Research Article - Biomedical Research (2017) Volume 28, Issue 17

Added value of diffusion-weighted MR imaging to non-enhanced CT in the evaluation of acute abdominopelvic pain

Oğuzhan Özdemir*, Yavuz Metin, Filiz Taşçı, Nurgül Orhan Metin, Özlem Bilir, Özcan Yavaşi and Ali Küpeli

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Radiology, Rize, Turkey

- *Corresponding Author:

- Oğuzhan Özdemir

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University

Faculty of Medicine

Department of Radiology

Rize, Turkey

Accepted on August 22, 2017

Abstract

Objective: When performing a Non-Enhanced Computed Tomography (NECT) scan, the efficacy generally reduces, and an additional CECT may become inevitable for final diagnosis. This prospective study aims to determine the added value of Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) when combined to NECT in the diagnosis of acute abdominopelvic pain (acute abdomen) and the diagnostic efficacy of combined imaging (DWI and NECT) compared with CECT.

Methods: Between June 2014 and August 2016, 293 patients (133 male, 160 female) imaged with NECT and DWI, and 394 control patients (174 male, 220 female) imaged with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) for acute abdominopelvic pain were enrolled in this prospective study. DWI was obtained with b factors 0, 500 and 1000 s/mm2 and assessed with qualitative analysis.

Results: NECT provided 70.1% sensitivity and 76.0% specificity and 71.6% accuracy. The combined protocol (NECT and DWI) revealed 96.7% sensitivity, 82.6% specificity and 92.8% accuracy. CECT provided 93.0% sensitivity and 79.4% specificity and 90.3% accuracy. The addition of DWI to NECT provided a 26.6% and 6.6% increase in the sensitivity and, specificity respectively. There was 21.2% significant increase of accuracy in favour of the combined imaging (p<0.001). However, there was no significant difference of accuracy between CECT and combined imaging (p=0.204).

Conclusion: DWI is an efficient technique for the diagnosis of acute abdominopelvic pain. We recommend using DWI when NECT is inevitable for different reasons. It may increase the diagnostic accuracy of NECT to avoid an additional CECT scan.

Keywords

Acute abdominopelvic pain, Emergency department, Computed tomography, Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI).

Introduction

Acute abdominopelvic pain (acute abdomen) is a common presentation in patients who are admitted to emergency department. Differential diagnosis of acute abdomen ranges from mild to life-threatening conditions. The most common causes are acute appendicitis, diverticulitis, cholecystitis and bowel obstruction and less common causes include perforated viscous and bowel ischemia. Diagnostic imaging is generally performed following detailed patient history, physical examination and laboratory tests [1]. An accurate and quick diagnosis is essential for the appropriate management in emergency settings. Imaging sometimes can change our preliminary diagnosis and decision making about management or it can increase the level of diagnostic certainty [2,3].

Abdominal plain radiography, Ultrasonography (US) and Computed Tomography (CT) are the traditional imaging modalities most commonly used for acute abdomen in the emergency settings. Conventional radiography has limited value in acute abdomen [1,2]. Ultrasonography also has many limitations, such as operator dependency, obesity, abdominal gas and ineffective ability to solve complicated disease processes [4,5]. On the other hand, CT has high sensitivity and specificity over 90% in acute abdomen especially when performed with contrast administration. CT is reported to provide more consistent results than US in evaluation of acute abdomen. It is known that intravenous administration of contrast agent facilitates the evaluation and needed for diagnostic confidence [6]. However, some conditions such as; decreased renal function, presence of some chronic disease states, advanced patient age and previous allergic reactions to contrast agents, limits the use of intravenous contrast agents. Additionally, many clinicians, as in case of our emergency department practice, avoid Contrast Enhanced CT (CECT) because of fears of contrast media-associated nephrotoxicity or allergic reactions. Although Non-Enhanced CT (NECT) can be applied for acute abdomen in obligatory conditions such as impaired renal function, it would not be as effective as CECT. In some of these cases, repeated examinations with contrast administration might be required which result in increased radiation dose and delay in diagnosis.

There are many studies in the literature reporting the use of rapid MR imaging techniques that are particularly applicable for emergency settings [6-12]. Diffusion-Weighted MRI (DWI) is an active field of research for this purpose. It gives information related to cellularity of tissues. A considerable number of articles on the contribution of DWI to evaluate the inflammatory and neoplastic diseases of the abdomen have been published [13,14]. Recent studies have also proved the effectiveness of DWI in acute abdominal situations [11-13].

In the present study, our primary reason for adding DWI was the result of the high number NECT scans performed in emergency settings by the decision of emergency department physicians. As most patients with acute abdomen would need a CECT scan as a gold standard imaging method, in case of a NECT scan, demand for an additional contrast-enhanced scan (mostly CECT) generally seems inevitable. As far as we know, there are no published studies including contribution of DWI to NECT in diagnosis of acute abdomen at emergency settings. Considering the fact that DWI as a fast and non-invasive technique, is efficient in the diagnosis of acute abdominal pathologies, we added it to the NECT protocol for suitable (no known contraindications for MR) patients. By this way, we aimed to increase the diagnostic efficacy of NECT and investigated whether it may avoid CECT repeating, additional MR sequences or other imaging modalities in some patients. With this prospectively designed study, we also aimed to show whether DWI can play a role in imaging of acute abdominal conditions, as in acute cerebrovascular diseases in the emergency department.

Methods and Materials

Study population

This is a prospective study carried out from June 2014 to August 2016 among patients having acute abdominopelvic pain, who were admitted to emergency department. It was planned at the beginning (from June 2014) to perform DWI after NECT in patients with acute abdominopelvic pain. A total of 293 consecutive patients (133 male, 160 female) scanned with NECT followed by DWI (within a few hours) constituted the study group. In the same period, 394 consecutive patients (174 male, 220 female) scanned primarily with the gold standard imaging method for acute abdomen, that is CECT, formed the control group. The control group consisted of different patients but with similar pathologies to the study group. All patients in both groups underwent abdominal plain radiography and US as the initial imaging method. A CT scan was performed with requirement of a further diagnostic imaging method on the basis of clinical and laboratory findings. When the diagnosis could not be achieved with NECT, even by adding DWI and knowing its potential benefits, it did not prevent our decision to perform additional standard imaging (e.g. CECT, contrast-enhanced MRI or any other modality) for the final diagnosis. Pregnant women, children under the age of 16, clinically unstable patients, patients with poor cooperation and those with claustrophobia were excluded from the study. Since patients with urinary stone disease are routinely imaged with NECT, we excluded most patients with urinary stone disease except those with findings of pathologies complicating urinary stone disease such as pyelonephritis, pyonephrosis or renal abscess. We also did not add patients with gastrointestinal perforation, since most of those had typical clinical presentation and plain radiography findings, and they were scanned primarily with CECT by the decision of emergency department physician. In this non-randomized prospective study, we tried to construct the study and control group of similar diagnoses in order to constitute a base for objective comparison. Final diagnoses in study group were obtained with histopathologic analysis after surgical operation, urine culture, laboratory findings, colonoscopy, percutaneous sampling, CECT, Doppler US, additional MR sequences (with contrast-enhanced images) and CT or MR angiography. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and written consent was obtained from each patient before imaging.

Imaging protocols

Diffusion-weighted MR imaging was performed by a 1.5-T MR imaging unit (Magnetom Aera; Siemens) in supine position with eight channel phased-array coil. Axial diffusion-weighted single-shot echoplanar sequence (EPI) with fat suppression without breath holding was performed. A three-plane gradient echo was used as localizer sequence at the beginning of the examination. The imaging parameters were repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE): 7500/80 ms; Section thickness: 5 mm; Intersection gap: 30%; Matrix size: 192 × 192; Number of excitations (NEX): 2; Parallel imaging with reduction factor: 2; Field of view (FOV): 400 × 400 mm; acquisition time: approximately 4 min and water excitations with b values of 0, 500, and 1000 s/mm2. No any MR sequence was obtained for study group except DWI.

Computed tomography scan was performed with a 16-slice multi-detector-row scanner (Toshiba Alexion™/ Advance; Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation Nashu). The CT protocol was as follows: 120 kVp, tube current of 150-165 mAs, maximum 2.5 mm collimation, slice thickness of 3 mm, and 0.5 s rotation time. Intravenous contrast agent was not given to the study group. Imaging for control group was performed at portal venous phase (scanning delay, 60-70 s) after a total of 100 ml non-ionic contrast agent (Ultravist; Bayer) injection by a power injector at a rate of 4 ml/s. None of the patients in study and control groups took enteral contrast agent. Decision on patients imaging management at presentation (use of NECT or CECT) was made by the emergency department physicians.

Image analysis

All CT and DWI images were evaluated in a dedicated workstation (Syngo. via; Siemens). Two abdominal radiologists reviewed NECT and DWI images in study group, while two different radiologists reviewed CECT images in control group. The radiologists had at least five years’ experience in body CT, MRI and emergency radiology. Possible diagnoses were obtained by consensus of radiologists in each group. The readers were aware of the clinical and laboratory findings as well as initial imaging methods (e.g. plain radiography and US).

In the study group, the radiologists initially reviewed NECT images. Before DWI, it was decided by the radiologists whether NECT images were diagnostic or any additional imaging modality such as Doppler US, CECT or contrast-enhanced MR would be performed. Regardless of the choices whether decision was another modality (mostly CECT) or NECT images were enough for diagnosis, all patients in the study group were send to MR room for DWI. On NECT images, suspicious features that might point out to a focus of acute abdominopelvic pain were recorded. Intestinal wall thickening, findings of ileus, mesenteric stranding, peritoneal thickening, gallbladder wall thickening, pancreatic enlargement with peripancreatic fatty tissue stranding, fluid collections, perirenal fatty tissue stranding, presence of an inflammatory mass, increase of ovarian diameter and presence of ovarian mass were the features searched on NECT as potential causes of acute pain. Afterwards, DWIs were evaluated taking account the suspicious features on NECT. Suspicious focus defined with NECT was searched on DWIs. If the focus had high signal intensity on b-1,000 s/mm2 images and a low intensity on ADC maps it was considered as positive. On the other hand, iso-or hypointense signal on DWI with hyperintensity on ADC map was considered as negative. Imaging findings of all modalities were also classified as being simple (noncomplicated) or complicated (e.g. simple appendicitis versus perforated appendicitis). b-0 and 500 s/mm2 images were used to evaluate anatomical details. ADC values were only used to specify and/or confirm the pathology that showed various degree of diffusion restriction, otherwise they would not be used for statistical analysis. Finally, NECT images were re-evaluated and a diagnosis was made in consensus by radiologists. Extra findings on DWI were also noted and checked during the second evaluation of NECT images.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analyzed applying the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 13.0 Statistical Software; SPSS Inc.). The medians and ranges for patient ages were given. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to show deviation from normal distribution. The parametric Student's t test was used to compare the age of study and control groups. Chi-square test was used to compare the gender of study and control groups. Sensitivity, specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), Negative Predictive Value (NPV), Positive Likelihood Ratio (PLR), Negative Likelihood Ratio (NLR) with their 95% CI, and accuracy of NECT and combined imaging (NECT and DWI) were calculated. The McNemar test was used to compare the diagnostic performances of NECT and combined protocol. Also, the Chi-square test was used to compare the accuracy of CECT and combined method. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results

In the present study, 293 patients were evaluated with NECT and DWI for acute abdomen. The reasons for NECT scanning were as follows: 15 (5.1%) patients had renal failure, 27 (9.2%) had previous allergic reactions to contrast agents, 67 (22.8%) patients did not give consent to the use of contrast agent and the remaining 184 patients (62.7%) were imaged with NECT by the decision of emergency department physicians without any contraindication to contrast agent. The control group consisted of 394 patients who were evaluated with CECT.

The median ages of study group (133 male, 160 female) and control group (174 male, 220 female) were 47 years (range 19-82) and 46 y (range 19-87), respectively. There were not significant differences between the age and sex distribution of the groups (p=0.279 for age, p=0.582 for gender).

Of the 293 study and 394 control group patients, 75 (48.9%), 76 (19.2%) were found to be normal and 218 (51%), 318 (80.7%) had a certain final diagnosis related to a cause of acute abdominopelvic pain, respectively. The results and demographic features of both groups are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Also the results of diagnostic performance of imaging modalities of most common diagnoses regarding complicated (or severe form) disease prediction of both groups are shown in Table 3.

| Study group | Control group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NECTa | NECT and DWIb | CECTc | |||

| Diagnosis | Number (%) | Correct Diagnosis Number (%) | Correct Diagnosis Number (%) | Number (%) | Correct Diagnosis Number (%) |

| Acute appendicitis | 51 (17.4%) | 46 (90.2%) | 51 (100%) | 88 (22.3%) | 86 (97.8%) |

| Pyelonephritis | 28 (%9.6) | 16 (61.6%) | 26 (92.9%) | 40 (10.2%) | 34 (85%) |

| Acute diverticulitis | 24 (8.2%) | 20 (83.4%) | 24 (100%) | 28 (7.1%) | 28 (100%) |

| Acute cholecystitis | 21 (7.2%) | 16 (76.2%) | 21 (100%) | 22 (5.6%) | 20 (91%) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 20 (6.8%) | 16 (84.3%) | 19 (95%) | 26 (6.6%) | 24 (92.4%) |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 12 (4.1%) | 9 (81.9%) | 11 (91.7%) | 20 (5.1%) | 20 (100%) |

| Bowel obstruction | 11 (3.8%) | 8 (72.8%) | 11 (100%) | 14 (3.6%) | 12 (85.8%) |

| Infammatory bowel disease | 10 (3.4%) | 7 (77.8%) | 9 (90%) | 16 (4.1%) | 14 (87.5%) |

| Intestinal ischemia | 9 (3.1%) | 1 (12.5%) | 8 (88.9%) | 8 (2%) | 8 (100%) |

| Complicated ovarian cyst | 7 (2.4%) | 3 (42.9%) | 7 (100%) | 20 (5.1%) | 16 (80%) |

| Renal infarction | 7 (2.4%) | 2 (28.6%) | 7 (100%) | 8 (%2) | 8 (100%) |

| Myoma torsion | 6 (2%) | 3 (60%) | 5 (83.4%) | 6 (%1.5) | 6 (100%) |

| Ovarian torsion | 6 (2%) | 3 (50%) | 6 (100%) | 12 (%3) | 8 (66.7%) |

| Mesenteric panniculitis | 5 (1.7%) | 3 (60%) | 5 (100%) | 10 (%2.5) | 10 (100%) |

| Pubic bone metastasis | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Normal | 75 (25.6%) | - | - | 76 (19.3%) | - |

| Total | 293 (100%) | 394 (100%) | |||

| aNon-enhanced computed tomography; bDiffusion weighted imaging; cContrast-enhanced computed tomography. | |||||

Table 1. Results of study and control groups.

| Study Group (n=293) | No | % |

|---|---|---|

| Male-Female | 132-160 | 45.2-54.8 |

| Correct Diagnosis for NECTa | 211 | 72.0 |

| Correct Diagnosis for NECT and DWIb | 273 | 93.4 |

| (Mean ± SD) | Range | |

| Age | 48 ± 15.5 | 19-82 |

| Control Group (n=394) | No | % |

| Male-Female | 174-222 | 43.9-56.1 |

| Correct Diagnosis for CECTc | 357 | 90.1 |

| (Mean ± SD) | Range | |

| Age | 46 ± 15.2 | 19-87 |

| aNon-enhanced computed tomography; bDiffusion weighted imaging; cContrast-enhanced computed. | ||

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of patients and correct diagnosis number of imaging modalities.

| Diagnosis | Feature | Study group | Control group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NECTa | NECT and DWIb | Total | CECTc | Total | ||

| Acute appendicitis | Complicated | 11 (64.7%) | 14 (82.3%) | 17 | 24 (92.3%) | 26 |

| Acute diverticulitis | Complicated | 3 (42.8%) | 7 (100%) | 7 | 11 (100%) | 11 |

| Acute pyelonephritis | Complicated | 2 (33.3%) | 6 (100%) | 6 | 10 (90.9%) | 11 |

| Acute cholecystitis | Complicated or severe form | 5 (50%) | 10 (100%) | 10 | 6 (66.6%) | 9 |

| Acute pancreatitis | Complicated or severe form | 2 (40%) | 5 (100%) | 5 | 9 (100%) | 9 |

| aNon-enhanced computed tomography; bDiffusion weighted imaging; cContrast-enhanced computed tomography. | ||||||

Table 3. Accurate detection number and rate of complicated disease or severe form of some common diagnoses.

Of the 218 patients 153 were correctly diagnosed with NECT. NECT provided 70.1% sensitivity, 76.0% specificity and 71.6% accuracy. The combined protocol (NECT and DWI) revealed 96.7% sensitivity, 82.6% specificity and 92.8% accuracy. In the control group, CECT provided 93.0% sensitivity, 79.4% specificity and 90.3% accuracy. The diagnostic performances of NECT, CECT and the combined protocol are shown in Table 4. From the study and control groups, 102 and 150 patients underwent surgery, nine and 16 patients percutaneous abscess drainage, respectively. All other patients received medical treatment.

In the current study, addition of DWI provided a 26.6% and 6.6% increase in the sensitivity and specificity of NECT, respectively. There was 21.2% increase of accuracy in favour of the combined imaging (p<0.001). There was no significant difference between the accuracies of CECT and combined protocol including NECT and DWI (p=0.204).

| NECTa | NECT and DWIb | CECTc | |

|---|---|---|---|

| True-positive (No. of lesions) | 153 | 211 | 294 |

| True-negative (No. of lesions) | 57 | 62 | 62 |

| False-positive (No. of lesions) | 18 | 13 | 16 |

| False-negative (No. of lesions) | 65 | 7 | 22 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 70.1 | 96.7 | 93 |

| Specificity (%) | 76 | 82.6 | 79.4 |

| PPVd (%) | 89.4 | 94.1 | 94.8 |

| NPVe (%) | 46.7 | 89.8 | 73.8 |

| Accuracy (%) | 71.6 | 92.8 | 90.3 |

| aNon-enhanced computed tomography; bDiffusion weighted imaging; cContrast-enhanced computed tomography; dPositive predictive value; eNegative predictive value. | |||

Table 4. The diagnostic performances of imaging modalities.

Discussion

Computerized tomography is the most commonly used imaging modality in acute abdominopelvic pain with high sensitivity and specificity over 90%. The use of multi-detector CT scanners has increased the accuracy rates in the diagnosis of specific disease processes such as appendicitis and diverticulitis causing acute abdomen. In acute abdomen, an entire abdominal scanning with the use of intravenous administration of an iodinated contrast agent is recommended. Although abdominal CT can be performed without contrast agent, it is reported that CECT has better accuracy rates, for example a positive predictive value of 95% reported for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis [15-18]. Today, with the development of fast imaging techniques, MRI has become an important imaging method in evaluation of acute abdomen. DWI is an active field of research for this purpose.

In some clinical practices NECT is frequently used for the imaging of acute abdomen despite the absence of any contraindication to contrast use. In our clinical practice, this is mainly due to the preferences of emergency department physicians observed particularly in overnights, when no or limited number of radiologists and/or other radiology staffs are active in duty.

In this present study, NECT had limited efficacy in the diagnosis of pathologies causing acute abdomen with a low rate of sensitivity and accuracy of 70.1% and 71.6%, respectively. Combination of DWI with NECT significantly increased the diagnostic accuracy to 92.8%. (p<0.001). On the other hand, CECT showed 90.3% accuracy. There was no significant difference between the accuracies of combined protocol and CECT (p=0.204).

Initial US as a diagnostic strategy in acute abdomen before CT examination can reduce unnecessary CT scans and radiation exposure [19,20]. In our study, all patients underwent US examination before NECT or CECT. A CT scan was performed when US was either inefficient or a further diagnostic modality was needed on the basis of clinical and laboratory findings. When US findings were enough to make diagnosis, no further imaging was performed. Therefore, most cases of urinary stone disease, acute appendicitis and cholecystitis were not included to this study.

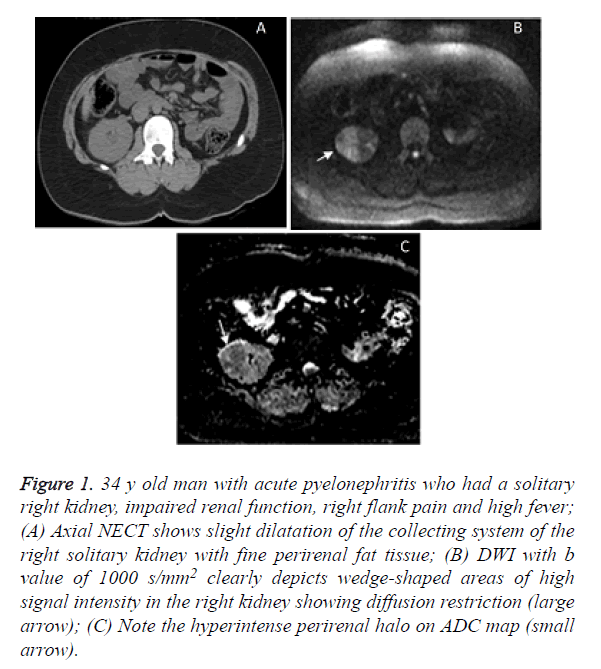

Computed tomography is currently applied following inconclusive US findings for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. The sensitivity and specificity of NECT for appendicitis is reported as 90-95%, while it approaches to 99% with intravenous contrast use [21]. Our results are compatible with the literature. In the present study, addition of DWI increased the diagnostic efficacy up to that of CECT. We have found that NECT was successful in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis with an accuracy rate of 90%. On the other hand, NECT discriminated complicated appendicitis only in 11 of 17 patients (64.7%) while in combined imaging the rate increased to 82%. This was 92% for CECT. All the diagnoses of acute appendicitis were confirmed at surgery. It seems that DWI not only has the potential to improve the diagnostic performances of NECT up to that of the CECT but also it can improve diagnostic efficacy in complicated versus uncomplicated appendicitis. We suggest that a greater number of patients should be studied in order to evaluate the role of DWI for this aspect, alone or combined to a CT scan. The diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis is usually based on clinical and laboratory data. Imaging is recommended if patients have atypical, severe symptoms and relevant comorbidities such as diabetes, organ transplant, or immunosuppression [13]. In the present study, there were 28 such patients with acute pyelonephritis, whose initial US evaluation did not show prominent degree of hydronephrosis or give enough information regarding the clinical status. Hence, CT imaging was decided. Sixteen of 28 patients (57%) with NECT and all patients with combined imaging were correctly diagnosed (Figure 1), while CECT provided 85% accuracy in the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis. The final diagnosis of uncomplicated cases was confirmed by urine analysis and culture, while in complicated ones either CECT or contrast-enhanced MRI was finally used. For complication discrimination, NECT diagnosed one pyonephrosis, one perinephritic abscess and combined imaging found all complications (3 pyonephrosis, one renal abscess and two perinephritic abscesses), while CECT diagnosed 10 (6 pyonephrosis, 4 perinephritic abscesses) of 11 complications. CECT missed one pyonephrosis that was proved at laboratory.

Figure 1. 34 y old man with acute pyelonephritis who had a solitary right kidney, impaired renal function, right flank pain and high fever; (A) Axial NECT shows slight dilatation of the collecting system of the right solitary kidney with fine perirenal fat tissue; (B) DWI with b value of 1000 s/mm2 clearly depicts wedge-shaped areas of high signal intensity in the right kidney showing diffusion restriction (large arrow); (C) Note the hyperintense perirenal halo on ADC map (small arrow).

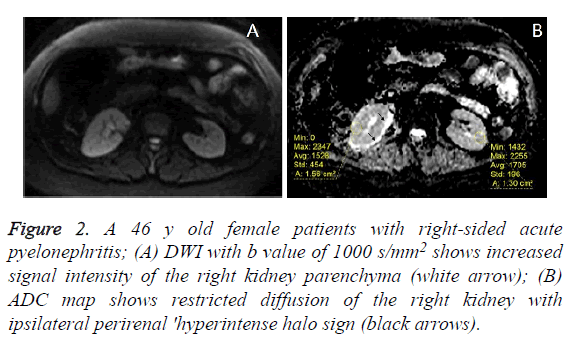

Another remarkable finding of DWI was that 25 of 26 patients (96%) had a hyperintense halo around the effected kidney on ADC maps. From the point of view of our clinical practice, we usually encounter bilaterally a thin, hyperintense perinephric halo on ADC maps of especially elderly healthy patients without a known renal disease. But the ‘hyperintense halo’ sign we faced is ipsilateral and thicker (Figure 2). To our knowledge, this sign has not been described in the literature so far. Perinephric edema might be the cause of this hyperintense halo on ADC map. However, we do not know whether or not this sign is seen in the other acute inflammatory disease processes of the kidney. This point must be investigated with further studies.

Figure 2. A 46 y old female patients with right-sided acute pyelonephritis; (A) DWI with b value of 1000 s/mm2 shows increased signal intensity of the right kidney parenchyma (white arrow); (B) ADC map shows restricted diffusion of the right kidney with ipsilateral perirenal 'hyperintense halo sign (black arrows).

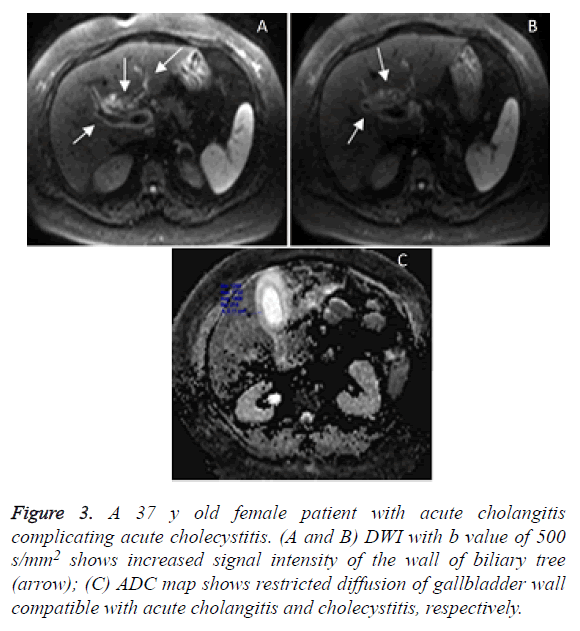

Although US is sufficient in the diagnosis of most acute cholecystitis, subtle or complicated cases might necessitate further imaging. On DWI, diffuse and symmetric high signal intensity in gallbladder wall is seen in case of acute cholecystitis [14]. In our study, NECT and CECT were obtained in acute cholecystitis patients diagnosed by US, when clinical and laboratory findings also pointed complications such as perforation, pancreatitis or cholangitis. Diagnosis of pathologies complicating cholecystitis in the study group was finally confirmed by either CECT or contrast-enhanced MRI. In the present study, those initially diagnosed as acute cholecystitis by US and later found to have also prominent imaging and laboratory findings of pancreatitis were included to pancreatitis group instead of cholecystitis group. Except for five, 16 cases with acute cholecystitis were correctly diagnosed at NECT and all 21 acute cholecystitis were correctly diagnosed by combined method in our study. Of 22 acute cholecystitis, 20 patients with acute cholecystitis were diagnosed correctly with CECT in control group. Comparing the efficacy to show severe forms and complications of cholecystitis, two emphysematous cholecystitis and 3 perforations with NECT, and two emphysematous cholecystitis, 3 perforations and 5 cholangitis were correctly diagnosed with combined method. Patients with cholangitis had increased signal in the wall of biliary tree on DWI with lower b values (0 or 500 s/mm2). CECT correctly diagnosed one emphysematous cholecystitis and 5 perforations while it was not successful in the diagnosis of cholangitis in 3 patients as in NECT. Thus, the present study showed that DWI is highly efficient in the diagnosis of cholangitis that often accompanies cholecystitis (Figure 3). As far as we are concerned, there is no published study regarding DWI features of cholangitis complicating acute cholecystitis.

Figure 3. A 37 y old female patient with acute cholangitis complicating acute cholecystitis. (A and B) DWI with b value of 500 s/mm2 shows increased signal intensity of the wall of biliary tree (arrow); (C) ADC map shows restricted diffusion of gallbladder wall compatible with acute cholangitis and cholecystitis, respectively.

In the study group, there were 20 patients with acute pancreatitis. Sixteen patients with NECT and 19 patients with combined imaging were correctly diagnosed as acute pancreatitis. In these patients, mild forms of pancreatitis were just confirmed with laboratory analysis (e.g. amylase, C-reactive protein, white blood cell count), while in complicated patients either CECT or contrast-enhanced MRI was performed for final diagnosis. Of 26 patients with acute pancreatitis, 24 were diagnosed correctly with CECT in control group. Combined imaging could show all of 5 severe forms and complications of pancreatitis (3 necrosis and 2 abscess), while NECT found 2 complications (abscess). The present study showed that features related to pancreatitis such as edema, abscess and necrosis could be easily assessed with DWI. Studies in the literature show that there is no difference between DWI and CT in diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. DWI clearly delineates the pathology even more than CT does [22]. Our results were in concordance with the literature.

Except for four, 20 patients with acute diverticulitis were correctly diagnosed at NECT and all 24 acute diverticulitis were correctly diagnosed at combined method in our study. All of 28 acute diverticulitis were diagnosed correctly with CECT in control group. All patients underwent colonoscopy following antibiotic therapy to rull out malignancy. Combined imaging found all 7 complications (5 abscess and 2 perforations) while NECT diagnosed only 2 abscesses and one perforation. All of the complicated patients in the study group were confirmed either by CECT or contrast-enhanced MRI. CECT could find all complications (8 abscesses and 3 perforations) in the control group. CT is usually needed for the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis and the sensitivity ranges from 60% to 97% [23]. In a study of 30 patients, the sensitivity of CT and DWI in diagnosis of diverticulitis was reported as 93% and 100%, respectively [24]. Furthermore, DWI might be better at differentiating between colon cancer and diverticulitis [24]. DWI might also be able to give information about complications such as perforation or abscess of acute diverticulitis similar to contrast-enhanced sequences and restricted diffusion region indicates these complications [25]. Our results were compatible with the literature.

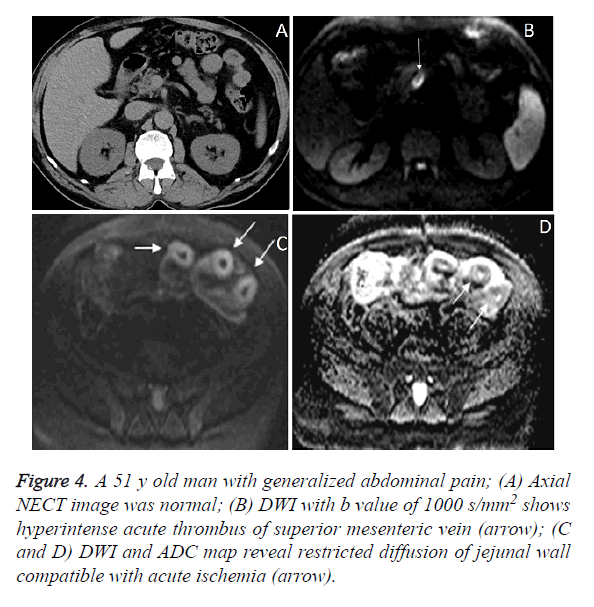

Contrast-enhanced CT and MR angiography are routinely used to establish the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia. Bowel ischemia can be detected with CT when advanced and irreversible damage has already occurred. It is stated despite the fact that contrast-enhanced CT angiography is able to clearly show superior mesenteric artery occlusion of the proximal segment, it fails to diagnose non-occlusive ischemia. Although few studies on the use of DWI in Superior Mesenteric Artery (SMA) occlusion as a cause of mesenteric ischemia have been reported, no study regarding DWI findings in venous type mesenteric ischemia has been reported in the literature [26]. DWI is helpful for early diagnosis of occlusive or non-occlusive acute mesenteric ischemia [26]. In our study, there were nine patients with intestinal ischemia due to four superior mesenteric artery and five superior mesenteric vein occlusion. One patient with NECT and eight patients with combined imaging were correctly diagnosed as intestinal ischemia. Only one patient with venous type of ischemia could not be diagnosed with DWI due to excessive motion artifacts. Combined imaging not only showed the acute thrombus but also clearly depict the ischemic changes of bowel (Figure 4). All of these diagnoses were later confirmed by either CECT or contrast-enhanced MRI. Of 8 patients with intestinal ischemia (5 superior mesenteric artery and 3 superior mesenteric vein occlusion), all could be diagnosed correctly with CECT in control group. As a complication of mesenteric ischemia, NECT could predict concomitant bowel necrosis in one, and combined imaging in all four, while CECT knew in three of four patients. We propose that DWI can help in the diagnosis of both types of ischemia as well as aid in the diagnosis of nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia when contrast use is contraindicated.

Figure 4. A 51 y old man with generalized abdominal pain; (A) Axial NECT image was normal; (B) DWI with b value of 1000 s/mm2 shows hyperintense acute thrombus of superior mesenteric vein (arrow); (C and D) DWI and ADC map reveal restricted diffusion of jejunal wall compatible with acute ischemia (arrow).

At low b-values DWI becomes more similar to T2-weighted image. Hence, the absence of T2 images did not create a problem in our study. We had problems caused by low spatial resolution of diffusion images, low SNR and artifacts related to motion (e.g. respiration, arterial beating and bowel movements). Since DWI does not require any contrast agent and images can be obtained in a short time with ultrafast sequences, we tried to minimize these problems with repeated scanning’s. These ultrafast EPI sequences can collect data within 30-60 ms. Thus, most of the problems related to movement artefacts were eliminated. Problems with low spatial resolution of DWI restricted the appearance of anatomical details in most of the images, especially at high b-values (e.g. 1000 s/mm2) in which SNR decreases. We therefore used low b-value (e.g. 0 or 500 s/mm2) images in which DWI resembled T2 images, and thus helped visualization of anatomical details. Furthermore, it should be remembered that we used NECT images as basic images that also helped us for anatomical details.

The present study has several limitations. Firstly, there is not enough number of cases belong to some pathologies such as complications related to renal and ovarian cysts, mural bleeding of the gastrointestinal tract, etc. Our study is non-randomized in which unstable patients, patients with poor cooperation, and some common pathologies as the cause of acute abdomen (e.g. uncomplicated urinary stone disease, gastrointestinal perforations) were excluded. Thirdly, since the diagnosis was performed by consensus decision of two radiologists, inter-observer variability was not evaluated. Fourthly, even though DWI is helpful in acute abdominal pathologies and when added to NECT without contrast administration, they provide as much diagnostic accuracy as that of CECT, patients have to be imaged in two different imaging suits. Also, an extra DWI would not be cost effective, as well as the fact that MRI is not available in all institutions and it might not practicle to perform DWI in all causes of acute abdomen. And lastly, we did not include other MR sequences that provide morphological information which could have better identified the lesion borders, especially with the use of IV contrast. However, this inclusion of other MR sequences would go against our aim in this study as we tried to implement the quickest MR method without the use of IV contrast media in emergency conditions. Further studies on the use of different imaging protocols such as fast MR sequences combined with DWI is also required.

Conclusion

CECT is a standard and well-known imaging modality used for evaluation of acute abdomen. In some patient or physician related conditions, non-enhanced imaging might be preferred. At that point, when combined with NECT, DWI may aid in the detection of the inflammatory or infectious focus, and increase the diagnostic accuracy to a level that is comparable with CECT. By this way, the number of additional CECT scans that might be necessary for the eventual diagnosis, might be reduced. Therefore, in some emergency abdominal conditions if NECT will be used, we propose the addition of DWI. Furthermore, we also propose that DWI and new faster MR sequences without the need of contrast agents may take more place in diagnosis of acute abdomen as in acute cerebrovascular disease at emergency settings. This study design is preliminary and further studies with larger patient groups with different b-values are needed to clearly document the effectiveness of DWI.

References

- Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Diagnostic imaging of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am Fam Physician 2015; 91: 452-459.

- Singh A, Danrad R, Hahn PF, Blake MA, Mueller PR, Novelline RA. MR imaging of the acute abdomen and pelvis: acute appendicitis and beyond, Radiographics 2007; 27: 1419-1431.

- Pedrosa I, Rofsky NM. MR imaging in abdominal emergencies. Radiol Clin North Am 2003; 41: 1243-1273.

- Curtin KR, Fitzgerald SW, Nemcek AA Jr, Hoff FL, Vogelzang RL. CT diagnosis of acute appendicitis: imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995; 164: 905-909.

- Friedland JA, Siegel MJ. CT appearance of acute appendicitis in childhood. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997; 168: 439-442.

- Stoker J, van Randen A, Laméris W, Boermeester MA. Imaging patients with acute abdominal pain. Radiol 2009; 253: 31-46.

- Lubarsky M, Kalb B, Sharma P, Keim SM, Martin DR. MR imaging for acute non-traumatic abdominopelvic pain: rationale and practical considerations. Radiographics 2013; 33: 313-337.

- Qayyum A. Diffusion-weighted imaging in the abdomen and pelvis: concepts and applications. Radiographics 2009; 29: 1797-1810.

- Moore WA, Khatri G, Madhuranthakam AJ, Sims RD, Pedrosa I. Added value of diffusion-weighted acquisitions in MRI of the abdomen and pelvis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2014; 202: 995-1006.

- Koh DM, Collins DJ. Diffusion-weighted MRI in body: application and challenges in oncology. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 188: 1622-1635.

- Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D. Separation of diffusion and perfusion in intravoxel incoherent motion MR imaging. Radiol 1988; 168: 497-505.

- Oto A, Zhu F, Kulkarni K, Karczmar GS, Turner JR, Rubin D. Evaluation of diffusion-weighted MR imaging for detection of bowel inflammation in patients with Crohn’s disease. Acad Radiol 2009; 16: 597-603.

- Kwee TC, Takahara T, Ochiai R, Nievelstein RA, Luijten PR. Diffusion-weighted whole-body imaging with background body signal suppression (DWIBS): features and potential applications in oncology. Eur Radiol 2008; 18: 1937-1952.

- Muraoka N, Uematsu H, Kimura H. Apparent diffusion coefficient in pancreatic cancer: characterization and histopathological correlations. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008; 27: 1302-1308.

- Hocaoglu E, Aksoy S, Akarsu C, Kones O, Inci E, Alis H. Evaluation of diffusion-weighted MR imaging in the diagnosis of mild acute pancreatitis. Clin Imaging 2015; 39: 463-467.

- Wang A, Shanbhogue AK, Dunst D, Hajdu CH, Rosenkrantz AB. Utility of diffusion-weighted MRI for differentiating acute from chronic cholecystitis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2015; 44: 89-97.

- Rathod SB, Kumbhar SS, Nanivadekar A, Aman K. Role of diffusion-weighted MRI in acute pyelonephritis: a prospective study. Acta Radiol 2015; 56: 244-249.

- Stoker J, van Randen A, Laméris W, Boermeester MA. Imaging patients with acute abdominal pain. Radiol 2009; 253: 31-46.

- Pickhardt PJ, Lawrence EM, Pooler BD, Bruce RJ. Diagnostic performance of multi-detector computed tomography for suspected acute appendicitis. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154: 789-796.

- Lee NK, Kim S, Kim GH. Diffusion-weighted imaging of biliopancreatic disorders: correlation with conventional magnetic resonance imaging. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18: 4102-4117.

- Türkvatan A, Erden A, Türkoğlu MA, Seçil M, Yener Ö. Imaging of acute pancreatitis and its complications. Part 1: acute pancreatitis. Diagn Interv Imaging 2015; 96: 151-160.

- Millet I, Alili C, Bouic-Pages E, Curros-Doyon F, Nagot N, Taourel P. Journal club: Acute abdominal pain in elderly patients: effect of radiologist awareness of clinicobiologic information on CT accuracy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 201: 1171-1178.

- Levenson RB, Camacho MA, Horn E, Saghir A, McGillicuddy D, Sanchez LD. Eliminating routine oral contrast use for CT in the emergency department: impact on patient throughput and diagnosis. Emerg Radiol 2012; 19: 513-517.

- Ng CS, Watson CJ, Palmer CR. Evaluation of early abdominopelvic computed tomography in patients with acute abdominal pain of unknown cause: prospective randomised study. BMJ 2002; 325: 1387.

- Sala E, Watson CJ, Beadsmoore C. A randomized, controlled trial of routine early abdominal computed tomography in patients presenting with non-specific acute abdominal pain. Clin Radiol 2007; 62: 961-969.

- Bruhn RS, Distelmaier MS, Hellmann-Sokolis M, Naami A, Kuhl CK, Hohl C. Early detection of acute mesenteric ischemia using diffusion-weighted 3.0-T magnetic resonance imaging in a porcine model. Invest Radiol 2013; 48: 231-237.