Review Article - Journal of Public Health and Nutrition (2018) Volume 1, Issue 2

An analysis of the impact of reference groups on collectivist families' meal social interaction behaviour in Sierra Leone.

Sheku Kakay*Department of Management, Leadership and Organisation, Hertfordshire Business School, University of Hertfordshire, United Kingdom

Accepted date: May 02, 2018

Citation: Kakay S. An analysis of the impact of reference groups on collectivist families’ meal social interaction behaviour in Sierra Leone. J pub health catalog. 2018;1(2):41-52.

DOI: 10.35841/public-health-nutrition.1.2.41-52

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Public Health and NutritionAbstract

Background: Reference groups predominantly shapes the meal social interaction behaviour of most Sierra Leonean families as it is designed to orient their thinking about the symbolic role of hierarchy and authority, which help define the character of children as they grow-up and teaches them responsibility. The re-shaping and streamlining of the family members’ character help foster a better relationship between them and promotes closer ties even with external relations, neighbours and others within the community. In addition, it significantly helps the family to plan its food purchase and consumption habits, which prevents them from experiencing food scarcity. However, reference groups impinge on the effective use of resources and food distribution in the family, which limits their ability to access variety, quality and adequate food. The differences in cultural backgrounds between family members and their extended relations impacts on the family negatively in terms of thieving, divulging of family secrets, backbiting and most significantly breeding jealousy and nepotism. This paper, therefore, critically evaluates the impact of reference groups on collectivist families’ meal social interaction behaviour in the Sierra Leonean context. Methods: The researcher used one-to-one semi-structured qualitative interviews to investigate families’ views and experiences of their mealtimes’ behaviours. In this research, due to the fact that the selected samples of families were unknown, the researcher used snowballing; convenience; and experiential sampling in recruiting respondents, including males and females from different cultural, ethnic, religious and professional backgrounds, across the different regions of Sierra Leone. The interviews were guided by a topic, and this procedure was followed until no new themes emerged. The interviews were recorded using an audio recorder, which were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using a thematic approach

Results: Twenty families (comprising 20 husbands and 20 wives) with a sample size of 40 participants were interviewed in this study. The paper highlights the influence of reference groups on the behaviour of Christian and Muslim families (husband and wife) at mealtimes and draw attention to its significance as influencer of collectivism, particularly in relation to its impact on the social interaction between similar and dissimilar gender groups. The author critically analyzed the influence of reference groups on families’ meal social interaction behaviour and presents a comparative summary of how gender affects the meal behaviours of different gender and religious groups.

Conclusion: This study suggests that reference groups play a key role in influencing families’ behaviour at mealtimes, which espouse positive and negative effects on their meal social interaction behaviours. To capture its symbolism among the different social groups, the author critically reviewed and presented a comparative analysis of the similarities and differences in behaviour between and across gender and religious groups.

Abstract

Background: Reference groups predominantly shapes the meal social interaction behaviour of most Sierra Leonean families as it is designed to orient their thinking about the symbolic role of hierarchy and authority, which help define the character of children as they grow-up and teaches them responsibility. The re-shaping and streamlining of the family members’ character help foster a better relationship between them and promotes closer ties even with external relations, neighbours and others within the community. In addition, it significantly helps the family to plan its food purchase and consumption habits, which prevents them from experiencing food scarcity. However, reference groups impinge on the effective use of resources and food distribution in the family, which limits their ability to access variety, quality and adequate food. The differences in cultural backgrounds between family members and their extended relations impacts on the family negatively in terms of thieving, divulging of family secrets, backbiting and most significantly breeding jealousy and nepotism. This paper, therefore, critically evaluates the impact of reference groups on collectivist families’ meal social interaction behaviour in the Sierra Leonean context.

Methods: The researcher used one-to-one semi-structured qualitative interviews to investigate families’ views and experiences of their mealtimes’ behaviours. In this research, due to the fact that the selected samples of families were unknown, the researcher used snowballing; convenience; and experiential sampling in recruiting respondents, including males and females from different cultural, ethnic, religious and professional backgrounds, across the different regions of Sierra Leone. The interviews were guided by a topic, and this procedure was followed until no new themes emerged. The interviews were recorded using an audio recorder, which were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using a thematic approach

Results: Twenty families (comprising 20 husbands and 20 wives) with a sample size of 40 participants were interviewed in this study. The paper highlights the influence of reference groups on the behaviour of Christian and Muslim families (husband and wife) at mealtimes and draw attention to its significance as influencer of collectivism, particularly in relation to its impact on the social interaction between similar and dissimilar gender groups. The author critically analyzed the influence of reference groups on families’ meal social interaction behaviour and presents a comparative summary of how gender affects the meal behaviours of different gender and religious groups.

Conclusion: This study suggests that reference groups play a key role in influencing families’ behaviour at mealtimes, which espouse positive and negative effects on their meal social interaction behaviours. To capture its symbolism among the different social groups, the author critically reviewed and presented a comparative analysis of the similarities and differences in behaviour between and across gender and religious groups.

Keywords

Collectivism/Individualism, Reference groups, In-group/Out-group, Social interaction, Consumer behaviour

Background

Reference groups, in the Sierra Leonean context, have predominantly influenced individuals’ collectivist behaviours over the years and will continue to do so in the future, though discrepancy still exists among various theorists about their degree of influence [1,2]. Lawan et al. Ayoko et al. pointed to the tendency of focusing on group preferences and group harmony in collectivist cultures, which leads to the opportunity of suppressing internal (personal) attributes in certain settings [3,4]. Abraham et al. and Bolten argued that, kinship networks are extremely important in the everyday matters of Sierra Leonean families, and that one is obliged to assist one’s family members throughout life [5,6]. Accordingly, most people in Sierra Leone abide by the collectivist cultures because of the limited opportunity that exists in terms of jobs and other social amenities and therefore drive the collectivist tendency upwards to enhance the survival of close families, in-groups and/or kinship network. This collectivistic tendency is evident in almost all ethnic groups within Sierra Leone; except for a few people who are well educated and have attained certain social status in society employ the British or American individualistic orientations [7].

In Sierra Leone, whose culture is predominantly collectivist; the idea of accommodating extended family values is not uncommon-with one large joint family unit living together under the same roof with a single breadwinner. A number of theorists re-affirmed this argument and that the basic household structure of Sierra Leone is an extended family, organized for the majority of people around the farm and its rice production [8,9]. Chinunda reiterated that many households are polygamous, where a husband may have more than one wife; the first or "senior" wife usually has some authority over "junior" wives, such as in training and organizing them into a functional unit [10]. However, Manyama also proclaimed that monogamy is also common, especially among urban and Christian families [11]. Akin to this view, Sanchez-Sosa et al, Amato and Epstein suggested that the extended family provides a very different type of environment for interaction among members as there are multiple sources of influences based on interaction and observation of others, and the family members are considered as of greater importance than outsiders [12-14]. This evidence is glaring in the Sierra Leonean culture, where most family members show a high degree of commitment and loyalty for people of the same descendants/in-groups. However, as the generational link expands beyond two generations, the level of commitment, loyalty and unity declines, which can be largely attributed to acculturation [15-17].

The degree of influence of reference groups, particularly extended families on families’ meal social interaction behaviour in the African context is yet to be firmly established, as there is a lack of empirical data/evidence to substantiate the claim. A number of theorists, for example, Attah et al., Daya et al. and Horner et al, affirmed that the concept and impact of extended families or reference groups on the food consumption behaviour of people in the African continent is yet to be fully studied [18-20]. They emphasized that, most literature on consumer behaviour focused either on the United States, United Kingdom and other European countries or on China, Japan and other Asian countries. It is against the backdrop of these arguments that the researcher evaluated the impact of reference groups on families’ meal social interaction behaviour in the Sierra Leonean collectivist context.

Methods

The researcher conducted one-to-one semi-structured face-toface qualitative interviews with families about the reference group factors that influenced their meal social interaction behaviour. This allowed families from different ethnic, religious and cultural backgrounds, based on their perspective and own words elucidate their views of the reference group attributes that influences their meal social interaction behaviours. The researcher during the semi-structured interviews introduced a theme and allowed the conversation to develop according to cues taken from what respondents said about their families.

Participants and recruitment

The researcher used snowballing; convenience; and experiential sampling to recruit families from different ethnic and religious (Muslim and Christian) backgrounds from across the four regions of Sierra Leone, including the northern, southern and eastern provinces as well as the western area. The researcher primarily focused on urban areas, particularly the provincial headquarter towns with about 20% of the families selected in the North (Makeni), 20% in the South (Bo), 20% in the East (Kenema), and 40% in the Western area (Freetown). This implies that, 4 families were recruited in the North (Makeni), 4 in the South (Bo), 4 in the East (Kenema), and 8 in the Western Area (Freetown). A Sample representation and demographic information of families, who participated in the face-to-face semi-structured interviews, are presented in the Table 1. A total of 20 families (20 husbands and 20 wives), a sample size of 40, from various households were contacted across the country with a vivid explanation given to them about the study including potential risks of data publication, benefits to the country generally, and the assurance of confidentiality. The main participants in the study were husbands and wives (married couples) from different ethnic and religious backgrounds. The researcher ensured that an equal religious representation was selected for the interviews with ten families from each of the denominations (Muslim and Christian). The husbands and wives were interviewed separately to avoid any biasness or to prevent one couple influencing the other. Consequently, twenty families (20 husbands and 20 wives) were interviewed with 50% from each denomination (Muslim and Christian). Initial appointments and participant invitation letters; the research themes to be covered; and the participant information sheet detailing the interview protocol, commitment, benefits; and risks and confidentiality were issued to the interviewees at their various places of work before the official scheduled interviews at their homes.

Interviews

A guideline was developed for the entire research process, which was followed from the planning phase onto the implementation phase of the research to avoid any incongruity in the research process. The analysis of literature, guided the identification of theories and ideas that were tested using the data collected from the field. This was done in the form of a gap analysis. The researcher used open-ended questions and themes, from which a broad conclusion was drawn. The themes included Age, gender, associates/social relations, decision-making, ethnic group, friends/neighbours/family members, family image, extended family, identity. The interview for each respondent was scheduled for an hour, but on the average, it lasted between 50 and 55 minutes. The researcher carried out the interviews at the homes of the interviewees with the conversations recorded on a digital audio recorder.

Data analysis

The researcher transcribed all the data verbatim and imported them into NVIVO 10 to facilitate the analysis and coding. An iterative approach of reading and rereading the transcripts, identifying themes and patterns, and comparing across the data was used in analyzing the data. Thus, continuity in the coding process helped identify redundancies and overlaps in the categorization of the scheme, and then grouped both sequentially and thematically. The use of NVIVO 10 facilitated the development of an audit trail through the use of memos, providing evidence of confirmation of the research findings. After collating and coding, the data was summarized and organized by comparing the responses provided by the different family (husband and wife) members, and conceptualized the interpretation of each category by each family member, and how they interact with each other. The researcher noted that sometimes, there were variations in responses from different family members, which could have prompted the use of more than one code, which resulted in the building up of different sub-categories. The researcher worked on the categorization scheme, assignment of codes, and interpreted and reviewed the transcripts independently. Where there were differences in interpretations, commonalities and differences were identified and interpreted appropriately. Therefore, the researcher used triangulation to enhance the credibility of the data. Also, the audio-recordings and associated transcripts (field notes) were transcribed as soon as the researcher returned from the field to avoid unnecessary build-up of information and data and avoid loss of vital information.

Results

The researcher used a sample of 40 respondents, who were between the ages of 18 and 65 years, as participants in the one-to-one semi-structured face-to-face interview. A tabular representation of the sample and personal data of the respondents are depicted in Table 1. The researcher considered the husband and wife (married couples) in each family as the main participants in the interview process. About twenty families (20 husbands and 20 wives) were selected in order to get a balanced response and interpretation of the results, and to reduce biasness to the bare minimum. A tabular summary of the degree of predominance of the reference group factors that influenced families’ meal social interaction behaviour are depicted in Table 2. It was imperative that, after the twentieth family, the data was saturated as the information collected from the 18th, 19th and 20th families (35th, 36th, 37th, 38th, 39th and 40th interviewees) were similar to those stated by earlier respondents.

| Families | Demographic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Family 001 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: procurement office |

| Ethnicity: Creole | |||

| Family size: 3 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Banker | |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 3 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Family 002 | Wife | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Businesswoman/self-employed |

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Constructor | |

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Family 003 | Wife | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Nurse |

| Ethnicity: Yalunka | |||

| Family size: 12 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Teacher | |

| Ethnicity: Kono | |||

| Ethnicity: Yalunka | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||

| Family size: 12 | |||

| Family 004 | Wife | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Geologist |

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||

| Family size: 7 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Banker | |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 7 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Family 005 | Wife | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Businesswoman/self-employed |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Police Officer | |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Family 006 | Wife | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Teacher |

| Ethnicity: Kono | |||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Civil servant | |

| Ethnicity: Kissy | |||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Family 007 | Wife | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Businesswoman/self-employed |

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Finance Officer | |

| Ethnicity: Kono | |||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Family 008 | Wife | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Social worker |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 10 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Social worker | |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 10 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Family 009 | Wife | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: mid-wife |

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Businessman/self-employed | |

| Ethnicity: Madingo | |||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Family 010 | Wife | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Teacher |

| Ethnicity: Koranko | |||

| Family size: 10 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Civil engineer | |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 10 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Family 011 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Teacher |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Civil servant | |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Family 012 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Teacher/Pastor |

| Ethnicity: Limba | |||

| Family size: 6 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Lecturer | |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 6 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Family 013 | Wife | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Nurse |

| Ethnicity: Creole | |||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Lecturer | |

| Ethnicity: Limba | |||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Family 014 | Wife | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Teacher |

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Agricultural Officer | |

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP3 | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Family 015 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: University Administrator |

| Ethnicity: Creole | |||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: University Administrator | |

| Ethnicity: Creole | |||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Christianity | |||

| Family 016 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Principal |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Deputy Director (Civil Servant) | |

| Ethnicity:Yalunka | |||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Family 017 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Businesswoman/Self-employed |

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||

| Family size: 9 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Medical Lecturer | |

| Ethnicity: Fullah | |||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Family 018 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Teacher |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Businessman/self-employed | |

| Ethnicity: Madingo | |||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Family 019 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Housewife |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 12 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Civil servant (Deputy Director General) | |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 12 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Family 020 | Wife | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Social worker |

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||

| Family size: 3 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

| Husband | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Social worker | |

| Ethnicity: Madingo | |||

| Family size: 3 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||

| Religion: Muslim | |||

Table 1: Sample representation and demographic information of families who participated in the face-to-face semi-structured interviews.

| Reference Groups | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Respect | Predominant in all families |

| Hierarchy | Predominant in all families | |

| Wisdom | Emphasised by a majority (CM, MM, MF), but less by CF | |

| Authority/guidance | Predominant in all families | |

| Experience | Emphasised by a majority of Muslims only (MM, MF) | |

| Gender | No impact | Predominant in all families |

| Gender distinction | Predominant in all families | |

| Associates | Idea sharing | Emphasised by a majority (CM, CF, MF), but less by MM |

| Regulation/control | Emphasised by a majority of females regardless of religion (CF, MF) | |

| Building relationship | Predominant in all families | |

| Decision-making | Planning | Predominant in all families |

| Authority/hierarchy/guidance/control | Emphasised by a majority (CM, CF, MM), but less by MF | |

| Development | Emphasised by a majority of MF only | |

| Family unity/stability | Emphasised by a majority of females regardless of religion (CF, MF) | |

| Extended families | Background differences | Predominant in all families |

| Economic/financial constraints | Emphasised by a majority (CF, MM, MF), but less by CM | |

| Domestic chores | Emphasised by a majority of Muslims only (MM,MF) | |

| Identity | Position/rank | Predominant in all families |

Table 2: A Summary of the reference groups factors that influenced families’ meal social interaction behaviour.

Key findings of the study

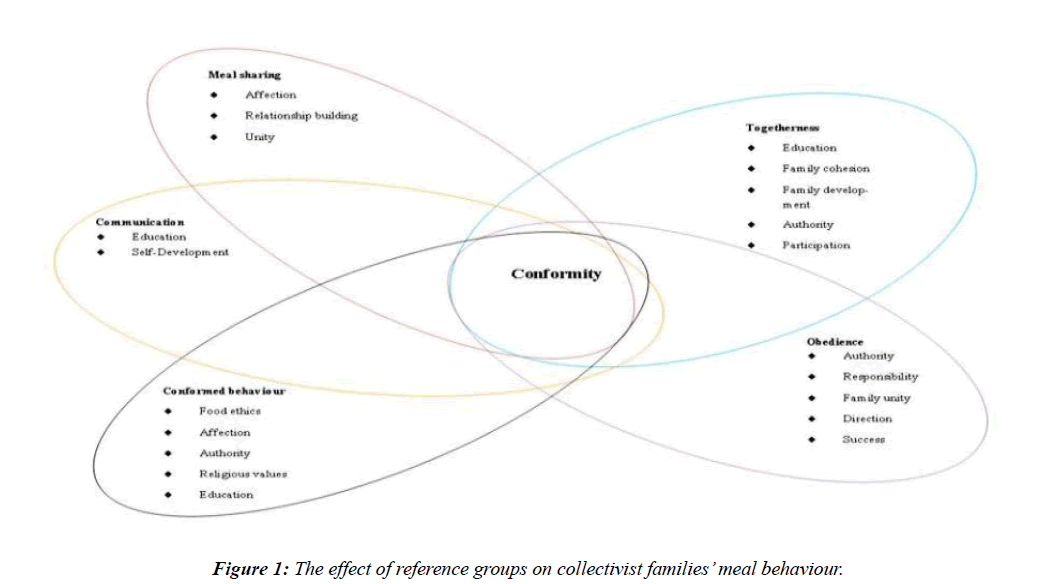

The analysis of this study identified a number of themes and sub-themes, as key reference group influencers of families’ meal social interaction behaviour, including age, gender, decision-making, associates, extended family and identity. A comprehensive evaluation and discussion of the influence of each sub-groups on participating males and females was undertaken. The themes and sub-themes that emerged from the study are depicted in the Table 3 and the Figure 1 below:

| Interviews with Families | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature | Questions | Field themes | Field sub-themes |

| Reference Groups | How important is age in your family’s social interaction at the dinner table? | Hierarchy | Position, ranking, expectations, respect (MW, CW, MH, CH), obedience, roles, maturity, responsibility, assistance, contribution (MH), Preference, seniority, maturity (CW), family head, elderliness, hierarchy (MW, CW, MH, CH) |

| Authority | Shapes behaviour, control behaviour, boundaries, peace/harmony (MW, MH), command, love (CW), protection (CW, MH), rules, regulations, understanding/tolerance (CW, MH), unity/stability (MH), authority (MW, CW, MH, CH), guidance | ||

| Decision-making | Wisdom (MW, CW, MH, CH), experience (MW, CW, MH), advice (MW, MH), information /communication (MH), responsibility, learning (MW), commonality, direction, contentment (MH), success (MH), decision-making (MW, MH, CH), blessing (MH), values (CH), affection (CH), participation (CH) | ||

| Why does gender influence the way your family interact socially at the dinner table? | Task distribution | Domestic chores, role definition (MW, MH, CH), responsibility, food quality (CH) | |

| Gender distinction | Eating boundaries (MW, CW), position, breadwinner (MW), food quality, respect, food preparation, male supremacy, (MW), learning (MW), gender distinction (MH, CH), gender separation (MH, CH), authority (MH, CH), respect (CW, MH) | ||

| In what ways does the importance of associates influence your family’s interaction at the dinner table? | Control/regulation | Guidance (CH), correct behaviour, direction, shape behaviours, behaviour improvement, rules, identity (MH), politeness (MH), control/regulation (MW, CW, MH), respect (MW, CW, MH) | |

| Education | Solution, cultural learning, social etiquette, advice (MW, CH), idea sharing/education (MW, CW, MH, CH), civility (CW), table manners, idea generation, values (CH), beliefs, social learning, family history (MH), knowledge sharing, training, troubleshooting (MW, CH) | ||

| Affection | Understanding, bonding, love/affection (MW, CW, MH), care, social relationship/building relationship (MW, CW, MH, CH), unity/stability (MW, CW, CH), closeness, togetherness, happiness, help, trust, meal sharing (MW, MH), socialization (CH), connectivity, family image (MH), compassion, oneness, sympathy, cordiality, sense of belonging, prayer (CW), expectation (CW), blessing (CW), participation (CH) | ||

| Social/economic costs | "Resource overburden (MW, MH), conflict (MW, CW), thieving (CW), anti-social behaviour" | ||

| How important is decision-making in your family’s social interaction at the dinner table? | Planning | Guidance, direction (CW, MH), family interest, development (MW, CW, MH, CH), right path, solution, growth, prioritisation (MW), idea generation, character moulding, responsibility, family safety, consultation (MW, CW, MH, CH),learning (MH, CH), reduce wastage (MH), consent (MH), achievement (MH), choices (MH), right track, organising(MW, MH), management/coordination (MH), view sharing, prosperity/progress/success (MW, CW), rationality (CH), projection, conscientiousness, judgement (CH), planning (MW, CW, MH, CH), task distribution (CW), collaboration (CH) | |

| Family cohesion | Unity/cohesion/stability (MW, CW, CH), peace/tranquility (MW),happiness, love, understanding (MH, CH), relationship building, harmony (CW, MH),equality (MH), fairness, togetherness, socialisation, collaboration, collectiveness, care (MW), participation (CW), family image (MH) | ||

| Hierarchy/authority | Respect (MW), shape behaviour, authority/control/guidance (MW, CW, MH, CH), maintain order, age (MW), seniority, role definition, discipline (CW), orderliness, correct behaviour, rules, obedience (MH, CH), family head, command, dictatorship, listening, regulation, contribution (CH), responsibility (CW), safeguards (CW), democracy (CH) | ||

| How do extended family members affect your family’s meal social interaction behaviour? | Economic costs | Economic and financial constraints (MW, CW, MH), Resource, expenditure, food quantity, food quality | |

| Social costs | Gossip, different background (MW, CW, MH, CH), cultural variation, divulge family secret (MW, CW, MH), breed hatred (MW, CW, MH), stealing/thieving (MW, CW, MH, CH), witchcraft/evil spirit (MW, MH), quarrels, conflict/misunderstanding (MW, CW, MH, CH), envy, feud, animosity, jealousy/comparison (MW, CW, MH, CH), stalls development (MH, CH), ostracisation (MH), bullying (CH), obligatory (MH, CH), misunderstanding, backbiting/gossip (MW, CW, MH), behavioural challenges (MH), malice (MH) | ||

| Social benefits | Sharing (MW, CW, MH), domestic chores (MW, CW, MH, CH), advice (MW), shape behaviour, lineage knowledge (CW), bonding (MH), reduce workload, Domino effect (MH, CH), love, share ideas, cordiality, subsidise income (MH), appreciation, gifts (CH), gratification/gratification (CH), charitable act (MH), cultural beliefs (MH) | ||

| What is your opinion of the definition of identity within the family when interacting at the dinner table? | Authority/hierarchy | Position/rank (MW, CW, MH, CH), control (MW, CW, MH), respect (MW, MH, CH), roles/responsibilities (MW, MH, CH), boundaries, seniority, shape behaviour, priority (MH), age (MH), headship, obedience (MH), guidance, Orderliness (CH), law and order, right and wrong (CW) | |

| Family cohesion | Discrimination (MW, CH), togetherness/unity (CW), relationship definition, sense of belonging (CW), love, distinction/differentiation (CW), discord, learning (CH), expectations (MW), boundaries (CW) | ||

Table 3: Thematic Analysis and schematic summary diagrams of the impact of reference groups on families’ meal social interaction behaviour.

The impact of Age on families’ meal social interaction behaviour

Multiple female participants (Muslim and Christian) highlighted respect as fundamental reference group attributes that influences their families’ meal social interaction behaviour. This suggests that age is an essential ingredient for determining the degree of involvement in social interaction at mealtimes, as children should not be involved in adult discussion, as it symbolizes disrespect. Consequently, it has the resultant effect in determining the order of food distribution, and to some extent the quantity of food access by individuals at mealtimes.

“Age is very important as it serves authority and determinant of whom to respect and who not to talk freely to at the dinner table. When an elder is speaking to you at the dinner table, it is important you abide by his/her command. If I am not around, the eldest daughter/son takes responsibility for the entire family and the younger ones must respect her and the orders she gives. Age enables us to determine who is older than the other and determines who should be respected at the dinner table because you cannot ask the elder one to fetch water when the younger is seated at the same table” (Interviewee 5, Female, Christian)

However, Muslim females highlighted the symbolism of authority as fundamental arbiter of age, which was less emphasized by Christian females. They argued that, age define the roles and responsibilities of individuals in a family, and acts as a source of wisdom and experience. This implies that, age is an instrument/tool used by adults to provide appropriate advice and guidance to children at the dinner table, which enables them to discern between rights and wrongs.

“Age is important as it signifies respect, authority, wisdom and experience. In our culture, it is always important to give respect to your elders, whether they are your parents or not. At the dinner table, children are not allowed to talk in the presence of elders as a symbol of respect”. (Interviewee 21, Female, Muslim)

In tandem with the females, an overwhelming number of male participants (Muslim and Christian) identified respect, as critical to their families’ meal social interaction behaviour. They professed that, as a mark of respect, children should not have eye contact with adults at mealtimes, but to concentrate and focus on the food in front of them. It is also fundamentally the responsibility of young ones to hold the dish/plate/bowl in position when eating from a common dish/plate/bowl with elders, and they are responsible for fetching water for washing hands before eating. Adherence to this responsibility, they claimed, can help guide and protect children from making mistakes and pushes them to behave properly in the public.

“Age of course depicts the hierarchy of one’s family and because you are either the father, mother, eldest son/daughter, it is onerous on everybody, especially at the dinner table to respect people that are older than you. In Africa, we respect age a lot and as a family it is paramount that we give credence to age, particularly to people that are older than you. So age is very important as it signifies authority and who should do what in the home” (Interviewee 14, Male, Christian)

The impact of gender on families’ meal social interaction behaviour

Role distinction and gender separation at mealtimes emerged as a primary determinant of families’ meal social interaction behaviour. However, the degree of influence varies between the Muslim and Christian females, as the practice is predominant among Muslim females than their Christian counterparts. Participants who embrace the practice argued that, females are socialized to perform the traditional role of cooking, serving, and cleaning the dining area after eating; whilst males are socialized to perform the role of breadwinners and/or heads of the families. It is fundamentally a normal traditional practice in some families, for males and females to eat separately in groups, as males are socialized and trained to assume leadership roles, whilst females assume subservient roles.

“Well, in my family, we most times eat from a common bowl, and women are only allowed to eat together with women and men are also expected to eat with men. Also, greater attention is given to male children than the female ones because my husband always sees the male children as his future inheritance. He always signals that the women will one day get married and absorbed into another family while the men will always bear his name. So at the dinner table, he gives the male children more attention than the females. Also, the cleaning of the pots, pans and plates are normally done by the females and they are also required to sweep and clean the dinner table before and after eating”. (Interviewee 33, Female, Muslim)

“Well, no, gender has no significance when we are interacting at the dinner table. We have gender equity. We don’t discriminate between our children to say that this is a girl or this is a boy and that they should behave in a specific way at the dinner table”. (Interviewee 15, Female, Christian)

Despite the prevalence of the practice across different ethnic and religious groups, many Muslim and Christian males emphasized that gender has limited impact on their families’ socialization at mealtimes. This is largely due to their exposure to western education and urban acculturation. It is imperative that, the exposure of some families in the urban areas to Western education and urbanization has forced them to renege on traditional practices inherited from their forebears.

“Despite being a Muslim, but my level of education bars me from discriminating my children because I do not even know who will be what later in life. However, in my culture, we expect to women to sit and eat together as a unit and from a common bowl and the men are also expected to eat together from the same bowl. But I don’t encourage that in my family, may be because of my level of education”. (Interviewee 36, Male, Muslim)

The impact of associates on families’ meal social interaction behaviour

Several Muslim and Christian females highlighted associates/ non-family members as significant influencers of their families’ meal social interaction behaviour. Socializing with associates refines the behaviour of the children at mealtimes, as it teaches them how to love others, improves social etiquette, and foster better relation with outsiders. It also helps the children to cultivate the idea of sharing and teaches them the morals of life, as the African culture professed that, “no man is an Island. The perceived value of associates, as proclaimed by many participants, is that they help the family with their domestic chores. They have also been touted to settle family disputes, subsidize family incomes and act as a source of advice to the family. Despite the avowed acknowledgement of their positive impact on families, but a wind of caution advanced by a few participants is that, associates with bad behaviours/characters, including thieving and vulgarity can impact negative on the families’ meal social interaction behaviour.

“Well, like I said earlier, we have a system of shared beliefs and values in my family, wherein we are always open to strangers sharing meal with us at the dinner table irrespective of the background of the visitor. We are always open…it teaches the children the importance of sharing, particularly in Sierra Leone were opportunities are scarce. When God provides for the family it is always important that we share with other people as this will act as blessing to the family…builds an everlasting bond of respect and trust as they will always say good things about your family outside…forum of sharing ideas…” (Interviewee 27, Female, Christian)

In tandem with the female participants, the male participants (Muslim and Christian) proclaimed that, associates creates an avenue for building relationship with neighbours, friends and other people in the community, which significantly increases the families’ external influence and reach. Despite the commonality shared, several Christian males emphasized idea sharing and rich cultural education, as key attributes associates bring to the dinner table. They also argued that, associates provide a rich forum for discussion and idea sharing after meal. However, associates can also be a drain on families’ resources, as unplanned visitors sometimes can limit the amount of food accessed by children, which makes them very unhappy after dinner.

“In the area of having friends, colleagues or relatives visiting, and having meal together, that teaches the children that they have to share. In some settings when a visitor comes unannounced and you meet them eating, they will give you a newspaper to read. I consider that as rather unfortunate and that you are teaching the children not to share and no man is an island. … The kids will grow-up with that culture. ... Our culture pays great credence to sharing as it serves as the bond that ties people together-between you and your neighbour, between you and your classmates, between you and your relations. My children know that it is good to share and I am a firm believer in that. … Imagine you are hungry and you see your friend eating, and all he could do is to give you a newspaper to read. … However, having other nonfamily members partake in your meal occasionally, teaches the kids the culture of sharing and that is one way of expressing love and concern for one another”. (Interviewee 28, Male, Christian)

The impact of decision-making on families’ meal social interaction behaviour

Planning, as emphasized by several participants (Muslim and Christian females), is a critical decision-making factor, as it helps determine the food expenditure pattern of the family. It provides guidance as to how the family uses their resources, which is essential to their day-to-day survival and/or sustainability. They further argued that, authority in decision-making is fundamental to the success of the family, as it gives parents the ability to correct/stream-line their children’s behaviours. This, they argued, help unify the family around a common purpose and reduce chaos at mealtimes. However, many Muslim female participants, unlike their Christian counterparts, emphasized that, decision-making enhances their families’ stability, development and progress, as it is an instrument for fostering peaceful co-existence and respect in the family.

“Decision is very important in all the things we do as family from children’s school fees discussed at the dinner table to the amount spent on feeding all needs to be decided by me and my husband and sometimes we even involve the children into it. Also, decision making can be a very good control instrument. For example, if my daughter misbehaves at the dinner table and we ignore it and fail to decide on the line of action to take to correct her behaviour, she will end up becoming a bad person… It is very important because like I said it is what keeps the family together. A family without a decision-maker can never be able to enjoy stability or to maintain order at the dinner table”. (Interviewee 31, Female, Muslim)

Consistent with the views of the females, Muslim and Christian males also highlighted planning, authority and unity as essential decision-making ingredients that promotes their families’ stability and progress, which help stream-line their children’s behaviour at mealtimes.

“Decision-making in a family is very important. It is only through decision-making that we are able to plan for the future of the family. Sometimes we use decision to give the family direction and it is through decision-making that we are able to correct the wrongs of a child and make them right. If as a father I cannot make the right decision that will guide my family, they will all end up becoming very bad people in society”. (Interviewee 36, Male, Muslim)

The impact of extended family on families’ meal social interaction behaviour

Participants (Muslim and Christian females) described background difference, as key extended family issue that affect their meal social interaction behaviour. This difference makes it very difficult for appropriate cultural fit to occur between the family and their extended relations at mealtimes. The financial and economic burden that extended family brings to bear on families, were considered a crucial factor, as it determines the amount of food that is available to family members at mealtimes. This implicitly suggests that, many families have limited financial resources and therefore, cannot afford the additional burden that extended families bring to their dinner tables. However, unlike their Christian counterparts, Muslim female participants reiterated performing domestic chores, as the primary benefit extended families have on their families’ meal behaviour.

“Like I said earlier, it is source of stealing in the home, particularly if the extended family members’ character is different from those of your family. There will always be quarrels, backbiting and comparison between your children and the children of the extended family members, which breeds hatred and animosity… affects the way your family lives and they are also constraint to resources… also affect the level of expenditure in terms of the quantity of food to purchase for the family as well as the quality”. (Interviewee 27, Female, Christian)

“Well, sometimes extended family can be good, but some other times, they can be bad. Let me talk about the good first. If you have extended family members with good behaviour that can be reflected on your children and they also help with household chores. But if the extended family is one of bad character, they have the tendency of negatively influencing your children. Also, extended families can be a burden on resources, especially when things are not right at home”. (Interviewee 21, Female, Muslim)

Invariably, the Muslim and Christian males professed that background differences significantly hinders cohesion with extended families, and this also hampers relationship at the dinner table. Participants were increasingly concerned about the debilitate effect the background differences is causing in their families, including thieving, backbiting (divulging families’ internal secrets to outsiders), malice and quarrels, bad character/ behaviour and disobeying orders. Despite the shared similarity, it is indicative as suggested by several Muslim male participants that economic or financial constraints and assistance with domestic chores are major influences extended families have on their families’ mealtime behaviours.

“It poses huge problems because since they are relations, it is very difficult to drive them from home irrespective of their behaviour or character. You will always be scared of what other members of your extended family will say or feel about you. For example, if the person that joined your family from one of your extended relation, say nephew/niece, is a thief, that will induce your own son/daughter to start imitating the same behaviour. That will greatly affect interaction in the family both at the dinner table and outside it”. (Interviewee 6, Male, Christian)

“Extended family is a burden when you look at it from a financial point of view. There are also behavioural challenges associated with extended family. For example, the negative outside influence of the extended family normally feeds into the family, which may disrupt the smooth functioning of the family…The good aspects of extended family members is that if you have the right kind of person, that person will support and assist the family by helping in household chores. As a result, it eases some of the domestic chore burdens in the home”. (Interviewee 8, Male, Muslim)

The impact of identity on families’ meal social interaction behaviour

The positioning or ranking of an individual within the family is a core identity issue highlighted by all participants irrespective of their gender or religious background, as influencing their families’ meal social int