 | 17 | ||||

| Chondromyxoid fibroma | 1 | 8 | ||||

| Bone tissue (bening/malignant: 6/16) | Osteochondroma | 5 | 83 | Osteosarcoma | 16 | 100 |

| Giant cell tumor | 1 | 17 | ||||

| Soft tissue (bening/malignant: 36/5) | Lipom | 12 | 33 | Liposarcoma | 1 | 20 |

| Nonspecific abscess | 6 | 17 | MFH | 1 | 20 | |

| Fibrolipoma | 6 | 17 | Leiomyosarcoma | 1 | 20 | |

| Tuberculosis abscess | 4 | 11 | Plasmacytoma | 1 | 20 | |

| Ganglioneuroma | 2 | 6 | Lymphoma | 1 | 20 | |

| Leiomyoma | 2 | 6 | ||||

| Hydatid cyts | 2 | 6 | ||||

| Cystic hygroma | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Hemangioma | 1 | 3 |

Table 3. Distrubations histopatologic of chest wall masses

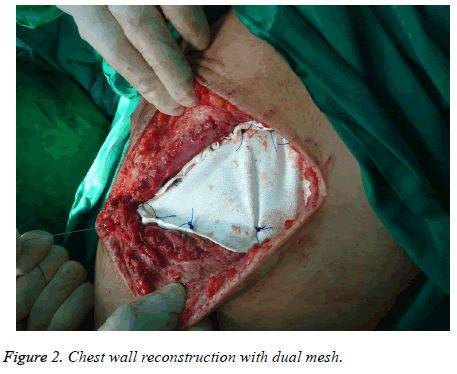

It was found that 13 (15%) of the patients underwent incisional biopsy and medical treatment, 73 (85%) were performed surgical excision and/or drainage, 6 patients (7%) underwent tube thoracostomy, 12 (14%) got muscle flaps, 12 (14%) were applied synthetic grafts (mesh) and 2 patients (2%) were reconstructed with myocutaneous flaps (Figure 2).

Morbidity rate was 8 (9%) and mortality was 2 (2%). The most common complications were respiratory failure and paradoxical motion after sternum resection (n= 1, 1%), empyema (n=1, 1%), wound infection (n=2, 2%), hematoma after surgery (n=2, 2%), and delayed wound healing (n=2, 2%). The average length of stay was 8.5 ± 3.11 days.

Discussion

Chest wall tumors are divided into 3 as malignant, benign and neoplastic. While local invasion of metastasis and adjacent organ tumors constitutes the majority of the chest wall masses, primary chest wall tumors generate 5% of all thoracic neoplasms, and 1-2% of all primary tumors [1].

Primary malignant tumors are derived from the soft tissue, bone and cartilage structures [2]. Most of the malignant tumors are sarcoma-carcinoma metastases of organs or local invasion of adjacent organ tumors such as lung, pleura, mediastinum, and breast tumors [3]. In our study, 41 (48%) of the masses were originated in soft tissue, 23 (27%) were in cartilage, and 22 (25%) had bone tissue origin. From those, the number of patients with benign cartilaginous mass origin was 12 (14%), the number of patients with benign bone mass origin was 6 (7%), the number of patients with benign soft tissue mass origin was 36 (42%), while the number of patients with malignant cartilage mass origin was 11 (13%), the number of patients with malignant bone mass origin was 16 (18%), and the number of patients with malignant soft tissue mass origin was 5 (6%).

The incidence of malignancy in primary chest wall tumors has been reported as 50-80%. In soft tissue tumors, this ratio is higher than that of bone and cartilage tumors [5]. 50% of primary malignant chest wall tumors which develop in bone and cartilage structures are seen in ribs, 30% is seen in the scapula, 20% occurs in the sternum and clavicle [4]. It is maintained more frequently in corpus sternum, manubrium and clavicle [8]. Primary malignant chest wall tumors which develop in soft tissue settle evenly across all locations [4]. In this study, the number of the patients with benign chest wall masses was 54 (63%), while the number of patients with malignant masses was 32 (37%). Malignancy rate of masses developing in cartilage tissue was 48%, in bone tissue was 73%, and in soft tissue was 12%. The most common malignant mass with cartilage origin was chondrosarcoma while the most common malignant mass with bone origin was osteosarcoma.

Primary chest wall tumors are two times more common in males than females. The ages when benign chest wall tumors are seen are 14 years earlier than that of malignant tumors. In other words, the average age for benign tumors was 26, while it was 40 for malignant tumors [9]. In our study, we found that the number of male patients was 56, the number of female patients was 30, and the rate was found to be 1.86.

Chest wall tumors can subcutaneously be asymptomatic as well as swelling, pain, ulcers and infections [4]. Tumors arising from soft tissue are usually painless masses. The tumors developing from the bone causes pain due to periosteal involvement or stress. In those tumors the pain can be the first symptom. The fast-growing lesions are more likely to cause pain and often an indicative of malignancy [2]. All of malignant tumors can gradually be painful. However, twothirds of benign tumors are usually painful [1,5,9]. In some cases, painless palpable masses can be seen in X-rays. Some tumors can be seen with systemic laboratory findings such as fever, leukocytosis and eosinophilia [1]. In our study, the main symptoms are painless swelling (n = 51, 59%), painful swelling (n=35, 41%), cough (n=11, 13%), dyspnea (n=9, 10%), fever (n: 9, 10%), pleural effusion (n=6, 7%), and nausea - vomiting (n=4, 5%).

A detailed history and physical examination are required for diagnosis. If the patient has a history of malignancy, some risk factors for soft tissue or bone sarcoma can be present. The first radiological examination for diagnosis is chest X-ray. Computed tomography (CT) is the most effective imaging method in the diagnosis of chest wall tumors. It is useful in showing masses developing from ribs, damaging bone cortex, and calcifications within the mass and lung metastases. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays an integral role in the diagnosis and treatment plan. It effectively shows soft tissue involvement, bone marrow infiltration, intraspinal spread of tumor and relation to mediastinal structures. Positron emission tomography (PET-CT) is an effective method for assessing the spread of tumors, especially sarcoma of the biological heterogeneity, tumor staging and response to treatment [2]. In our study, the main methods used for diagnosis were chest X-ray, CT scanning, MRI, PET-CT, needle aspiration, tru-cut biopsy, incisional and/or excisional biopsy. However, chest X-ray and CT were the majority.

The most common benign tumors of the chest wall are osteochondroma, chondroma, fibrous dysplasia and eosinophilic granuloma. Osteochondroma constitutes 50% of all benign rib tumors. It originates from the metaphyseal region of rib. Calcification in the periphery of mass can radiologically be visible. Tumors occur in childhood, and will continue to grow until full maturation of the skeletal system. For osteochondomatosis after puberty and in adulthood, resection is recommended. If asymptomatic mass detected before puberty becomes symptomatic or starts to grow, resection should be conducted by interpreting in favor of malignant degeneration [1,4]. In our study, the most common bone mass was osteochondroma (n=5, 83%).

Chondromas are one of the most common tumors of the chest wall. It usually develops in costochondral junction in the anterior chest wall. It can be seen at any age. It is usually a slow-growing mass, and can be painful. It gives an expansive mass image which radiologically depletes the bone cortex. In addition, its appearance may be lobular. On the other hand, it is impossible to distinguish chondroma and chondrosarcoma clinically and radiologically. Moreover, it can be very difficult to distinguish between chondroma and chondrosarcoma microscopically. Therefore, chondromas should be treated similar to malignant tumors, and a wide resection should be conducted [4,5]. In our study, the most common mass of cartilage tissue was chondroma (n=7, 58%).

Fibrous dysplasia occurs as a painless, asymptomatic mass in young adults. It often develops from the posterior rib. There is no history of trauma. In fibrous dysplasia, it is radiologically observed that the cortex becomes thinner and central fusiform expansions free from calcification occur [9]. Resection is not necessary in asymptomatic cases. In most cases, the growth of lesions stops after puberty. Surgical resection is recommended for patients in whom the growth of mass continues and becomes painful [1,4]. In our study, fibrous dysplasia rate was 17% (n=2).

Chondrosarcoma is the most common primary malignant bone tumors of the chest wall. It is usually located on the anterior chest wall. To become more specific, 80% is located in the rib, and 20% is located in sternum. It may be developed with the malignant degeneration of benign chondroma. In some of the cases, a history of trauma is present in mass location [1]. It usually has a slow-growing painful character. It is radiologically seen as a lobular mass which grows in the medullary part of rib or sternum and destructs cortex. As it is impossible to distinguish chondroma and chondrosarcoma radiologically, a histological examination is required for proper diagnosis of malignancy. Chondrosarcoma is seen as a mass which includes chondrocyte type calcifications, significant soft tissue components and expanses the bone structure [2]. However, a well-differentiated chondrosarcoma is histologically difficult to distinguish from chondroma. Therefore, wide resection should be applied to all tumors arising from the costal cartilages [5]. The treatment of chondrosarcomas is wide resection with 4 cm margin and reconstruction. Chemotherapy is ineffective. However, radiotherapy, although it is not very effective, can be applied in cases surgical resection cannot be conducted and surgical limit is positive. In a series which was published in Mayo clinic, the 5-year survival rate was reported as 92% [10]. If surgical resection is not wide enough, it may locally be recurred and the survival rate can significantly reduce. Because of local recurrence in later periods, chondrosarcoma requires long-term follow-up [9]. In our study, the number of patients diagnosed with chondrosarcoma was 11.

Some chest wall tumors such as plasmacytoma and osteosarcoma are initially treated better through non-surgical methods. Therefore, the diagnosis of tissue is an important step for creating the treatment algorithm of chest wall tumors [11]. There are two important issues to be considered when sampling for tissue diagnosis. The first one is that the area of biopsy should remain in subsequent surgery area. The second, the flaps which will probably be used should not be damaged. There are 3 sampling alternatives are available for tissue diagnosis; needle biopsy, incisional biopsy and excisional biopsy [12]. In our study, the number of patients diagnosed with osteosarcoma was 11, while the number of patients with plasmacytoma was 1.

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy is not preferred in the diagnosis of primary bone or cartilage tumors. It is usually used to evaluate the chest wall metastasis of a known malignancy [5]. The success rate of percutaneous needle biopsy in the diagnosis of musculoskeletal tumors has been reported as 92% [2,13-15]. Incisional biopsy is the ideal choice for the diagnosis of the primary chest wall tumors which is greater than 5 cm and cannot be diagnosed by needle biopsy. Incisions should be planned considering the surgery to be conducted later. With the aim of diagnosis, excisional biopsy with 1 cm margin can be performed to the tumors which are smaller than 5 cm. If benign tumor is diagnosed or a malignancy that requires the application of medical treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both) is identified, additional surgical intervention is not necessary. If the primary malignant tumors are diagnosed, a second surgery including radical excision with wide margins is performed. Moreover, reconstruction is applied when necessary [1].

An incisional biopsy is preferred in cases where tumors which have metastatic or hematologic origin and extensive surgical resection cannot be performed. Due to the difficulty in differentiating preoperative and intraoperative benign and malignancies in bone and cartilage-induced tumors, resection should be done in a wide and secure line. Therefore, reconstruction is necessary after resection. In patients with malignant masses, clinical symptoms, the diameter, and the age of the patient are higher [16]. Treatment varies from surgical resection and reconstruction to multimodality treatment consisting of chemotherapy and radiotherapy [14,15]. In the majority of chest wall tumors, wide surgical resection is the most effective treatment. With the help of diagnostic imaging methods, the advances in reconstruction techniques and perioperative care, chest wall resection can be performed with low morbidity and mortality. In addition, excellent functional and cosmetic results can be obtained through the use of a variety of prosthetic materials, muscle flaps and free tissue flaps [4,11]. Patients can be successfully treated with correct diagnosis, wide resection and appropriate reconstruction of major defects. In our study, 13 (15%) of the patients underwent incisional biopsy and medical treatment, 73 (85%) were performed surgical excision and/or drainage, 6 patients (7%) got tube thoracostomy, 12 (14%) were performed muscle flaps, 12 (14%) got synthetic grafts (mesh) and 2 patients (2%) underwent reconstruction with myocutaneous flaps.

Conclusion

Primary-secondary chest wall tumors require a multidisciplinary approach. Biopsy methods should be carefully selected, and resection should be performed in a wide and secure line. Even if the lesion is malignant, successful treatment and long-term survival depend on the complete resection which is sufficient in diameter. In this way, lower morbidity and mortality rates can be achieved.

References

- Park BJ, Flores RM. Chest wall tumors. In: General Thoracic Surgery, Lippincott Williams&Wilkins. Philadelphia 2005.

- Refaely Y (Çeviren: Bostanci K). Gögüs Duvari ve Sternum Tümörleri-genel Bakis. In: Eriskin Gögüs Cerrahisi (Adult Chest Surgery), Nobel Tip Kitapevileri, Istanbul 2011.

- Pairolero PC, Arnold PG. Chest wall tumors. Experience with 100 consecutive patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1985; 90: 367-372.

- Toker A, Kalayci G, Gögüs duvari ve sternum tümörlerinde cerrahi tedavi. In: Gögüs Cerrahisi. Bilmedya Grup, Istanbul 2001.

- Pairolero PC. Chest wall tumors. In: Sabiston & Spencer Surgery of the Chest Elsevier Saunders. Philadelphia 2005.

- Adkins PC. Tumors of the chest wall. In: General Thoracic Surgery, Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia 1983.

- Fisher RA. On the interpretation from contingency tables, and the calculation of P. J Royal Stat Soc 1922; 85: 87-94.

- Fontaine JP, Lukanich JM. (Çeviren: Bostanci K). Dternal ve Klaviküler Gögüs Duvari Rezeksiyonu ve Rekonstrüksiyonu. In: Eriskin Gögüs Cerrahisi (Adult Chest Surgery), Nobel Tip Kitapevileri, Istanbul 2011.

- Graeber GM, Jones DR, Pairolero PC. Neoplasms of the chest wall. In: Pearson's Thoracic & Esophageal Surgery. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier Inc. 2008; 1291-1302.

- Fong YC, Pairolero PC, Sim FH, Cha SS, Blanchard CL. Chondrosarcoma of the chest wall: a retrospective clinical analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004.

- Jones DR (Çeviren: Bostanci K). Gögüs Duvari Rezeksiyonu ve Rekonstruksiyonu. In: Eriskin Gögüs Cerrahisi (Adult Chest Surgery), Nobel Tip Kitapevileri, Istanbul 2011.

- Muhammedtaheri Z, Dorudinia A, Daneshvar A, Azar PA, Mohammadi F. Histologic Types of Chest Wall Tumors-Nine Years’ Single Center Experience Open J Pathology 2014.

- Welker JA, Henshaw RM, Jelinek J, Shmookler BM, Malawer MM. The percutaneous needle biopsy is safe and recommended in the diagnosis of musculoskeletal masses. Cancer 2000; 89: 2677-2686.

- Yamaguchi U, Chuman H. Surgical Treatment of Primary Bone Chest Wall Tumors. JSM Clin Oncol Res 2014; 2: 1017.

- Çiledag N, Arda K, Aktas E, Aribas BK. Primer Gögüs Duvari Tümörleri. Turkish Med J 2010; 4: 65-70.

- Tukiainen E. Chest wall reconstruction after oncological resections. Scand J Surg 2013; 102: 9-13.