Research Article - Asian Journal of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences (2016) Volume 6, Issue 59

A G to C mutation in the CRYGD gamma crystallin gene associated autosomal dominant congenital cataract in Calabar

Mary E Kooffreh1*, Roseline Duke2 and Anthony Umoyen1

1Department of Genetics and Biotechnology, University of Calabar, Nigeria

2Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Unit, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, Nigeria

- *Corresponding Author:

- Mary E. Kooffreh

Department of Genetics and Biotechnology, University of Calabar, Nigeria

Accepted on November 2016

Abstract

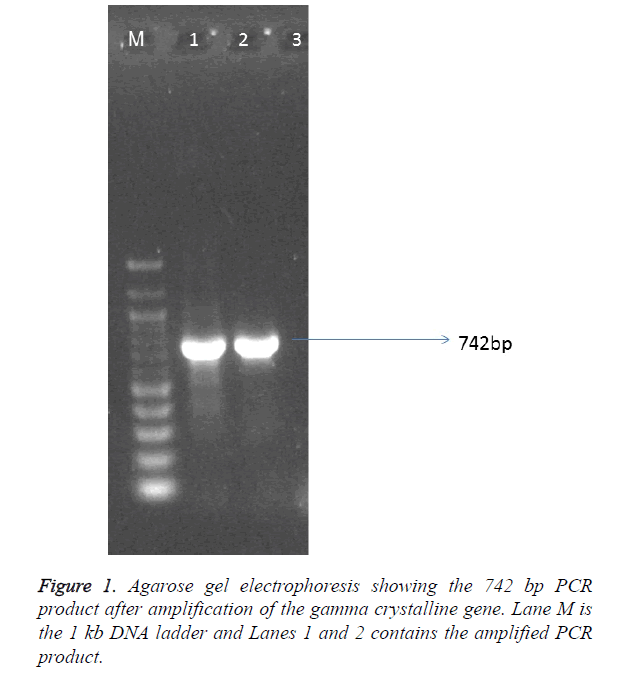

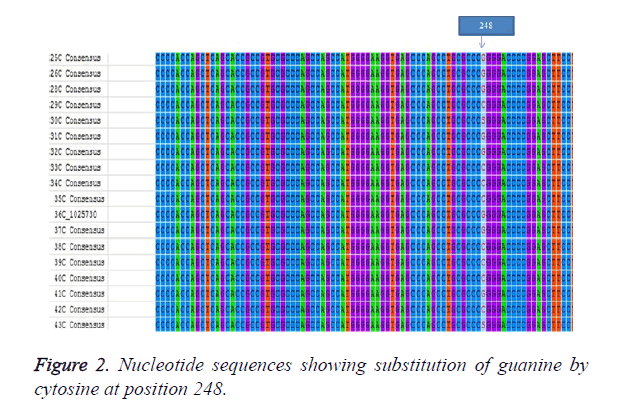

Introduction: Congenital cataract is particularly important as it is the leading cause of blindness and severe visual impairment in children in Africa, accounting for at least 35% of blindness and severe visual impairment. This study seeks to identify mutations in the gamma crystallin gene that are associated with congenital cataract in some children attending the Eye Clinic in Calabar. Methods: Children (11) with congenital cataract attending the University of Calabar teaching Hospital (UCTH) Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus Unit, Department of Opthalmology. 11 unrelated and unmatched controls that had no history of cataract were recruited into the study. 2-3 ml of blood was collected from each child, DNA was extracted from the blood, and PCR amplifications were carried out. About 25 μl of the PCR amplicon was used for sequencing. Multiple sequence alignment and pairwise comparison of the crystallin gene was carried out in the Mega 7 software. Results: The PCR amplication revealed a 742 bp amplicon which was sent for sequencing. In silico analysis revealed a substitution of guanine by cytosine at position 248 (g.248 G>C) that resulted in an amino acid substitution of arginine by proline at position 83 (p.R83P) in 7 (63.63%) out of the 11 patients. This substitution was absent in 4 patients (36.4%) and in the control subjects. Conclusion: This study identified a G>C substitution at position 248 in the crystallin gene in 7 out of 11 congenital patients and this forms a baseline research for further molecular studies among cataract patients in Calabar.

Keywords

Congenital cataract, Crystallin gene, Children, Calabar.

Introduction

Cataract is defined as any opacity of the crystallin lens. Congenital cataract is particularly important as it is the leading cause of blindness and severe visual impairment in children in Africa, accounting for at least 35% of blindness and severe visual impairment [1,2]. Clinically confirmed congenital rubella syndrome is the etiology in about 45% of cases of congenital cataract, 75%forming a heterogenous group of which genetic disorders are included [3]. Congenital cataract may be seen as a primary disorder or it may be associated with other ocular developmental or systemic anomalies. Isolated congenital cataract is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait although autosomal recessive and X linked inheritance are seen less commonly [4].

Progress has been made in identifying genes causing autosomal dominant congenital cataract in developing countries [5]. Two main approaches have been used to identify the causative mutations. Large families linkage analysis has been used to identify the chromosomal locus followed by screening of positional candidate genes; most genes have been identified using this strategy. A second approach has been to screen DNA from large panels of patients with inherited cataract for mutation in the many candidate genes available [6].

In the low and middle income countries, an awareness for the need for genetic studies as a means of improving the clinical management of ocular diseases is increasing. The identification of the genetic mutations and functional studies underlying congenital cataract, suggests an improved understanding of the biology, pathophysiology of the normal lens development and the mechanisms of cataractogenesis in different population groups [7]. This knowledge consequently may improve the understanding of the genetic sequence variants that confer an increased risk of developing age related cataract, which is the leading cause of adult blindness in Africa [8-10]. This may also hold the key to developing a medical treatment for age related cataract [6]. Over twenty of the genes identified so far have been implicated in the development of cataract, majority of these genes code for different crystallins that include the gamma crystallin (CRYGD). Many studies have reported various mutations in the CRYGD gene and association with juvenile onset cataract [11], congenital coralliform cataract [12], nuclear cataract [13] and other forms of cataract [14-18]. In mice also, mutations in the CRYGD gene has been implicated in the development of dominant congenital cataract (18.33) Wang et al., [19] identified c.110 G>C mutation in exon 1 that were implicated in the development of congenital cataract among Chinese families. Crystallin genes encode about 90% of the water soluble structural proteins in the crystallin lens making them appealing candidate genes for studies on congenital cataract [20]. So far no molecular studies have been carried out among Nigerian congenital cataract patients to understand the molecular basis of the disease.

This study seeks to ascertain the molecular basis of cataract thereby contributing to the increasing pool of knowledge in human ocular genetics for Africa. Also to identify any mutations present in exon 1 of the CYRGD gene that may implicated in the development of congenital cataract among Nigerian as baseline for subsequent molecular studies.

Materials and Methods

The study sample population were children who had pediatric cataract surgery between January 2011 and December 2012 in the Calabar Childrens Eye Center, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital (UCTH) Department of Opthalmology. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Calabar teaching hospital, Calabar. Pediatric cataracts were divided into two; congenital and developmental cataracts. Congenital cataract was defined as cataract that developed within the first year of life or cataract associated with the signs of poor fixation signifying early onset. Developmental cataract was defined as a cataract that developed after the first year of life. From the clinical history and chart review, 11 children with pediatric cataracts were found to have a positive family history of a parent or relation having cataract in childhood or early adulthood. Blood samples (2-3 ml) were collected from the children of into EDTA bottles and stored at-20°C for molecular analysis. Children who came for routine eye examinations with no history of cataract were recruited as 11 unmatched controls. PCR and DNA extraction was carried in the Virology unit, International Institute for Tropical Agriculture, IITA, Ibadan Nigeria.

DNA was extracted as previously reported in Kooffreh et al. [21] with slight modifications, 1% monothioglycerol and the tubes were kept in the freezer (-20°C) for 10-20 minutes after the addition of cold isopropanol. PCR amplifications were performed in 50 μl cocktail containing 4 μl of template DNA, 10 μl of PCR buffer, 3 μl of MgCl2, 1.0 μl of dNTPs, 1.0 μl of primer each, 29.76 μl of double distilled water (DDH2O) and 0.24 μl of tag DNA polymerase. The primers sequences are as follows:

F GAGAGAATGCGACCAAAACC

R GCTTATGTGGGGAGCAAACT Wang et al. [11]

Cycling conditions

Initial denaturation step at 95°C for 3 minutes. Then 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 minute, annealing at 58-62°C for one minute, and elongation at 72°C for one minute. Then a final extension step of 10 minutes at 72°C. About 5 μl of the PCR products was checked on agarose gel electrophoresis for PCR amplification of Forward and Reverse primers from exon 1. The protocol for purifying the amplicons was carried out according to Bejjani et al. [22] protocol. 75 μl of ethanol (95%) was added to eppendorf tubes containing 30 μl of the PCR amplicons and inverted 3-5 times. The tubes were then transfered into -20°C freezer for 1 hour. The tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 rcf for 10 minutes. The supernatant was decanted gently and 500 μl of cold 70% ethanol was added, centrifuged again at 12,000 rcf for 5 minutes. Then the alcohol was decanted and tubes air dried at room temperature until no traces of alcohol was seen. The purified amplicon was resuspended in double distilled water and stored in the freezer until transportation to DNA sequencing Facility, USA. About 25 μl of the DNA was used for sequencing. Multiple sequence alignment and pairwise comparison of G to C crystallin gene was carried out in the Mega 7 software.

Results

Demographic analysis

The sample population consist of 11 clinically diagnosed congenital cataract by opthalmologist at UCTH and Elim eye hospital, Cross River State, Calabar. The mean age of the patients was 19.6 ± 1.99. Children with bilateral cataract were 4 and 6 children had unilateral developmental cataract. The patients were 5 males and 6 females but the mutation was observed in 4 males and 3 females. The controls were 6 females and 5 males with the mean age of 5.91 ± 0.89 as shown in Table 1. The PCR amplication produced a 742 bp PCR product (Figure 1), the PCR product was sent for sequencing. After sequencing, in silico analysis revealed 7 (63.63%) out of 11 patients had the g.248 G>C substitution (Figure 2) in the gamma crystallin gene that lead to an amino acid substitution of arginine by proline at position 83 p.R83P. This gene mutation was absent in the remaining 4 patients 36.4% and controls.

| Variables | Patients | Controls | Χ2 | d.f | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean age | 19.6 ± 1.99 (Months) | 5.91 ± 0.89 (Years) | 0.66 | 21 | 0.92 |

| Gender | Total | 5 Males:6 Females | 6 Males:5 Females | 0.43 | 1 | 0.62 |

| With mutation | 4 Males:3 Females | NIL | ||||

| Positive family | 11 | NIL | ||||

| History | ||||||

| Opacification | Nuclear | 10 (90.90) | NIL | |||

| Discrete fine | 1 (9.09) | |||||

| Crystals | ||||||

| Type of bilateral | Congenital | |||||

| Cataract | Cataract | 4 (36.36) | NIL | |||

| Developmental | ||||||

| Cataract | 7 (63.63) | NIL | ||||

Table 1. Showing demographic details of the study population.

Discussion

There are over twenty-six of the thirty-nine mapped loci for isolated congenital or infantile cataracts. These have been associated with mutations in specific genes [23]. We identified a mutation g.248 G>C mutation among patients with congenital cataract in Calabar resulting in a substitution of arginine by proline at position 83 (pR83P). Wang et al., [11] also found the same substitution of guanine by cytosine but at position 110 (110G>C) also leading to a substitution of arginine by proline (pR36P). It is reported that about half of patients with congenital cataract have mutations occurring in crystallins, about a quarter have mutations in connexins, with the remainder divided among the genes for heat shock transcription factor-4 (HSF4), aquaporin-0 (AQP0, MIP), and beaded filament structural protein-2 (BFSP2). There is often some correlation between the pattern of expression of the mutant protein and the morphology of the resulting cataract [23]. Crystallins are further divided into α, β, γ crystallins which have two domain structures with four ´Greek-key` motifs. Li et al., [20] explains that the unique spartial arrangement and solubility of the crystallins make them play significant roles in the optical transparency and high refractive index of the lens. Any modifications of the crystallins are thought to disrupt their normal structure in the lens thereby causing cataract. In this study 90.90% of children presented with nuclear cataracts which is common and suggests an abnormality of gene expression in early development. Some children did not show this mutation. The g.248 G>C is one of the mutations in exon 1, there is a possibility that other mutations in exon 1 might be involved in development of the disease and mutations in other exons may be implicated in disease development. Wang et al. [19] and Pande et al. [24] have reported that the substitution of arginine by proline changes the solvent accessibility character of the protein making it less soluble, decreasing the charge. The mutant protein was also more prone to crystallization than the wild type human CRYGD protein. The activity of R83P mutation identified in our study in the gamma crystalline gene needs further investigation. This study needs to assessed in a larger population for significant conclusions to be reached.

Conclusion

This study identified a G>C substitution at position 248 in the crystalline gene in 7 out of 11 congenital patients. This research adds to data on the gamma crystalline gene and congenital cataract and also forms a baseline research for further molecular studies among congenital cataract patients in Calabar.

References

- Duke R, Otong E, Iso M, Okorie U, Ekwe A, Courtright P. Leallen S Using key informants to estimate prevalence of severe visual impairment and blindness in children in Cross River State, Nigeria. J AAPOS. 2013; 17: 381-384.

- Gogate P, Kalua K, Courtright P. Blindness in childhood in developing countries: time for a reassessment? PLoS Med. 2009; 6: e1000177.

- Duke R. Systemic Comorbidity in Children with Cataracts in Nigeria: Advocacy for Rubella Immunization. J Ophthalmol. 2015.

- Francis PJ, Berry V, Bhattacharya SS, Moore AT. The genetics of childhood cataract. J Med Genet. 2000; 37: 481-488.

- Marner E, Rosenburg T, Eiberg H. Autosomal dominant congenital cataract: morphology and genetic mapping. Acta Opthalmol. 1989; 67: 151-158.

- Moore AT. Understanding the molecular genetics of congenital cataract may have wider implications for age related cataract. 2016.

- Hejtmancik JF. Congenital cataracts and their molecular genetics. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008; 19: 134-149.

- Kyari F, Gudlavalleti MV, Sivsubramaniam S, Gilbert CE, Abdull MM, Entekume G, Foster A. Prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in Nigeria: the National Blindness and Visual Impairmnet Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 2033-2039.

- Abdull MM, Sivasubramaniam S, Murthy GVS, Gilbert C, Abubakar T, Ezelum C, Rabiu MM. Causes of Blindness and Visual Impairment in Nigeria: The Nigeria National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 4114-4120.

- World Health Organization. Visual impairment and blindness. Facts Sheet No 282.

- Stephan DA, Gillanders E, Vanderveen D, Freas-Lutz D, Wistow G, Baxevanis AD, Robbins CM, VanAuken A, Quesenberry MI, Bailey-Wilson J, Juo S-HH, Trent JM, Smith L, Brownstein MJ. Progressive juvenile-onset punctuate cataracts caused by mutation of the gamma-Dcrystallin gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999; 96: 1008-1012.

- Yang G, Chen Z, Zhang W, Liu Z, Zhao J. Novel mutations in CRYGD are associated with congenital cataracts in Chinese families. Scient Rep. 2016; 6: 18912.

- Santhiya ST, Shyam Manohar M, Rawlley D, Vijayalakshmi P, Namperumalsamy P, Gopinath PM, Löster J, Graw J. Novel mutations in the gamma-crystallin genes cause autosomal dominant congenital cataracts. J Med Genet. 2002; 39: 352-358.

- Zenteno JC, Morales ME, Moran-Barroso V, Sanchez-Navarro A. CRYGD gene analysis in a family with autosomal dominant congenital cataract: evidence for molecular homogeneity and intrafamilial clinical heterogeneity in aculeiform cataract. Mol Vis. 2005; 11: 438-442.

- Gu F, Li R, Ma XX, Shi LS, Huang SZ, Ma X. A missense mutation in the gamma D-crystallin gene CRYGD associated with autosomal dominant congenital cataract in a Chinese family. Mol Vis. 2006; 12: 26-31.

- Plotnikova OV, Kondrashov FA, Vlasov PK, Grigorenko AP, Ginter EK, Rogaev EI. Conversion and Compensatory Evolution of the-Crystallin Genes and Identification of a Cataractogenic Mutation That Reverses the Sequence of the Human CRYGD Gene to an Ancestral State. Am J Hum Genet. 2007; 81: 32-43.

- Santana A, Waiswol M, Arcieri ES, Cabral de Vasconcellos JP, Barbosa de Melo M. Mutation analysis of CRYAA, CRYGC, and CRYGD associated with autosomal dominant congenital cataract in Brazilian families. Mol Vis. 2009; 15: 793-800.

- Graw J, Neuhäuser-Klaus A, Klopp N, Selby PB, Löster J, Favor J. Genetic and allelic heterogeneity of Cryg mutations in eight distinct forms of dominant cataract in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004; 45: 1202-1213.

- Wang L, Chen X, Lu Y, Wu J, Yang B, Sun X. A novel mutation in D-crystalline associated with Dominant Congenital cataract in Chinese Family. Mol Vis. 2011; 17: 804-809.

- Li F, Wang S, Gao C, Liu S, Zhao B, Zhang M, Huang S, Zhu S, Ma X. Mutation G61C in the CRYGD gene causing autosomal dominant congenital coralliform cataracts. Mol Vis. 2008; 14: 378-386.

- Kooffreh ME, Anumudu CI, Akpan EE, Ikpeme EV. A study of the M235T variant of the angiotensinogen gene ad hypertension in a sample population of Calabar and Uyo, Nigeria. Egyptian J Med Human Gen. 2012; 14: 13-19.

- Bejjani BA, Lewis RA, Tomey KF, Anderson KL, Dueker DK, Jabak M, Astle WF, Otterud B, Leppert M, Lupski JR. Mutations in CYP1B1, the gene for cytochrome P4501B1, are the predominant cause of primary congenital glaucoma in Saudi Arabia. Am J Hum Genet. 1998; 62: 325-333.

- Francis PJ, Berry V, Bhattacharya SS, Moore AT. The genetics of childhood cataract. J Med Genet. 2000; 37: 481-488.

- Pande A, Pande J, Asherie N, Lomakin A, Ogun O, King J, Benedek GB. Crystal cataracts: human genetic cataract caused by protein crystallization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001; 98: 6116-6120.