Research Paper - Anesthesiology and Clinical Science Research (2022) Volume 6, Issue 4

Airway assessment in patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures under general anesthesia: An institutional study

John Benett*Department of Anaesthesia, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- John Benett

Department of Anaesthesia

Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, USA

E-mail: johnbenett@gmail.com

Received: 28-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. AAACSR-22-68571; Editor assigned: 30-Jun-2022, PreQC No AAACSR-22-68571 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Jul-2022, QC No AAACSR-22-68571; Revised: 16-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. AAACSR-22-68571 (R); Published: 23-Jul-2022, DOI:10.35841/aaacsr-6.4.116

Citation: Benett J. Airway assessment in patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures under general anesthesia: An institutional study. Anaesthesiol Clin Sci Res. 2022;6(4):116

Abstract

Background: Preoperative management of the patient is the liability of a medical attendance. An understanding of risk factors before general anaesthesia [GA] is an important factor for preoperative management. The present study was aimed at assessing the airway of patients undergoing oral surgical procedures under general anaesthesia in our institution. Material and Methods: The study was performed under a university setting where all the data of patients who underwent oral and maxillofacial surgical procedure under general anaesthesia. The collected data was compiled, reviewed, tabulated and entered in SPSS software and statistically analysed. Results: 55% of the patients were males and the rest (45%) were females. Airway assessment in patients according to mallampati classification revealed that 57% were of class I, 38% were of class II, 3% were of class III and less than 1% was class IV. Patients who underwent FMR (40%) and cleft lip/palate (14%) had class I airway. Patients who underwent ORIF and enucleation both had class I (19.5%), class II (3.5%) airways and class I (4%), class II (1%) airways respectively. Patients who underwent orthognathic surgery had class I (11%) and class II (3.5%) airways. Patients undergoing TMJ surgery including ankylosis release, surgery for Oral submucous fibrosis had predominantly class III (1%) and class IV (2.5%) airways. Difficult airways (class III, Class IV) were present in patients undergoing procedures like TMJ ankylosis release, and surgery for oral submucous fibrosis. The association between the mallampati classification and the treatment [oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures] done under GA was statistically significant with p=0.025 (p<0.05) (chi square test). Conclusion: Assessing airway is crucial before any surgical treatment. The modified Mallampati test is easy to perform, more accurate and is commonly used to assess the airway of patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial procedures under general anesthesia. Complications might not occur if the pre-operative assessment of the airway of the patient is done properly using this classification and the surgery is planned accordingly

Keywords

Modified Mallampati Test, General Anaesthesia, Maxillofacial surgery, Airway assessment, Innovative technology.

Introduction

The failure to maintain a patient’s airway following the induction of general anaesthesia [GA] is a major concern not only for anaesthesiologists but also for the operating surgeon. An oral & maxillofacial surgeon often has to operate on difficult airway cases in the head & neck region under general anaesthesia. For securing the airway tracheal intubation, direct laryngoscopy still remains the method of choice in most cases [1]. However direct laryngoscopic intubation is difficult in 1.2% of cases and impossible in very few of cases. An unanticipated difficult laryngoscopic intubation places patients at risk of complications ranging from sore throat to even mortality. Maintaining a patient’s airway is essential for adequate oxygenation & ventilation and failure to do so even for a brief period of time can be life threatening. Approximately 600 patients die each year from the complications related to airway management. Unexpected death is probably the result of lack of accurate predictive test for difficult intubation and inadequate preoperative examination.

Difficulty in intubation is usually due to the difficulty in exposing the glottis by direct laryngoscopy. This involves a series of manoeuvres such as extending the head, opening the mouth; displacing and compressing the tongue into the submandibular space and lifting the mandible forward. The ease or difficulty in performing these manoeuvres can be assessed by many parameters. An accurate prediction of difficulty in intubation might reduce the frequency of additional maneuvers. Patients with difficult intubation can be identified by careful examination of anatomical landmarks and clinical factors [2].

Till date, the Mallampati grading remains a valuable and efficient technique for the assessment of difficult airway establishment. For elicitation of the clinical signs, the patient remains seated with his or her head in the neutral position, opens the mouth as widely as possible, and protrudes the tongue to the maximum extent [3-5]. The Mallampati classification has three classes which are based on the extent to which the base of tongue is able to mask the visibility of pharyngeal structures, including the soft palate, uvula, and faucial pillars. Samsoon and Young modified the Mallampati classification to include a fourth class, representing the extreme form of Mallampati’s class III, in which the soft palate is totally masked by the tongue in which only the hard palate is visible. In clinical practice, situations may arise where it may not be feasible for the patient to sit up for airway assessment in cases such as cervical spine injuries or disk prolapse. There is a paucity of literature regarding the applicability of the Mallampati classification in who are bedridden for any cause.

Our team has extensive knowledge and research experience that has translated into high quality publications. The present study was aimed at assessing the airway of patients undergoing oral surgical procedures under general anaesthesia in our institution [6,7].

Materials and Methods

The current study was a descriptive and retrospective study which included the data of the patients reported to the dental institution requiring oral surgical treatment under general anaesthesia. The study was set in a University which predominantly consists of the South Indian Population. The pros of the study were that it included a varied population and had the ability to perform preference analysis. The cons were that it had a very limited geographic area of coverage. The ethical approval of the current study was obtained from the institutional ethical board. The selection of patients was from the list of patients requiring oral surgical treatment under GA from the month December 2020 to February 2021. The data was obtained for the Dental Information Archiving Software which is a database of all treatments done to children who visited the oral surgery and pediatric department of the dental hospital with dental needs. The total sample size obtained from the data was 215. The inclusion criteria were all patients requiring oral surgical treatment under GA [8-12]. Exclusion criteria were all incomplete and censored data. The data was cross verified using photographs and reviewed by an additional reviewer to minimize error. The data has high internal validity and low external validity. The data was entered in a methodical manner and was tabulated in Microsoft excel sheet. The tabulated data was imported to SPSS software (IBM) for statistical analysis.

Results

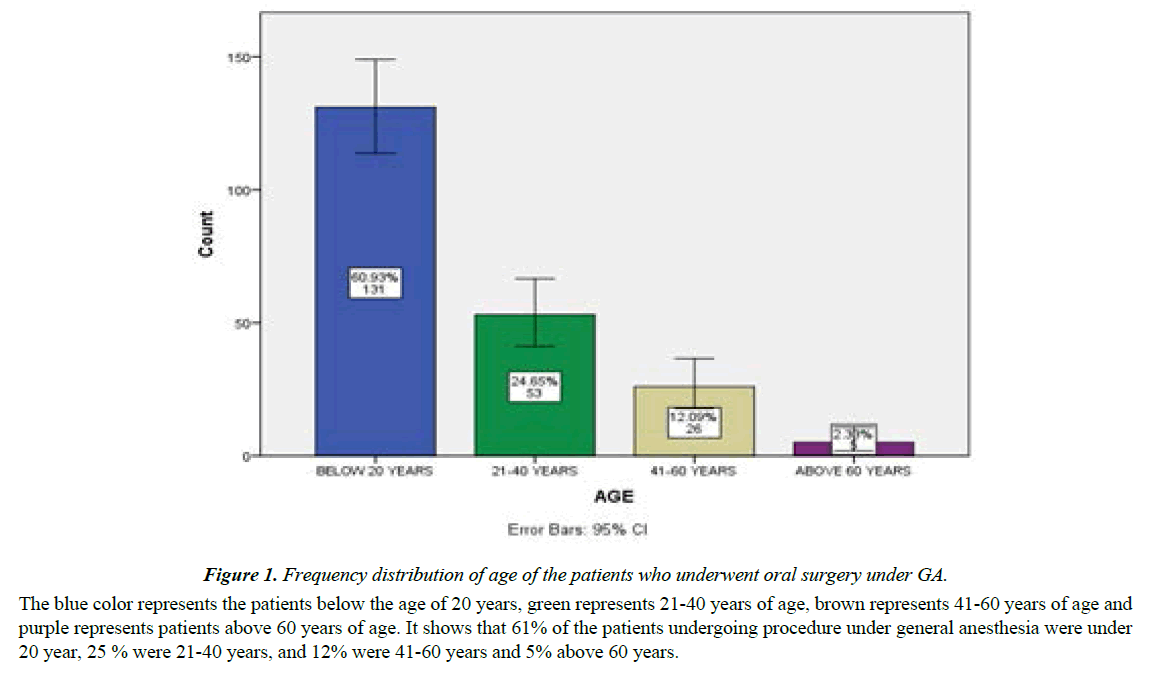

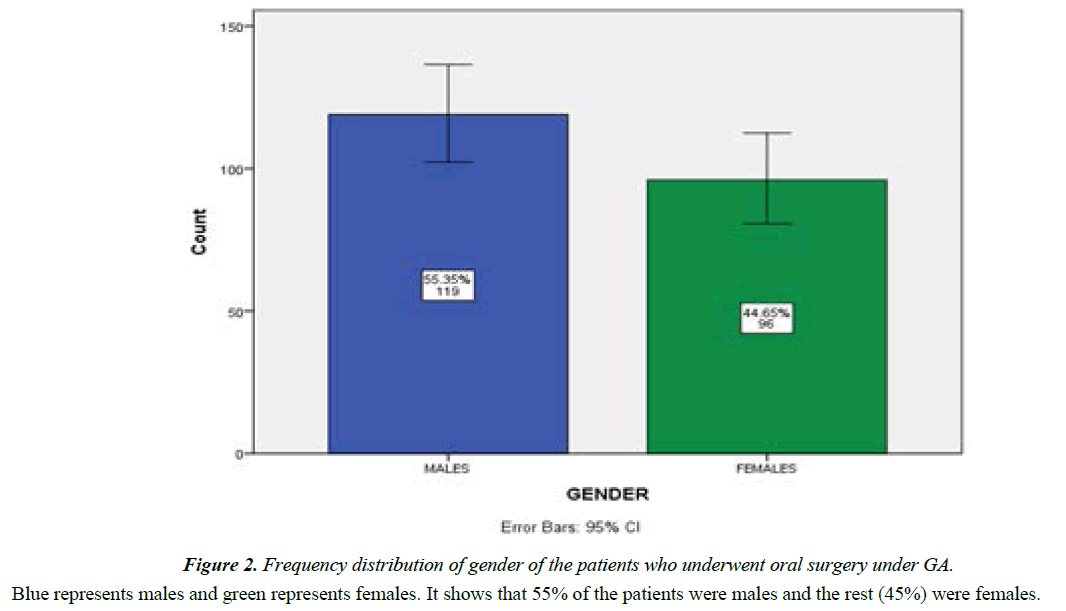

Frequency distribution of age of patients is shown in Figure 1. It shows that 61% of the patients undergoing procedure under general anesthesia were under 20 year, 25 % were 21-40 years, and 12% were 41-60 years and 5% above 60 years. Frequency distribution of gender is shown in Figure 2. It shows that 55% of the patients were males and the rest (45%) were females.

Figure 1: Frequency distribution of age of the patients who underwent oral surgery under GA.

The blue color represents the patients below the age of 20 years, green represents 21-40 years of age, brown represents 41-60 years of age and purple represents patients above 60 years of age. It shows that 61% of the patients undergoing procedure under general anesthesia were under 20 year, 25 % were 21-40 years, and 12% were 41-60 years and 5% above 60 years.

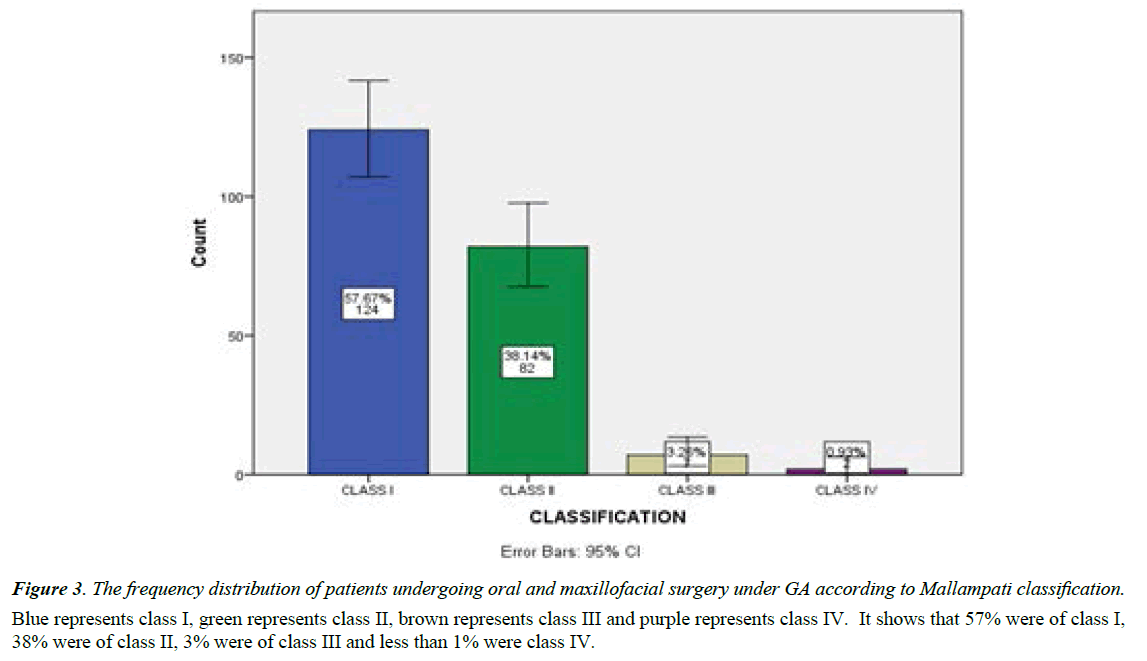

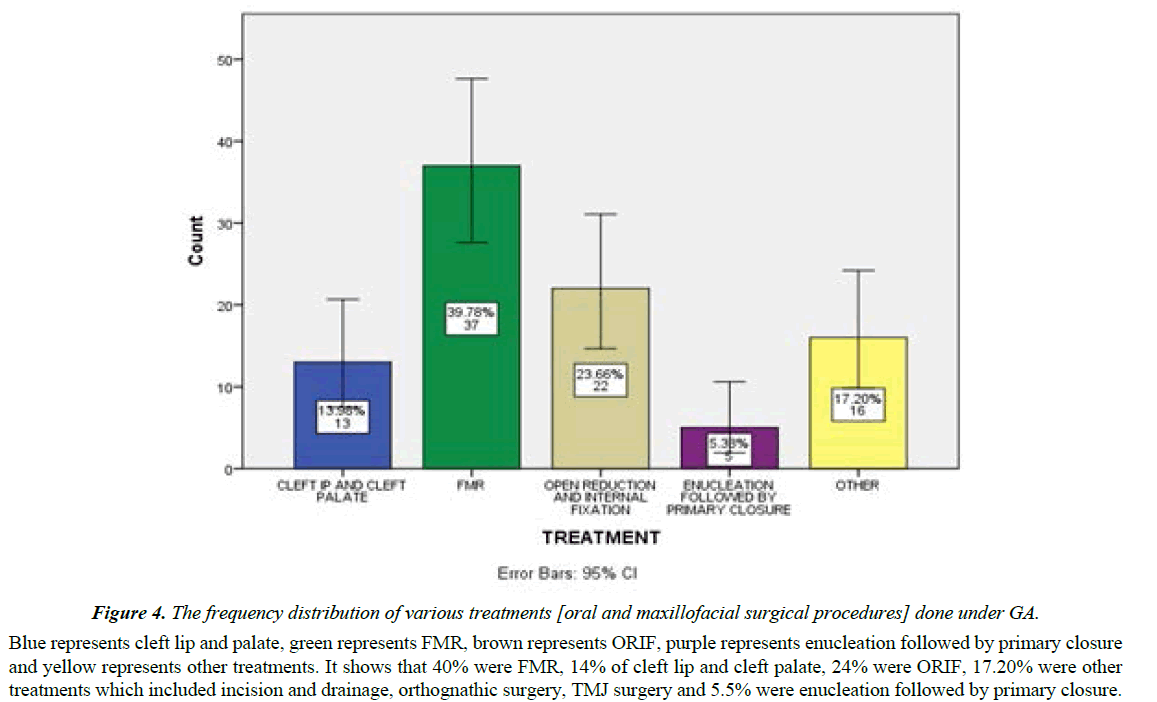

Frequency distribution of patients according to Mallampati classification is shown in Figure 3. It shows that 57% were of class I, 38% were of class II, 3% were of class III and less than 1% was class IV. The treatment done under GA is shown in Figure 4. 40% were FMR, 14% of cleft lip and cleft palate, 24% were open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), 15.5% were other treatments which included incision and drainage, orthognathic surgery, TMJ surgery including ankylosis release and surgery of oral submucous fibrosis and 5.5% were enucleation followed by primary closure.

Figure 3: The frequency distribution of patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial surgery under GA according to Mallampati classification.

Blue represents class I, green represents class II, brown represents class III and purple represents class IV. It shows that 57% were of class I, 38% were of class II, 3% were of class III and less than 1% were class IV.

Figure 4: The frequency distribution of various treatments [oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures] done under GA.

Blue represents cleft lip and palate, green represents FMR, brown represents ORIF, purple represents enucleation followed by primary closure and yellow represents other treatments. It shows that 40% were FMR, 14% of cleft lip and cleft palate, 24% were ORIF, 17.20% were other treatments which included incision and drainage, orthognathic surgery, TMJ surgery and 5.5% were enucleation followed by primary closure.

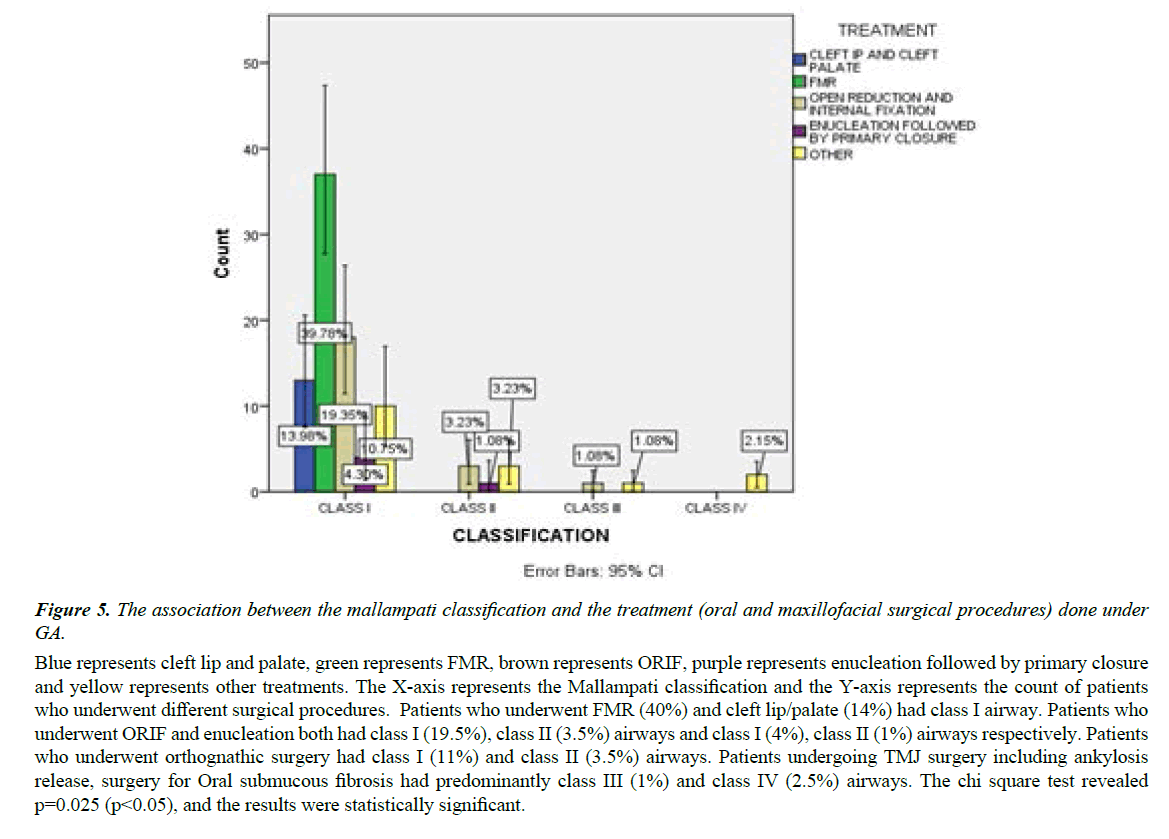

The association between the mallampati classification and the treatment [oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures] done under GA was evaluated. The chi square test revealed p=0.025 (p<0.05), and the results were statistically significant. Patients who underwent FMR (40%) and cleft lip/palate (14%) had class I airway. Patients who underwent ORIF and enucleation both had class I (19.5%), class II (3.5%) airways and class I (4%), class II (1%) airways respectively. Patients who underwent orthognathic surgery had class I (11%) and class II (3.5%) airways. Patients undergoing TMJ surgery including ankylosis release, surgery for Oral submucous fibrosis had predominantly class III (1%) and class IV (2.5%) airways (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The association between the mallampati classification and the treatment (oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures) done under GA.

Blue represents cleft lip and palate, green represents FMR, brown represents ORIF, purple represents enucleation followed by primary closure and yellow represents other treatments. The X-axis represents the Mallampati classification and the Y-axis represents the count of patients who underwent different surgical procedures. Patients who underwent FMR (40%) and cleft lip/palate (14%) had class I airway. Patients who underwent ORIF and enucleation both had class I (19.5%), class II (3.5%) airways and class I (4%), class II (1%) airways respectively. Patients who underwent orthognathic surgery had class I (11%) and class II (3.5%) airways. Patients undergoing TMJ surgery including ankylosis release, surgery for Oral submucous fibrosis had predominantly class III (1%) and class IV (2.5%) airways. The chi square test revealed p=0.025 (p<0.05), and the results were statistically significant.

Discussion

The current study shows that most of the oral surgery which was under general anaesthesia was done for patients under the age of 20. Limited literature is available regarding the indications for treatment of patients of different age groups under general anesthesia. Dougherty attempted to review the literature in this area almost a decade ago and encountered a lack of relevant evidence. Nonetheless, several reviews have identified that the primary indication for general anesthesia is the young age group or the lack of patient cooperation due to anxiety, intellectual disability, or some other impairment [12].

Most of the patients who were included in the current study were males. This is in correlation to similar studies done around the world. Men experience more dental trauma than women by approximately a 2:1 ratio [13]. This is attributed to the fact that more men participate in contact sports and risky behaviors, and are at a greater risk for both intentional and unintentional physical injuries. The chance of incurring trauma and damage to head and neck is exacerbated by men being less likely to wear mouthguards or other protective gears. Experts believe mouthguards can also cushion head trauma. It must be noted that oral surgeries can also be done for aesthetic purposes. There is no evidence to prove that males are more concerned about aesthetics than women [14-18].

In addition to dental assessments, examination of the oral cavity may facilitate anesthetic assessment of the patient's airway. Airway management is one of the most crucial aspects of patient care during sedation. Pre-operative assessment of airway is often standardized using the Mallampati classification, which involves the visual inspection of the distance from the base of the tongue to the roof of the mouth while the patient is in a seated position with their mouth open and tongue protruded. Mallampati classification includes class I to IV; higher the class, lesser is the airway clearance, difficulty in intubation, and an increase in likelihood of obstruction. This study describes the airways prevailing in the patients undergoing various oral and maxillofacial procedures under GA. Difficult airways (class III, Class IV) were present in patients undergoing procedures like TMJ ankylosis release, and surgery for oral submucous fibrosis [18,19].

Conclusion

Assessing airway is crucial before any surgical treatment. The modified Mallampati test is easy to perform, more accurate and is commonly used to assess the airway of patients undergoing oral and maxillofacial procedures under general anesthesia. Complications might not occur if the pre-operative assessment of the airway of the patient is done properly using this classification and the surgery is planned accordingly.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflict of interest.

References

- Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Caplan RA, et al. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):251-70.

- Phero JC, Rosenberg MB, Giovannitti JA. Adult airway evaluation in oral surgery. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Clinics. 2013;25(3):385-99.

- Williamson JA, Webb RK, Szekely S, et al. Difficult intubation: an analysis of 2000 incident reports. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 1993;21(5):602-7.

- Paix AD, Williamson JA, Runciman WB. Crisis management during anaesthesia: difficult intubation. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2005;14(3):e5-.

- Langeron O, Masso E, Huraux C, et al. Prediction of difficult mask ventilation. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2000;92(5):1229-36.

- Çelik G, Zengin S, Ergün MO, et al. Correlation between neck circumference measurement and obesity type with difficult intubation in obese patients undergoing elective surgery. Journal of Surgery and Medicine. 2021;5(9):912-6.

- Law JA. From the Journal archives: Mallampati in two millennia: its impact then and implications now. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d'anesthésie. 2014;61(5):480-4.

- Samsoon GL, Young JR. Difficult tracheal intubation: a retrospective study. Anaesthesia. 1987;42(5):487-90.

- Hagberg C, Georgi R, Krier C. Complications of managing the airway. Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology. 2005;19(4):641-59.

- Sartain J. Book Review: Complications in Anesthesia.

- Abrahams H, Bygrave C, Doyle C, et al. Does neck circumference predict difficult laryngoscopy in morbidly obese patients?: 19AP2–5. European Journal of Anaesthesiology| EJA. 2010;27(47):248-9.

- Rosenblatt WH. The Airway Approach Algorithm: a decision tree for organizing preoperative airway information. Journal of clinical anesthesia. 2004;16(4):312-6.

- Martinez-Hurtado ED, Sanchez-Merchante M, Corcóstegui PR, et al. An Update on Airway Management Registry and Organization. An Update on Airway Management. 2020;3:312-27.

- Jun JH, Baik HJ, Kim JH, et al. Comparison of the ease of laryngeal mask airway ProSeal insertion and the fiberoptic scoring according to the head position and the presence of a difficult airway. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology. 2011;60(4):244-9.

- Brodsky JB, Lemmens HJ, Brock-Utne JG, et al. Morbid obesity and tracheal intubation. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2002;94(3):732-6.

- Pc J, Marimuthu T, Devadoss P, Kumar SM. Prevalence and measurement of anterior loop of the mandibular canal using CBCT: A cross sectional study. Clinical implant dentistry and related research. 2018;20(4):531-4.

- Wahab PA, Madhulaxmi M, Senthilnathan P, et al. Scalpel versus diathermy in wound healing after mucosal incisions: A split-mouth study. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2018;76(6):1160-4.

- kiran Mudigonda S, Murugan S, Velavan K, et al. Non-suturing microvascular anastomosis in maxillofacial reconstruction-a comparative study. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery. 2020;48(6):599-606.

- Narayanasamy RK, Muthusekar RM, Nagalingam SP, et al. Lower pretreatment hemoglobin status and treatment breaks in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma during concurrent chemoradiation. Indian Journal of Cancer. 2021;58(1):62.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref