Research Article - Biomedical Research (2019) Volume 30, Issue 4

Self-treatment and treatment of close relatives: Prevalence, perceptions and attitudes among primary health care physicians.

Manal Abdulaziz Murad1*, Salem Mohamed Ali Barabie2, Razaz Tawfiq2, Bayan Khaled Mohamad Rashad3, Abdulla Khalid Sagga4 and Banan Khalid Sagga5

1Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2Department of General Practice, King Abdulaziz University Hospital, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

3Department of Science in Health Promotion Management, College of Art and Sciences, American University, Washington DC, USA

4Agency for Primary Health Care, Medical Program for Chronic Diseases, Department of General Medicine, Ministry of Health , Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

5Medical Intern, Ibn Sina National College for Medical Studies, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Dr. Manal Abdulaziz Murad

Department of Family Medicine

Faculty of Medicine

King Abdulaziz University

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Accepted date: March 8, 2019

DOI: 10.35841/biomedicalresearch.30-19-101

Visit for more related articles at Biomedical ResearchAbstract

Background: Self-treatment, treatment of closed relatives and friends compromises the professional objectivity and these are important medical ethical issues that pose big professional challenges to the physicians. Objectives: To assess the prevalence of self-treatment and treatment of close relatives (TCR) among primary healthcare (PHC) physicians and to investigate factors, perceived risks and ethical awareness related to this practice. Methods: This questionnaire-based cross-sectional was study conducted by randomly selecting 15 PHCs in Western region of Saudi Arabia between April and May 2016 at the Family and Community Medicine Department, Medical College, King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Physicians from all specialties replied anonymously to the questionnaire. Results: Eighty PHC physicians were recruited, 52.5% females, 77.6% aged below 40 years; majority were general practitioners (61.3%) with 0-5 years of practice (53.8%). The prevalence (95% CI) of selftreatment, self-prescribing and self-prescribing of controlled substances was 87.5% (80.3; 94.7); 90.0% (83.4; 96.6) and 7.5% (1.7; 13.3) respectively. Prevalence of practices related to TCR ranged from 6.3% for surgery to 93.8% for physical examination performed on a close relative. Sense of responsibility, illness being among scope of practice and minor illness were the three most frequent motivations for TCR. Compromising physician ’ s objectivity, family quarrels and patient to conceal sensitive information were frequently perceived risks for TCR. Regarding ethical awareness, majority of the participants (68.8%) declared not being aware of international guidelines and minority would agree to classify self-treatment and TCR as not recommended. No association was found between practice and demographics or ethical awareness. Conclusion: Self-treatment, TCR and related practices are highly prevalent among PHC physicians in Saudi Arabia despite appropriate perception of associated risks.

Keywords

Ethics, Practice, Self-prescribing, Self-treatment, Treatment, Family

Introduction

Physicians have adequate knowledge, experience and ability to apply the medical care to their family members, friends as well as for self-treatment [1]. It is easy and common for people to solicit a physician relative for medical help, rather than to use the ordinary health care system. Motivations of such inquiry are multiple; and the medical help inquired may be a simple visit or medical advice, but can grow up to an actual therapeutic action ranging from a common prescription to a surgical operation [2]. Growing evidence indicates that personal or close relationships can compromise the physician’s emotional and clinical objectivity, preventing the physician to meet the standards of care, which affects the quality of the treatment [3]. Because of several social and cultural considerations, doctors may find difficulty to refuse care for a family member [4]. On the other hand, when accepting to treat a sick family member, the physician may face conflicting ethical issues that are not always easy to handle. Indeed, acting as a good and devoted relative may be incompatible with acting as a good and competent doctor, and vice-versa. In several situations, the determinants of the two roles (parent and doctor) may be in conflict. In other words, objectivity required in medical exercise is often affected by subjectivity related to the relative role [5].

Therefore, several institutions, such as the British Medical Association (BMA), the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American College of Physicians (ACP) have stated on this issue, advising doctors not to get involved in selftreatment or treating family members [4-6]. These institutions presented a list of risks associated with self-treatment and treatment of close relatives, such as compromised professional objectivity by excess of emotions; which impedes all times of the care procedure. For example, physicians may fail to probe into sensitive areas when taking history or to perform intimate examinations such as pelvic and rectal examination; or they may avoid painful but necessary investigation. On the other hand, most of these consultations are done out of clinical setting without use of appropriate equipment, which usually results into poor or even no physical examination. Further, emotion may prompt the physician to deny some diagnosis because they carry poor prognosis. Moreover, patients may also incur delay in diagnosis and treatment. Another argument was the risk of overtreatment in relation with the physician being anxious to seeing his family member get well quickly. Furthermore, treatment of close relatives may have social consequences which include family quarrels and disunity that may occur if the outcome of treatment is negative [4-6].

In Saudi Arabia, there is no legislation which states on this specific issue. However,

The Saudi Commission of Health Specialties issued a general code of ethics for health professionals which provide only general aspects for respect of patient ’ s autonomy, and confidentiality. This code of ethics also put some light on encouragement of physician’s devotion and proficiency [7,8].

Thus, in absence of clear local ethical guidelines, Saudi physicians’ practice, perception and attitude regarding treating family members may be biased by the social and cultural values, hence medical duty may be confused with the sense of responsibility and moral commitments they have towards family members [9]. However, no evidence about the extent of this practice is available so far.

The current study was aimed to assess the prevalence of selftreatment and treatment of close family members among primary healthcare center (PHC) physicians and to investigate the related practices including social as well as cultural factors. In addition to these factors, this study also focused to investigate the physicians’ perception, attitude about the risks related to these practices. This study also investigated the awareness of PHC physicians about international and national ethical guidelines pertaining to self-treatment and treatment of close family members and friends.

Materials and Methods

Design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted by randomly selecting 15 PHCs in Western region of Saudi Arabia between April and May 2016 at the Family and Community Medicine Department, Medical College, King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). This study was ethically approved by the Medical Research and Studies Department (MRSD), Directorate of Health Affairs-Jeddah, Ministry of Health, Saudi Arabia (Research numer: 673 and approval number: A00339). The guidelines of MRSD comply with the National Committee of Biomedical Ethics guidelines, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and national and international laws and policies of National Institutes of Health, United State of America (USA).

Population and sampling

The study involved PHC physicians working in different specialties including general medicine, family medicine, internal medicine, gynecology, pediatrics and endocrinology. A stratified two-stage cluster sampling method [10] was used to select 3 PHC centers out of each of the 5 PHC sectors (clusters) of Jeddah including North-Eastern, North-Western, Center, South-Eastern and South-Western sectors. Each sector containing 7 to 13 PHC centers for a total of 46. The fifteen selected centers were contacted prior to the data collection to fix an appropriate day for questionnaire distribution. Using a convenience sampling, on the day of the interview, all present physicians were invited to respond to the questionnaire. Target sample size (N=194) was calculated to detect an estimated 68% prevalence of self-treatment (outcome of interest) among 460 physicians with a 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.05 type I error and 80% statistical power [11].

The questionnaire

Data collection used a semi-structured, self-administered questionnaire was developed by the authors and included the following parts:

Assessment of self-treatment and treatment of close relatives including related practices, such as self-prescribing, controlled substances prescribing, performing surgery etc. (10 items).

Assessment of physician’s motivations to treat close relatives, such as feeling sensé of responsibility, urgent care needed, embrassement to refuse etc. (10 items).

Other practices related to treating close relatives, such as implementing appropriate follow-up, fee taking, refusal and eventual reasons to refuse care requests from close relatives (5 possible reasons).

Physician’s perceptions about self-treatment and treatment of close relatives; including perception of related risks with this practice (10 items) [4-6] and attitude in treating specific family members (10 items).

Physician’s awareness about national or international ethical guidelines or recommendations regarding self-treatment and treatment of close relatives, as well as personal opinion about each practice (4 items).

Face and content validity were verified by careful and consensual selection of the items by the co-authors with the concurrence of a methodologist under the light of literature search.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) SPSS (Statistical Package of Social Science) for Windows version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to present demographic and professional characteristics as well as the patterns of answers to the different parts of the questionnaire. Participants were divided into two groups: those who ever practiced self-treatment and/or treatment of close relative, and those who never did. The association of practice with demographic and professional factors as well as with ethical awareness was analyzed using chi-square test. To analyze the effect of risk perception on practice, a risk perception score (RPS: 0-10) was calculated as the number of risks perceived by the physician and compared between the two groups using nonparametric test (Mann-Whitney U test) and presented as median (75th centile [P75]). A p-value <0.05 was considered for statistical significance.

Results

Population characteristics

The study included 80 PHC physicians (response rate=41.2%); Out of these: 52.5% were females; 44.5% were males; 75.0% married; 33.8% aged 20-29 years, 43.8% aged 30-39 years and 22.5% aged 40 and above. Majority were general practitioners (61.3%) and had 0-5 years of practice (53.8%). Distribution in geographic sectors ranged between 13.8% in Center to 26.3% in North-Eastern sector (Table 1).

| Variable | Value | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male Female |

38 42 |

47.5 52.5 |

| Age (years) | 20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 |

27 35 12 6 |

33.8 43.8 15.0 7.5 |

| Marital status | Single Married |

20 60 |

25.0 75.0 |

| Nationality | Saudi Non-Saudi Not specified |

74 5 1 |

92.5 6.3 1.3 |

| Number of children | 0 1 2 3 4 or more |

37 18 8 5 12 |

46.3 22.5 10.0 6.3 14.9 |

| Years of practice | 0-5 5-10 10-15 >15 |

43 16 8 13 |

53.8 20.0 10.0 16.3 |

| Specialty | General Medicine Family Medicine Pediatrics Obstetrics-Gynecology Internal Medicine Other |

49 20 1 2 1 5 |

61.3 25.0 1.3 2.5 1.3 6.3 |

| Sector | North East North West Center South East South West |

21 19 11 17 12 |

26.3 23.8 13.8 21.3 15.0 |

| Dwelling place of most of the family | Same city Another city Outside the country |

65 12 3 |

81.3 15.0 3.8 |

Table 1. Participants’ demographic and professional characteristics.

Practice in self-treatment and treatment of close relatives

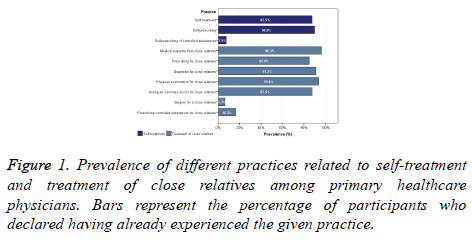

The prevalence [95% confidence interval (CI)] of selftreatment, self-prescribing and self-prescribing of controlled substances was 87.5% (80.3; 94.7); 90.0% (83.4; 96.6) and 7.5% (1.7; 13.3), respectively. Regarding treatment of close relatives, 96.3% of the physicians declared receiving requests from their family members whilst 85.0% declared having already prescribed medications, 93.8% performed physical examination, 91.3% diagnosed an illness and 6.3% performed a surgery on one or more of their close relatives (Figure 1). All the participants (100%) declared having ever practiced at least one of the previous practices related to treating close relatives. Further, 60% (95% CI: 49.3; 70.7) of the participants declared that they have ensured appropriate follow-up to their relatives subsequent to treating them. On the other hand, 8.8% (95% CI: 2.6; 14.9) declared already taking fees for treating a family member.

Perceptions and attitude regarding self-treatment and treatment of close relatives

Perceptions and attitudes including motivations for selftreatment and treating close relatives, refusal attitude, perception of the related risks and ethical attitudes are presented in Table 2. Sense of responsibility was the most frequently reported motivation for treating close relatives (93.8%) followed by other motivations reported by 16.3% to 91.3% of the participants. Among participants, 33 (41.3%) declared that they have ever refused to treat a family member and refusal was justified by referral to a more competent colleague in 41.3%, followed by other reasons such as avoidance of uncomfortable aspects of physical examination in 26.3% and respect of patient’s autonomy and confidentiality in 22.5%. Regarding assessment of risk perception, it has been shown that majority of participants agreed that self-treatment and treatment of close relatives may compromise professional objectivity (72.5%), impede proper record-keeping and appropriate follow-up (67.5%) and cause family quarrels in case of negative outcome (66.3%). Ethical awareness showed that majority of the participants (68.8%) declared not being aware about international guidelines or recommendations related to self-treatment and treatment of relatives while 51.3% declared being not aware whether such guidelines exist in Saudi Arabia. Assessment opinions showed that 26.3% and 31.3% believe that self-treatment and treatment of close relatives should be inadvisable, respectively (Table 2).

| Parameter (Item) | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| What motivated you in treating close relatives? | ||

| Sense of responsibility | 75 | 93.8 |

| Complaint among my scope of practice | 73 | 91.3 |

| Minor illness | 73 | 91.3 |

| Family has priority to benefit from my knowledge | 58 | 72.5 |

| Urgent care needed | 46 | 57.5 |

| I know my family member best | 44 | 55.0 |

| Feeling compelled | 39 | 48.8 |

| Embarrassed to refuse | 36 | 45.0 |

| By principles | 31 | 38.8 |

| Disagreement with physician’s management | 13 | 16.3 |

| Ever refused to treat a close relative? | ||

| Yes | 33 | 41.3 |

| Never | 47 | 58.8 |

| Reasons for refusal* | ||

| Referral to more competent colleague/physician | 31 | 96.9 |

| Avoid uncomfortable aspects of physical examination | 20 | 69.0 |

| Respect autonomy and confidentiality | 16 | 53.3 |

| Avoid uncomfortable aspects of history | 13 | 46.4 |

| Prefer formal visit | 11 | 33.3 |

| Other** | 4 | 12.1 |

| Risk perception about ST and TCR (N, % of participants who agreed with the item being a potential risk) | ||

| Compromise objectivity | 58 | 72.5 |

| Absence of proper record-keeping | 54 | 67.5 |

| Family quarrels in case of negative outcome | 53 | 66.3 |

| Poor or absence of physical examination | 53 | 66.3 |

| Patient to conceal sensitive information | 53 | 66.3 |

| Failure to perform intimate examination | 50 | 62.5 |

| Failure to investigate sensitive history | 49 | 61.3 |

| Over treating | 46 | 57.5 |

| Denial of diagnoses with poor prognosis | 39 | 48.8 |

| Avoidance of painful investigations | 34 | 42.5 |

| Awareness about international ethics or recommendations regarding ST & TCR | ||

| Not aware | 55 | 68.8 |

| Aware | 24 | 30.0 |

| Are there ethical guidelines in Saudi Arabia regarding ST & TCR? | ||

| No | 9 | 11.3 |

| Probably not | 9 | 11.3 |

| I don’t know | 41 | 51.3 |

| Probably | 15 | 18.8 |

| Yes | 5 | 6.3 |

| Self-treatment should be inadvisable | ||

| Do not agree | 43 | 53.8 |

| Agree | 21 | 26.3 |

| No opinion | 16 | 20.0 |

| Treating close relatives should be inadvisable | ||

| Do not agree | 37 | 46.3 |

| Agree | 25 | 31.3 |

| No opinion | 18 | 22.5 |

Table 2. Perceptions and attitude regarding self-treatment and treatment of close relatives.

Percentages are calculated on the number of participants who declared having ever refused to treat a close relative [Number (N)=33]; Other reasons of refusal included: “health issue not in my scope of practice” (1 case), need for specific examination tools (1 case), gynecological problem (1 case), to avoid blame and family quarrel (1 case); self-treatment & treating close relatives (ST & TCR). Reasons for refusal are not mutually exclusive. Some values in the table do not sum up to total (N=80) because of some missing answers in the questionnaires.

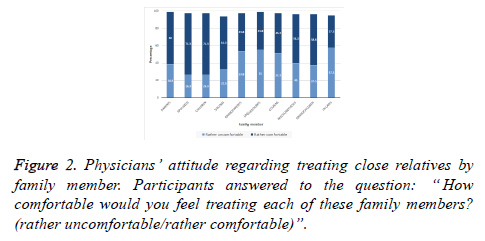

Attitude by specific family member

Family members whose treatment was more frequently perceived as uncomfortable were in-laws (57.5%) followed by uncles/aunts (55.0%), grandparents (53.8%) and cousins (51.3%). Participants reported most frequently being comfortable in treating their spouses (71.3%) and children (71.3%) followed by their parents (60.0%) (Figure 2).

Association of self-treatment with treatment of family members

Self-treatment practice was associated with prescribing for family close relatives; that is physicians who declared practicing self-treatment reported more prescribing for close relatives as compared to those who declared not practicing self-treatment (90.0% versus 50.0%; p=0.005, respectively). However, self-treatment was not significantly associated with the other practices including diagnosing (92.9% versus 80.0; p=0.210), physical examination (94.3% versus 90.0%; p=0.497), acting as family doctor (88.6% versus 80.0%; p=0.605), surgery (5.7% versus 19.0%; p=0.497) and controlled substance prescribing for close relatives (15.7% versus 20.0%; p=0.662). Furthermore, 33.3% of physicians who practiced self-prescribing of controlled substances also prescribed controlled substances to their close relatives as compared to 14.9% who did not practice self-prescribing of controlled substance, however, this result was not statistically significant (p=0.250).

Effect of demographic factors of practice on selftreatment and treatment of close relatives

In chi-square correlation analysis, all of the investigated practices related to self-treatment and treatment of close relatives were equally reported across genders, age groups, marital status, nationality, years of practice, specialties and distance from the family home (chi-square test; p >0.05). Likewise, across sector and across center comparison showed equal distribution of most of these practices except performing surgery and prescribing controlled substances for relatives, both being significantly more reported in some centers/sectors than in the others (p <0.05).

Effect of risk perception on practice

The risk perception score (RPS) was generally greater in participants who did not practice self-treatment and treatment of close relatives as compared to those who practiced it. However, difference in RPS was statistically significant for only practice related to receipt of requests for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment (Table 3).

| Practice | Status (ever practiced?) | RPS (0-10) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |||

| Self-treatment | Yes No |

5.91 7.50 |

3.02 2.32 |

0.127 |

| Self-prescribing | Yes No |

5.99 7.25 |

3.02 2.31 |

0.251 |

| Self-prescribing of controlled substances | Yes No |

6.00 6.12 |

1.79 3.06 |

0.804 |

| Receiving requests for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment | Yes No |

5.99 9.33 |

2.95 1.15 |

0.036* |

| Prescribing for a family member (excluding over-the-counter treatments) | Yes No |

5.87 7.50 |

3.07 1.88 |

0.097 |

| Diagnosing an illness | Yes No |

6.10 6.29 |

3.01 2.75 |

0.993 |

| Performing physical examination | Yes No |

6.03 7.40 |

3.00 2.41 |

0.361 |

| Acting as a primary doctor for a family member | Yes No |

5.99 7.00 |

3.09 1.89 |

0.387 |

| Surgery for a family member | Yes No |

3.60 6.28 |

4.98 2.76 |

0.218 |

| Prescribing a controlled substance for a family member | Yes No |

5.23 6.28 |

1.64 3.15 |

0.107 |

Table 3. Effect of risk perception on practice in self-treatment and treatment of close relatives.

Effect of ethical awareness on practice

Chi-square correlation analysis showed that awareness about international recommendations had no effect on any of the 10 practices related to self-treatment and treatment of close relatives (Table 4).

| Practice | Awareness about international ethical recommendations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not aware (N=55) | Aware (N=24) | p-value | |||

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | ||

| Self-treatment | 49 | 89.1 | 20 | 83.3 | 0.482 |

| Self-prescribing | 40 | 89.1 | 22 | 91.7 | 1.000 |

| Self-prescribing of controlled substances | 4 | 7.3 | 2 | 8.3 | 1.000 |

| Receiving requests for medical advice, diagnosis or treatment | 53 | 96.4 | 23 | 95.8 | 1.000 |

| Prescribing (excluding over-the-counter treatments) for a family member | 47 | 85.5 | 20 | 83.3 | 1.000 |

| Diagnosing an illness | 48 | 87.3 | 24 | 100.0 | 0.094 |

| Performing physical examination | 53 | 96.4 | 21 | 87.5 | 0.161 |

| Acting as a primary doctor for a family member | 48 | 87.3 | 22 | 91.7 | 0.715 |

| Surgery for a family member | 4 | 7.3 | 1 | 4.2 | 1.000 |

| Prescribing a controlled substance for a family member | 10 | 18.2 | 3 | 12.5 | 0.744 |

Table 4. Effect of awareness about international guidelines and recommendations on practice in self-treatment and treatment of close relatives.

Discussion

Despite numerous medical guidelines discourage physicians to avoid self-treatment and treatment of friends and family members; it is well known fact that physicians frequently receive medical requests from close relatives, family members and friends.

The present study provides insight on different practices of self-treatment and treatment of close relatives among primary health care physicians in one of the largest provinces of Western region of Saudi Arabia. It also analyzed the sociocultural and psychological context under which physicians provide care for close relatives, including motivations, ethical perceptions, awareness and attitude.

Sampling was representative of the region as it covered all of the 5 sectors using two-staged stratified sampling. Characteristics of the population were marked by young age with relatively short professional experience as 3 out of 4 participants were aged below 40 years and had less than 10 years of practice. In addition, most of the participants were general practitioners (GPs) representing 61.3%, followed by family medicine doctors (25.0%). This imbalanced distribution may represent limitation of the study; however, it is consequent to the interview being scheduled during the days when most of the physicians were present in the center regardless of their specialty.

The major findings of this study are the remarkably high prevalence of practices including self-treatment, selfprescribing and a range of practices related to treatment of close relatives.

Self-care and self-prescribing are known to be highly prevalent practices among physicians regardless of the grade, specialty or center type, and may be justified by several factors [12-16]. Our study also demonstrated that there is no effect of gender, age or years of practice on the prevalence of self-treatment practice. A systematic review reported up to 99% of selftreatment among physicians and medical students [15]. Comparable observations are reported in other studies such as a nationwide prospective longitudinal study from Norway that showed 90% prevalence of self-prescribing among young physicians during their career and 54% during the previous year [17]. A Swiss study reported 90% prevalence of selfprescribing among primary care physicians including analgesics, antidepressants and tranquilizers, which were associated with high work-related stress [18]. Another study by Uallachain in 2007, showed that 92% of the GP trainees had self-prescribed and 35% referred themselves to a consultant, justifying such practice by a lack of time to care for themselves, as reported by 65% participants [19]. The same study reported that almost half of the physicians believe that they do not benefit from adequate healthcare, which is concordant with data from other studies [19,20]. Other studies suggest that self-prescribing among surgeons is less frequent [21], which could not be verified in our study due to sampling limitations. Self-prescribing of controlled substances was less common reported by only 7.5%, which is comparable with data from other studies and may simply reflect the frequency of such treatments in the general population [18,22].

The prevalence of self-care and self-prescribing practices remains generally high despite the non-negligible proportion of physicians who are formally registered with a doctor. According to studies, 21 to 100% of physicians are registered with another doctor [15,18,23,24], however, many prefer informal consultations with colleagues, family members or friends when they are ill [15,18]. Beyond all legal consideration, self-treatment practices in absence of regular care are associated with below-standard care which may reflect in poor treatment compliance, over-treating, frequent drug interactions or poor health outcomes such as low rates of cancer screening and vaccination [22,24]. On the other hand, the efficacy of legal solution regarding self-prescribing issue is controversial. An Australian research team advocated that restricting self-prescribing by means of legislation would have no effect in reducing the supposed risks and may engender adverse consequences [25].

Several barriers or factors were described in seeking formal healthcare help by physicians. Some of the factors include the doctor-being a professional him/herself, including embarrassment, lack of time, costs, personality trait of control and fear from loss of control, and unawareness about healthcare system or denial. Other factors related to provider or care system have been described such as confidentiality issues, poor quality of care stated by the doctor-patient, cultural tolerance regarding self-treatment, and over crowdedness of health centers [26]. Consequently, self-treatment is perceived as an advantage for the physician as it contributes to saving time, allows quicker relief, provides an experience and is costsaving [27].

In our study, family requests for care were found to be highly prevalence, reported by almost all participants (96.3%) as well as other practices including physical examination, diagnosis and medication prescription reported between 85.0% and 93.3% of the participants. However, similar to self-prescribing, prescribing controlled substances to close relatives was less common (16.3%). It is known that most physicians are confronted to care requests from family members at some point of their career [28,29].

Analysis of motivations to provide care for close relatives showed the important effect of the sociocultural context promoting sense of responsibility towards family members and priority they have to benefit from the individual’s material and moral commitment, including in our case the medical competencies of the physician’s relative [9]. Further analysis showed that participants felt more frequently comfortable providing care for their parents, spouses/husbands, siblings and children. These observation concords with the previously described cultural context, as these family members have a special place in the value system and benefit from direct right of obedience and support.

Similar to self-treatment, treatment of close relatives is subject to international recommendations and opinions, and is generally not advisable. Physicians are instead advised to encourage their relatives to formal care and “not undermine the confidence that their relatives have in their own GP by disparaging the advice and treatment that they are given” [6].

Two out of five participants declared having ever refused care for a close relative. The most common reason was to refer the patient to a more competent physician, which indicates a good level of conscientiousness among physicians regarding the limits of their own competences. This falls within general ethical recommendations in the Medical Ethics Manual issued by the World Medical Association (WMA), where it is stated that lack of competencies or specialization is a legitimate motivation to refuse care for a patient [30]. The other frequent reasons were related to respect of patient-intimacy, autonomy and confidentiality. These aspects may bias the noting the history of patient, physical examination and therapeutic decision. Other studies reported fear of guilt subsequent to misdiagnosis or mismanagement and prevention of noncompliance as important reasons advanced by physicians to refuse care for relatives [4,31]. Regardless of the ethical recommendations, refusing to treat family members because of such objective and professional reasons is acting according to basic morals of Medicine. The international Islamic Code of Medical and Health Ethics states that Islamic morality urges the physician to act by principle of justice and equity (Principle 3) and warns against all situations that could impede this principle [32].

Physicians’ perceptions about the different risks related to selftreatment and treatment of close relatives was average to high as per the specific risk. However, no statistically significant effect of risk perception on practice was found. However, such observation should not downplay the role awareness could have in awakening prudence of physicians and reducing exposure to such risks. On the other hand, despite the relatively adequate level of risk perception, practices of self-treatment and treatment of close relatives remained prevalent in the study population.

The present study showed a relatively a low rate of awareness about international ethical guidelines regarding self-treatment and treatment of close relatives, with less than one-third of the participants who declared being aware. However, awareness about international guidelines was not associated with practice, which may indicate that cultural background prevails on the ethical considerations, especially in the local context where no clear regulation of self-treatment and treatment of relatives exists [7,8]. On the other hand, approximately half of the interviewed physicians did not agree that self-treatment or treatment of close relatives should be inadvisable whereas almost one in five had no opinion. Several institutions such as the British Medical Association (BMA) emitted recommendations and opinion regarding self-treatment and treatment of close relatives and stated that it was not advisable as practice or should be restricted to urgent requests [6]. Similarly, both the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American College of Physicians (ACP) opined that physicians should not treat themselves or their close relatives and advanced a list of related circumstances that may impede physicians’ professionalism and efficiency or compromise the quality of care [4,5]. However, lack of promotion and monitoring of these guidelines resulted in insufficient compliance among doctors [13]. This indicates that in parallel with regulation, specific measures should be taken to optimize health care for physicians and facilitate access to occupational health [21].

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the reduced sample size due to low participation rate, which affected the statistical power of the study and compromised the validity and generalizability of the results. Further, reduced sample size prevented from exploring further statistical associations, such as effect of physician ’ s specialty on practice. Another parameter that would have been interesting to explore is motivations for self-treatment and barriers to formal care among physicians.

Nevertheless, this study provided for the first time in Saudi Arabia a descriptive and analytical picture of the practices related to self-treatment and treatment of close relatives among physicians working in public health centers. The observations provided raised several cultural and ethical questions as being the main components of the subject, in addition to a relative legal vacuum. Besides the previous parameters, any regulation project by authorities should consider in parallel with the implementation of occupational medicine with optimal services to ensure adherence to formal care and improve health outcomes among physicians. Further, national studies are warranted to explore other aspects of self-treatment and treatment of relatives including health, social and professional consequences, both on the physician and the patient.

Conclusion

Self-treatment and treatment of close relatives are highly prevalent among primary healthcare physicians in Western Saudi Arabia, practiced by 85% to 96% of the respondents regardless of their age, gender or specialty and comprises a high risk of inappropriate follow-up. Direct ascendants and descendants, spouses and siblings were the most frequently reported as being legitimate beneficiaries of care by the physicians. This reflects the socially prevailing value system of Saudi Arabia dictating absolute duty of obedience and support to these specific persons. Refusal of care to a relative was relatively rare and generally motivated by lack of competency and respect of patient ’ s privacy and intimacy. There is insufficient and imprecise awareness about international ethical opinions and recommendations regarding self-treatment and treatment of close relatives. This is in parallel with adequate perception about risks associated with these practices, however, both awareness and risk perception have no significant effect on physicians’ practice.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thanks Editage, a division of Cactus Communications for English language editing.

References

- Krall EJ. Doctors who doctor self, family, and colleagues. WMJ 2008; 107:279-284.

- Nik-Sherina H, Ng CJ. Doctors treating family members: A qualitative study among primary care practitioners in a teaching hospital in Malaysia. Asia Pacific J Fam Med 2006; 5: 1-6.

- College Of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. Physician treatment of self, family members, or others close to them. Policy Statement; 2016:1-7.

- Anyanwu EB, Abedi HO, Onohwakpor EA. Ethical issues in treating self and family members. Am J Public Health Res 2014; 2:99-102.

- Mossman D, Farrell HM, Gilday E. Should you prescribe medications for family and friends? Curr Psychiatr 2011; 10:41-43.

- Giroldi E, Freeth R, Hanssen M, Muris JWM, Kay M, Cals JWL. Family Physicians Managing Medical Requests From Family and Friends. Ann Fam Med 2018;16:45-51.

- The Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. Code of Ethics for Healthcare Practitioners. In: King Fahd National Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data 2014;1-52.

- Alahmad G, Al-Jumah M, Dierickx K. Review of national research ethics regulations and guidelines in Middle Eastern Arab countries. BMC Med Ethics 2012; 13:1-10.

- Gatrad AR, Sheikh A. Medical ethics and Islam: principles and practice. Arch Dis Child 2001; 84:72-75.

- Sedgwick P. Stratified cluster sampling. BMJ 2013; 347:7016.

- Montgomery AJ, Bradley C, Rochfort A, Panagopoulou E. A review of self-medication in physicians and medical students. Occup Med (Lond) 2011; 61:490-497.

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser JA. Palliative care professionals' care and compassion for self and others: a narrative review. Int J Palliat Nurs 2017; 23:219–229.

- Forsythe M, Calnan M, Wall B. Doctors as patients: postal survey examining consultants and general practitioners adherence to guidelines. BMJ 1999; 319:605-608.

- Shadbolt NE. Attitudes to healthcare and self-care among junior medical officers: a preliminary report. Med J Aust 2002; 177:S19-S20.

- Montgomery AJ, Bradley C, Rochfort A, Panagopoulou E. A review of self-medication in physicians and medical students. Occup Med (Lond) 2011; 61:490-497.

- Sawalha AF. A descriptive study of self-medication practices among Palestinian medical and nonmedical university students. Res Social Adm Pharm 2008; 4:164-172.

- Hem E, Stokke G, Tyssen R, Gronvold NT, Vaglum P, Ekeberg O. Self-prescribing among young Norwegian doctors: a nine-year follow-up study of a nationwide sample. BMC Med 2005; 3:1-7.

- Schneider M, Bouvier GM, Goehring C, Kunzi B, Bovier PA. Personal use of medical care and drugs among Swiss primary care physicians. Swiss Med Wkly 2007; 137:121-126.

- Uallachain GN. Attitudes towards self-health care: a survey of GP trainees. Ir Med J 2007; 100:489-491.

- Richards JG. The health and health practices of doctors and their families. N Z Med J 1999; 112:96-99.

- Chen JY, Tse EY, Lam TP, Li DK, Chao DV, Kwan CW. Doctors’ personal health care choices: a cross-sectional survey in a mixed public/private setting. BMC Public Health 2008; 8:1-7.

- El Ezz NF, Ez-Elarab HS. Knowledge, attitude and practice of medical students towards self medication at Ain Shams University, Egypt. J Prev Med Hyg 2011; 52:196-200.

- Mills J, Wand T, Fraser JA. Exploring the meaning and practice of self-care among palliative care nurses and doctors: a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:63.

- Gross CP, Mead LA, Ford DE, Klag MJ. Physician, heal Thyself? Regular source of care and use of preventive health services among physicians. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:3209-3214.

- Kay M, Del Mar CB, Mitchell G. Does legislation reduce harm to doctors who prescribe for themselves? Aust Fam Physician 2005; 34:94-96.

- Kay M, Mitchell G, Clavarino A, Doust J. Doctors as patients: a systematic review of doctors’ health access and the barriers they experience. Br J Gen Pract 2008; 58: 501-508.

- James H, Handu SS, Khaja KA, Sequeira RP. Influence of medical training on self-medication by students. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2008; 46:23-29.

- Balon R. Psychiatrist attitudes toward self-treatment of their own depression. Psychother Psychosom 2007; 76:306-310.

- Sanchez-Reilly S, Morrison LJ, Carey E, Bernacki R, O'Neill L, Kapo J, Periyakoil VS, deLima Thomas J. Caring for oneself to care for others: physicians and their self-care. J Support Oncol 2013; 11:75-81.

- Williams JR. Medical ethics manual. World Medical Association 2005.

- Scarff JR. Treating Family Members. Curr Psychiatr 2011; 10:25.

- World Health Organization, Others. Islamic code of medical and health ethics 2005.