Review Article - Journal of Public Health and Nutrition (2018) Volume 1, Issue 2

A critical assessment of the impact of conformity on collectivist families meal social interaction behaviour in Sierra Leone

Sheku Kakay*Department of Management, Leadership and Organisation, Hertfordshire Business School, University of Hertfordshire, United Kingdom

- *Corresponding Author:

- Kakay S

Senior Lecturer

Department of Management, Leadership and Organisation

University of Hertfordshire

United Kingdom

E-mail: s.kakay@herts.ac.uk

Accepted April 10, 2018

Citation: Kakay S. A critical assessment of the impact of conformity on collectivist families’ meal social interaction behaviour in Sierra Leone. J Pub Health Catalog. 2018;1(2):25-38.

DOI: 10.35841/public-health-nutrition.1.2.25-38

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Public Health and NutritionAbstract

Background: Conformity is sanctioned at Sierra Leonean families’ mealtimes not only to streamline behaviour, but also to overhaul the character of individuals in order to increase their acceptance in society. These norms are reinforced to promote appropriate ethical standards at mealtimes. Consequently, moral family education at mealtimes is fundamental for knowledge transfer and for instilling appropriate discipline in children. The importance of this is that it plays a critical part in refining the thoughts of individuals within a family at mealtimes, which enables them to understand their roles and positions in the family and their relationship with others within and without the family, especially visitors and extended family members. Thus, building relationship with other members of the family is a mandatory requirement at mealtimes, as it serves to foster continuity and the long-term survival of the family. Tacitly, family cohesion is central to how families relate with each other at mealtimes and acts as a critical determinant of the degree of closeness in a family, which is vital for the families’ public image. Methods: The researcher used one-to-one semi-structured qualitative interviews to investigate families’ views and experiences of their mealtimes’ behaviours. In this research, due to the fact that the selected samples of families were unknown, the researcher used snowballing; convenience; and experiential sampling in recruiting respondents, including males and females from different cultural, ethnic, religious and professional backgrounds, across the different regions of Sierra Leone. The interviews were guided by a topic, and this procedure was followed until no new themes emerged. The interviews were recorded using an audio recorder, which were transcribed verbatim and analysed using a thematic approach. Results: A total of 20 families (comprising 20 husbands and 20 wives) with a sample size of 40 participants were used in this study. The paper highlights the influence of conformity on the behaviour of Christian and Muslim families (husband and wife) at mealtimes and draw attention to its significance as influencer of collectivism, particularly in relation to its impact on the social interaction between similar and dissimilar gender groups. The author critically assessed the extent of the influence of conformity on families’ meal social interaction behaviour and presented a comparative analytical summary of how gender affects the meal behaviours of different gender and religious groups. Conclusion: The aspect of conformity, as emphasised by a majority of the respondents, is used to not only reinforce family norms, beliefs and values, but to imbibe discipline among family members at the dinner table.

Keywords

Culture, Conformity, Norms, Family/Consumer behaviour, Social interaction, Collectivism

Background

Sierra Leonean mealtimes are dominated by norms and the expectations from individuals to conform to expected cultural and traditional practices when socialising at mealtimes. This argument is in harmony with the views of Lineburg and Gearheart and Merrill et al. who suggested that family mealtime, are critically important for creating familial bonds, socialisation of behavioural norms and teaching life skills [1-3]. Merrill et al. reiterated that family meal social interaction behaviour at dinnertime is a cornerstone of family life across multiple cultures [2]. A number of researchers have examined family meal social interaction behaviour at mealtimes and posited that most families focuses on a variety of conversational goals and child outcomes, including emotion regulation, well-being, and narrative skills [4-6].

Merrill et al. noted that one of the most evident goals of family meal social interaction at dinnertimes involves socialisation of politeness routines and behavioural norms [2]. This view is also supported by Koh and Wang; Merrill et al. and Segrin and Flora, who suggested that family meal social interaction behaviour at dinnertime is an important site for the sharing of stories of one's day and the shared family past [2,7,8]. In comparison, other researchers have pointed out that family mealtimes are a site for teaching children general knowledge about the world around them and inculcating basic family norms into them [9,10]. These behavioural practices are predominant in the Sierra Leonean society, although there are good reasons to speculate that family meal social interaction behaviour may differ from social group to social group based on their group norms and traditions.

Rhodes et al. and Turner et al. viewed the descriptive norm construct as the children’s perception of preferences (as liking in the attitude construct) of their parents in the same way as group norms within the theory of planned behaviour [11,12]. A study of meta-analysis by Cairns et al. demonstrated that a small but significant correlation exists between parents’ and their children’s food preferences [13,14]. Cairns et al. noted that parents or the person in the family responsible for family meals often prefer healthy and nutritional food. However, taste seems to be preferential for children than nutrition when making food choices [15-17]. Contrarily, the aspects of choice and preferences as a socialisation norm are limited in the meal social interaction behaviour of most Sierra Leonean families. This is because of the increased absence of variety in most Sierra Leonean homes, which hampers their ability to make choices, as they are condemned to what is available at the dinner table.

Sierra Leoneans learn the norms, attitudes and values from their families as part of their socialisation. The effect of the family on people’s socialisation is termed intergenerational influence [18,19]. Of all cultural conventions that structure the daily life in the family meal social consumption domain, the most important is the eating habits [20-22]. Driver et al. purported that food is a substance; providing both physical nourishment and a key form of communication that carries many kinds of meanings [23]. There has been an increasing social and spatial polarisation in Sierra Leone between the ‘haves’ and ‘havenots’, often found in economically poor areas or ghettos where segregation is based predominantly along the lines of class and ethnicity [24,25]. Hilbrecht et al. noted that consumption stands at the intersection of different spheres of everyday life between private and public, the political and personal, the social and the individual, which is very evident in Sierra Leone [26].

It can be argued based on the views of many researchers that, there is little or no empirical evidence, models or frameworks to explain the impact of conformity on collectivist families’ meal social interaction behaviour [27-29]. Therefore, this research attempts to bring empirical data that provides evidence on the conceptualisation of conformity and its corresponding influence on family meal social interaction behaviour in the Sierra Leonean collectivist context. It is against the backdrop of this argument that the researcher sought to determine the conformity factors that influence Sierra Leonean families’ meal consumption behaviour.

Methods

The researcher conducted one-to-one semi-structured face-toface qualitative interviews with families about the conformity factors that influenced their meal social interaction behaviour. This allowed families from different ethnic backgrounds, based on their perspective and own words elucidate their views of the food conformity attributes that influences their meal social interaction behaviours. The researcher during the semi-structured interviews introduced a theme and allowed the conversation to develop according to cues taken from what respondents said about their families (Table 1).

| Interviews with Families | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature | Questions | Field Themes | Sub-themes |

| Conformity | What is the importance of togetherness in your family’s meal social interaction behaviour? | Education | Discussion forum, solution forum, rights and wrongs, reflection, sharing ideas (MW, CW, MH, CH), confidence building (CW, CH), knowledge, family lineage, learning forum, communication family history, experience, share stories, awareness, food ethics (MW), troubleshooting (MW, CWMH, CH), reflectivity (MW), Tradition/values (MH) |

| Family cohesion | Love, care, sympathy, happiness, bonding (CH), unity/cohesion (MW, CW, MH, CH), patience, tolerance, harmony, cooperation (MH), smooth relationship, honesty, cordiality, close ties, peace, happiness, affection (MW, CW, MH, CH), companionship (CW), sense of belonging (CW), friendliness, reduction (CH) | ||

| Family development | Family growth, family enhancement, progress, planning (MH), sustainability, prayer (MW, CH) | ||

| Authority | Respect (MW, CW, MH, CH), control (CW,CH), contentment, good behaviour, fairness, responsibility (CW), behaviour regulator, corrections, boundaries, self-discipline | ||

| Meal Participation | Appetite, absences, socialisation | ||

| What is the importance of obedience in your family’s social interaction at the dinner table? | Authority | Obedience, respect (MW, CW, MH, CH), comportment, boundaries, instruction, submissive, control, rules, orders, command, family head, correct behaviour, incentive/rewards (MH), provision, greeting, contribution (CH), normality, discipline, punitive measures, position, decision-making (MH), protection (CH), confidence (CH), authority (MW, CW, MH, CH), gratifying parents (MW) | |

| Responsibility | Learning curve, image building, raises awareness, expectation, contentment, cooperation, family image (MH), role definition, character definition, God fearing (MW), responsibility (MW, CW), moral ethics (CW), God’s word (MH) | ||

| Family unity | Love (CW), care, stability/unity/cohesion (MW, CW, MH, CH), appreciate, acceptance, togetherness, humility (CW), build relationship, happiness, sympathy, peace, patience, modesty (CH), understanding, cooperation, affection (MH), cultural norm (CH) | ||

| Direction | Guidance, communication (CH), benchmarking, shape behaviour, steering, role definition, conflict resolution, behavioural code, advice (CW), best practices, cultural/traditional beliefs (MW, MH), avert accident (CW) | ||

| Success | Blessings, achievement, upbringing, progress/success (MW, CW, MH, CH), sacrifice, longer lifespan (CW), prosperity, eternal life, perseverance, development, family growth, survival | ||

| What sort of conformed behaviour is expected from members of your family when interacting at the dinner? | Food ethics | Quietness (MW, CW, MH, CH), gratifying parents, wash hands (MW, CW, MH, CH), hygiene (MW, CW, MH, CH), food wastage, anti-social behaviour, left-hand forbidden (MW, CW, MH, CH), food boundaries, sitting posture | |

| Affection | Politeness (CW, MH, CH), sharing (CH), bedience, listening, sense of belonging, hospitality | ||

| Authority | Respect (MW, CW, MH, CH), acceptance, correct behaviour, control, instructions, corrective measure, boundaries (CH) | ||

| Family religious beliefs | Prayer (CW, MH, CH), food type, religion, superstitious beliefs, family religious beliefs (MW) | ||

| Moral education | Advice (MW), learning forum, social norms, good manner, timeliness, comportment, meal covering, moral education (MW, CW) | ||

| How does meal sharing affect your relationship with other people outside your home? | Affection | Love (MW, CW, MH, CH), sharing/affection (MW, CW, MH, CH), respect (MW, CW, MH, CH), affordability (MW, CW), commonality, support, jealousy (CH), resentment, mingling, greed (MH), backbiting, Divulge secret (MH), kindness, gesture, satisfaction (MH), caring (MH), charity (MW, CW, CH), religious beliefs (MW), survival (CH), conflict (CH), word of God (CH) | |

| Relationship building | Cordiality, friendliness, bonding, understanding, friendship, image building (MW, CW), closer ties/unity (MW, MH), admiration/ appreciation (MW, CW, MH, CH), gap bridging, likeness, relationship building (MW, CW, MH, CH), blessing (MW) | ||

| Unity | Togetherness, eating together, happiness (MH), oneness, coordination, collaboration, protection (MH), sense of belonging (CH), cooperation (CH) | ||

Table 1: Thematic analysis and schematic summary diagrams of the impact of conformity on families’ meal social interaction behaviour.

Participants and recruitment

The researcher used snowballing; convenience; and experiential sampling to recruit families from different ethnic backgrounds from across the four regions of Sierra Leone, including the northern, southern and eastern provinces as well as the western area. The researcher primarily focused on urban areas, particularly the provincial headquarter towns with about 20% of the families selected in the North (Makeni), 20% in the South (Bo), 20% in the East (Kenema), and 40% in the Western area (Freetown). This implies that, 4 families were recruited in the North (Makeni), 4 in the South (Bo), 4 in the East (Kenema), and 8 in the Western Area (Freetown). A Sample representation and demographic information of families, who participated in the face-to-face semi-structured interviews, are presented in the table (Table 2). A total of 20 families (20 husbands and 20 wives), a sample size of 40, from various households were contacted across the country with a vivid explanation given to them about the study including potential risks of data publication, benefits to the country generally, and the assurance of confidentiality. The main participants in the study were husbands and wives (married couples) from different ethnic and religious backgrounds. The researcher ensured that an even religious representation was selected for the interviews with ten families from each of the denominations (Muslim and Christian). The husbands and wives were interviewed separately to avoid any biasness or to prevent one couple influencing the other. Consequently, twenty families (20 Husbands and 20 wives) were interviewed with 50% from each denomination (Muslim and Christian). Initial appointments and participant invitation letters; the research themes to be covered; and the participant information sheet detailing the interview protocol, commitment, benefits; and risks and confidentiality were issued to the interviewees at their various places of work before the official scheduled interviews at their homes.

| Families | Demographic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family 001 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: procurement office | ||

| Ethnicity: Creole | |||||

| Family size: 3 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Banker | |||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 3 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Family 002 | Wife | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Businesswoman/self-employed | ||

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Constructor | |||

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Family 003 | Wife | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Nurse | ||

| Ethnicity: | |||||

| Yalunka | |||||

| Family size: 12 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Teacher | |||

| Ethnicity: Kono | |||||

| Family size: 12 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Family 004 | Wife | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Geologist | ||

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||||

| Family size: 7 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Banker | |||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 7 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Family 005 | Wife | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Businesswoman/self-employed | ||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Police Officer | |||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Family 006 | Wife | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Teacher | ||

| Ethnicity: Kono | |||||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Civil servant | |||

| Ethnicity: Kissy | |||||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Family 007 | Wife | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Businesswoman/self-employed | ||

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Finance Officer | |||

| Ethnicity: Kono | |||||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christianity | |||||

| Family 008 | Wife | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Social worker | ||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 10 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christian | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ02 | Type of occupation: Social worker | |||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 10 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christian | |||||

| Family 009 | Wife | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: mid-wife | ||

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: SP | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Businessman/self-employed | |||

| Ethnicity: | |||||

| Madingo | |||||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Family 010 | Wife | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Teacher | ||

| Ethnicity: | |||||

| Koranko | |||||

| Family size: 10 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Civil engineer | |||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 10 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Family 011 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Teacher | ||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Civil servant | |||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Family 012 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Teacher/Pastor | ||

| Ethnicity: Limba | |||||

| Family size: 6 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christian | |||||

| Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Lecturer | ||||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 6 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christian | |||||

| Family 013 | Husband | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Nurse | ||

| Ethnicity: Creole | |||||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Lecturer | ||||

| Ethnicity: Limba | |||||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Family 014 | Wife | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Teacher | ||

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christian | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ03 | Type of occupation: Agricultural Officer | |||

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||||

| Family size: 5 | District/Provincial headquarter town: NP3 | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christian | |||||

| Family 015 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: University Administrator | ||

| Ethnicity: Creole | |||||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christian | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: University Administrator | |||

| Ethnicity: Creole | |||||

| Family size: 4 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: | |||||

| Christian | |||||

| Family 016 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Principal | ||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Deputy Director (Civil Servant) | |||

| Ethnicity:Yalunka | |||||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Family 017 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Businesswoman/Self-employed | ||

| Ethnicity: Temne | |||||

| Family size: 9 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Medical Lecturer | |||

| Ethnicity: Fullah | |||||

| Family size: 9 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Family 018 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Teacher | ||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Businessman/self-employed | |||

| Ethnicity: | |||||

| Madingo | |||||

| Family size: 8 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Family 019 | Wife | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Housewife | ||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 12 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ01 | Type of occupation: Civil servant (Deputy Director General) | |||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 12 | District/Provincial headquarter town: WA | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Family 020 | Wife | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Social worker | ||

| Ethnicity: Mende | |||||

| Family size: 3 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

| Husband | Location: HQ04 | Type of occupation: Social worker | |||

| Ethnicity: | |||||

| Madingo | |||||

| Family size: 3 | District/Provincial headquarter town: EP | ||||

| Religion: Muslim | |||||

Table 2: Sample representation and demographic information of families who participated in the face-to-face semi-structured interviews.

Interviews

A guideline was developed for the entire research process, which was followed from the planning phase onto the implementation phase of the research to avoid any incongruity in the research process. The analysis of literature, guided the identification of theories and ideas that were tested using the data collected from the field. This was done in the form of a gap analysis. The researcher used open-ended questions and themes, from which a broad conclusion was drawn. The themes included Social/Group norm, Respect, obedience, meal sharing, Politeness routines, behavioural norms, sharing of stories, silence and authority. The interview for each respondent was scheduled for an hour, but on the average, it lasted between 50 and 55 minutes. The researcher carried out the interviews at the homes of the interviewees with the conversations recorded on a digital audio recorder.

Data analysis

The researcher transcribed all the data verbatim and imported them into NVIVO 10 to facilitate the analysis and coding. An iterative approach of reading and rereading the transcripts, identifying themes and patterns, and comparing across the data was used in analysing the data. Thus, continuity in the coding process helped identify redundancies and overlaps in the categorisation of the scheme, and then grouped both sequentially and thematically. The use of NVIVO 10 facilitated the development of an audit trail through the use of memos, providing evidence of confirmation of the research findings. After collating and coding, the data was summarised and organised by comparing the responses provided by the different family members (husband and wife), and conceptualised the interpretation of each category by each family member, and how they interact with each other. The researcher noted that sometimes, there were variations in responses from different family members, which could have prompted the use of more than one code, which resulted in the building up of different sub-categories. The researcher worked on the categorisation scheme, assignment of codes, and interpreted and reviewed the transcripts independently. Where there were differences in interpretations, commonalities and differences were identified and interpreted appropriately. Therefore, the researcher used triangulation to enhance the credibility of the data. Also, the audio-recordings and associated transcripts (field notes) were transcribed as soon as the researcher returned from the field to avoid unnecessary build-up of information and data and avoid loss of vital information.

Results

The researcher used a sample of 40 respondents, who were between the ages of 18 and 65 years, as participants in the one-to-one semi-structured face-to-face interview. A tabular representation of the sample and personal data are depicted in table (Table-3). The researcher considered the husband and wife (married couples) in each family as the main participants in the interview process. Twenty families (20 husbands and 20 wives) were selected in order to get a balanced response and interpretation of the results, and to reduce biasness to the bare minimum. It was imperative that, after the twentieth family, the data was saturated as the information collected from the 18th, 19th and 20th families (35th, 36th, 37th, 38th, 39th and 40th interviewees) were similar to those stated by earlier respondents.

| Family category | Age (years) | Gender | Occupation | Ethnicity | Luxury food defined | Examples of luxury food |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01FFI | 30 | Female | Procurement officer | Creole | Any special food eaten once in a while | Foo-foo+sauce, cassava leaves, vegetable salad, groundnut stew, krain-krain, potato leaves |

| 36 | Male | Banker | Mende | Costly food normally consumed for comfort | Vegetable salad, shrimps +chips | |

| 02FFI | 35 | Female | Business woman | Temne | Luxury food is anything very expensive | Meat, fish, salad cous-cous, joloffrice, juice |

| 47 | Male | Builder | Temne | They are food we mainly buy from the super markets | Wine, juice, fuits and drinks, biscuits, ice-cream | |

| 03FFI | 32 | Female | Nurse | Yalunka | It is food provided to the family on special occasions | Rose apple, banana, chicken, salad |

| 52 | Male | Teacher | Kono | Those items that the family needs, but not available at all times | Salad, chicken, meat | |

| 04FFI | 46 | Female | Geologist | Temne | It is anything which you buy with an amount that far exceeds what you will spend on normal food | Pizza, grapes, chicken, macaroni |

| 48 | Male | Banker, Director | Mende | The food which the family wants, but it is not available on a daily basis | Pizza, apples | |

| 05FFI | 35 | Female | Business woman | Mende | They are supermarket foods | Hamburger, salad, sandwich, stew and chicken, meat, sweet potatoes |

| 40 | Male | Inspector of police | Mende | It is ostentatious food | Chicken, snacks, mayonnaise, cocoa | |

| 06FFI | 28 | Female | Teacher | Kono | It is a food that is not prepared every day and are special foods prepared for special days | Salad, dessert, joloff, cous-cous,fried rice, fruits |

| 38 | Male | Civil servant (Technical Coordinator) | Kissy | It is the food we do not normally eat, but eat once in a while with the appropriate ingredients | Meat, drinks, salad, rice, wine | |

| 07FFI | 35 | Female | Business woman | Temne | Food that doesn’t get spoilt easily | Vegetables and fruits |

| 39 | Male | Finance Officer (YMCA) | Kono | It is food that has all the nutrients to help the body grow | Ovaltine, cappuccino, milk, sardine, luncheon meat, salad cream, cornflakes | |

| 08FFI | 46 | Female | Social worker | Mende | A food that is not being purchased by everybody | Tin milk, eggs, vegetables, meat, chicken |

| 50 | Male | Social worker | Mende | A food that makes you look special and you can’t do without them | Hamburger, roasted chicken, ice cream | |

| 09FFI | 49 | Female | Mid-wife | Temne | It is when a sauce has good fish and meat as condiment | Joloff, fried rice, cassava leaves |

| 59 | Male | Business man (self-employed) | Madingo | Is food containing protein, vitamins to build the body | Fruits, chicken, fish, meat | |

| 10FFI | 36 | Female | Teacher | Koranko | Food which can make the children grow well | Drinks, apple, fruits, meat |

| 45 | Male | Civil engineer | Mende | Food used almost on a daily basis | Rice, foo-foo, cassava, potato, etc. | |

| 11FFI | 38 | Female | Teacher | Mende | Any food not always available to the family and very expensive | Fruits, ice cream, meat, milk, ovaltine |

| 43 | Male | Civil servant | Mende | One though a staple, but not everybody can afford it every day or cannot afford it as a balanced diet | Rice, fish, meat, palm oil | |

| 12FFI | 52 | Female | Teacher/Pastor | Limba | Expensive foods | Meat, chicken, fish, salad, palm oil |

| 59 | Male | Lecturer | Mende | It is something I eat and get good feeling from | Salad, meat, chicken, fish, rice | |

| 13FFI | 26 | Female | Nurse | Creole | Food that is needed at home for the daily sustenance of the family | Rice and provisions |

| 39 | Male | Lecturer | Limba | Food that goes beyond your normal expenditure | Snacks | |

| 14FFI | 42 | Female | Teacher | Temne | It is food that is very expensive for the family to buy frequently | Salad, drinks, fruits |

| 50 | Male | Agricultural Officer | Temne | Food that the family cannot prepare at home and the ingredients are not locally available. It is well balanced | Pizza, can foods, drinks | |

| 15FFI | 59 | Female | University Administrator | Creole | Very expensive foods that the family eat once in a week | Salad, hamburger, pizza, foo-foo and bitters |

| 64 | Male | University Administrator | Creole | Foods that you don’t eat ordinarily | Ice cream, sausages, bacon, pies | |

| 16FFI | 42 | Female | Principal | Mende | Any food that is expensive for a normal family to buy and it is usually outside the reach of a normal family | Pizza, meat, salad |

| 45 | Male | Deputy Director (EPA) | Yalunka | They are delicacies eaten by the family | Meat, tin food, salad | |

| 17FFI | 35 | Female | Business woman (self-employed) | Temne | Food consume by the family with the right types of condiments | Stew Rice, salad, fruits, meat, chicken |

| 50 | Male | Medical lecturer/tutor | Fulla | It is food that we eat every day at home | Rice and sauce, eba and okra, krain-krain | |

| 18FFI | 43 | Female | Teacher | Mende | It is everything you use as a family, including staple food | Rice, palm-oil, groundnut oil, onion, season, tomato, provisions |

| 52 | Male | Businessman | Madingo | Food we eat in the home infrequently | Salad, fruits, drinks, sandwich | |

| 19FFI | 45 | Female | Housewife | Mende | Food that is purchased outside the home and are normally very expensive | Hamburger, sandwich, fruits |

| 52 | Male | Civil Servant | Mende | Food that the family needs, but can only be provided on an infrequent basis | Meat, fish, drinks, salad | |

| 20FFI | 40 | Female | Social worker | Mende | Food that people buy from restaurants and stores | Milk, chicken, ovaltine, mayonnaise |

| 48 | Male | Social worker | Madingo | Food that is needed by the family, but difficult to buy on a daily because it is expensive | Roasted chicken and meat, salad, provisions |

Table 3: Personal data of families.

Key findings of the study

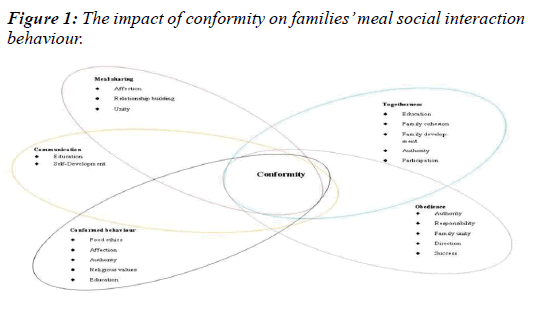

The analysis of this study identified a number of themes and sub-themes, as key ingredients families need to conform to when interacting socially at meal times, including togetherness, obedience, norms, and meal sharing. A comprehensive evaluation and discussion of the influence of each sub-groups on participating males and females was undertaken. The themes and sub-themes that emerged from the study are depicted in the diagram below (Figure 1).

The perceived importance of togetherness

The drive for affection emerged as a key determinant of togetherness among both Muslims and Christian females as part of their families’ meal social interaction behaviour. As the primary preparers of family meals, they agreed that, cohesion is fundamental to their meal social interaction behaviour, as it helps cement relationship and increases the level of bonding between and among family members. In responding to group dynamics, they emphasised idea sharing as pivotal to togetherness, as it increases not only the awareness and knowledge base of the children and young adults, but helps them to learn from parents about families’ past cultural and historic events.

“It is very important. It brings unity in the family, it brings oneness and concern for each other, togetherness ensures that there is a smooth working relationship between every member of the family and provides a forum for sharing ideas”. (Interviewee 9, Female, Christian)

However, it can be justifiable stated that, despite the overwhelming agreement between the pairs, a majority of the Muslim females emphasised respect as an essential ingredient for togetherness, whilst Christian females were less emphatic about its significance in their families’ meal behaviour.

“It makes me feel happy, feel love and feel very special. It is very important to eat together as a family as it is not all the time we eat together as a family. Eating together brings unity and affection in the family”. (Interviewee 1, Female, Christian)The findings also show that Christian and Muslim males predominantly share commonalities about the impact of togetherness on their families’ meal social interaction behaviour. They highlighted family cohesion as central to togetherness at the dinner table, as it visibly helps promote the growth of the family. A majority of the Muslim and Christian males, just as their family counterparts, also discussed idea sharing as fundamental to their families’ meal social interaction behaviour, including unifying the family around a common purpose. Affection was also raised, as an important ingredient to togetherness, as it helps promote the level of empathy and/or sympathy family members have towards each other. For most male participants, eating together at meal times enable them to express concern towards others, reduces the boundary/barrier between family members, and helps parents assess the level of appetite of their children.

“Togetherness is the hub that really propels family growth. Because with togetherness you will disagree to agree, with togetherness you can share and correct each other as you get along. It provides the platform for family affection, enhancement and unity. If you are not together and do not share ideas together, then you will realise that there will be very limited progress in the family”. (Interviewee 8, Male, Muslim)

Despite the avowed similarities between the two denominations, a majority of the Muslim males reiterated that respect is central to their families’ togetherness, which was less emphasised by a majority of the Christian males. It is mostly seen by many Muslim males, as a forum for correcting mistakes, improve the social and table etiquettes of children. For a majority, it teaches children about not only to respect their elders, but also enables them to discern between rights and wrongs in society.

“…Togetherness engenders development and cooperation. A family that sticks together has a greater chance of growing and developing as a unit than one that cares only for themselves and their own goal. Eating together fosters unity and respect in the family and it also enables us to express concern and love for each other”. (Interviewee 36, Male, Muslim)

The importance of obedience

Muslim and Christian female participants described obedience at mealtimes as the primary arbiter for the behavioural guidance of children. Succinctly, many perceived it as the foundation for fostering respect between parents, children as well as other relations. Respecting elders at the dinner table and outside it, acts as the proviso for reciprocating to the needs of younger ones. Obedience at the dinner table was highlighted by many as the cornerstone to authority at mealtimes, as it instils discipline in the children and enables them to follow the instructions and orders of parents. A majority of the participants emphasised authority as the driving force for unity and stability in the family at mealtimes.

“Well, obedience is important as it guides the behaviour of the children and shows them the importance of respecting elders and even their colleagues or brothers and sisters. With obedience, the children can listen to authority and follow the rules set at the dinner table. So obedience in Africa can be viewed as a sign of responsibility and humility. If your children are disobedient, the tendency of them becoming street kids is very great, but a child that obeys has greater chances of succeeding in life because of the blessing he/she would have gotten from the parents”. (Interviewee 33, Female, Muslim)

Despite the overwhelming similarities, a majority of the Muslim females were less emphatic about the love obedience brings in the family and the moral ethics it teaches the children, which was overwhelmingly emphasised by a majority of the Christian females. The Christian female participants argued that, it does not only bring love, stability and growth in the family at mealtimes, but also help guide, teach and direct children how to behave in public.

“It is very important because will bring about other issues such as love between the mom and the children and the dad and the children. It will enhance the relationship among members of the family and teaches the children the norms of moral ethics”. (Interviewee 15, Female, Christian)

In the same guise, Muslim and Christian males shared commonalities in the area of respect, as symbolic value of obedience and the arbiter for the future success of the children. Children deviating from the norms of respecting elders at the dinner table are usually reprimanded, frowned upon, ostracised or punished. Family cohesion also emerged as a common shared value of obedience, and promotes a sense of stability and unity at family meal times. Some of the participants articulated authority as a prime obedience-influencing factor, as it promotes control and adherence to the chain of command at the dinner table.

“It is very critical because it brings respect and decorum, it brings a sense of normality in the family because if the younger ones obey and respect their older siblings, there is some form of control, and there some form of chain of command, that of the father is not there, the younger ones should listen to the eldest. So whatever happens there is always that chain of command even in the absence of the father. As I said, obedience is very critical because it brings decorum and unity because if you obey there will be little room for friction within the family. It is only when nobody listens to each other that chaos will ensue. But if obedience is maintained within the family at the dinner table, it will be very helpful to keep the family in order”. (Interviewee 32, Male, Muslim)

Adherence to conformed behaviour

Multiple Christian and Muslim females described adherence to conformed behaviour as strong persuaders of good food ethics at meal times. Consequently, children are expected to comply and embrace good table manners, and to learn and imbibe good practices, as a way of correcting behavioural anomalies at the dinner table. As a good table manner and etiquette, children should, therefore, respect their parents, keep quiet, respect their elders, say prayers before eating, and say thank you to both parents after eating.

“Respect for each other and for elders, prayers before eating, saying thank you to both parents for the preparation and provision, quietness observed throughout the meal”. (Interviewee 27, Female, Christian)

Invariably, multiple Muslim and Christian males emphasised the significance of observing food ethics as symbolic ingredient of conformed behaviour expected from their families at meal times. Meal times are guided by the observance of appropriate norms such as washing hands before eating, the use of the right hand, and quietness throughout dinner. The resultant effect of non-compliance is reprimand and/or the institution of punitive measures, such as ostracisation from the group. The institution of such practices is to ensure that boundaries are observed when interacting socially, which promote norms and values, around which the families coalesce at the dinner table.

“They are expected to wash their hands, they are expected not to eat with their left hands, they are expected to cover their meal when not eating, they are expected to cover their mouth when coughing, etc.” (Interviewee 16, Male, Christian)

However, a majority of the Muslim males emphasised respect as expected conformed behaviour at mealtimes, which is less emphasised by the Christian males. Therefore, the dinner table is a place, where children can learn to inculcate better behaviour at mealtimes, including politeness, obeying elders and comportment.

“They are all expected to be very respectful, that is the key word, to whosoever that is witnessing that particular dinner in terms of observing the cultural things I made mention of”. (Interviewee 20, Male, Muslim)

The impact of meal sharing

Multitude of Muslim and Christian female respondents argued that, meal sharing brings cordiality, respect and friendship both within the household and without it. It is a way of extending kindness or gesture to the needy, especially those that do not have access to food. Religious and cultural doctrines also largely influence these belief systems, which augment the tendency of sharing meal not only within the household, but also outside it. The drive for unity is highly prevalent among participants, which is an important motivator for meal sharing. Eating in unison can help the family coalesce around a common goal, which has a domino effect on the way the community perceives the family, and largely determines the degree of closeness they enjoy with outsiders.

“It affects my relationship with them positively. It makes them come closer and have affection for my family and they do appreciate the provision I am making for them”. (Interviewee 13, Female, Christian)

“It makes our neighbours and people that we share with love and respect our family and makes them very friendly towards us and our children” (Interviewee 19, Female, Muslim)

In tandem with the views of females, the Christian and Muslim males view meal sharing as a way of building relationship with others. Meal sharing provides the platform for oneness and for bridging the gap between the family and its extended relations, and neighbours. Dinning with others create a sense of belongingness and act as a forum for supporting and sharing ideas with others. It is a way of propagating affection and a sense of peaceful co-existence with people in the community, particularly neighbours. Many argued that, sharing meal helps one understand the problems faced by members of his/her family, neighbours, and people in the community. This, they argued is triggered by religious beliefs, which mandate individuals to share especially with the less privileged in society.

“Inviting people at the dinner table enhances the relationship and it also enables you to know people you have not met before”. (Interviewee 30, Male, Christian)

Conversely, while a majority of the Muslim males emphasised respect as symbolic in meal sharing, a majority of the Christian males, on the other hand, emphasised unity as symbolic in meal sharing. For other individuals, meal sharing with outsiders, who are not part of the family, can have negative consequences by limiting the amount of food accessed by them. It can also serve as the conduit through which the family’s internal secrets, including the quality of meal served at mealtimes. They expressed the avowed concern that, inviting outsiders to low quality meal, can cause the families’ internal problems to be exposed. Consequently, a few participants do not have affinity for sharing food with outsiders due to a number of concerns, including quality, sanity and tidiness of the food prepared.

“The way the food is prepared is important to prompt sharing particularly cleanliness and tidiness. This has been the major problem with sharing, though we think it is important as it brings unity and friendliness. We don’t allow our children to even buy street foods.” (Interviewee 2, Male, Christian)

Discussion

To the researcher’s best knowledge, this is the first study to explore the views of families about the impact of conformity on their meal social interaction behaviour across Sierra Leone. The results of the findings highlight togetherness, including affection, family cohesion and the opportunity it brings the family to share ideas together, as a fundamental perspective of conformity espoused by all religious sects. Despite the symbolism of togetherness across all religious groups, there were dissimilarities between Muslims and Christians, as a majority of the Muslim females and males emphasised respect as central ingredient of togetherness,